American history of resistance is a history of Black LGBTQ+ people. Advancements in civil rights and greater visibility of the LGBTQ+ community overall can be attributed to the efforts of Black LGBTQ+ folks; so much of what is popular and beloved in music, fashion, culture, and even language is because of the innovations and traditions of the Black queer diaspora. All of this is born out of the need to survive oppressive and violent conditions, distinguish themselves from their white LGBTQ+ counterparts who often enjoyed greater privilege.

When there are efforts to censor Black queer history in classrooms, to prevent trans folks from changing their gender markers or using the bathrooms they prefer, we must resist. Resistance of erasure is resistance to oppression.

This Black History Month, take a moment to learn about and honor the Black LGBTQ+ movements and people who have resisted throughout history.

The Cakewalk

What we know as the art of drag and ballroom today is born out of Black queer resistance to enslavement. The cakewalk, a dance performed by enslaved people, was meant to secretly mock plantation owners who frequently galavanted and gloated their expensive clothes. Their enslavers awarded the dancers cakes, unaware they were being blankly parodied. Later during the abolition period, “cakewalks” organized by the formerly enslaved served as a celebration of freedom and continued mockery of the enslavers, featuring attendees in extravagant costumes.

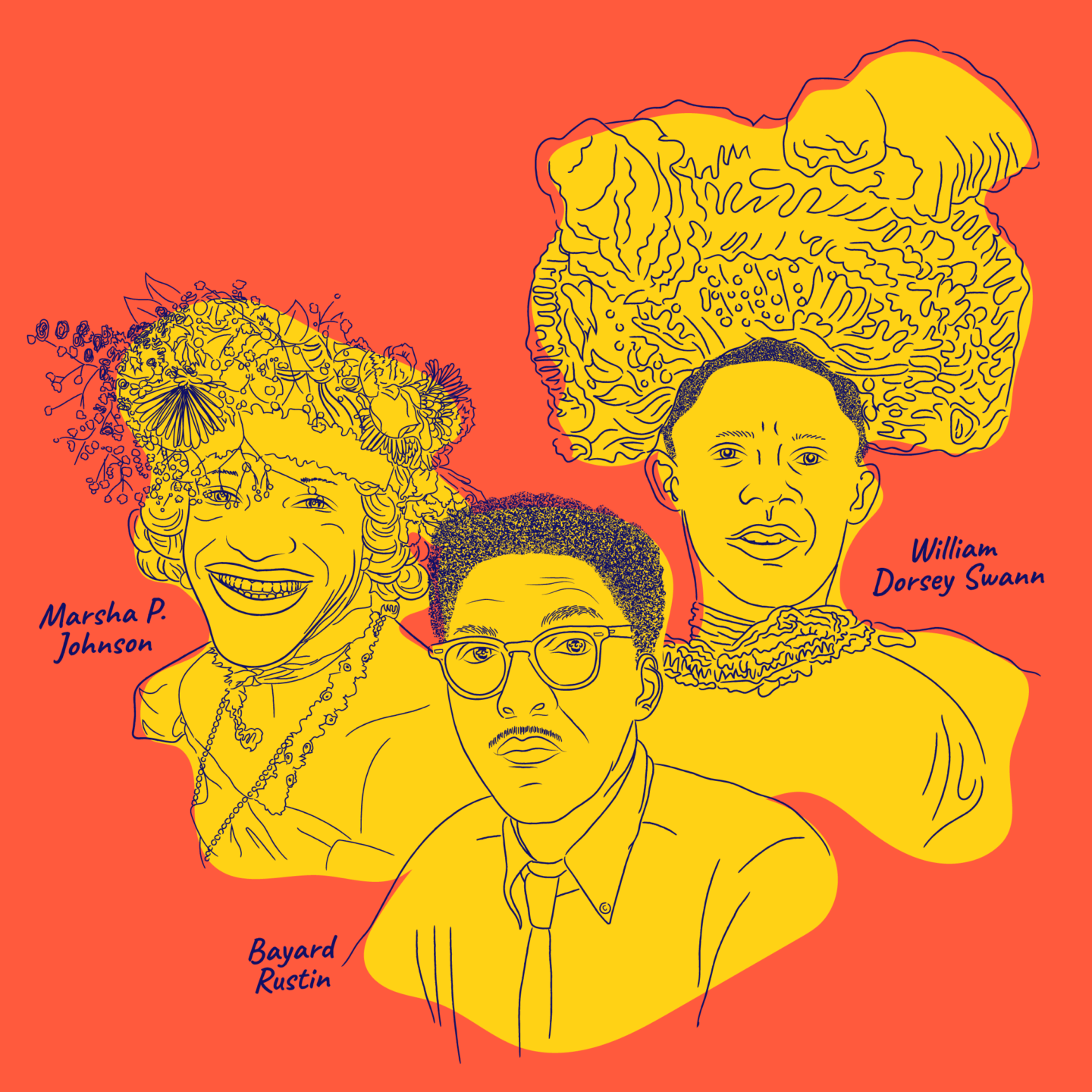

There is one particular person we can thank for the art of drag, and that is William Dorsey Swann, known now as the first drag queen. Swann, who was born into enslavement and survived to emancipation, was inspired by the “queens” of Washington D.C.’s Emancipation Day parades. He developed a form of dance for “glad rags,” also known as masquerade balls, and hosted cross-dressing balls for the community, many of which were raided by police.

This combination of dance performance and visual expression as a form of resistance survives in modern-day ballroom culture, famously depicted in the documentary film “Paris Is Burning.” Categories like “Executive Realness” serve as an opportunity for young Black queer folks — often denied positions of prominence in white society — to both mock the practices of the privileged and pretend to enjoy those privileges.

In the film, artist Dorian Corey notes: “Black people have a hard time getting anywhere. And those that do are usually straight. In a ballroom, you can be anything you want. You’re not really an executive, but you’re looking like an executive. And therefore you’re showing the straight world that ‘I can be an executive. If I had the opportunity, I could be one because I can look like one.’”

Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement

Many of us know about the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., but not as many know about Bayard Rustin, an “angelic troublemaker,” his mentor and collaborator during the civil rights movement of the 50s and 60s. Rustin was in fact the primary organizer of the historic March on Washington in 1936, perhaps the most famous civil rights protest of all time. Rustin was also openly gay, and spent much of his life dealing with political and legal persecution because of it (recently depicted in the 2023 film “Rustin”).

Rustin is quoted as saying, “One of the reasons that I decided that I should no longer remain in the closet came from an experience I had as a Black. I walked into a bus in the South… As I was going by the second seat to go to the rear, a white child reached out for the red necktie I was wearing and pulled it. Whereupon its mother said, ‘Don’t touch a [racial slur].’ Something happened, and I said to myself… I owe it to that child that it should be educated to know that Blacks do not want to sit in the back, and therefore I should get arrested letting all these white people in the bus know that I do not accept that. Now, it occurred to me shortly after that that it was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality, because if I didn’t, I was a part of the prejudice. I was aiding and abetting the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me.”

Marsha P. Johnson and the Invention of Pride

Community organizer and drag queen Marsha P. “Pay it no mind” Johnson has a similar legacy to Rustin. Johnson was a founding member of the Gay Liberation Front, as well as co-founder (with Sylvia Rivera) of the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, a group dedicated to housing and protecting houseless trans individuals in New York City. Johnson, along with noted activists Miss Major Griffin Gracy and Stormé DeLarverie, was a pivotal part of the Stonewall Riot, a rebellion as a result of a police raid on the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village. Though it is unclear whether a brick or a shot glass was thrown to incite the incident, and Johnson was not present during the beginning moments of the riot, Johnson is reported to exclaim, “I got my civil rights!” and became a major part of the uprising in the following days.

It is because of this riot and the work of Johnson and many others in the following year that we have Pride parades; the first ever Gay Pride was hosted one year after the Stonewall RIot, and Marsha marched. And though Marsha and collaborator Sylvia Rivera were banned from later Gay Pride events because they were drag queens, they marched proudly in front anyway.

These examples are by no means exhaustive or tell the whole story of Black LGBTQ+ resistance (James Baldwin, Alvin Ailey, Audre Lorde, Angela Davis, Andrea Jenkins, Langston Hughes, Miss Major Griffin Gracy, and more). But they are important and essential keys to the future. Remember the words of activist and Black queer liberation theorist Audre Lorde: “We do not have to romanticize our past in order to be aware of how it seeds our present. We do not have to suffer the waste of an amnesia that robs us of the lessons of the past rather than permit us to read them with pride as well as deep understanding.”

The Trevor Project is the leading suicide prevention and mental health organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer & questioning, and more (LGBTQ+) young people. If you or someone you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386 via chat www.TheTrevorProject.org/Get-Help, or by texting START to 678-678.