Youth's Lives Every Day

Summary

The Covid-19 pandemic has upended the lives of people around the world, with detrimental impacts on not only physical health but also mental health. Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, concerns have arisen around potential increases in suicide risk, particularly among marginalized populations. Prior to the pandemic, LGBTQ youth have been found to be at significantly greater risk for seriously considering and attempting suicide (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020). More research will continue to be conducted, but it is important that current conversations around Covid-19 and suicide risk be evidence-based and data-informed. This brief reviews existing research and data on the association between the Covid-19 pandemic and suicide risk, including as it relates to risk among LGBTQ youth.

Results

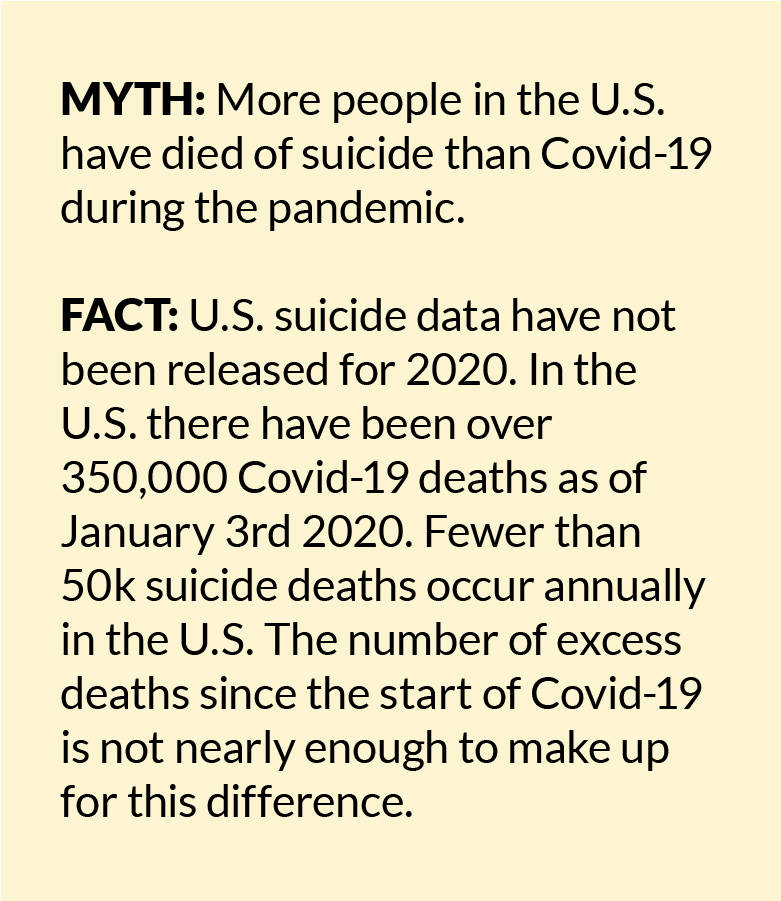

Deaths by suicide in the U.S. since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic

It is still too early to know the full effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on suicide rates. Within the U.S., national suicide death data for 2020 is not yet available (Kochanek et al., 2020). However, in order for suicide deaths to outpace deaths from Covid-19, they would need to occur at seven times the recent annual rate of nearly 50,000 to match the more than 350,000 deaths from Covid-19. Trends data from Massachusetts and Austin, Texas indicate no change and decreases, respectively in suicide deaths (Austin Police Department, 2020; Faust et al., 2020). Recent data from Maryland showed an overall downward trend; however, suicide deaths among those who were Black doubled (Bray et al., 2020). Globally, data points to no significant change in suicide rates among high-income countries, with less data on lower-income countries (John et al., 2020). However, sub-group trends can be hidden in overall rates. For example, among youth in the United Kingdom trends pointed to a potential increase in suicide deaths during their first lock-down; however, the sample size was small, and statistical significance was not achieved (Odd et al., 2020). Covid-19 related factors were found in the suicide deaths of nearly half of youth who died by suicide, including restrictions on education and activities, disruption to care and support services, tensions at home, and isolation. A study of school-aged children in Japan compared suicide deaths between March and May 2020 when schools were shut down to the same time periods in 2018 and 2019 and found no significant differences (Isumi et al., 2020). However, a more recent study of suicide deaths in Japan found a 7% increase in October compared to past years, with the highest increase among women under age 40 (Ueda et al., 2020).

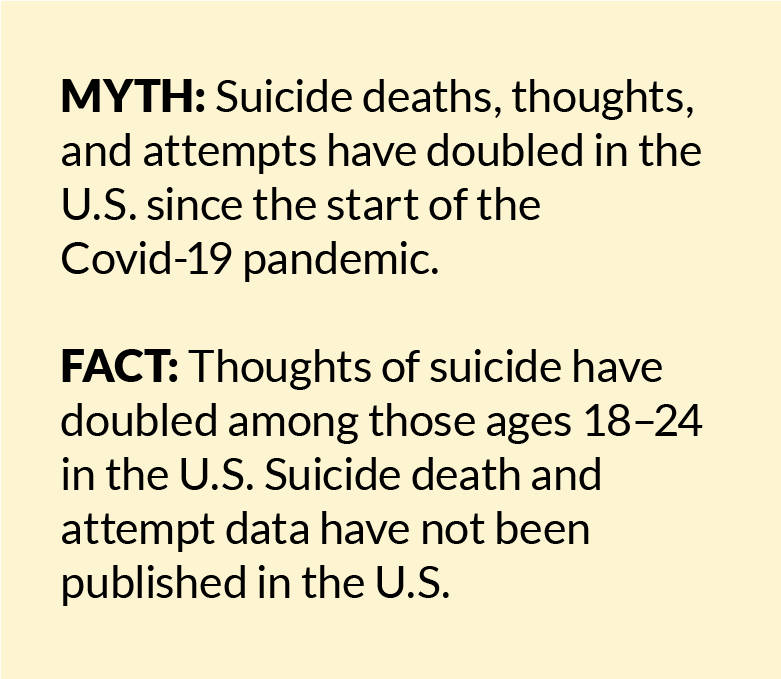

Thoughts of suicide in the U.S. since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic

In a spring 2020 survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 25.5% of those ages 18–24 reported having seriously considered suicide in the past 30 days (Czeisler et al., 2020). For comparison, 11.8% of those ages 18–25 reported seriously considering suicide in the past year in a 2019 survey (SAMHSA, 2020). Additionally, a study of U.S. adults found that individuals who were impacted by stay-at-home restrictions between April and June had significant increases in thoughts of suicide over that time period, while those who were not impacted by stay-at-home restrictions did not have a change in thoughts of suicide over time (Kilgore et al., 2020). A separate study that also looked at suicidal thoughts during stay-at-home orders found that the relationship was due to greater feelings of thwarted belongingness (Gratz et al., 2020), which can be described as loneliness resulting from a lack of reciprocal social relationships.

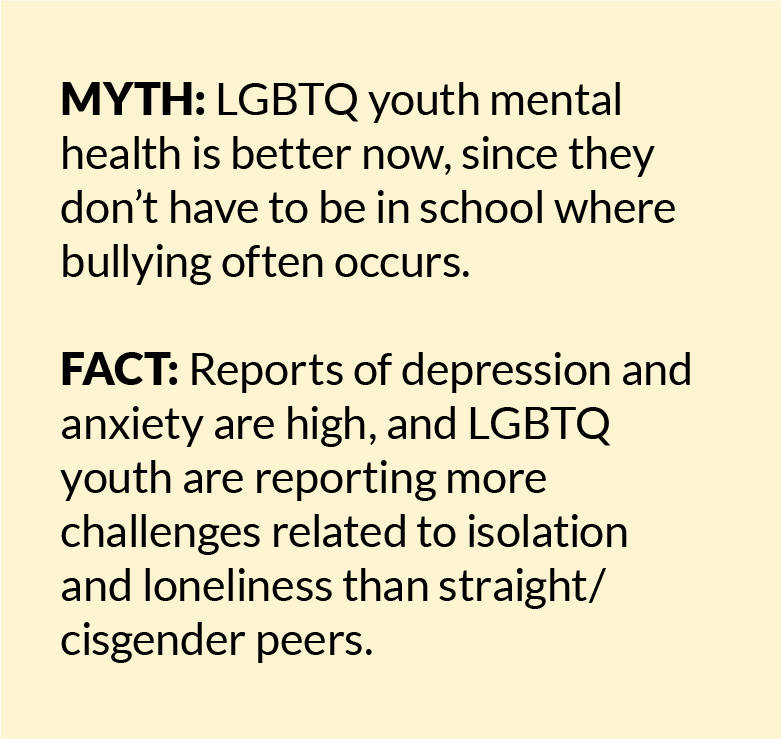

Covid-19 impact on LGBTQ youth mental health

In general, LGBTQ youth report nearly four times the rate of seriously considering suicide as their straight/cisgender peers (Johns et al, 2019; Johns et al., 2020). Although data is not yet available on suicidal thoughts or attempts among LGBTQ youth during the Covid-19 pandemic, recent polling data among youth ages 13–24 indicates that 35% of LGBTQ youth report feeling much more lonely since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic compared to 22% of cisgender/straight youth (The Trevor Project, 2020a). Further, 28% of LGBTQ youth report feeling much more anxious since the start of the pandemic compared to 18% of straight/cisgender youth.

Impact of increased time at home on LGBTQ youth mental health

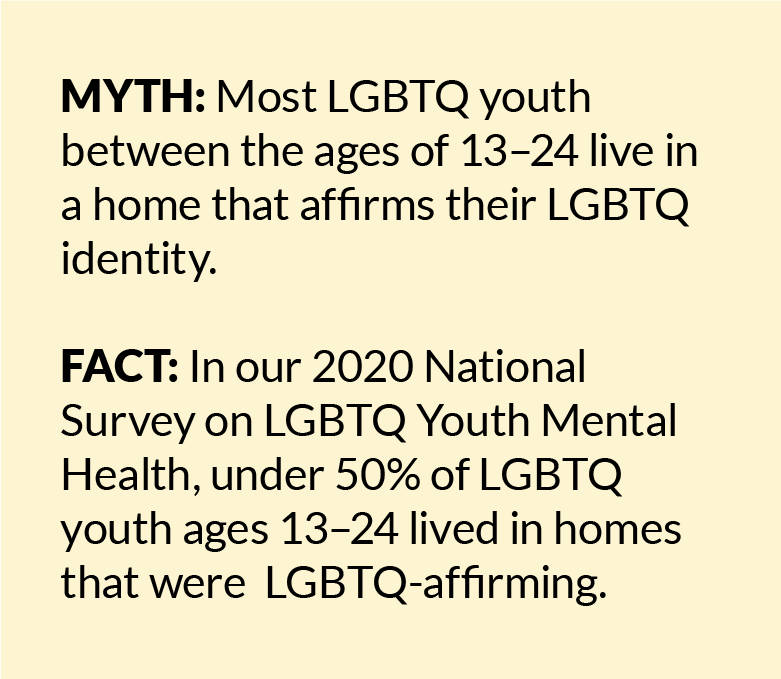

For many LGBTQ youth, their home environment is not a safe place, with 16% of LGBTQ youth, including 29% of transgender and nonbinary youth, reporting that they have felt unsafe in their home since the start of Covid-19 compared to 10% of cisgender/straight youth (The Trevor Project, 2020a). A study of an LGBTQ youth online chat-based support group at the beginning of the pandemic found that concerns reflected both experiences typical of many youth, such as adapting to online school, as well specific to LGBTQ youth, such as being stuck with unsupportive parents and the loss of safe spaces where they were affirmed in their identity, like their school’s gender and sexualities alliance (Fish et al., 2020). A recent study of LGBTQ college students found that nearly half (46%) lack families that know or support their LGBTQ identity (Gonzalez et al., 2020). More than 60% of this sample reported frequent psychological distress since the start of the pandemic, and those who lacked family support had 1.8 times greater odds of reporting frequent psychological distress.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted of empirical research conducted in 2020 on Covid-19 and suicide risk. Given the time needed to conduct and publish human subjects research, the vast majority of peer-reviewed publications consisted of speculative information based on past research rather than newly gathered data. As such, in addition to peer-reviewed articles, we searched for pre-prints, data briefs, and publications by government agencies in positions to provide population-level data about suicide risk. Further, given the dearth of data specific to LGBTQ youth and Covid-19, we also provide polling data conducted with this population.

Looking Ahead

There is a great need to collect additional data to better understand the relationships between Covid-19, suicide risk, and LGBTQ youth, while also providing support to LGBTQ youth who may be experiencing increased anxiety, loneliness, and rejection from their families. The available evidence highlights the need for better data surveillance systems in the U.S. to provide time-sensitive data on suicide, and to ensure that LGBTQ identities are accounted for in national data collection efforts, including death records. Improved collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data as part of violent death reporting is needed to fully understand suicide among LGBTQ individuals. Existing data highlights the importance of analyzing data by subgroups, particularly those who may hold marginalized identities. While data is lacking on actual deaths by suicide, trends in data point to an overall increase in struggles related to mental health and suicide, with LGBTQ youth reporting the highest levels of these struggles. The Trevor Project’s research team is working to provide critical data about the lives of LGBTQ youth during the Covid-19 pandemic, including mental health and suicide risk, through our ongoing National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. The use of evidence and data to inform public health policy and practices is imperative during Covid-19 and beyond. The Trevor Project’s advocacy and research teams are committed to ensuring that LGBTQ youth are included in that data, now and going forward.

Now more than ever, it’s important to take action to support the needs of LGBTQ youth. Even when practicing physical distancing, LGBTQ youth should know that they are not alone. Our previous research indicates that schools are reported as more affirming of LGBTQ and gender identities than homes (The Trevor Project, 2020b). While all school-aged youth are experiencing challenges related to school closures, these may be particularly felt by LGBTQ youth who no longer have regular access to an environment where they feel affirmed and supported. The Trevor Project is uniquely positioned to provide a range of support to LGBTQ youth throughout this pandemic. We have worked to maintain all of our crisis services 24/7. LGBTQ youth seeking community while physically distant from usual support systems can join TrevorSpace, the world’s largest safe space social networking site for LGBTQ youth. It provides LGBTQ youth and allies with a safe, affirming community and the opportunity to connect with people with shared experiences. Finding a safe community online can be a powerful way to deal with physical isolation, receive support, and explore their identity. If you or an LGBTQ young person you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal or would like support from a trained crisis counselor, The Trevor Project is available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386, via chat at TheTrevorProject.org/Help, or by texting START to 678678.

Recommended Citation: The Trevor Project. (2021). Evidence on Covid-19 Suicide Risk and LGBTQ Youth. https://doi.org/10.70226/FKXB8774

| ReferencesAustin Police Department (2020). APD Suicide Data. Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/487779502/APD-Suicide-Data Accessed on December 14, 2020. Bray, M., Daneshvari, N. O., Radhakrishnan, I., Cubbage, J., Eagle, M., Southall, P., & Nestadt, P. S. (2020). Racial differences in statewide suicide mortality trends in Maryland during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry, DOI: https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3938Kochaneck, K.D., Xu, J., & Arias, E. (2020). Mortality in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, 395, Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db395-H.pdf Accessed on December 22, 2020.Czeisler M.É., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the Covid-19 Pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1049–1057. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1Faust, J. S., Shah, S. B., Du, C., Li, S. X., Lin, Z., & Krumholz, H. M. (2020). Suicide deaths during the stay-at-home advisory in Massachusetts. medRxiv. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.20.20215343Fish, J. N., McInroy, L. B., Paceley, M. S., Williams, N. D., Henderson, S., Levine, D. S., & Edsall, R. N. (2020). “I’m kinda stuck at home with unsupportive parents right now”: LGBTQ youths’ experiences with COVID-19 and the importance of online support. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 450-452.Gonzales, G., de Mola, E. L., Gavulic, K. A., McKay, T., & Purcell, C. (2020). Mental health needs among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(5), 645-648.Gratz, K. L., Tull, M. T., Richmond, J. R., Edmonds, K. A., Scamaldo, K. M., & Rose, J. P. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness explain the associations of Covid‐19 social and economic consequences to suicide risk. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior.Isumi, A., Doi, S., Yamaoka, Y., Takahashi, K., & Fujiwara, T. (2020). Do suicide rates in children and adolescents change during school closure in Japan? The acute effect of the first wave of Covid-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 104680.John, A., Pirkis, J., Gunnell, D., Appleby, L., & Morrissey, J. (2020). Trends in suicide during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ, 371, m4352-m4352.Johns, M.M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L.C., Zewditu, D., McManus, T., et al. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school student–19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR, 68(3), 65-71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3Johns M.M., Lowry R., Haderxhanaj L.T., et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Suppl, 69,(Suppl-1):19–27. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3Killgore, W. D., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., Allbright, M. C., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Trends in suicidal ideation over the first three months of Covid-19 lockdowns. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113390.Odd, D., Sleap, V., Appleby, L., Gunnell, D., & Luyt, K. (2020). Child Suicide Rates during the Covid-19 Pandemic in England: Real-time Surveillance. Available at: https://www.ncmd.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/REF253-2020-NCMD-Summary-Report-on-Child-Suicide-July-2020.pdf Accessed on December 7, 2020. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2020). 2019 NSDUH Detailed Tables. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-detailed-tables Accessed on December 7, 2020.The Trevor Project (2020a). How Covid-19 is Impacting LGBTQ Youth. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Trevor-Poll_COVID19.pdf Accessed on December 7, 2020.The Trevor Project (2020b). Research Brief: LGBTQ & Gender-Affirming Spaces. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/2020/12/03/research-brief-lgbtq-gender-affirming-spaces/ Accessed on December 14, 2020.Ueda, M., Nordström, R., & Matsubayashi, T. (2020). Suicide and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. medRxiv. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.06.20207530 |

For more information please contact: [email protected]

© The Trevor Project 2021