Summary

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) students are more than four times as likely to attempt suicide compared to their straight and cisgender peers (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020). Negative treatment by others, such as bullying, is a strong and consistent risk factor for youth suicide (Koyanagi et al., 2019), and LGBTQ youth experience bullying at significantly greater rates than their straight and cisgender peers (Reisner et al., 2015; Webb et al., 2021). A recent study revealed that between 2011–2019, an average of 20% of U.S. high school students reported in-person bullying and 15% reported electronic bullying, with no significant changes in prevalence rates over time (Li et al., 2020). Affirming schools may be protective of suicide risk not only by providing direct identity support to LGBTQ youth but also by creating an environment where LGBTQ youth are less likely to experience bullying. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief explores bullying among LGBTQ middle and high school students including how experiences of bullying are associated with suicide risk and LGBTQ-affirming schools.

Results

The majority of LGBTQ youth (52%) who were enrolled in middle or high school reported being bullied either in person or electronically in the past year. One in three (33%) reported being bullied in-person (e.g., at school, on the way to school, at a party, or at work), while 42% were bullied electronically (e.g., online or via text message). Bullying was reported more often by LGBTQ middle school (65%) compared to high school students (49%). Transgender and nonbinary students (61%) reported higher rates of bullying compared to cisgender LGBQ students (45%). Those who were Native/Indigenous (70%), white (54%), and multiracial (54%) reported higher rates of being bullied compared to those who were Latinx (47%), Asian American/Pacific Islander (41%), or Black (41%).

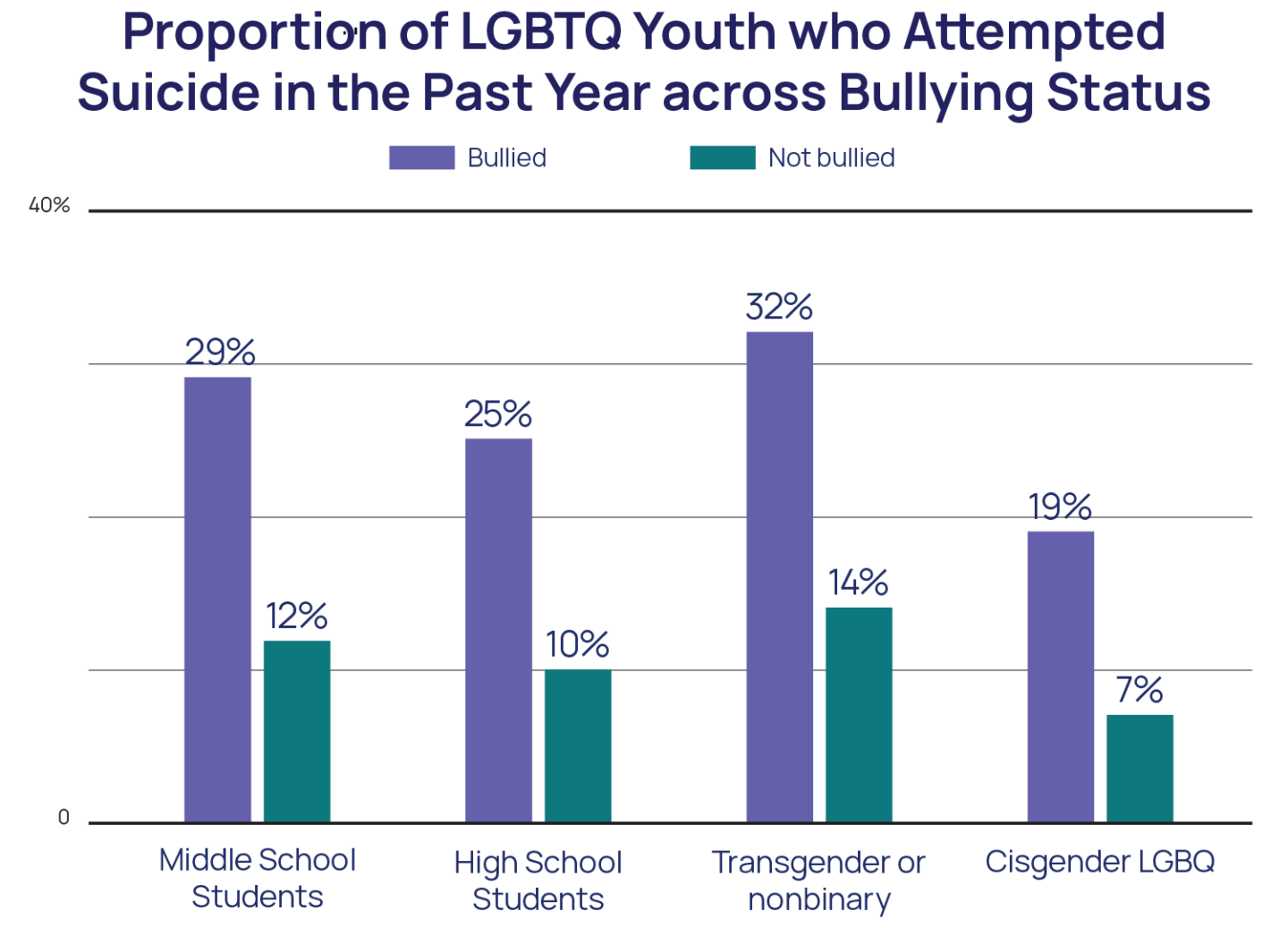

LGBTQ students who reported being bullied in the past year had three times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 3.06, p<.001). This finding was the same for both in-person and electronic bullying. Among LGBTQ middle school students, 29% of those who were bullied attempted suicide in the past year compared to 12% of those who were not bullied. Among high school students, 25% of those who were bullied attempted suicide in the past year compared to 10% of those who were not bullied. Across gender identity, 32% of transgender and nonbinary youth who were bullied attempted suicide compared to 14% who were not bullied, while 19% of cisgender LGBQ youth who were bullied attempted suicide compared to 7% who were not.

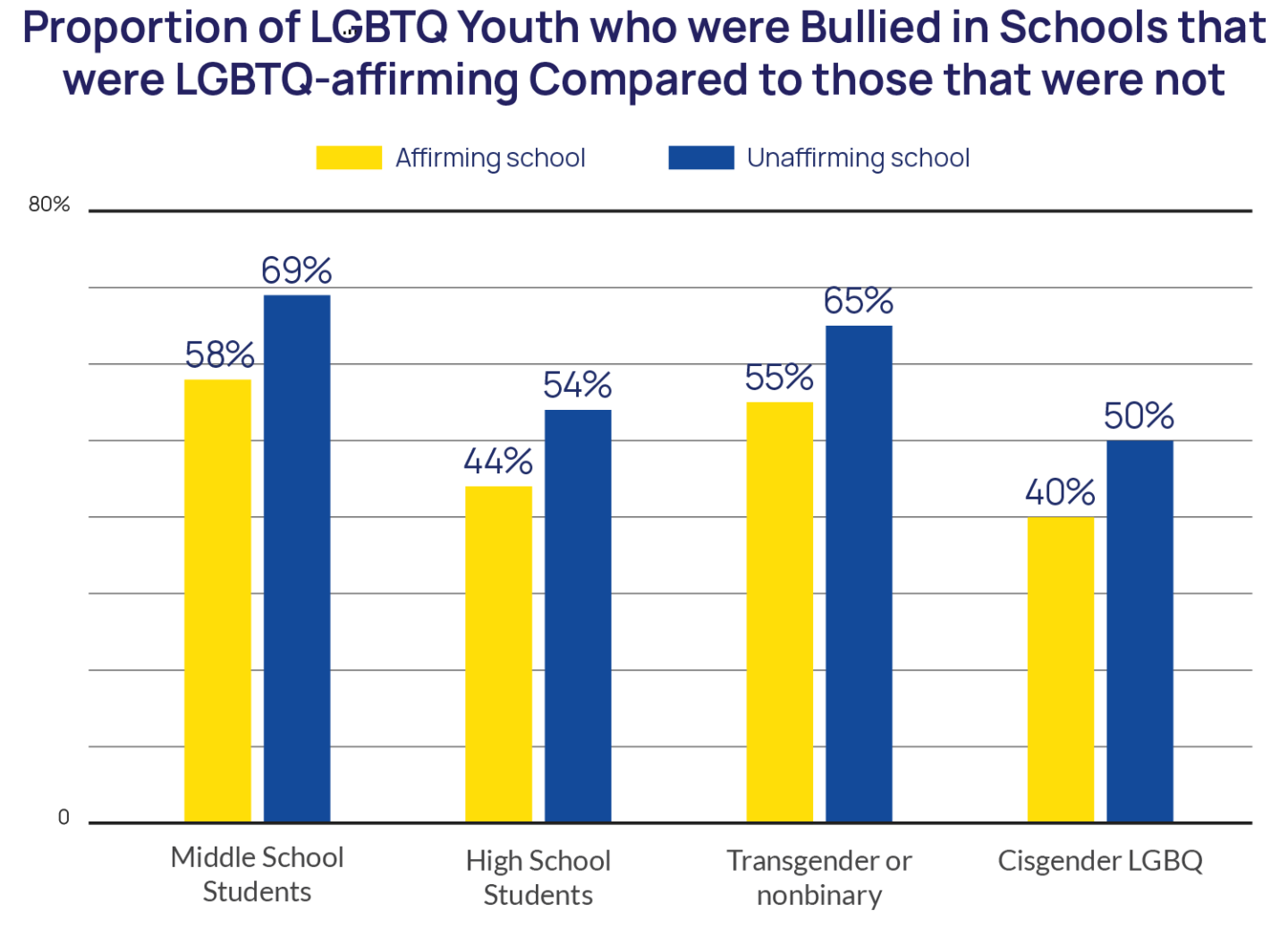

LGBTQ students who reported their school to be LGBTQ-affirming had 30% lower odds of being bullied in the past year (aOR = 0.69, p<.001). Overall, 46% of LGBTQ youth in LGBTQ-affirming schools report being bullied in the past year compared to 57% who did not report their school to be LGBTQ-affirming. Lower rates of having been bullied were found among both middle school (58%) and high school (44%) students who described their school as LGBTQ-affirming compared to middle school (69%) and high school (54%) students who did not. Transgender and nonbinary youth in schools that were LGBTQ-affirming reported lower rates of being bullied (55%) compared to those in schools that weren’t LGBTQ-affirming (65%), as did cisgender youth (40% vs. 50%).

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between October and December of 2020 of 34,759 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. These analyses included 13,536 youth who were enrolled in middle or high school at the time of survey completion and provided answers to questions about bullying and suicide risk. Our items on attempted suicide and bullying were based on measures used in the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey. We assessed past-year suicide attempts using the question, “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” with responses coded as either “none” or “one or more times.” In-person bullying was examined with the question, “During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied by someone in person? This is when someone is doing it face-to-face, like to and from school, at school, at a party, or at work.” Electronic bullying was examined using the question, “During the past 12 months, have you been electronically bullied? Count being bullied through texting, Instagram, Facebook, or other social media.” Youth who responded “yes” to either of these items were considered to have experienced bullying in the past year. LGBTQ middle and high school students were also asked whether or not their school was an LGBTQ-affirming space. Adjusted odds logistic regression models were used to predict the odds of experiencing bullying and the relationship between LGBTQ-affirming schools and bullying after adjusting for school type, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and sexual identity. An additional logistic regression model was conducted to examine the association between being bullied and attempting suicide in the past year after adjusting for school type, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and sexual identity.

Looking Ahead

These findings indicate that bullying of LGBTQ youth remains a significant area of concern, particularly among middle school students, students who are transgender or nonbinary, and Native/Indigenous students. Our data pointed to rates of electronic bullying that exceeded those of in-person bullying. Notably, these data were collected during a time when many students spent at least a portion of the prior year outside of physical school walls due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research underscores the dire need for increased investment in both bullying and suicide prevention initiatives that explicitly have protections for LGBTQ youth.

Previous research has found states with anti-bullying laws that specifically consider sexual orientation to be associated with lower odds of student suicide attempts compared to states with anti-bullying laws that do not mention LGBTQ identities (Meyer et al., 2019). Our findings here indicate the bullying is lower in schools that are described as LGBTQ-affirming, and our previous findings indicate that LGBTQ-affirming schools are associated with significantly lower odds of a past-year suicide attempt. Schools can become more affirming of their LGBTQ students in a variety of ways, including establishing Gender and Sexuality Alliances (GSAs), creating policies and norms around sharing names and pronouns, including LGBTQ issues in curricula, and providing LGBTQ cultural competence training for all teachers and staff. By creating environments that are caring, accepting, and supportive of all students, school leaders and staff may be able to both directly impact the well-being of marginalized students and cultivate a peer culture that values and accepts all identities.

The Trevor Project firmly believes that youth should be protected from bullying and have access to environments where they are supported in their identities. Our Crisis Services team works 24/7 to be available for LGBTQ youth in crisis, including those who may be experiencing bullying. Our Advocacy team focuses on policy solutions to creating LGBTQ-affirming and inclusive environments, including in school settings. Our Public Education team is also committed to reducing bullying by providing trainings on LGBTQ allyship and suicide prevention to key stakeholders across the U.S.

| References Johns, M.M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L.C., Zewditu, D., McManus, T., et al. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school student–19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 65-71. Johns MM, Lowry R, Haderxhanaj LT, et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly, 69(Suppl-1):19–27. Koyanagi, A., Oh, H., Carvalho, A. F., Smith, L., Haro, J. M., Vancampfort, D., … & DeVylder, J. E. (2019). Bullying victimization and suicide attempt among adolescents aged 12–15 years from 48 countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(9), 907-918 Li, R., Lian, Q., Su, Q., Li, L., Xie, M., & Hu, J. (2020). Trends and sex disparities in school bullying victimization among US youth, 2011–2019. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1-6. Meyer, I. H., Luo, F., Wilson, B. D., & Stone, D. M. (2019). Sexual orientation enumeration in state antibullying statutes in the United States: Associations with bullying, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts among youth. LGBT Health, 6(1), 9-14. Reisner, S. L., Greytak, E. A., Parsons, J. T., & Ybarra, M. L. (2015). Gender minority social stress in adolescence: disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(3), 243-256. Webb, L., Clary, L. K., Johnson, R. M., & Mendelson, T. (2021). Electronic and school bullying victimization by race/ethnicity and sexual minority status in a nationally representative adolescent sample. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(2), 378-384. |

For more information please contact: [email protected]