EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

There is minimal research specifically exploring Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) mental health and well-being. Even less explores the intersection of AAPI and LGBTQ identities, particularly among youth. AAPI LGBTQ youth’s identification with multiple marginalized identities might make them more susceptible to negative experiences, and as a result, poorer mental health and well-being. This report is one of the first to explore the mental health and well-being of LGBTQ youth who are AAPI and provide findings specific to six major AAPI origin groups. It uses data from a national sample of nearly 3,600 AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who participated in The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health.

AAPI LGBTQ youth in our sample represent a vast and diverse community.

- 27% of our sample of AAPI LGBTQ youth were Chinese, 21% Filipino, 15% Japanese, 14% Indian, 12% Korean, 9% Vietnamese, and 3% each Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, Taiwanese, and Thai

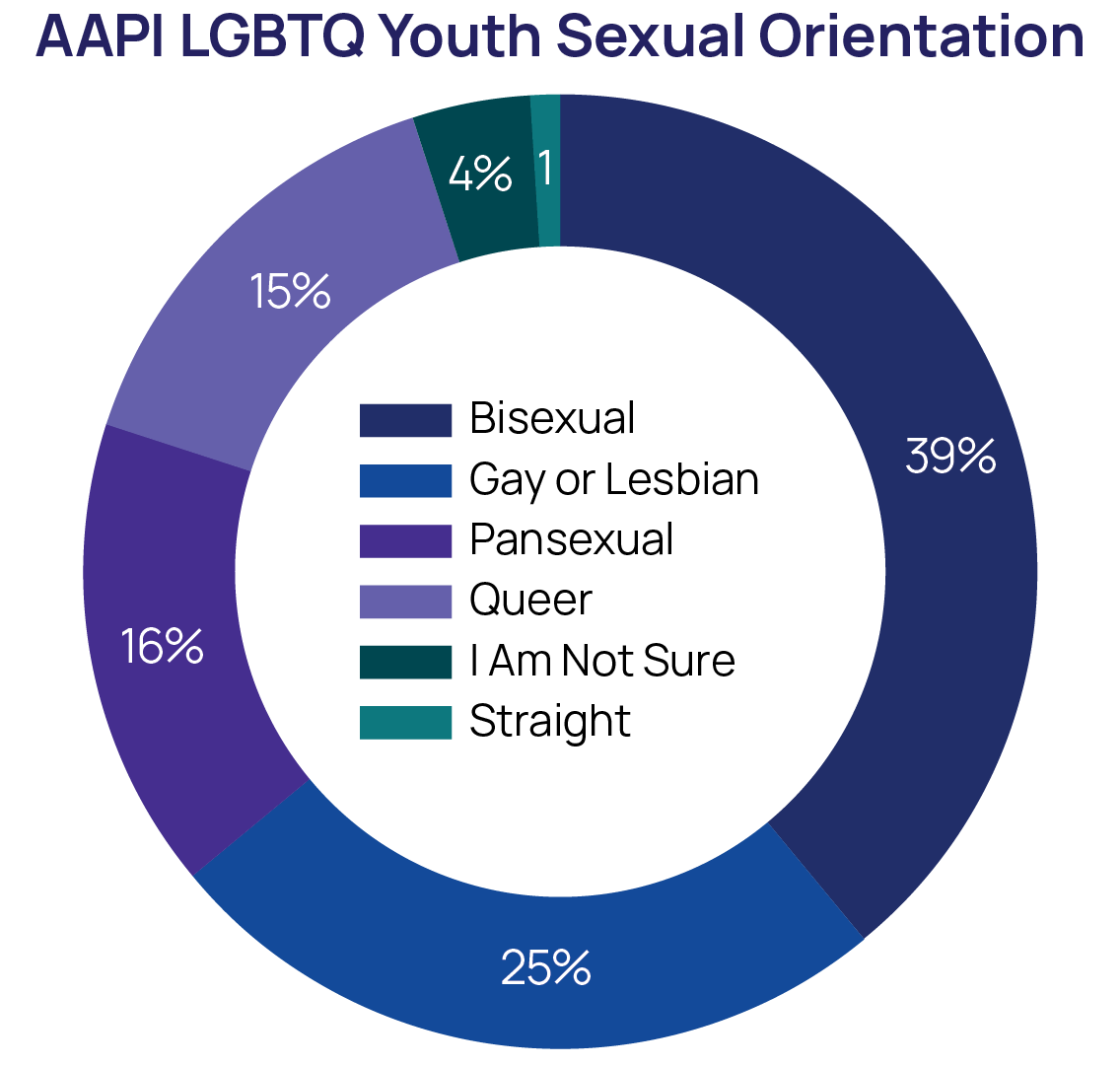

- 39% of AAPI LGBTQ youth identified as bisexual, 25% as gay or lesbian, 16% as pansexual, and 14% as queer

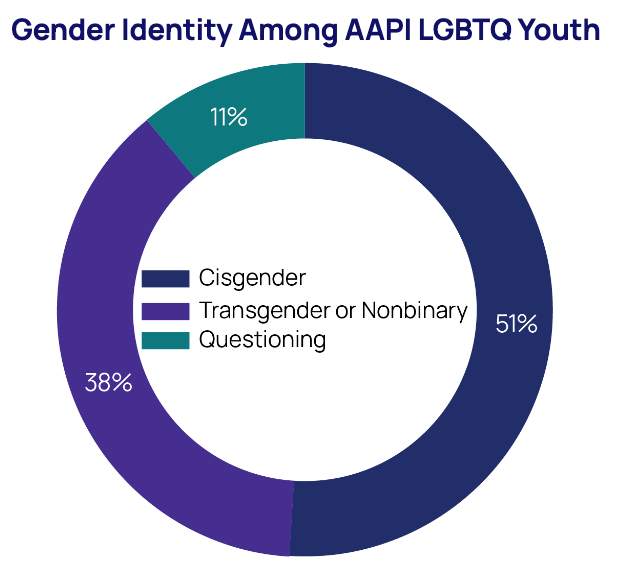

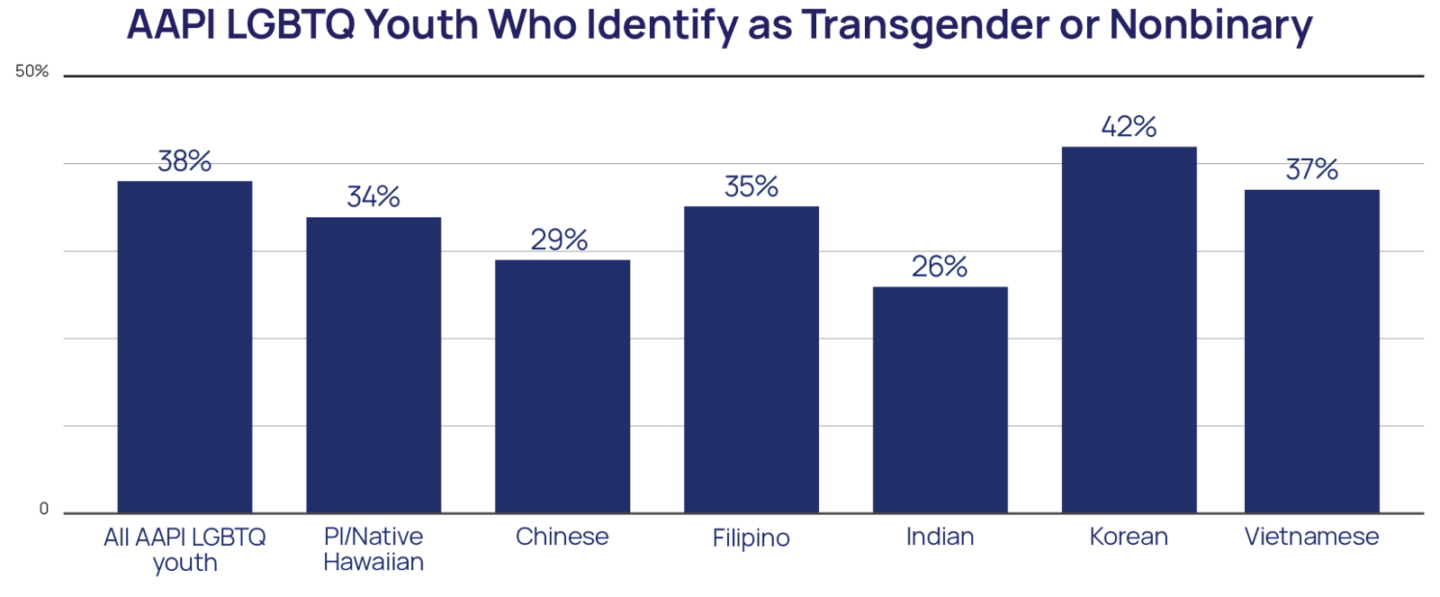

- 38% of AAPI LGBTQ youth identified as transgender or nonbinary, including 42% of Korean LGBTQ youth

- 15% of AAPI LGBTQ youth were born outside of the U.S., with 20% speaking a language other than English at home including Cantonese, Hindi, Bengali, and Japanese

AAPI LGBTQ youth are just as vulnerable to mental health challenges as other LGBTQ youth.

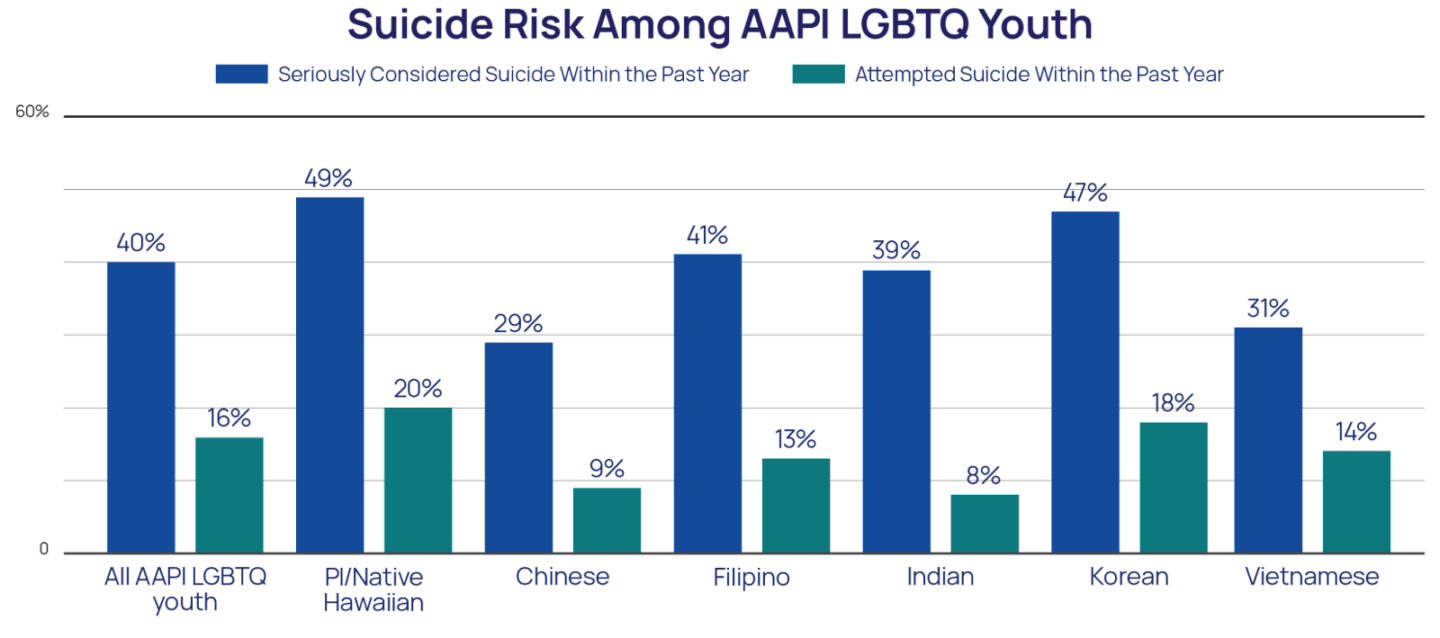

- 40% of AAPI LGBTQ youth seriously considered suicide in the past year, including 50% of AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth and 49% of Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth

- 16% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported a suicide attempt in the past year, including 21% of AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth and 20% of Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth

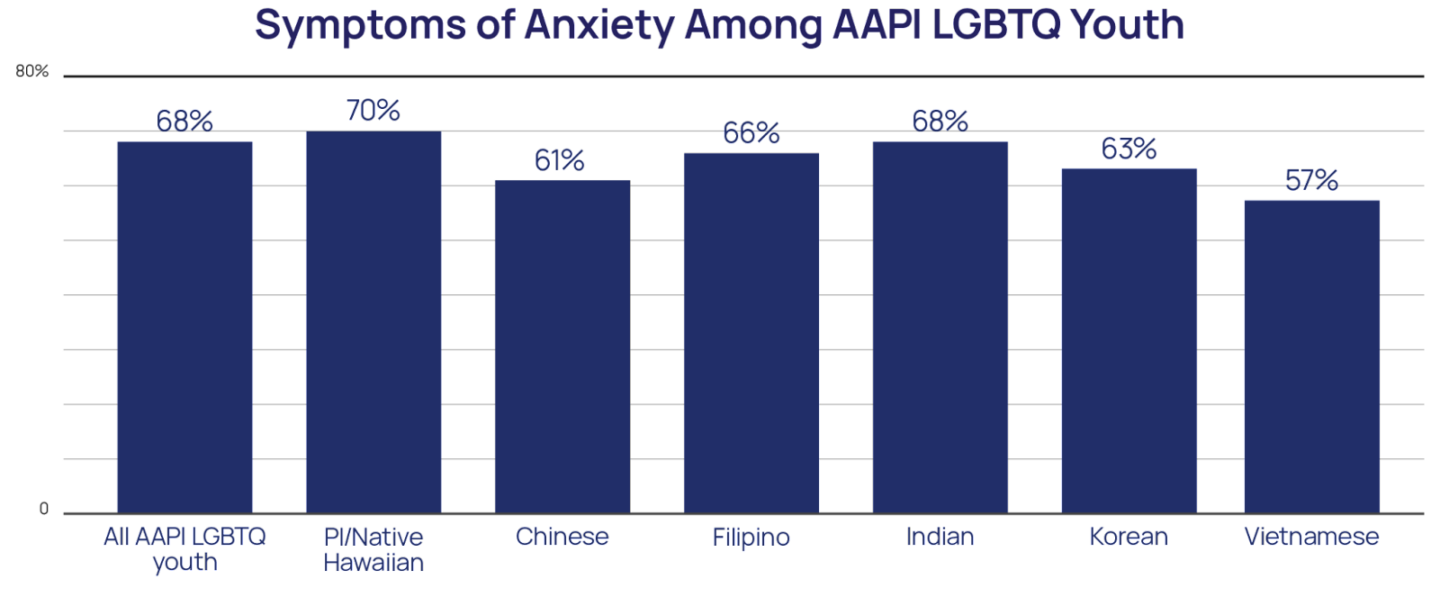

- 68% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in the past two weeks

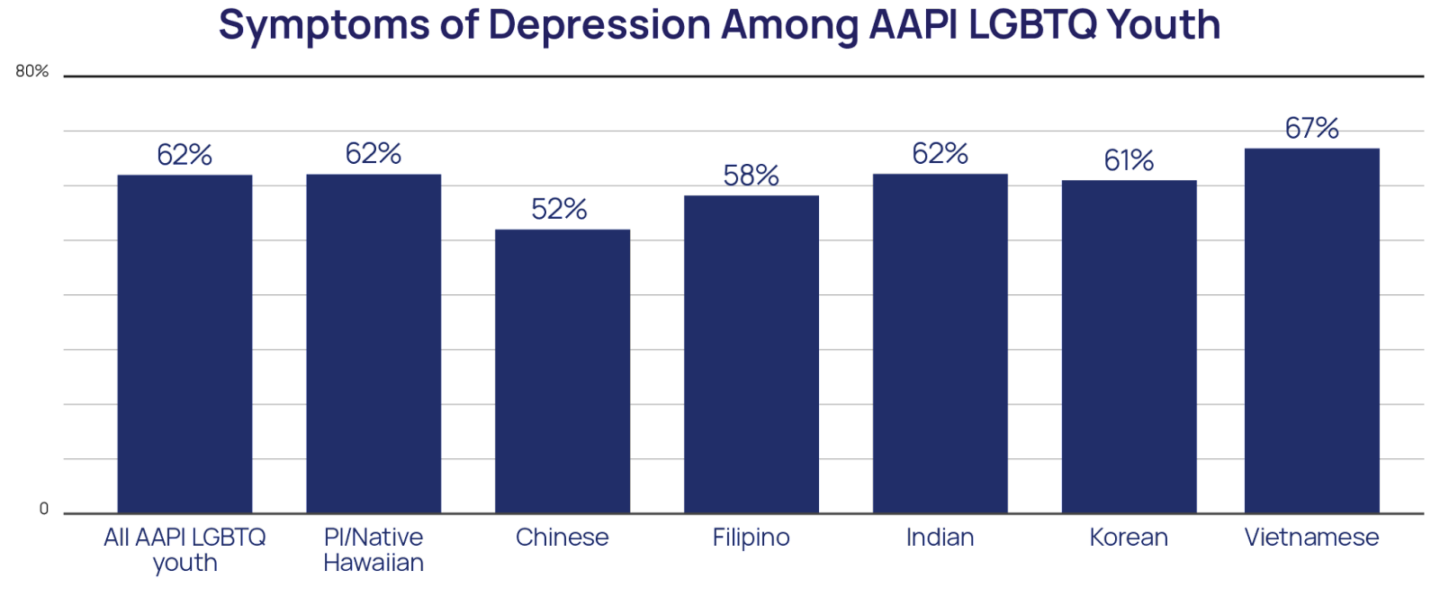

- 61% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported symptoms of major depressive disorder in the past two weeks

AAPI LGBTQ youth experience a variety of both similar and unique risks for suicide compared to other LGBTQ youth.

- More than half (55%) of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported that someone attempted to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity

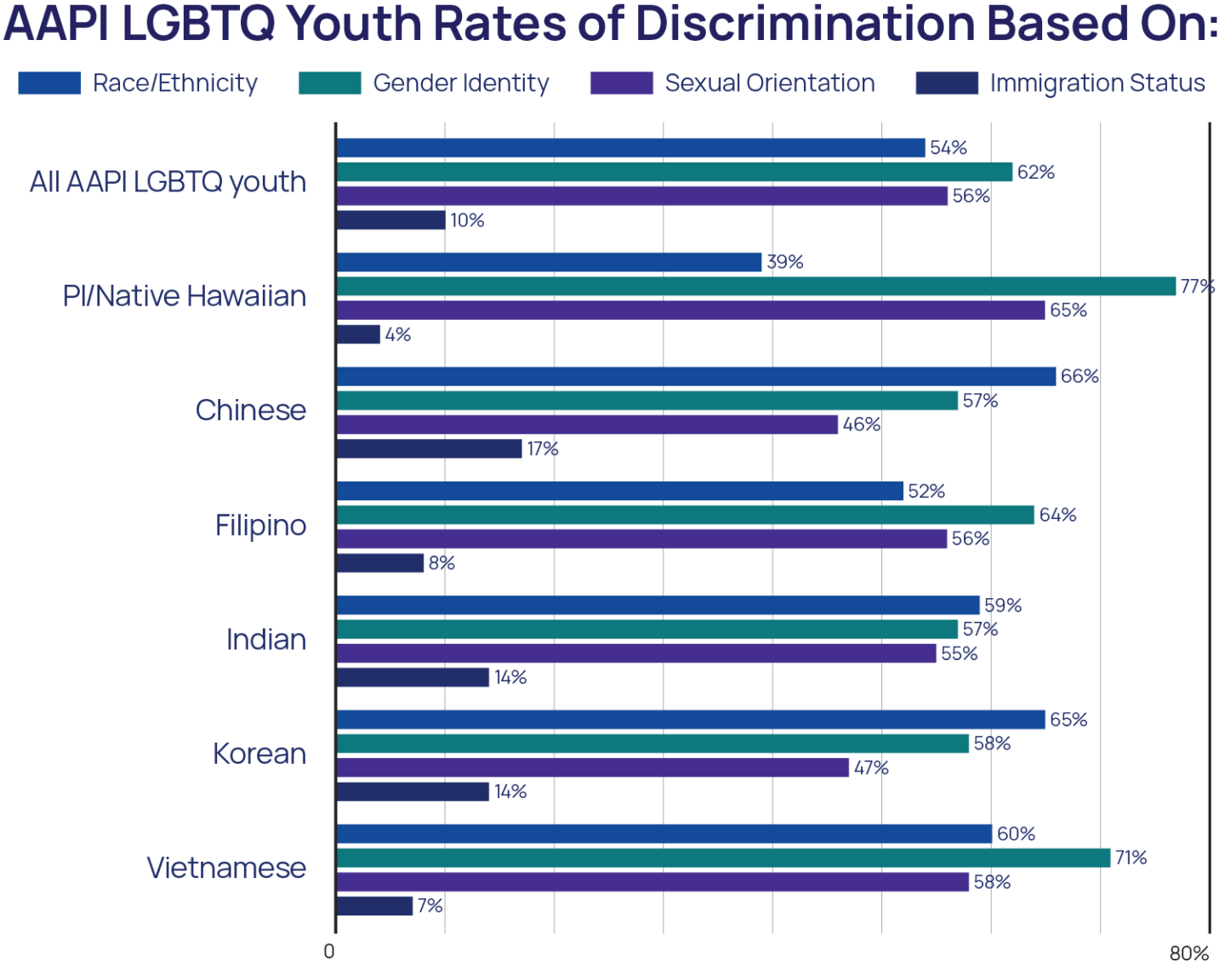

- 54% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported discrimination based on their race/ethnicity in the past year

- 63% of AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth reported discrimination based on their gender identity

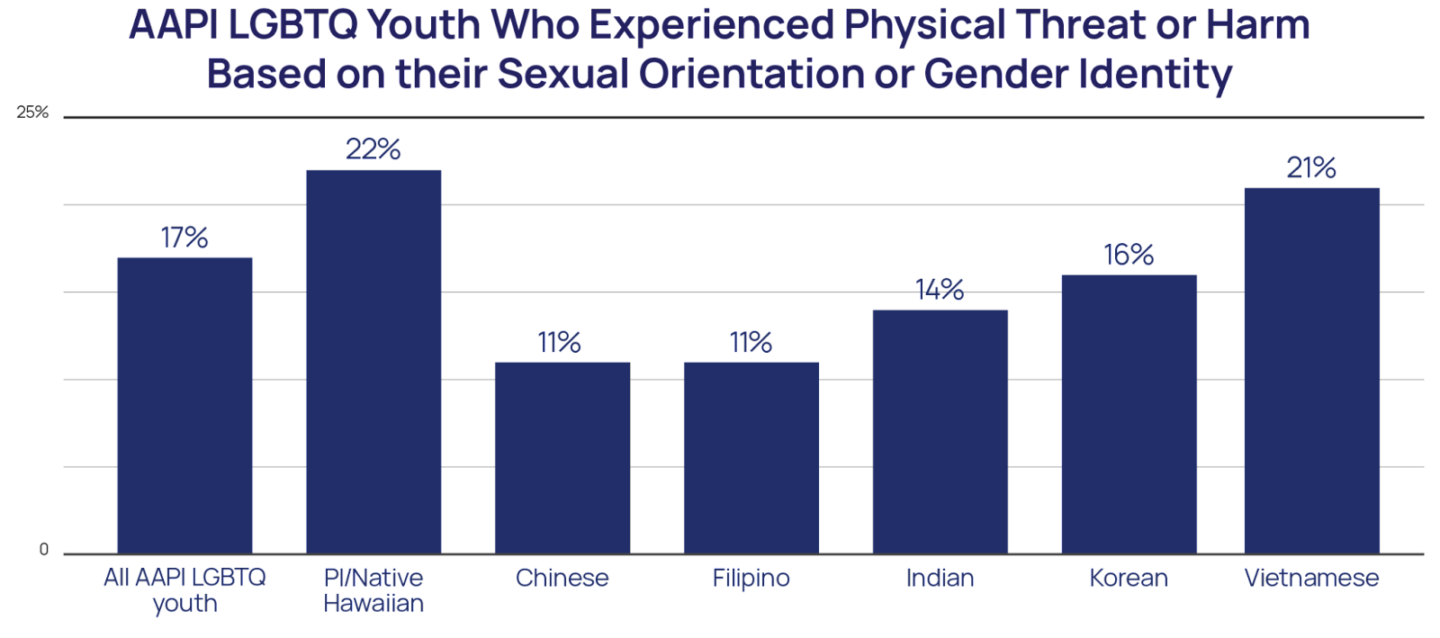

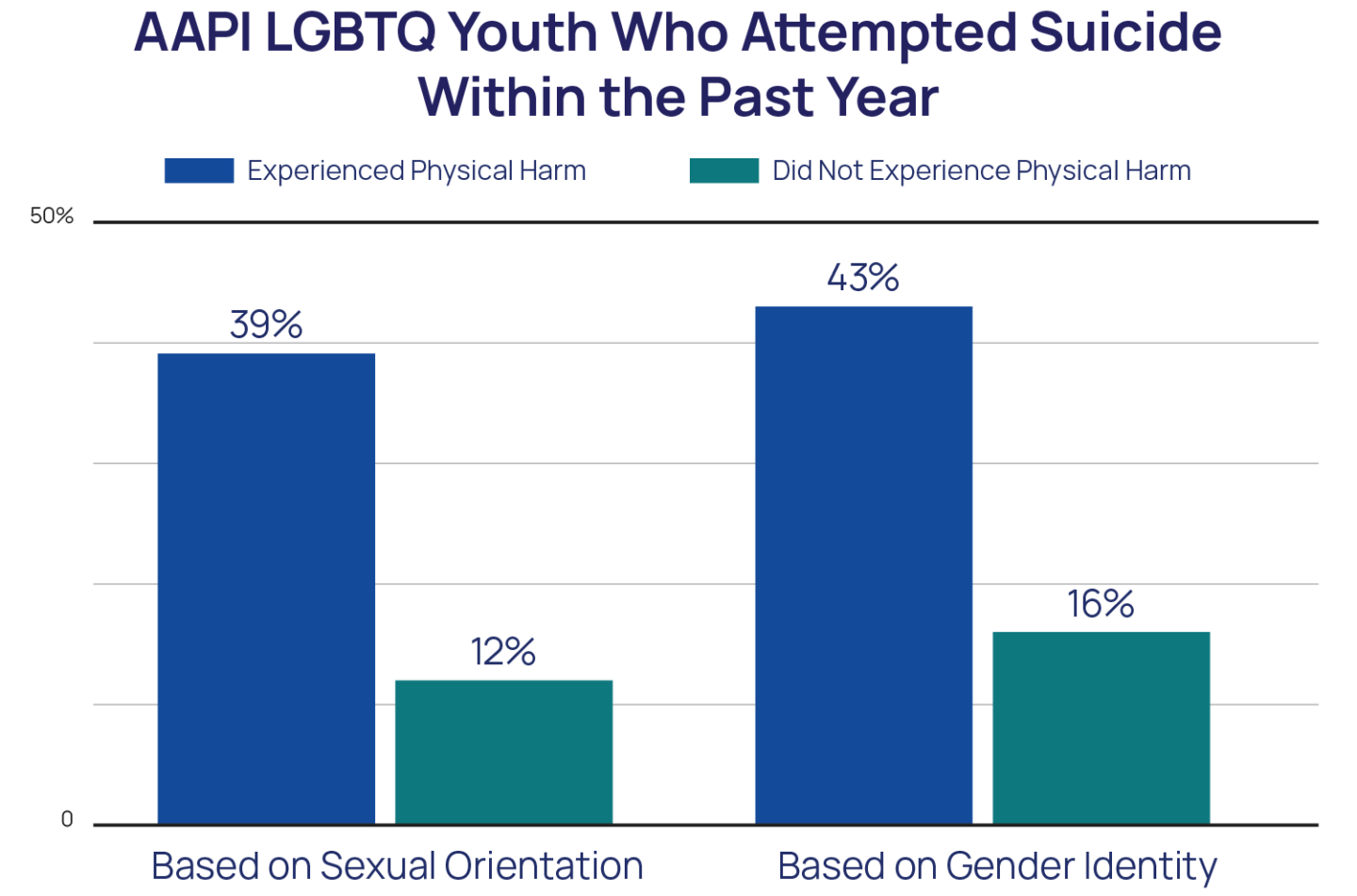

- 17% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported that they had been physically threatened or harmed due to their LGBTQ identity in the past year

- 10% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported discrimination based on their immigration status

There are also many protective factors for AAPI LGBTQ youth suicide.

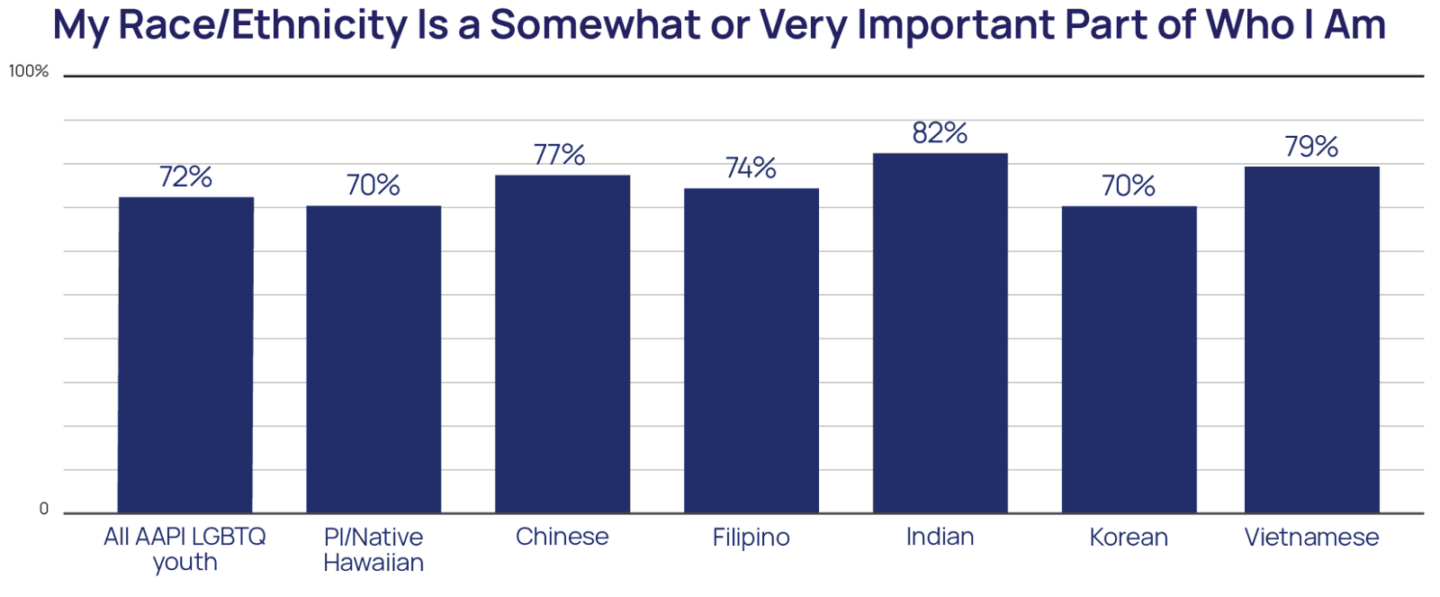

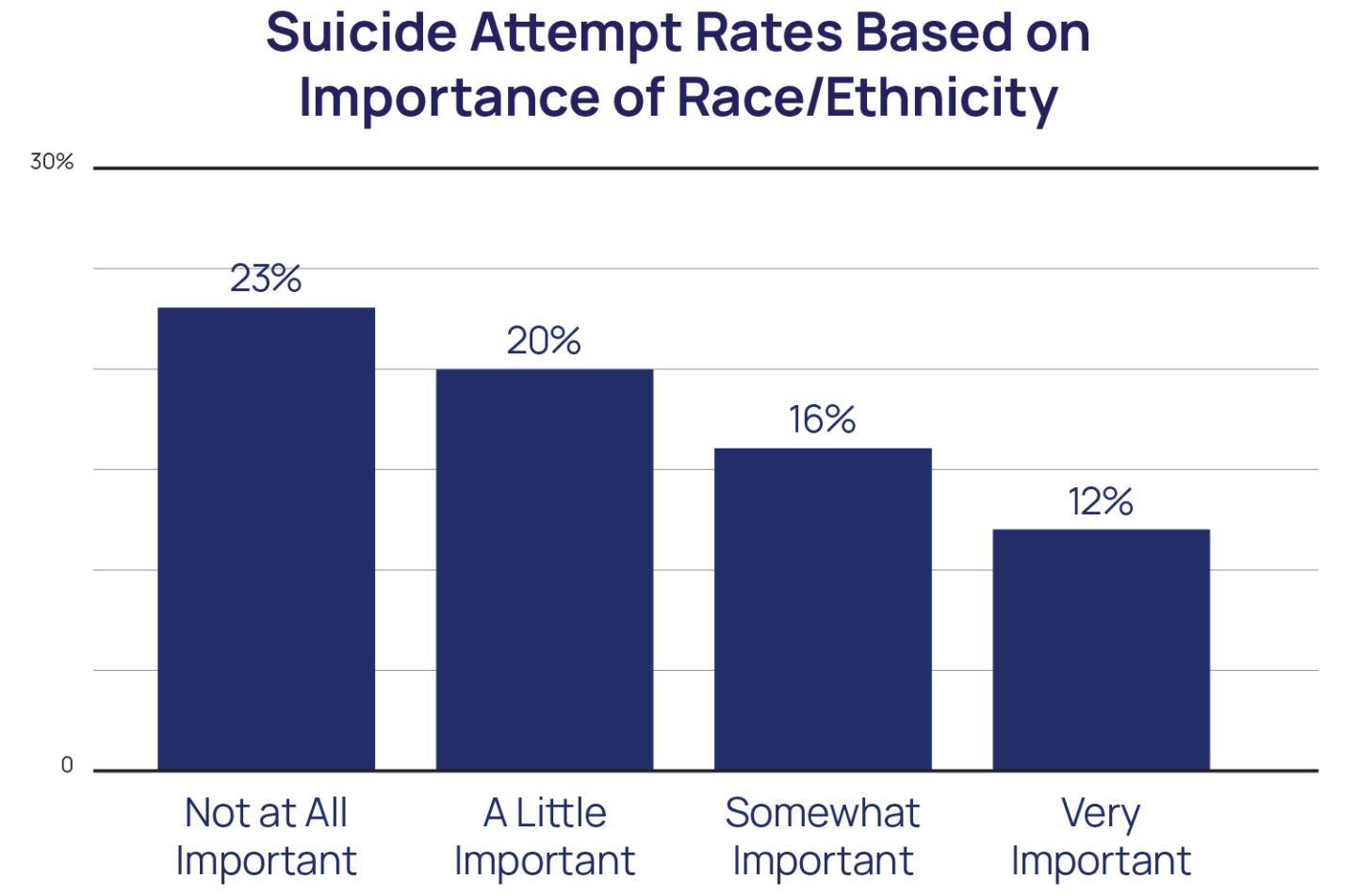

- Feeling that race/ethnicity was important to who they are was a protective factor for AAPI LGBTQ youth

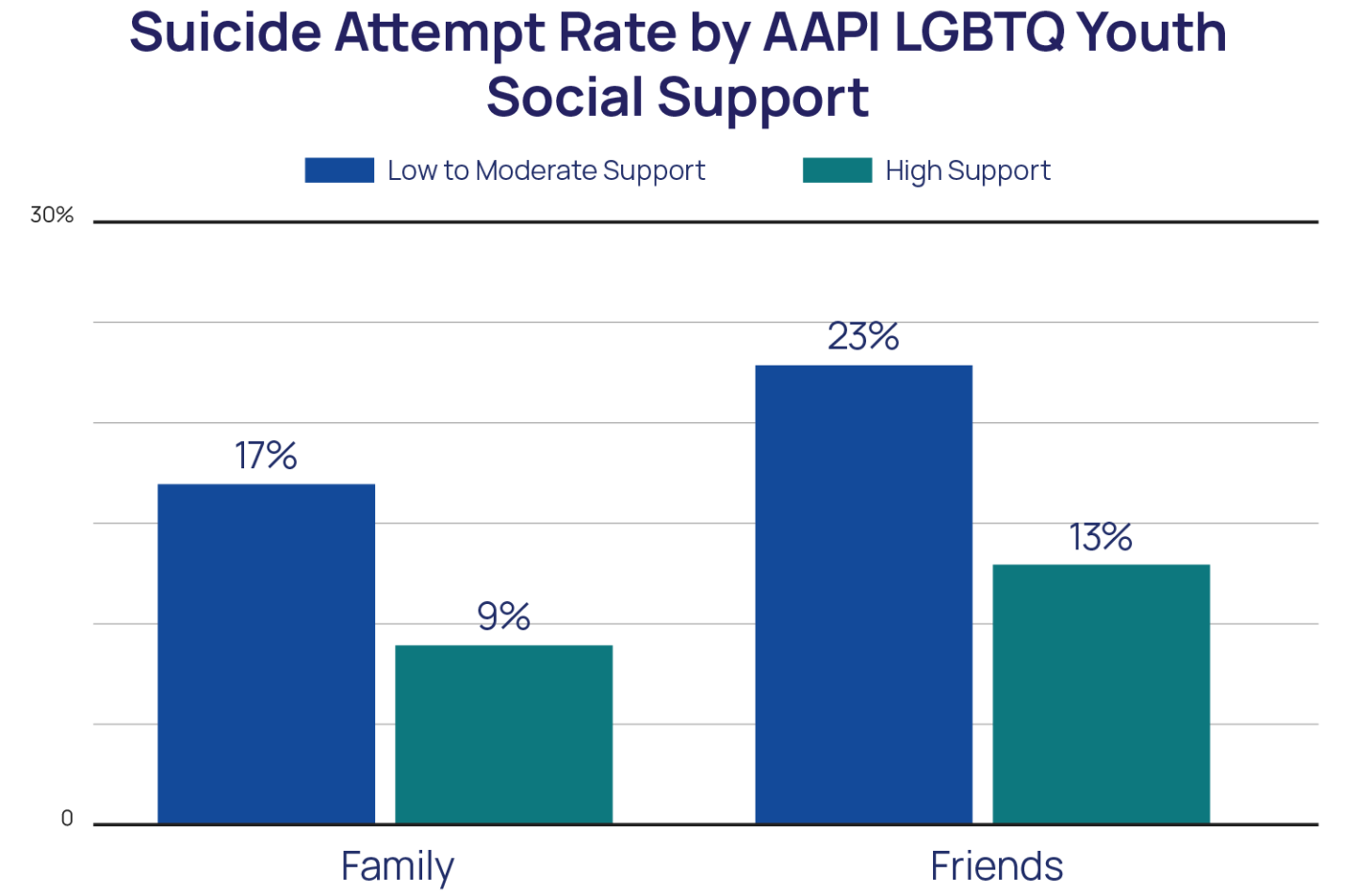

- AAPI LGBTQ youth who have social support from friends attempted suicide at lower rates compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth without this support

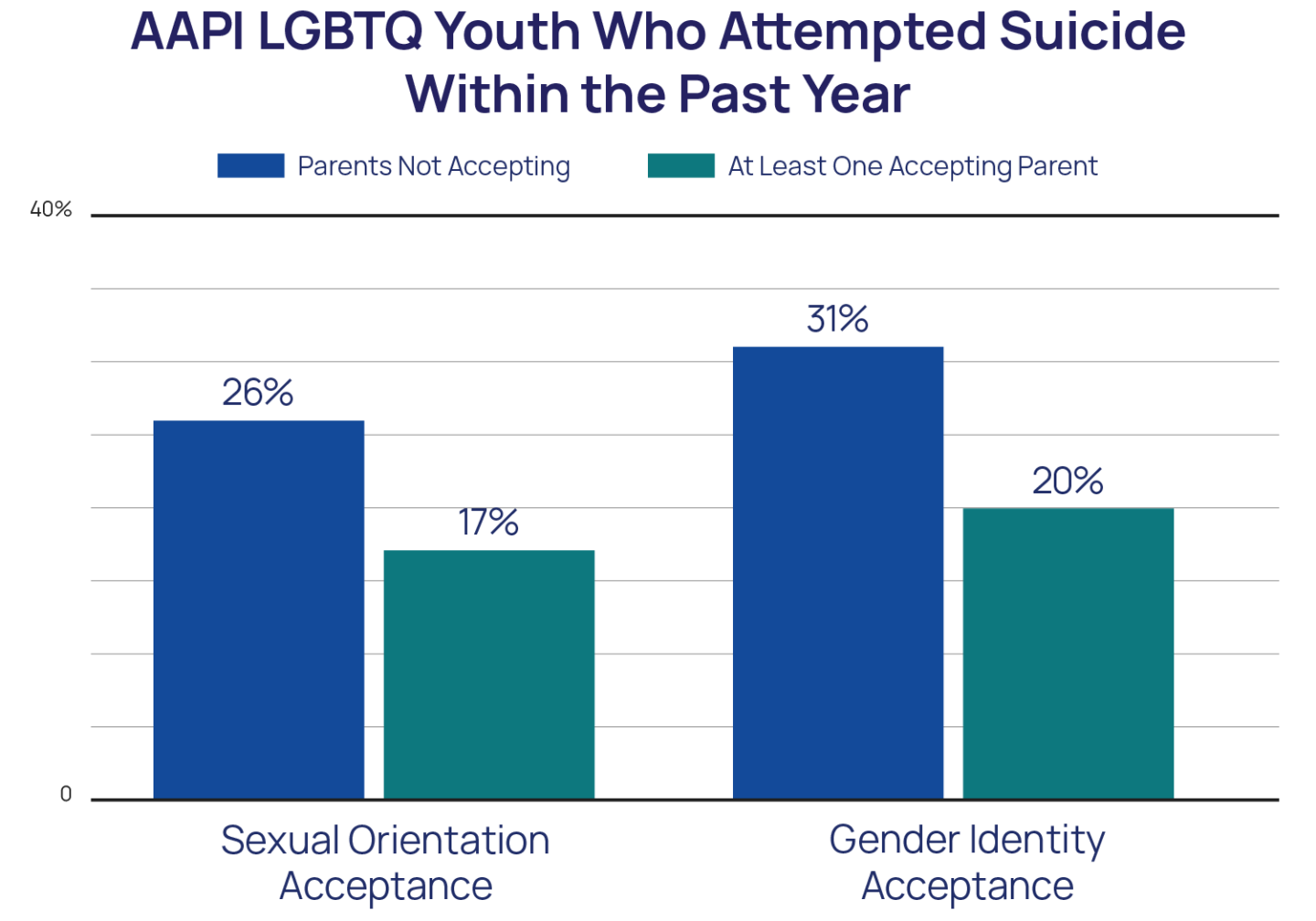

- Parental acceptance of their sexual orientation or gender identity was a protective factor for AAPI LGBTQ youth suicide

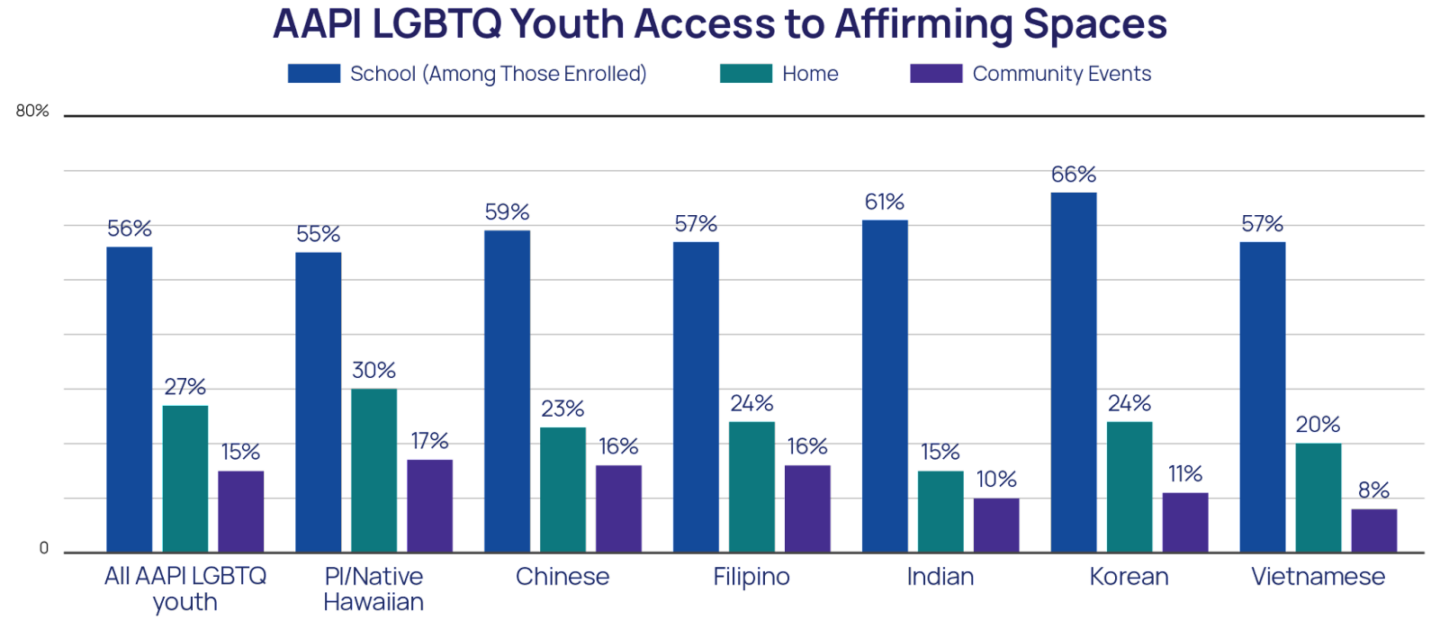

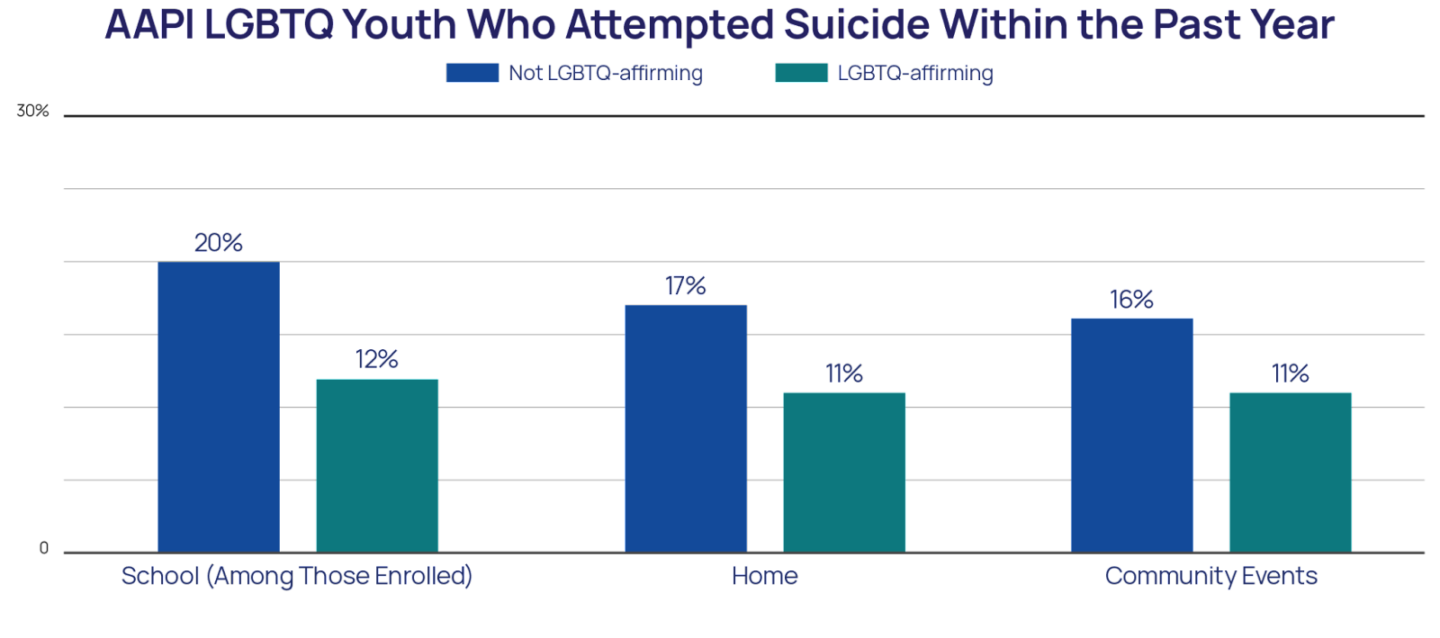

- AAPI LGBTQ youth who had access to LGBTQ-affirming spaces attempted suicide at lower rates compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth without access to such spaces

Methodology Summary

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data using an online survey platform between October and December 2020. An analytic sample of nearly 35,000 youth ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. All youth were asked, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, more than one race or ethnicity, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, White/Caucasian, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Youth who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question where they were able to select with which races or ethnicities they identified. The current analyses include the 3,594 LGBTQ youth who either identified as exclusively Asian/Asian American or Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian or who identified as multiracial Asian/Asian American or Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, henceforth just referred to as AAPI unless otherwise specified. We use the acronym AAPI in this report because these were the identities selected by the youth themselves on the survey.

Recommendations

AAPI youth report rates of mental health challenges that are comparable to the overall LGBTQ youth population, or even higher for some specific ethnicities. These youth face risk factors that are not only similar to all LGBTQ youth, such as anti-LGBTQ victimization, but also those that are unique to their experience as AAPI individuals in the U.S., such as immigration-based discrimination. Greater resources are needed to specifically address AAPI LGBTQ youth and their unique needs in both research and suicide prevention efforts — this includes gaining more insights into interethnic differences to better inform practices. Given the importance and protectiveness of both cultural and familial connections for AAPI youth, efforts aimed at suicide prevention for LGBTQ youth must be culturally salient for AAPI LGBTQ youth and address the specific issues they are facing. This could include providing support to local AAPI-based organizations and religious entities that already have the infrastructure and community trust to help support AAPI LGBTQ youth and their families.

BACKGROUND

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth face disparities in poor mental health compared to their straight and cisgender peers. LGBTQ youth report higher rates of anxiety and depression and are also more likely to engage in self-harm, seriously consider suicide, and attempt suicide compared to straight, cisgender youth (Johns et al., 2020). This increased risk is not due to being LGBTQ in and of itself but is instead due to chronic stress stemming from the marginalized social status that LGBTQ individuals have in society (Meyer, 2003). LGBTQ youth often face challenges such as higher rates of rejection, victimization, bullying, and discrimination, among others (Kosciw et al., 2018) which can then lead to internalized homophobia and perceived burdensomeness (Baams et al., 2015). Research also finds that transgender and nonbinary youth specifically report rates of poor mental health outcomes that are not only higher than cisgender youth (Johns et al., 2019) but higher when compared to cisgender LGBQ youth as well (Price-Feeney et al., 2020). However, important differences exist among LGBTQ youth, particularly among LGBTQ youth who hold multiple identities, such as also being Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI), which can increase their risk for poor mental health.

AAPI people in the United States have unique experiences and challenges that may place AAPI LGBTQ youth at increased risk for poor mental health. AAPIs are the fastest-growing major racial or ethnic group in the United States with more than 22 million Asians and 1.4 million Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiians living in the U.S. (United States Census Bureau, 2019; Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). However, AAPI Americans continue to face invisibility, isolation, discrimination, bullying, and harmful stereotypes (Jeung et al., 2020). Historically, AAPI people in the U.S. have experienced widespread discrimination, even as a result of official government policy, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Additionally, some AAPI nations were past or are current American colonies, which has reshaped political and cultural environments (Alvarez et al., 2020). Furthermore, AAPI people are often subjected to microaggressions in which others communicate that AAPI people are foreigners in their own land, make ascription of intelligence, exoticize Asian women, invalidate interethnic differences, deny racial realities, pathologize cultural values or communication styles, view AAPI individuals as second-class citizens, and fail to see and recognize them (Sue et al., 2009). The view that AAPI Americans are perpetual foreigners is reflected in AAPI youths’ experiences with bullying through mocking their names, languages, and accents (Chou & Feagin, 2008). AAPI Americans are also subjected to the “model minority” myth—or the perception of universal success among AAPIs—which does not allow for diversity among AAPIs, creates pressure for academic success for AAPI youth, forces AAPI people to conform to a specific behavioral standard, and, when internalized, may be performed as a coping strategy for racism, all of which creates internal pressure that can impact mental health (Park, 2011; Lee et al., 2009). With an estimated 71% of AAPI adults born in another country (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021), many AAPI youth are living with parents who immigrated to the U.S. and may experience stress associated with balancing dual cultures, having differing levels of acculturation, and with also not wanting to disappoint parents who made sacrifices for them (Lee et al., 2009; Crane et al., 2005). More recently, AAPI Americans have increasingly become the targets of violence and discrimination related to anti-Asian sentiments connected to the COVID-19 pandemic, with reports showing a 77% increase in anti-Asian hate crimes from 2019 to 2020 (United States Department of Justice, 2021) and one in five AAPI Americans reporting a hate incident in 2021 (Stop AAPI Hate, 2021). Finally, there are risks present within the AAPI community as well. For example, while tempering strong displays of emotions may be adaptive for promoting family cohesiveness in AAPI families, the suppression of verbal praise and of negative emotions may be risk factors for lowered confidence in abilities (Stevenson & Stigler, 1992) and anxiety or depression (Wei et al., 2004). It is important to note that the category of AAPI is inclusive of individuals from many different countries who have a variety of cultural practices and experiences within the U.S. For example, South Asian students and those perceived to be Muslim are often targets of Islamophobia (Abu El-Haj, 2015) and while some AAPI individuals may benefit from the model minority myth, some Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are not afforded the opportunity to approximate Whiteness and the privileges that come with it (Reyes, 2007). As such, the diverse experiences within AAPI communities might lead to different mental health outcomes (Esperat et al., 2004).

The stressors experienced at the intersection of an AAPI identity and an LGBTQ identity might increase the risk for poor mental health challenges. From an intersectional perspective, a person’s position or social location in society, based on social demographics such as race, gender, class, sexual orientation, among others, affords unique experiences, particularly for people with multiple marginalized identities (Collins & Bilge, 2020). For AAPI LGBTQ youth, this suggests that their identities, LGBTQ and race/ethnicity, among others, shape their lived experiences such that they are different from other LGBTQ youth and also from other AAPI youth. The little research that exists exploring the intersection of these two identities suggests that Asian LGBTQ adults often lose their ties to their ethnic communities due to homophobia or a general lack of understanding of their identities, and while they might be able to gain support and connection from the LGBTQ community, they often find racism and xenophobia in these spaces (Nakamura et al., 2013). For example, AAPI LGBTQ people report experiencing homophobia and transphobia within the AAPI community and also experiencing racism from the LGBTQ community (Dang & Hu, 2004). AAPI LGBTQ youth report specific challenges navigating social norms, accessing affirming spaces, and experiencing a variety of environmental stressors, including family rejection and bullying, and assault (HRC, 2019; Truong et al., 2020). Furthermore, AAPI youth may also feel that being LGBTQ might be a disappointment to their parents and experience internalized stigma and shame as a result (Yeh & Huang, 1996).

A strong connection to culture and family may serve to buffer the impact of the challenges faced by AAPI LGBTQ youth. While being both AAPI and LGBTQ may place AAPI LGBTQ youth at risk, there may also be some protectiveness in having dual identities. Research suggests that the ability to draw on multiple identities, and shift these identities to one that is more adaptive to a particular situation without fully de-identifying with any, might be protective (Pittensky et al., 1999). AAPI families, in particular, often provide protection and diminish risk associated with discriminatory experiences and other challenges through the promotion of family interdependence, collectivism, and obligation (Hofstede, 1980; Yee et al., 2007). This suggests that AAPI LGBTQ youth may benefit from close familial relationships if they can be supported in their identities. It further suggests that a strong cultural connection, and the ability to draw on cultural strengths of interconnectedness and support, may also be protective for LGBTQ youth.

Research has largely failed to consider the mental health and well-being of AAPI LGBTQ youth and how they might be impacted by various risk and protective factors. Often citing sample size, quantitative research on the experiences of LGBTQ youth frequently fails to explore the specific experiences of AAPI youth. Furthermore, research on AAPI youth often does not consider how sexual orientation and gender identity may influence their findings, leaving AAPI LGBTQ youth’s mental health largely unaddressed in research. Therefore, little is known about AAPI LGBTQ youth, let alone mental health and well-being, and as such, their specific needs are often overlooked. This report is one of the first to specifically study LGBTQ youth who are AAPI by describing the mental health and well-being of a national U.S. sample of nearly 3,600 AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who participated in our National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health.

METHODOLOGY

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data through an online survey platform between October and December 2020. A sample of LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. The final analytic sample consisted of 34,759 LGBTQ youth. In the survey, all youth were asked, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, more than one race or ethnicity, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, White/Caucasian, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Youth who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question to select with which races or ethnicities they identified. If youth chose Asian/Asian American at any point, they were asked, “You said that you were Asian/Asian American. With which of the following ethnicities do you most closely identify?” with response options: Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese, Thai, Vietnamese, and Another Asian (please specify). The current analyses include the 3,594 (10%) LGBTQ youth who either identified as exclusively Asian/Asian American, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, or who identified as multiracial Asian/Asian American or Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, henceforth just referred to as AAPI unless otherwise specified. The overall survey included a maximum of 150 questions, including questions on considering and attempting suicide in the past 12 months taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020) and measures of anxiety and depression based on the GAD-2 and PHQ-2, respectively (Plummer et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2010). Each analysis was run separately for AAPI youth who identified as exclusively AAPI compared to those who were multiracial AAPI and another race/ethnicity. Additionally, findings specific to Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean, and Vietnamese LGBTQ youth are shared when sample sizes permit; these analyses do not include AAPI LGBTQ youth who are multiracial. Logistic regression models were used to predict attempting suicide in the past year, adjusting for sex assigned at birth, age, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

RESULTS

AAPI LGBTQ Youth Diversity

Race and Ethnicity

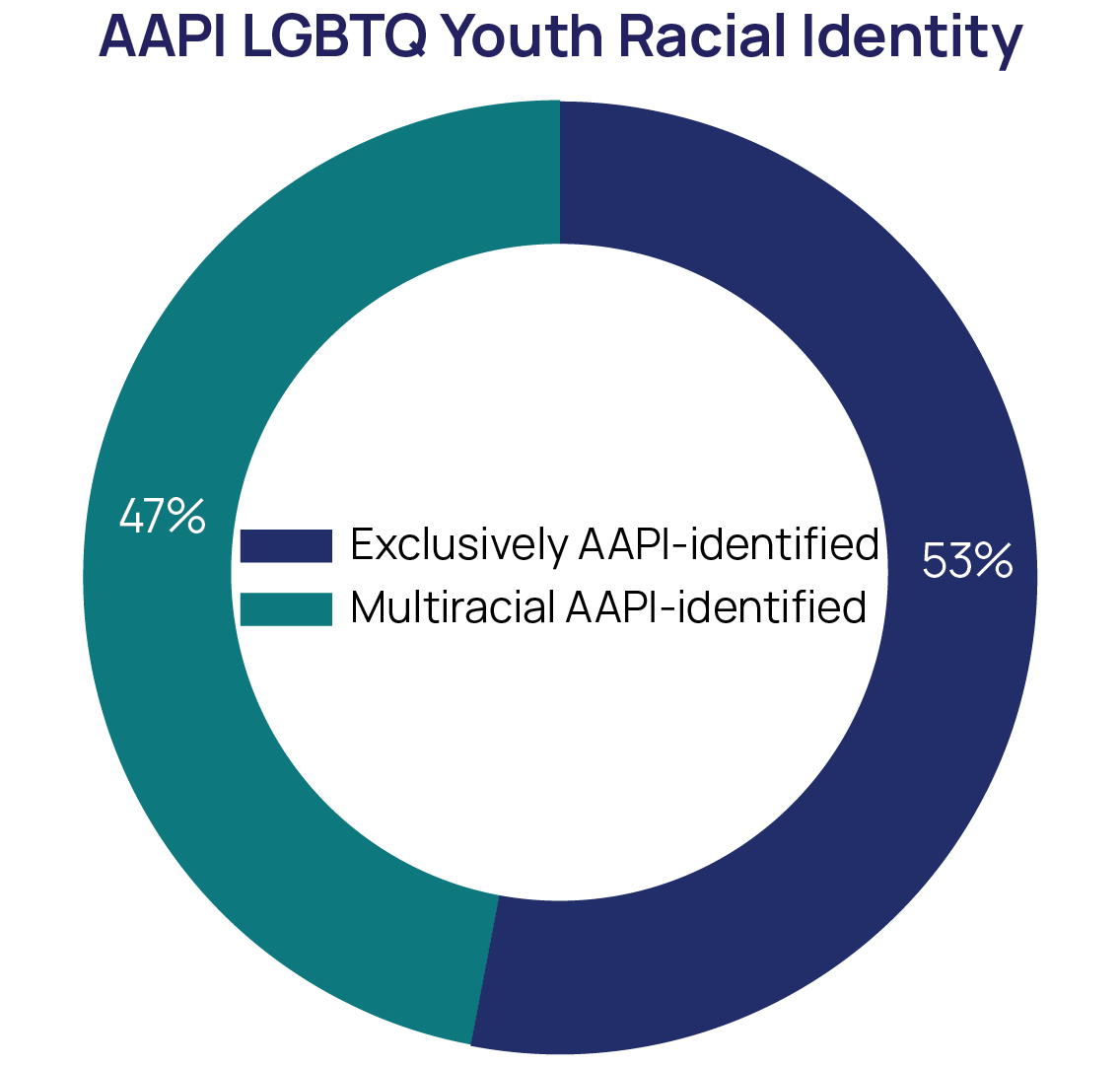

AAPI is a broad category that encompasses many different groups with different cultures and experiences, and the AAPI LGBTQ youth in our sample represented many of those. In our sample, 53% of AAPI LGBTQ youth identified as exclusively AAPI and 47% as multiracial AAPI (see sample demographics on Page 31). Overall, 27% were Chinese, either exclusively or in combination with another race or ethnicity, 21% Filipino, 15% Japanese, 14% Indian, 12% Korean, 9% Vietnamese, 3% Taiwanese, 3% Thai, 3% Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, and 10% identified as another Asian origin group not listed (e.g., Indonesian, Pakistani, Cambodian, Bengali, Laotian, and Hmong, among others). Among those who were multiracial AAPI, 78% were also White, 23% also Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, 15% also Black, 12% also Native/Indigenous, and 5% were also North African/Middle Eastern.

Overall, 15% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported being born outside of the U.S. This compares to 6% of the overall sample of LGBTQ youth. Additionally, 69% of AAPI LGBTQ reported that their parents were born outside of the U.S., compared to 31% of the overall LGBTQ youth sample.

While the vast majority of AAPI LGBTQ in our sample reported primarily speaking English at home, 20% primarily spoke another language at home, double that of the overall LGBTQ youth in the sample, including Mandarin, Tagalog, Korean, Vietnamese, Cantonese, Hindi, Bengali, Japanese, Tamil, and Telugu.

Sexual Orientation

The most frequent sexual identity among AAPI LGBTQ youth was bisexual (39%), followed by one in four AAPI LGBTQ youth (25%) who identified as gay or lesbian. An additional 16% of AAPI LGBTQ identified as pansexual, 14% as queer, 1% as straight, and 4% were unsure of their sexual identity. Youth also had the option to select other ways of describing their sexual orientation, and the more frequently selected identities among AAPI LGBTQ were asexual/ace spectrum (17%), biromantic (14%), demisexual (9%), panromantic (9%), polyamorous (8%) and a preference to not use labels (9%). Overall, AAPI LGBTQ youth’s sexual identities largely mirror those of the overall LGBTQ youth sample, 37% of whom identified as bisexual, 28% gay or lesbian, 19% pansexual, 12% queer, 1% straight, and 4% stated they were unsure of their sexual identity.

Gender Identity and Expression

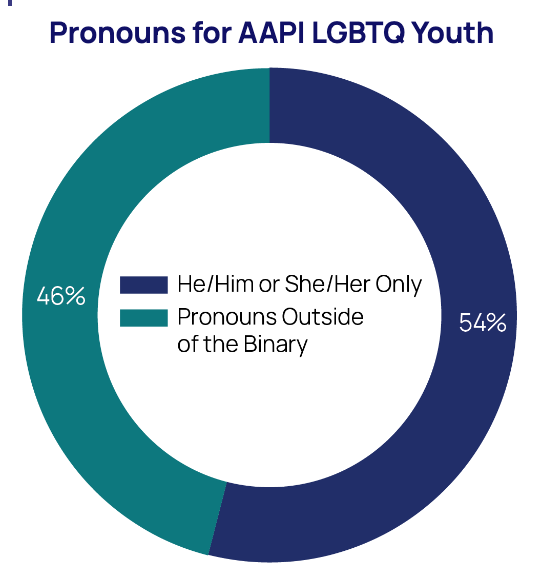

Overall, 38% of AAPI LGBTQ youth identified as transgender or nonbinary. Rates of AAPI youth endorsing a transgender or nonbinary identity ranged from 26% among Indian LGBTQ youth to 42% among Korean LGBTQ youth. Additionally, 46% of the AAPI LGBTQ youth in our sample used pronouns or pronoun combinations that fell outside of the binary construction of gender, such as they/them exclusively or a combination of they/them and she/her or he/him. Similar to sexual identity, rates of AAPI youth who were transgender or nonbinary were similar to that of the overall sample of LGBTQ youth: 38% were transgender or nonbinary, and 43% used pronouns that fell outside of the binary construction of gender.

Mental Health and Well-Being Among AAPI LGBTQ Youth

Anxiety and Depression

Overall, AAPI LGBTQ youth report rates of anxiety and depression that are similar to those reported by all LGBTQ youth; however, differences emerged among AAPI LGBTQ youth. More than two out of three AAPI LGBTQ youth reported symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in the past two weeks (68%). The rates were higher among AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth (74%) compared to cisgender AAPI LGBQ youth (62%), and among AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 13-17 (70%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 18-24 (63%). There were some differences within AAPI LGBTQ youth, with Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth reporting the highest rates of anxiety (70%) and Vietnamese LGBTQ youth reporting the lowest rates of anxiety (57%); however, rates were largely similar.

Overall, three out of five AAPI LGBTQ youth reported symptoms of major depressive disorder in the past two weeks (61%). Similar to anxiety, depression symptoms were higher among AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth (71%) compared to cisgender AAPI LGBTQ youth (52%), and younger AAPI LGBTQ youth (66%) compared to older AAPI LGBTQ youth (52%). There were also differences within AAPI LGBTQ youth, with rates of depression being highest among Vietnamese LGBTQ youth (67%) and lowest among Chinese LGBTQ youth (52%).

Self-Harm and Suicide Risk

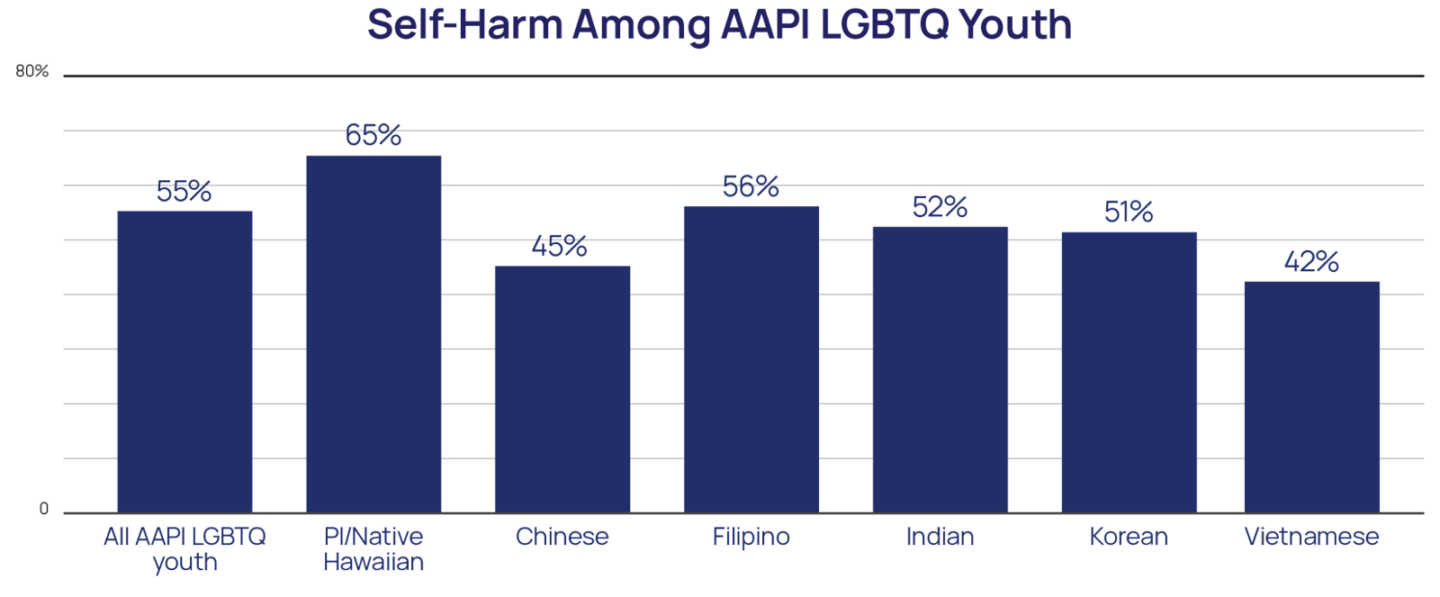

Both self-harm, hurting one’s self on purpose, and risks for suicide were similar for AAPI LGBTQ youth overall compared to those reported by LGBTQ youth in our sample. Self-harm was reported by 55% of AAPI LGBTQ youth, with rates being higher among AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth (66%) compared to cisgender AAPI LGBQ youth (44%), and AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 13-17 (63%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 18-24 (40%). The rates of self-harm differed among AAPI LGBTQ youth, with 65% of Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth reporting self-harm compared to 42% of Vietnamese LGBTQ youth.

Forty percent (40%) of AAPI LGBTQ youth seriously considered suicide in the past year. The rate was much higher among AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth, half of whom (50%) reported seriously considering suicide in the past year, compared to cisgender AAPI LGBQ youth (29%). It was also higher among younger AAPI LGBTQ youth (45%) compared to older AAPI LGBTQ youth (29%). Rates varied within AAPI LGBTQ youth, ranging from nearly half of Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth seriously considering suicide in the past year (49%) to 29% of Chinese LGBTQ youth.

Overall, 16% of AAPI LGBTQ youth attempted suicide in the past year, with AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth reporting nearly twice the rate (21%) of cisgender AAPI LGBQ youth (11%). Additionally, 20% of AAPI LGBTQ youth who were 13-17 years old reported attempting suicide in the past year compared to 9% of AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 18 to 24. Past-year suicide attempts varied among AAPI LGBTQ youth, ranging from 20% of Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth to 8% of Indian LGBTQ youth.

Risk Factors for Suicide Among AAPI LGBTQ Youth

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Outness

Deciding to share aspects of one’s sexual or gender identity with others, or being “out,” is a deeply personal choice, and choosing not to, or to only share with only a few trusted people, is equally as valid as sharing with everyone. Youth’s level of “outness,” or how many people youth are out to in their lives, may have a complex relationship with mental health. While being out may provide youth access to accepting and affirming connections with others like them, it also opens youth up to the potential rejection and harm that comes with others knowing their identity (Chang et al., 2021), particularly for youth who may still be dependent on others for their care.

Overall, 19% of AAPI LGBTQ youth were out to all or most of the people in their lives about their sexual orientation. This rate is lower than what is observed in the overall LGBTQ youth sample, with 27% being out about their sexual orientation to all or most of the people in their lives. Rates of outness to all or most people in their life differed among AAPI LGBTQ youth, ranging from 24% among Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth to 10% among Vietnamese LGBTQ youth. Additionally, 13% of transgender and nonbinary AAPI youth were out to all or most of the people in their lives about their gender identity, which is closer to the rate of the overall sample of transgender and nonbinary youth, 17% of whom were out to all or most of the people in their lives, though still lower. Rates of outness to all or most of the people in their lives also differed among AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth, with Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian transgender and nonbinary youth reporting the highest (14%) and Vietnamese transgender and nonbinary youth reporting the lowest (6%). AAPI LGBTQ youth who were out about their sexual orientation to all or most of the people in their lives reported higher rates of suicide attempts (19%) compared to those who were out to fewer people about their sexual orientation (15%). The same is true for AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth, with those who are out about their gender identity to all or most of the people in their lives reporting higher rates of past-year suicide attempts (25%) compared to those who were out to fewer (21%). Among all LGBTQ youth, those who were out about their sexual orientation also reported higher rates of suicide attempts (16%) compared to those those who were out to fewer people about their sexual orientation (14%); however, there was no difference in rates of suicide attempt among all transgender and nonbinary youth who were out to all or most of the people in their life or fewer. These results demonstrate how nuanced being out can be for LGBTQ youth.

Parental support (or rejection) is consistently related to mental health for all LGBTQ youth (Ryan et al., 2020). Therefore, specifically being out to a parent is an important indicator for whether youth are able to access this support in the first place or if it perhaps feels safer or more protective to not be out to a parent in the first place. While we did not assess the reason for not being out, 41% of AAPI LGBTQ youth were not out to at least one parent about their sexual orientation, compared to 29% of the overall sample of LGBTQ youth. Rates of AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not out to at least one parent about their sexual orientation differed for multiracial AAPI youth (33%) compared to AAPI youth who were not multiracial (48%). There were also differences among AAPI LGBTQ youth, with Vietnamese LGBTQ youth reporting the highest rate of not being out to at least one parent about their sexual orientation (60%) and Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth reporting the lowest rate of not being out about their sexual orientation to at least one parent (34%).

Relatedly, 51% of AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth reported not being out to at least one parent about their gender identity compared to 41% of the full sample of LGBTQ youth. Similar to sexual orientation outness to a parent, multiracial AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth reported lower rates of not being out to at least one parent (44%) compared to AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth who were not multiracial (57%), and differences emerged within AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth, ranging from 60% of Vietnamese transgender and nonbinary youth not being out to at least one parent about their gender identity to 45% of Korean transgender and nonbinary youth not being out to at least one parent about their gender identity.

AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not out to their parents about their sexual orientation reported a lower rate of suicide attempts in the past year (12%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were out to at least one supportive parent (17%), and AAPI LGBTQ youth who were out to their parents but did not have at least one supportive parent (26%). Among AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth, youth who were out about their gender identity to unsupportive parents reported the highest rates of attempted suicide in the past year (31%); however, youth who were out about their gender identity to a supportive parent (20%) and youth who were not out to their parents about their gender identity (19%) reported similar rates of past-year suicide attempts, suggesting that support for gender identity from at least one parent didn’t reduce the rates of suicide attempts above not being out to parents for AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth.

Conversion Therapy and Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Change Attempts

Conversion therapy — attempts by licensed professionals (e.g., psychologists or counselors) or practices by religious leaders to alter sexual attractions and behaviors, gender expression, or gender identity — is still occurring despite a lack of evidence to support this practice and, conversely, mounting evidence illustrating associated harm (Green et al., 2020). Ten percent (10%) of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported having been exposed to conversion therapy, compared to 13% of the full sample of LGBTQ youth. Conversion therapy rates were higher for multiracial AAPI LGBTQ youth (13%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not multiracial (8%), though it is important to note that multiracial AAPI LGBTQ youth are also more out about their sexual orientation and gender identity compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who are not multiracial. Furthermore, among AAPI LGBTQ youth who were exposed to conversion therapy, 61% reported that it had been led by a personal religious leader, 52% by an outside religious leader, and 35% stated they’d experienced conversion therapy from a healthcare professional. Nearly all AAPI LGBTQ youth (86%) who were subjected to conversion therapy reported it occurred when they were younger than 18. AAPI LGBTQ youth who were subjected to conversion therapy had nearly three times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 2.70) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not.

Broader than conversion therapy, though certainly inclusive of it, are any attempts by someone to convince a young person to change their sexual orientation and gender identity. More than half of AAPI LGBTQ youth (55%) reported that someone attempted to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity. The majority of these attempts came from parents (33%) and friends (30%). Although these rates are lower than what is reported by the full sample of LGBTQ youth (36% and 34% respectively), these numbers are also likely impacted by the lower rates of outness among AAPI LGBTQ youth. AAPI LGBTQ youth who reported that someone tried to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity reported nearly three times the rate of suicide attempts (21%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not report that this happened (8%).

Discrimination Based on Multiple Identities

Due to potentially holding many marginalized identities, AAPI LGBTQ youth are susceptible to experiencing discrimination and victimization based on several identities including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual identity, and immigration status. All youth in our sample were asked if they had ever experienced discrimination based on their actual or perceived status in several different identities. In our sample of AAPI LGBTQ youth, 54% reported discrimination based on their race/ethnicity in the past year. AAPI LGBTQ youth who were multiracial reported lower rates of race/ethnicity-based discrimination in the past year (48%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not multiracial (60%). More than half (56%) of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported discrimination based on their sexual orientation in the past year. Additionally, 62% of AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth reported past-year discrimination based on their gender identity. Finally, 10% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported having been discriminated against based on their immigration status. The rates of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity were similar to the overall sample of LGBTQ youth, however, rates of discrimination based on race/ethnicity and immigration status were nearly double.

There were also important differences among AAPI LGBTQ youth. AAPI LGBTQ youth who were multiracial reported higher rates of sexual orientation-based discrimination (59%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not (53%). However, AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not multiracial reported higher rates of race-based discrimination (60%) and immigration status-based discrimination (13%) compared to multiracial AAPI LGBTQ youth (48% and 7%, respectively). Furthermore, while Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth reported the lowest rates of both race-based (39%) and immigration status-based (4%) discrimination, these youth reported the highest rates of discrimination based on sexual orientation (65%) and based on gender identity (77%). Comparatively, rates of race-based (66%) and immigration-based (17%) discrimination were highest among Chinese LGBTQ youth.

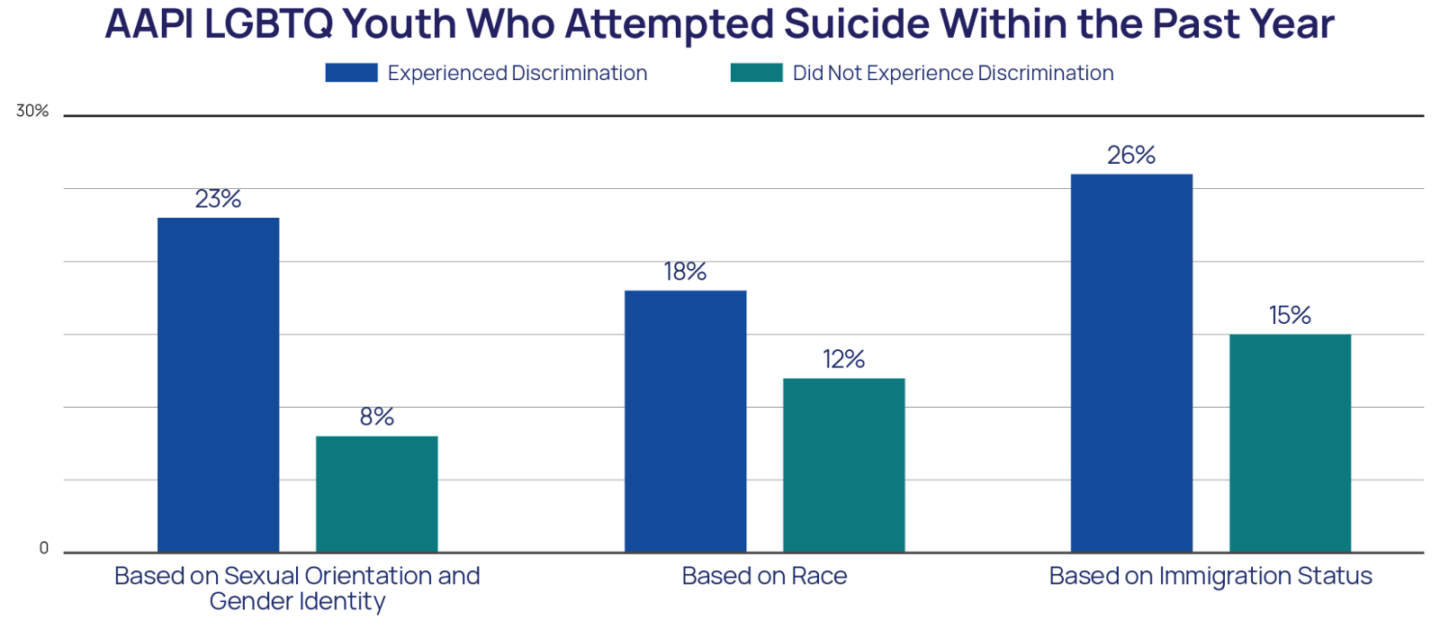

AAPI LGBTQ youth who experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity reported nearly three times the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (23%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not (8%). AAPI LGBTQ youth who experienced immigration-based discrimination had nearly double the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (26%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not (14%). Finally, AAPI LGBTQ youth who reported race-based discrimination reported higher rates of attempted suicide in the past year (18%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not (12%).

Victimization Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Overall, 17% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported having been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year, a rate similar to that of the full LGBTQ youth sample (19%). This includes 19% of AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth who were threatened or physically harmed based on their gender identity and 14% of AAPI LGBTQ youth who were threatened or physically harmed based on their sexual orientation. Multiracial AAPI LGBTQ youth reported higher rates of having been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity (20%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not multiracial (15%).

AAPI LGBTQ youth who had been physically harmed or threatened due to their sexual orientation or gender identity reported more than three times the rate of past-year suicide attempts (37%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not (11%).

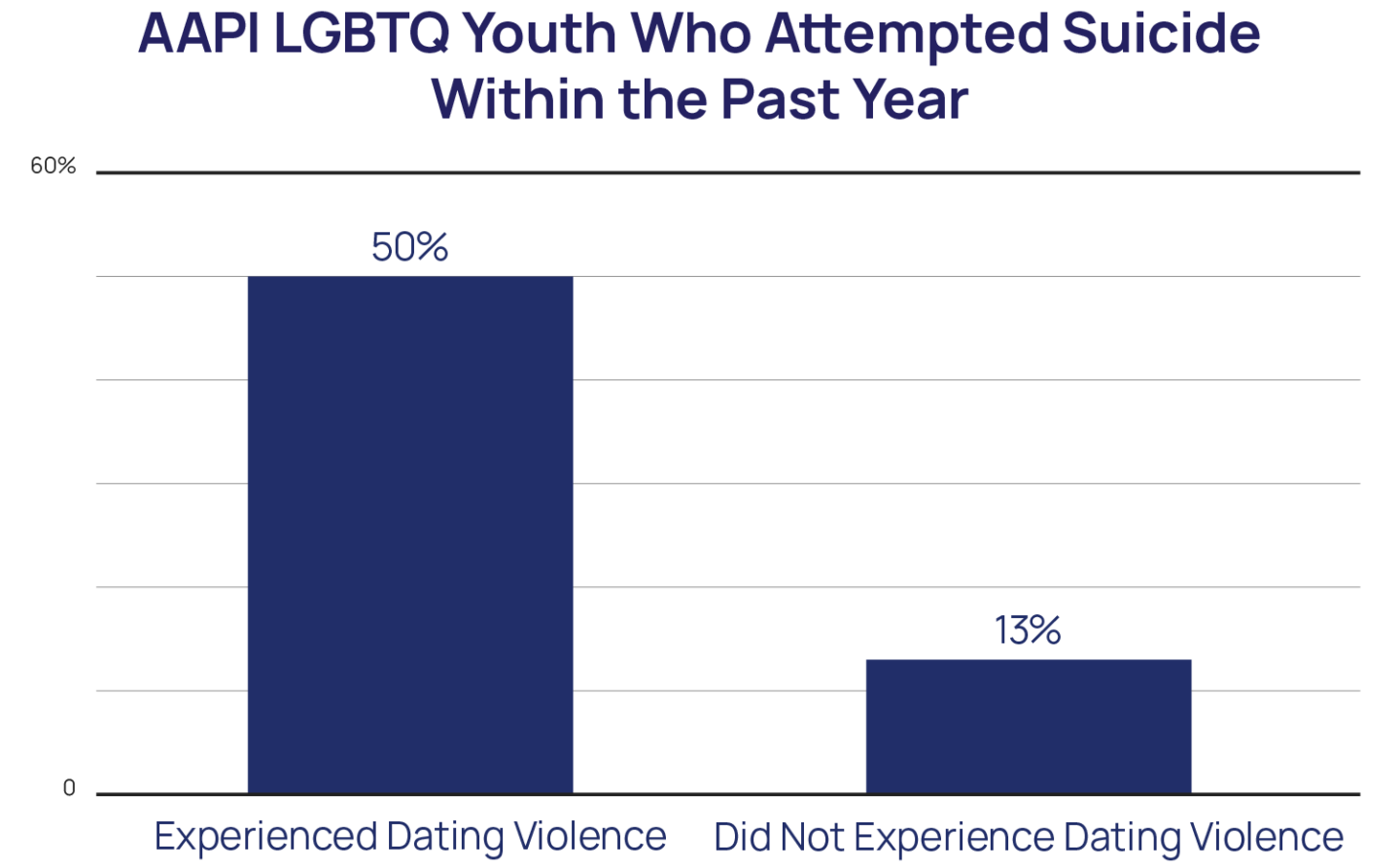

Dating Violence

Overall, 4% of AAPI LGBTQ youth had experienced dating violence victimization in the past year, compared to 6% of the overall LGBTQ youth sample. AAPI LGBTQ youth who were multiracial (6%) and AAPI youth who were transgender and nonbinary (6%) experienced double the rates of dating violence victimization in the past year compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not multiracial (3%) and who were cisgender (3%), respectively. AAPI LGBTQ youth who experienced dating violence victimization had nearly six times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 5.84) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not.

Suicide Protective Factors for AAPI LGBTQ Youth

Connectivity to Culture

Despite the many hardships they face, AAPI LGBTQ youth continue to find ways to thrive, and it is important to also understand aspects of their lives that help ameliorate the risk factors they are up against. One such protective factor for AAPI youth’s mental health is thought to be a strong connection to their cultural background (Yip & Fuligni, 2002; Yip et al., 2019). As a proxy for this, all youth were asked if their race/ethnicity was an important part of who they were. More than two out of three (72%) AAPI LGBTQ youth stated that their race/ethnicity was a somewhat or very important part of who they were. AAPI LGBTQ youth who said their race/ethnicity was a very important part of who they were reported nearly half the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (12%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who reported that their race/ethnicity was not at all important to them (23%). Overall, the more important AAPI LGBTQ youth’s race/ethnicity was to who they were, the lower their rate of past-year suicide attempts.

Importantly, fewer multiracial AAPI LGBTQ youth rated their race/ethnicity as a somewhat or very important part of who they were (68%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not multiracial (76%). Furthermore, there were differences among AAPI LGBTQ youth in how they rated the importance of their race/ethnicity as part of who they were, ranging from 82% of Indian LGBTQ youth reporting their race/ethnicity as somewhat or very important to 70% of Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth and 70% of Korean LGBTQ youth.

Supportive People

Having supportive people in their lives was also protective for AAPI LGBTQ youth. Overall, social support could be viewed as feeling like one’s family members and friends are there for them when needed or try to help them when they have troubles. AAPI LGBTQ youth who report high levels of family social support had 40% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = .60) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not have high family social support. Moreover, AAPI LGBTQ youth who report high levels of friend social support had 50% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = .50) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not have high social support from friends.

However, only one in five AAPI LGBTQ youth (20%) reported having high levels of social support from family. Even fewer AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth (15%) and AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 13-17 (15%) reported high levels of family social support. High social support from friends was more frequently reported among AAPI LGBTQ youth (74%) compared to high family support, similar to the overall LGBTQ youth sample. While there was no difference in social support from friends between AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth and AAPI cisgender LGBQ youth, younger AAPI LGBTQ youth reported lower rates (72%) compared to older AAPI LGBTQ youth (78%).

However, general social support may be very different from LGBTQ acceptance. With LGBTQ acceptance, youth feel accepted and affirmed in their identities. AAPI LGBTQ youth who had at least one parent who was accepting of their sexual orientation reported lower rates of past-year suicide attempts (16%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth whose parents were not accepting of their sexual orientation (26%). AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth who had at least one parent who was accepting of their gender identity also reported lower rates of past-year suicide attempts (20%) compared to those without accepting parents (31%). While high overall social support from family was not reported by most AAPI LGBTQ youth, 71% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported at least one parent was accepting of their sexual orientation, and 55% of AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth reported at least one parent was accepting of their gender identity.

That said, sexual orientation and gender identity acceptance can come from more than just a parent. Specifically, 83% of AAPI transgender and nonbinary youth reported they had at least one adult in their life who was accepting of their gender identity, with those having this support reporting a lower rate of past-year suicide attempts (22%) than those who did not (34%). AAPI LGBTQ youth who had at least one adult in their life who was accepting of their sexual orientation (85%) also reported lower rates of past-year suicide attempts (23%) compared to those who did not (18%), however, this difference was not statistically significant.

Affirming Spaces

Being able to be in spaces that affirm their LGBTQ identity was associated with lower rates of suicide attempts for AAPI LGBTQ youth. Overall, 56% of AAPI LGBTQ youth reported their school was LGBTQ-affirming, including 66% of AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 18-24 and 51% of AAPI LGBTQ youth ages 13-17. Rates of access to LGBTQ-affirming spaces were largely similar among AAPI LGBTQ youth with few exceptions.

AAPI LGBTQ youth who attended LGBTQ-affirming schools reported nearly half the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (12%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who did not attend LGBTQ-affirming schools (20%). AAPI LGBTQ youth who were in LGBTQ-affirming homes also reported a lower rate of suicide attempts in the past year (11%) compared to those whose homes were not LGBTQ-affirming (16%); however, only 27% of AAPI LGBTQ youth lived in an LGBTQ-affirming home. Finally, youth who reported feeling affirmed in their LGBTQ identity at community events reported lower rates of past-year suicide attempts (11%) compared to AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not able to find LGBTQ-affirming community events (16%). That said, few AAPI LGBTQ youth (15%) were able to access LGBTQ-affirming community events.

RECOMMENDATIONS

AAPI LGBTQ youth have a diversity of identities, experiences, and needs that demand attention from stakeholders across the spectrum in order to see improvements in well-being. The findings of this report show that AAPI LGBTQ youth are diverse in their sexual and gender identities and backgrounds, both among AAPI LGBTQ youth and compared to other LGBTQ youth. AAPI LGBTQ youth have rates of poor mental health indicators, including anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide, that are similar to the overall LGBTQ youth sample. That said, the true rates of AAPI LGBTQ who considered or attempted suicide in the past year might be higher than the current, and other researchers’, findings given a cultural phenomenon called “hidden suicidal ideation” where AAPIs underreport their suicidal ideation or intent (Chu et al., 2018). Additionally, AAPI LGBTQ youth are not only exposed to similar risks for suicide as other LGBTQ youth, such as discrimination and physical threat or harm based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, but are also exposed to stressors that are unique to the intersections of their multiple identities. Because prior research finds that AAPI individuals have the lowest rate of mental healthcare utilization across all of the broad ethnic groups in the U.S. (Abe-Kim et al., 2007), including our own finding that 60% of AAPI youth reported they wanted mental healthcare but did not receive it (Green et al., 2020), there is an unmistakable need to invest in AAPI LGBTQ youth mental health through increased access to culturally responsive treatment and prevention programs.

The AAPI community itself is diverse and differences across AAPI ethnicities should be taken into consideration when addressing AAPI LGBTQ youth mental health. The AAPI community is not a monolith, with a diversity of income, education, immigration status, language use at home, and experiences with discrimination and victimization across age, gender, and ethnicity. Transgender and nonbinary AAPI youth reported higher rates of all poor mental health indicators compared to cisgender AAPI LGBQ youth, as did AAPI youth ages 13-17 in comparison to older AAPI youth. Our subgroup analyses found that Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth are more out to others about their sexual orientation, report higher rates of discrimination and physical harm based on sexual orientation or gender identity, and also show the highest rates of poor mental health indicators compared to the other AAPI ethnicities we were able to analyze. These findings specifically point to an expressed need to address the unique challenges and experiences of Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian LGBTQ youth in prevention and intervention programs. Furthermore, Korean LGBTQ youth reported higher rates of being transgender and nonbinary and were also more out about their gender identity to at least one parent at higher rates compared to the other AAPI ethnicities we were able to analyze. Overall, these findings point to the need to examine findings separately for AAPI LGBTQ youth and, along with differences in culture and language, support interventions that are culturally salient for AAPI LGBTQ youth.

For AAPI LGBTQ youth, the intersections of their identities might mean that being out about their sexual orientation or gender identity is both a risk and protective factor. Prior research suggests that AAPI communities’ emphasis on being like others and not individuating oneself may result in coming out as LGBTQ being perceived as differentiating oneself from family and friends in a way that is frowned upon in some AAPI cultures (Yeh & Huang, 1996). However, being out can also provide much-needed social support. As such, our findings illustrate this duality in being out for AAPI LGBTQ youth. Consistent with other studies of AAPI LGBTQ adults (Dang & Hu, 2004) and our previous reports on AAPI LGBTQ youth, AAPI LGBTQ youth were infrequently out to their parents. Furthermore, AAPI LGBTQ youth who were not out to their parents generally reported lower levels of attempted suicide in the past year, suggesting that not being out might be allowing for continued access to the protection provided by familial and cultural connectivity. Despite this, when AAPI youth are out, parental support for LGBTQ identities is particularly protective for AAPI LGBTQ youth. Finally, while AAPI LGBTQ youth may not be out to their parents at a similar rate compared to other LGBTQ youth, their rates of outness and social support with friends are similar, and this support reduces their risk for suicide by more than half (The Trevor Project, 2020), suggesting support from friends as a significant protective factor for AAPI LGBTQ youth. Together, these findings underscore how incredibly personal the coming out process is for AAPI LGBTQ youth and the importance of youth having the choice to disclose their identity to others or not.

Intervention and prevention programs for AAPI LGBTQ youth must be culturally salient and equip parents and families to better support the AAPI LGBTQ youth in their lives. Our findings point to the protective nature of family, community, and racial/ethnic importance for AAPI LGBTQ youth. Additionally, one in five AAPI LGBTQ youth spoke a language other than English at home. This suggests that intervention and prevention programs for AAPI LGBTQ necessarily have to be culturally appropriate, by integrating cultural strengths into policies and practices and be linguistically accessible, in order for them to be salient and meaningful for AAPI LGBTQ youth. This includes programming at youth-serving organizations, schools, and the practices of healthcare professionals. Furthermore, given the importance of parents and family, providing resources and support for parents, family members, and valued community leaders of AAPI LGBTQ youth as an integral part of interventions is necessary. The diversity among AAPI LGBTQ youth also conveys that such interventions and prevention programs must be diverse themselves. Smaller, locally-based AAPI organizations that have the capacity to specifically address the unique needs of diverse AAPI youth and, given their position in the community, should be supported in efforts to become a safe and affirming environment for AAPI LGBTQ youth.

Research has largely failed AAPI LGBTQ youth’s mental health and more must be done to remedy this. The research community has historically done very little to explore the mental health of both AAPI youth and LGBTQ youth specifically. AAPI LGBTQ youth, at the intersection of these two identities, have been left out of important, life-saving research. Large-scale national studies, that have sample size capabilities, should be used to examine outcomes specific to AAPI LGBTQ youth. Furthermore, researchers should examine within-group differences whenever sample size constraints permit. An intersectional approach to this research, that allows for the unique experiences of multiple identities to inform the work, will provide invaluable insight into where organizations and advocates should focus their attention and resources.

The Trevor Project is committed to working toward improving and supporting the mental health and well-being of AAPI LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project’s existing efforts to uplift the voices of AAPI LGBTQ voices and experiences have included a discussion about the intersection of AAPI and LGBTQ identities as part of our celebration of AAPI heritage month, the release of our statement of support for Asian American communities grappling with anti-Asian sentiment, and an op-ed written by our Vice President of Communications discussing the coming out process as a Chinese American. Our crisis services team aims to provide all LGBTQ youth with high-quality, culturally-grounded care and has worked to create a diverse team of counselors and staff that aligns with the demographics of the youth we serve. Finally, our research team will continue its efforts to disseminate findings specific to AAPI LGBTQ youth and specific AAPI ethnicities to support a better understanding of AAPI LGBTQ youth within The Trevor Project and for our external partners and other stakeholders seeking to understand and address AAPI LGBTQ mental health.

| The authors of this report acknowledge and extend our deepest thanks to our Research Associate, Hannah Rosen, for providing feedback and guidance on the creation of this report. |

About The Trevor Project

The Trevor Project is the world’s largest suicide prevention and mental health organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, & questioning (LGBTQ) young people. The Trevor Project offers a suite of 24/7 crisis intervention and suicide prevention programs, including TrevorLifeline, TrevorText, and TrevorChat as well as the world’s largest safe space social networking site for LGBTQ youth, TrevorSpace. Trevor also operates an education program with resources for youth-serving adults and organizations, an advocacy department fighting for pro-LGBTQ legislation and against anti-LGBTQ policies, and a research team to examine the most effective means to help young LGBTQ people in crisis and end suicide. If you or someone you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386, via chat TheTrevorProject.org/Get-Help, or by texting 678-678.

This report is a collaborative effort from the following individuals at The Trevor Project:

Myeshia N. Price, PhD

Senior Research Scientist

Amy E. Green, PhD

Vice President of Research

Jonah P. DeChants, PhD

Research Scientist

Carrie K. Davis, MSW

Chief Community Officer

Recommended Citation: Price, M. N., Green, A. E., DeChants, J. P., & Davis, C. K. (2021).The mental health and well-being of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

Media inquiries:

Research inquiries:

REFERENCES

- Abe-Kim, J., Takeuchi, D. T., Hong, S., Zane, N., Sue, S., Spencer, M. S., Appel, H., Nicdao, E., & Alegría, M. (2007). Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the national Latino and Asian American study. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541

- Abu El-Haj, T. R. (2015). Unsettled belonging: Educating Palestinian American youth after 9/11. University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226289632.001.0001

- Alvarez, A. R., Kanuha, V., Anderson, M. K., Kapua, C., & Bifulco, K. (2020). “We Were Queens.” Listening to Kānaka Maoli perspectives on historical and on-going losses in Hawai’i. Genealogy, 4(4), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4040116

- Baams, L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038994

- Budiman, A., & Ruiz, N. G. (2021, April 29). Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-americans/

- Chang, C. J., Kellerman, J. K., Fehling, K. B., Feinstein, B. A., & Selby, E. A. (2021). The roles of discrimination and social support in the associations between outness and mental health outcomes among sexual minorities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(5), 607–616. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1037/ort0000562

- Chou, R. S., & Feagin, J. R. (2008). Myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Chu, J., Lin, M., Akutsu, P. D., Joshi, S. V., & Yang, L. H. (2018). Hidden suicidal ideation or intent among Asian American Pacific Islanders: A cultural phenomenon associated with greater suicide severity. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 9(4), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000134

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Crane, D. R., Ngai, S. W., Larson, J. H., & Hafen, M. (2005). The influence of family functioning and parent-adolescent acculturation on North American Chinese adolescent outcomes. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 54, 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00326.x

- Dang, A., & Hu, M. (2004). Asian Pacific American Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender people: A community portrait. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute. http://aapidata.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/lgbt-2004-apa-portrait.pdf

- Esperat, M. C., Inouye, J., Gonzalez, E. W., Owen, D. C., & Feng, D. (2004). Health disparities among Asian Americans and Pacific islanders. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 22(1), 135–160. doi: 10.1891/0739-6686.22.1.135

- Green, A.E., Price-Feeney, M., & Dorison, S. (2020). Breaking barriers to quality mental health care for LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/breaking-barriers-to-quality-mental-health-care-for-lgbtq-youth/

- Green, A. E., Price-Feeney, M., Dorison, S. H., & Pick, C. J. (2020). Self-reported conversion efforts and suicidality among US LGBTQ youths and young adults, 2018. American Journal of Public Health, 110(8), 1221–1227. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305701

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

- Human Rights Campaign (HRC) Foundation. (2019). 2019 LGBTQ Asian and Pacific Islander youth report. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/FINAL-API-LGBTQ-YOUTHREPORT.pdf

- Jeung, R., Yellow Horse, A. J., Lau, A., Kong, P., Shen, K., Cayanan, C., Xiong, M., & Lim, R. (2020). Stop AAPI Hate youth report. Stop AAPI Hate. http://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/Stop-AAPI-Hate-Youth-Report-9.14.20.pdf

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Underwood, J. M.(2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students — 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

- Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Zongrone, A. D., Clark, C. M., & Truong, N. L. (2018). The 2017 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/GLSEN-2017-National-School-Climate-Survey-NSCS-Full-Report.pdf

- Lee, S., Juon, HS., Martinez, G., Hsu, C. E., Robinson, E. S., Bawa, J., & Ma, G. X. (2009). Model minority at risk: Expressed needs of mental health by Asian American young adults. Journal of Community Health, 34(2), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9137-1

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Nakamura, N., Chan, E., & Fischer, B. (2013). “Hard to crack”: Experiences of community integration among first- and second-generation Asian MSM in Canada. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(3), 248–256. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1037/a0032943

- Park, G. C. (2011). Becoming a “model minority”: Acquisition, construction and enactment of American identity for Korean immigrant students. The Urban Review, 43(5), 620–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-010-0164-8

- Pittinsky, T. L., Shih, M., & Ambady, N. (1999). Identity adaptiveness: Affect across multiple identities. Journal of Social Issues, 55, 503–518. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00130

- Price-Feeney, M., Green, A. E., & Dorison, S. (2020). Understanding the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), 684–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.11.314

- Reyes, A. (2007). Language, identity, and stereotype among Southeast Asian American youth: The other Asian. Routledge.

- Ryan, C., Russell, S. T., Huebner, D., Diaz, R., & Sanchez, J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23, 205–213. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x

- Stevenson, H. W., & Stigler, J. W. (1992). The learning gap: Why our school are failing and what we can learn from Japanese and Chinese education. Simon & Schuster.

- Stop AAPI Hate. (2021). Stop AAPI Hate National report. https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/21-SAH-NationalReport2-v2.pdf

- Sue, D. W., Bucceri, J., Lin, A. I., Nadal, K. L., & Torino, G. C. (2009). Racial microaggressions and the Asian American experience. Asian American Journal of Psychology, S(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/1948-1985.S.1.88

- The Trevor Project. (2021). 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/The-Trevor-Project-National-Survey-Results-2021.pdf

- The Trevor Project. (2020). The Trevor Project research brief: Asian/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth mental health. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1r3EUMHxudiK1cP0H2pfkElDlVojto9gp/view

- Truong, N. L., Zongrone, A. D., & Kosciw, J. G. (2020). Erasure and resilience: The experiences of LGBTQ students of color, Asian American and Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth in U.S. schools. GLSEN. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED603844.pdf

- United States Census Bureau. (2019). Selected population profiles, American Community Survey 1-year estimates [Data set]. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=ACSSPP1Y2019.S0201&t=-02%20-%20All%20available%20basic%20races%20alone%20or%20in%20combination&tid=ACSSPP1Y2019.S0201&hidePreview=false

- United States Department of Justice. (2021). 2020 FBI hate crimes statistics. https://www.justice.gov/crs/highlights/2020-hate-crimes-statistics

- Wei, M., Russel, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Zakalik, R. A. (2004). Cultural equivalence of adult attachment across four ethnic groups: Factor structure, structured means, and associations with negative mood. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.51.4.408

- Yee, B. W. K., DeBaryshe, B. D., Yuen, S., Kim, S. Y., & McCubbin, H. I. (2007). Asian American and Pacific Islander families: Resiliency and life-span socialization in a cultural context. In F. T. L. Leong, A. Ebreo, L. Kinoshita, A. G. Inman, L. H. Yang, & M. Fu (Eds.), Handbook of Asian American psychology (pp. 69–86). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Yeh, C. J., & Huang, K. (1996). The collectivistic nature of ethnic identity development among Asian-American college students. Adolescence, 31, 645–661.

- Yip, T., & Fuligni, A. J. (2002). Daily variation in ethnic identity, ethnic behaviors, and psychological well-being among American adolescents of Chinese descent. Child Development, 73(5), 1557–1572. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00490

- Yip, T., Wang, Y., Mootoo, C., & Mirpuri, S. (2019). Moderating the association between discrimination and adjustment: A meta-analysis of ethnic/racial identity. Developmental Psychology, 55(6), 1274–1298. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000708

| Table 1: AAPI LGBTQ Youth Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (n = 3594) | Race/Ethnicity (n = 3594) | ||

| Under 18 | 67% | Multiracial AAPI (inclusive of other races) | 47% |

| 18 and over | 33% | Exclusively AAPI | 53% |

| Sex Assigned at Birth (n = 3555) | Chinese | 11% | |

| Female | 88% | Indian | 9% |

| Male | 12% | Filipino | 8% |

| Sexual Orientation (n = 3594) | Vietnamese | 4% | |

| Bisexual | 39% | Korean | 4% |

| Gay or lesbian | 25% | Pacific Islander / Native Hawaiian | 3% |

| Pansexual | 16% | Japanese | 2% |

| Queer | 15% | Thai | 1% |

| I am not sure | 4% | Taiwanese | 1% |

| Straight | 1% | Another Asian | 4% |

| Gender Identity (n = 3553) | Multiracial Asian (not inclusive of other race/ethnicities) | 7% | |

| Cisgender woman | 44% | Speak a language other than English at home (n= 3579) | 20% |

| Nonbinary | 28% | Just meeting basic needs (n = 3164) | 15% |

| Questioning | 11% | Youth born outside of the U.S. (n = 3576) | 15% |

| Transgender man | 8% | At least one parent/caregiver born outside of the U.S. (n = 3565) | 69% |

| Cisgender man | 8% | Region (n = 3594) | |

| Transgender woman | 1% | West | 39% |

| Pronouns (n = 3586) | South | 30% | |

| She or he only | 54% | Northeast | 16% |

| Pronouns outside of the gender binary | 46% | Midwest | 15% |