Introduction

Sex assigned at birth, gender, and gender identity impact individuals’ diverse lived experiences. Sex assigned at birth refers to the sex (usually male or female) given to a child at birth largely based on external genitalia. Gender usually refers to sociocultural systems mandating norms and expectations for individuals, and includes gender identity (Cole, 2009). Gender identity is one’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both, or neither. It has been established that one’s gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth (The Trevor Project, 2019). In recent decades, people including scholars, researchers, scientists, and activists have also argued against the idea that there are two discrete, stable, biologically determined categories into which all individuals can be sorted (Hyde, Bigler, Joel, Tate, & Van Anders, 2019). Included in this move away from a gender binary is the adoption of diverse gender identities. In this research brief, we explore the many different ways LGBTQ youth described their gender identity using data from The Trevor Project’s 2019 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health (The Trevor Project, 2019).

Results

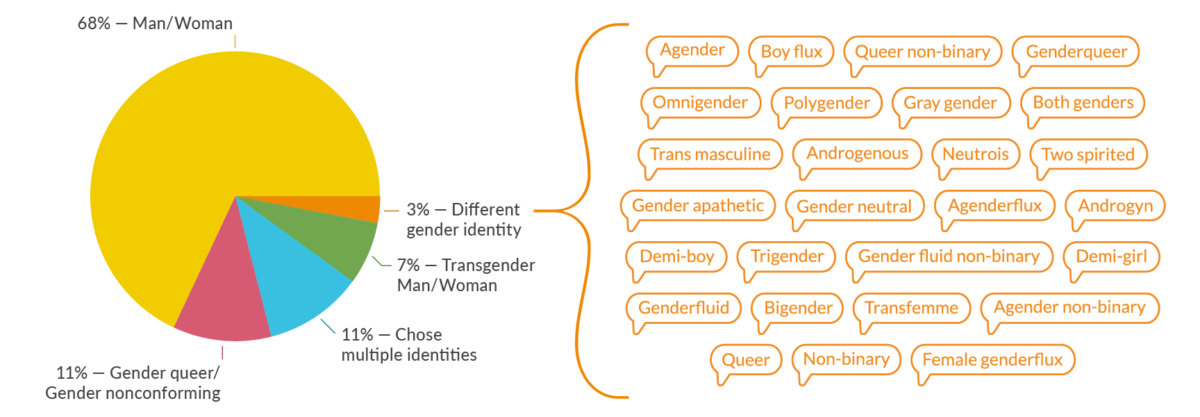

One in four LGBTQ youth identified outside of the gender binary. More specifically, 25% selected gender queer/gender nonconforming, a different identity, or chose multiple identities. Within the gender binary, 7% of youth exclusively selected transgender man or transgender woman.

The vast majority of youth who selected “different identity” and opted to write in their gender identity either identified as non-binary or genderfluid. Other write-in responses included youth who responded that they were questioning or unsure of their gender identity, or identified as demigender (e.g. demiboy, demigirl, demiflux, demifluid), agender, bigender, genderflux, queer, two spirit, gray gender, gender neutral, pangender, and polygender among others.

Many youth also used the write-in as an opportunity to explain the nuances of their gender identity and expression. For example, some youth specified that they were non-binary along with another adjective or gender identity label (e.g. non-binary masculine, non-binary femme, non-binary woman) or by providing multiple gender identities (e.g. agender & demiboy, genderfluid/androgynous, neutrois and genderfluid). Others included labels such transmasculine, transfeminine, or transgender non-binary. Some youth also simply used a pronoun or avoided any labels altogether in their attempts to explain the nuances of their gender identity (e.g. “I do not wear ‘girly’ clothes, makeup, or any ‘girly’ female things, but I am a girl. I am happy being a girl,” and “Female, but occasionally feels inaccurate/bound by gender assignment but are not trans; unsure if gender-nonconforming or not”).

While academic and clinical communities often think of transgender as an umbrella term that includes all youth whose gender identity is different from what they were assigned at birth, not all youth meeting that criteria identify as transgender. While 32% of the sample identified as either transgender or using labels outside of the man/woman binary, only 7% of LGBTQ youth in this study exclusively selected either transgender male or transgender female as their only gender identity. Further, among the 11% of youth who selected multiple options, the most common combinations were youth who selected both transgender man and man or those who selected both transgender woman and woman. An additional one percent of youth endorsed a sex assigned at birth that did not match their gender identity without also endorsing a transgender identity.

Methodology

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data through an online survey platform between February and September 2018. A sample of LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who resided in the United States were recruited via targeted ads on social media. A total of 34,808 youth consented to complete The Trevor Project’s 2019 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health with a final analytic sample of 25,896. The current analyses focused on the 25,502 youth who provided a response to the gender identity question. Gender identity was assessed using a two stage question. The first question asked youth, “What sex were you assigned at birth? (meaning the sex showing on your original birth certificate)” with options of either male or female. The second question asked, “What is your gender identity. Please select all that apply.” Response options included: 1) man; 2) woman; 3) trans male/trans man; 4) trans female/trans woman; 5) gender queer/gender non-conforming; 6) different identity (please state). The data presented here were coded to reflect exclusive choices.

Looking Ahead

Gender identity should be accurately assessed due to the enormous implications for mental health, affirmative care, and inclusivity. With the diversity in gender identities expressed in these data, assessments of gender and gender identity should never include the options of only “man” and “woman” — whether in academic, clinical, or organizational settings. Indeed, the gender identity of a full third of this sample would not have been accurately captured using just those terms.

Further, academically and clinically we tend to treat “transgender” as an umbrella term that includes anyone whose gender identity is different from their sex assigned at birth. However, only 13% of youth selected either transgender male or transgender female, either alone or in combination with other gender identities. This is despite the fact that 32% of youth in this sample did not identify as cisgender. Youth should be given options outside of transgender to identify that their gender is different from what was assigned at birth, such as non-binary, agender, and genderfluid.

At The Trevor Project, we embrace the diversity of gender identity across our programs and services to create safe, accepting, and inclusive spaces for LGBTQ youth. Additionally, we remain committed to advocating for inclusive and comprehensive assessments in clinical and research settings. We also provide training and education to ensure broader awareness of the diversity of LGBTQ youth identities, including the importance of affirming the language that youth use to describe themselves.

| ReferencesCole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 170 –180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014564Human Rights Campaign (HRC). Glossary of Terms. https://www.hrc.org/resources/glossary-of-terms. Accessed August 27, 2019.Hyde, J.S., Bigler, R.S., Joel, D., Tate, C.C., & Van Anders, S.M. (2019). The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist, 74(2), 171-193.The Trevor Project. (2019). Coming out: A Handbook for LGBTQ Young People. New York, New York: The Trevor Project. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/trvr_support_center/coming-out/The Trevor Project. (2019). National Survey on LGBTQ Mental Health. New York, New York: The Trevor Project. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2019/ |

For more information please contact: [email protected]