Youth's Lives Every Day

Summary

LGBTQ youth are at elevated risk for suicide compared with straight/cisgender peers (Johns et al, 2019; Johns et al., 2020). This increased risk is linked to experiences of rejection, discrimination, and physical harm due to having an LGBTQ identity rather than being LGBTQ itself (Meyer, 2003). LGBTQ youth are also at greater risk of experiencing additional documented risk factors for suicide, including dating violence (Dank et al., 2014). Youth dating violence and youth suicide are both major public health concerns in the United States (CDC, 2012; CDC, 2020); however, little research has been conducted on their intersection among LGBTQ youth. Using data from a large, diverse sample of LGBTQ youth ages 13–24, this brief focuses on the association of physical dating violence and suicide attempts among LGBTQ youth, as well as LGBTQ youth reporting of physical dating violence experiences compared to others.

Results

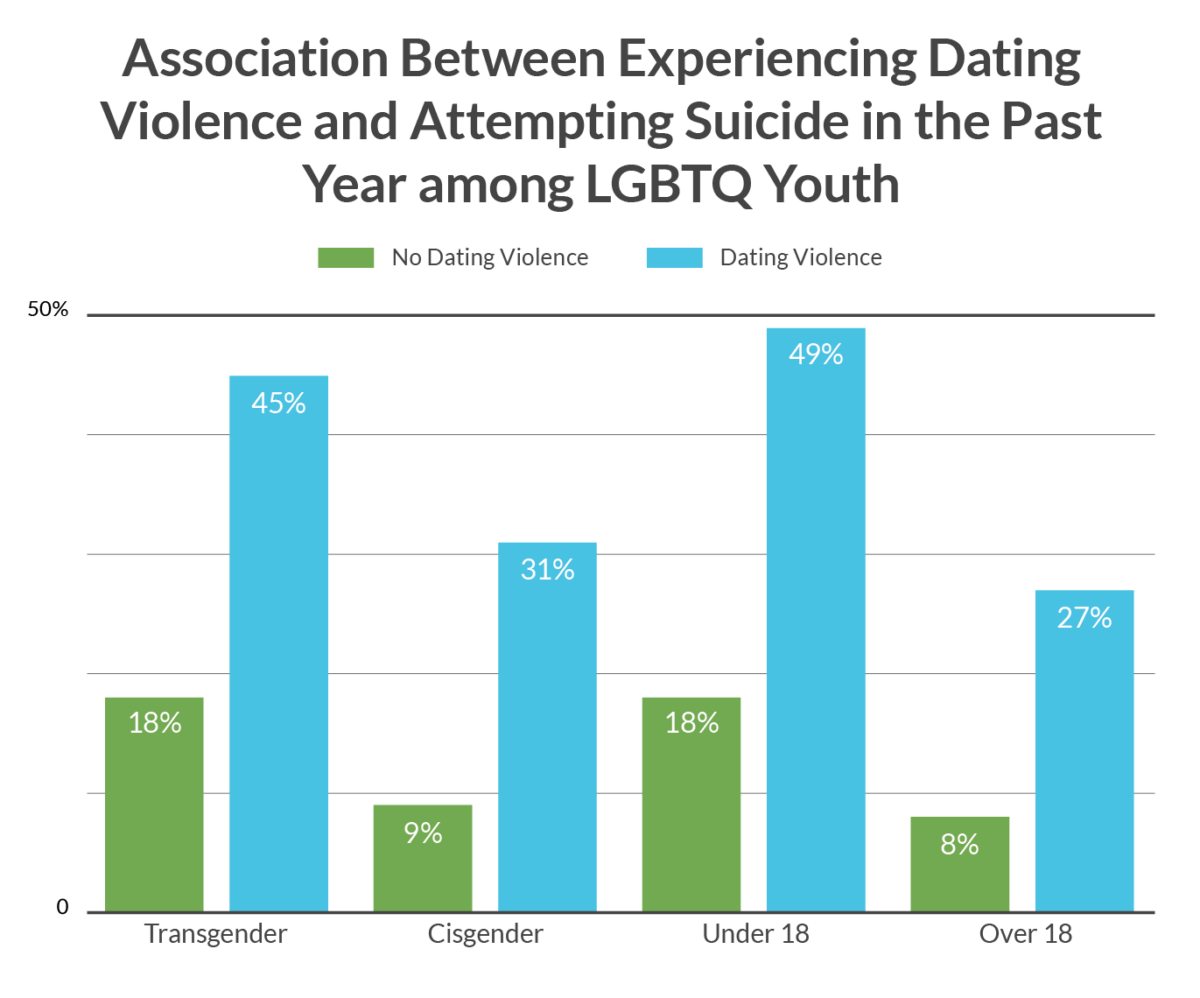

LGBTQ youth who experienced physical dating violence in the past year had significantly greater odds of reporting a past-year suicide attempt (aOR = 4.09, p<.001). Experiencing physical dating violence was associated with greater odds of a past-year suicide attempt across age ranges, gender identities, and race/ethnicities. Overall, 11% of LGBTQ youth who reported dating someone in the past year experienced physical dating violence. Although LGBTQ youth under age 18 had comparable odds of experiencing physical dating compared to those over 18 (aOR = 0.98, p = .257), there were significant differences within gender identity and race/ethnicity. Cisgender LGBQ girls/women had greater odds of reporting past-year dating violence compared to cisgender LGBQ boys/men (aOR = 1.17, p = .01). Transgender girls/ women (aOR = 1.72, p<.001), transgender boys/men (aOR = 1.57, p<.001), nonbinary youth (aOR = 1.51, p<.001), and youth who were questioning their gender (aOR = 1.38, p<.01) were significantly more likely to experience physical dating violence in the past year compared to cisgender LGBQ boys/men.

American Indian/Alaskan Native LGBTQ youth had more than 2.75 times greater odds of experiencing physical dating violence in the past year compared to White LGBTQ youth (aOR = 2.78, p<.001). Latinx LGBTQ youth (aOR = 1.30, p<.001) and youth who reported multiple race/ethnicities (aOR = 1.42, p<.001) also had greater odds of experiencing physical dating violence in the past year compared to White LGBTQ youth. Black LGBTQ youth had equal odds (aOR = 0.97, p = .78) and Asian/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth had 35% lower odds (aOR = 0.65, p<.001) of experiencing physical dating violence compared to White LGBTQ youth.

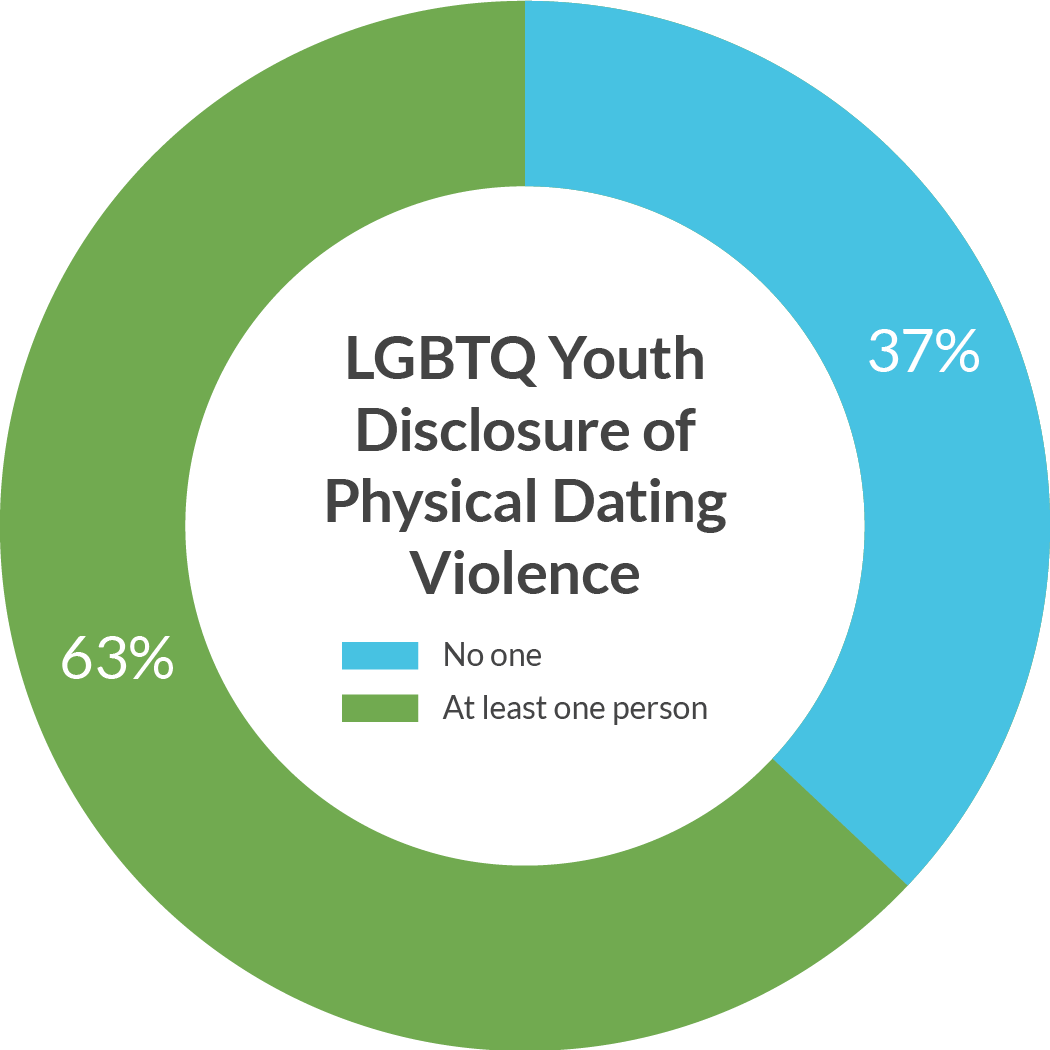

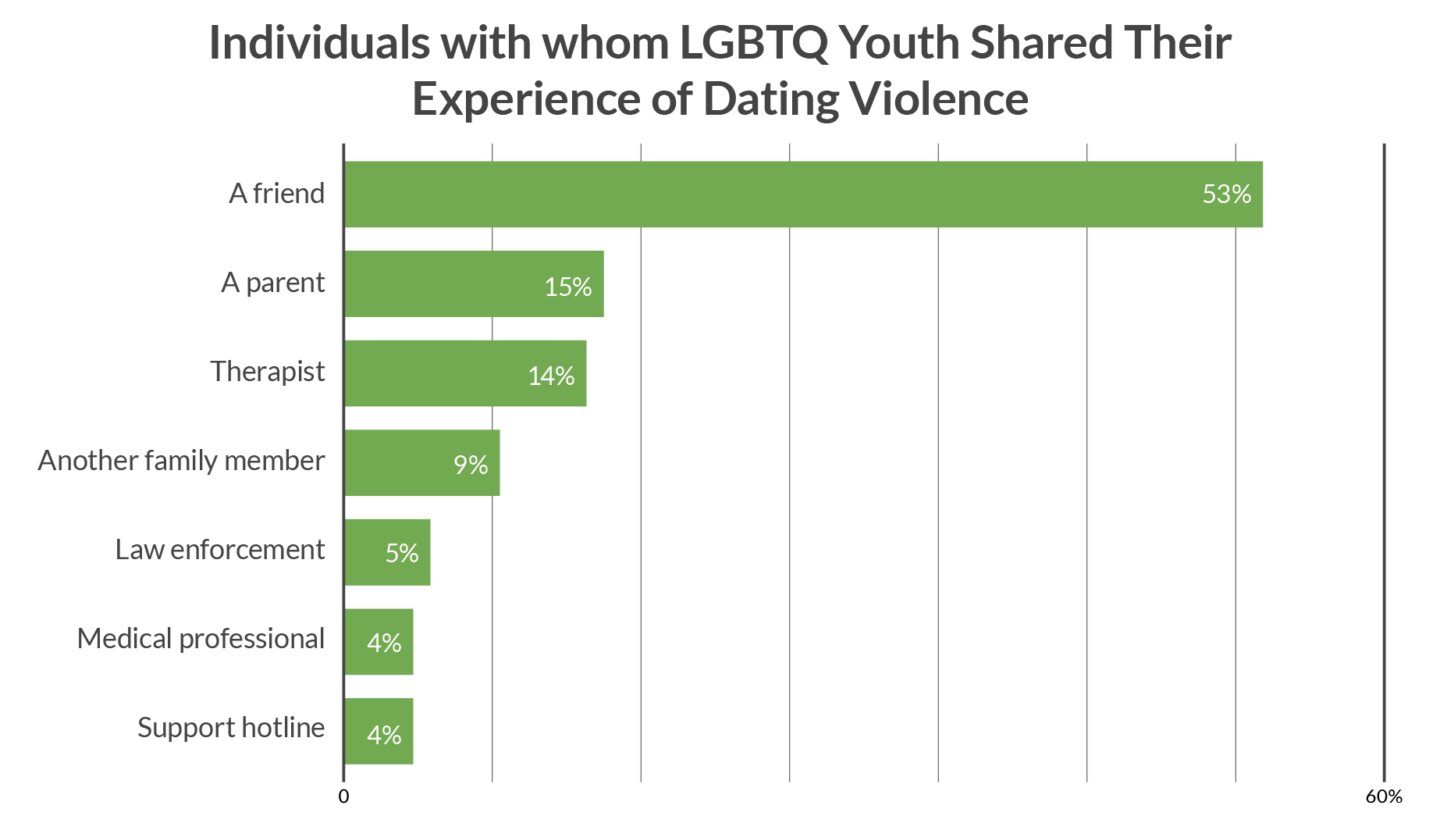

Over one-third (37%) of LGBTQ youth did not tell anyone about their experience of physical dating violence. Cisgender LGBQ boys/men (46%) and Black LGBTQ youth (47%) had higher rates of not telling anyone about their experience of physical dating violence. Friends (53%) were the most common individuals with whom LGBTQ youth reported sharing their experience of physical dating violence, followed by parents (15%) and therapists (14%).

Methodology

Data was collected from an online survey conducted between December 2019 and March 2020 of 40,001 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. Questions on physical dating violence (“During the past 12 months, how many times did someone you were dating or going out with physically hurt you on purpose?”) and attempted suicide (“During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”) were taken from the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey. A logistic regression model adjusting for gender identity, age, and race/ethnicity, was used to examine the association of past-year physical dating violence with past-year attempted suicide. A separate adjusted logistic regression model was used to examine disproportionality in experiencing physical dating violence by age, gender identity, and race/ethnicity. Finally, youth who experienced physical dating violence were asked “Did you tell anyone that someone you were dating or going out with physically hurt you on purpose?” and asked to endorse “no” or select one or more categories of individuals with whom they shared their experience.

Looking Ahead

LGBTQ youth are among those at highest risk for attempting suicide, and those who experience physical dating violence are at significantly greater risk. Unfortunately, most LGBTQ youth do not disclose their experiences with physical dating violence with adults such as parents, family members, therapists, and medical professionals who may be in a position to help them access professional support. However, most LGBTQ youth who have experienced physical dating violence report confiding in a friend. This data strongly indicates the need to invest in greater school-based programming to prepare young people with ways to identify and assist their peers who may be experiencing dating violence, as well as programs focused on developing and maintaining healthy relationships. Although this brief focused solely on physical dating violence, dating violence among LGBTQ youth can take many forms including emotional, verbal, financial, and sexual abuse as well as stalking and the use of online or digital means to intimidate and abuse (Love is Respect, 2020). It is imperative that dating violence prevention programs cover multiple forms of dating violence, include LGBTQ identities, and consider the cultural contexts in which youth live.

Given the intersection of suicide risk and dating violence among LGBTQ youth, there is also a need for organizations focused on addressing dating violence to be LGBTQ-inclusive and for suicide prevention organizations to be equipped to address the intersection of dating violence and suicide risk among LGBTQ youth. Further, there is a need to ensure that shelters supporting individuals who have experienced intimate partner violence and law enforcement responses to physical dating violence are sensitive to the experiences of LGBTQ individuals. At The Trevor Project, our crisis services team works 24/7 to provide support for all LGBTQ youth in crisis. Our counselor education incorporates training on dating violence among LGBTQ youth so that our crisis counselors are prepared to best support these youth in ways that respect all of their identities and experiences.

Recommended Citation: The Trevor Project. (2021). Physical Dating Violence and Suicide Risk among LGBTQ Youth. https://doi.org/10.70226/URIW1605

| ReferencesCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (2012). Suicide Prevention: A Public Health Issue. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ASAP_Suicide_Issue2-a.pdf Accessed on January 11, 2021.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Preventing Teen Dating Violence. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/teendatingviolence/fastfact.html Accessed on January 11, 2021.Dank, M., Lachman, P., Zweig, J. M., & Yahner, J. (2014). Dating violence experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(5), 846-857.Johns, M.M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L.C., Zewditu, D., McManus, T., et al. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school student–19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR, 68(3), 65-71.Johns M.M., Lowry R., Haderxhanaj L.T., et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Suppl, 69,(Suppl-1):19–27.Love is Respect (2020). Types of abuse. Available at: https://www.loveisrespect.org/resources/types-of-abuse/ Accessed on February 4, 2021.Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697. |

© The Trevor Project 2021