Summary

American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) individuals are among those with the highest rates of suicide deaths (Curtin & Hedegaard, 2019) and must contend with numerous social forces that threaten their well-being, including the historical and ongoing impacts of colonization and racism. “Historical trauma” describes the ways in which mental health disparities among AI/AN people result from a collective history of violence and erasure that can be transmitted across generations (Yellow Horse Brave Heart et al., 2011). Most studies of U.S. youth do not collect large enough samples to capture the experiences of AI/AN youth, who make up less than 2% of the population. The failure to obtain large enough sample sizes to examine AI/AN youth perpetuates inequities and inhibits progress towards dismantling structural forces that continue to oppress them. As LGBTQ youth attempt suicide at more than four times the rate of their straight/cisgender peers (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020), it is particularly important to examine suicide risk among AI/AN LGBTQ youth.

Results

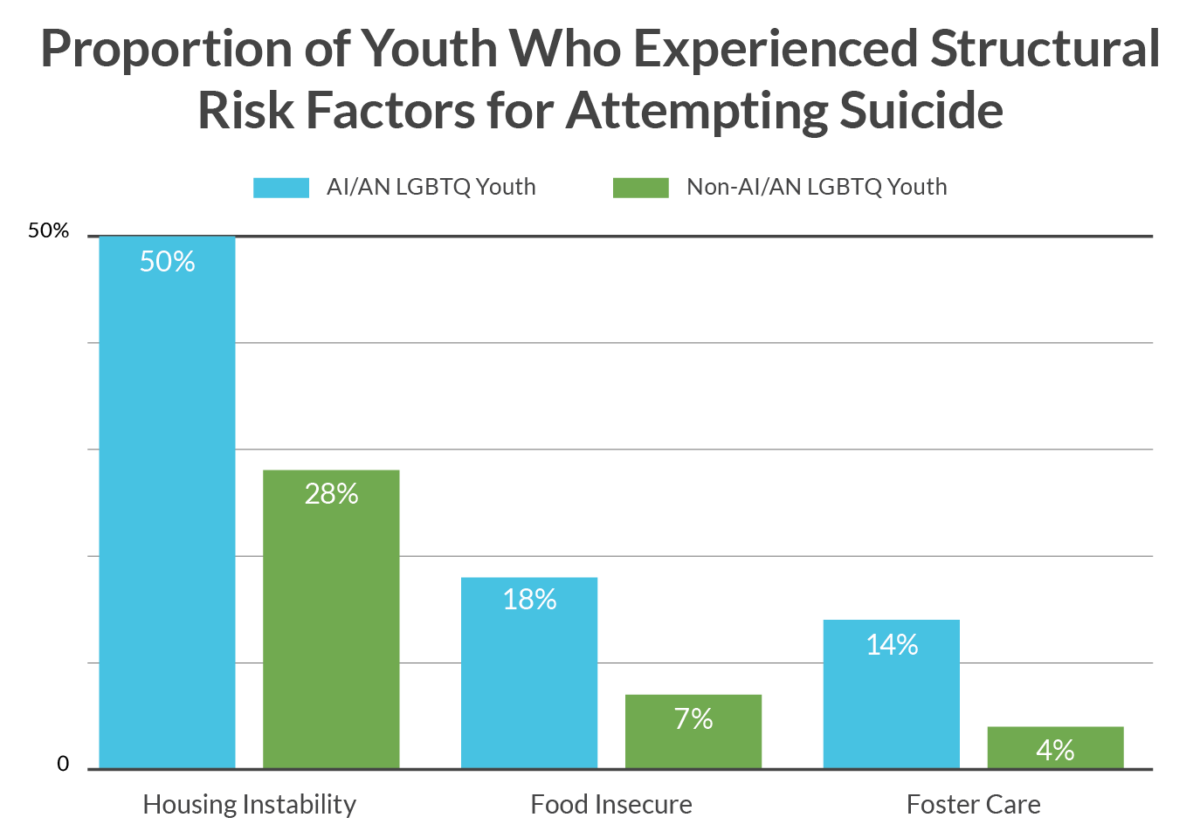

AI/AN LGBTQ youth were 2.5 times more likely to report a suicide attempt in the past year (33%) compared to non-AI/AN LGBTQ youth (14%), (aOR=2.57). Housing instability (50% vs. 28%), food insecurity (18% vs. 7%), and foster care (14% vs. 4%) were also disproportionately experienced by AI/AN LGBTQ youth compared to non-AI/AN LGBTQ youth. AI/AN LGBTQ youth who experienced foster care (aOR=3.57), housing instability (aOR=4.33), or food insecurity (aOR=4.97) had 3.5 to 5 times greater odds of reporting a suicide attempt in the past year.

AI/AN LGBTQ youth also experienced greater victimization and discrimination compared to non-AI/AN LGBTQ youth. Nearly half (49%) of AI/AN LGBTQ youth reported ever being physically harmed or threatened due to their LGBTQ identity compared to 31% of non-AI/AN LGBTQ youth (aOR=1.81). Among AI/AN LGBTQ youth, 70% reported discrimination due to their LGBTQ identity compared to 55% of non-AI/AN LGBTQ youth (aOR=1.61). AI/AN LGBTQ youth who reported LGBTQ-based victimization (aOR=3.29) or discrimination (aOR=2.64) were at more than 3 and more than 2.5 times the risk for attempting suicide, respectively. Further, 37% of AI/AN LGBTQ youth experienced race-based discrimination in the past 12 months, which was associated with a 30% greater odds of attempting suicide (aOR=1.31).

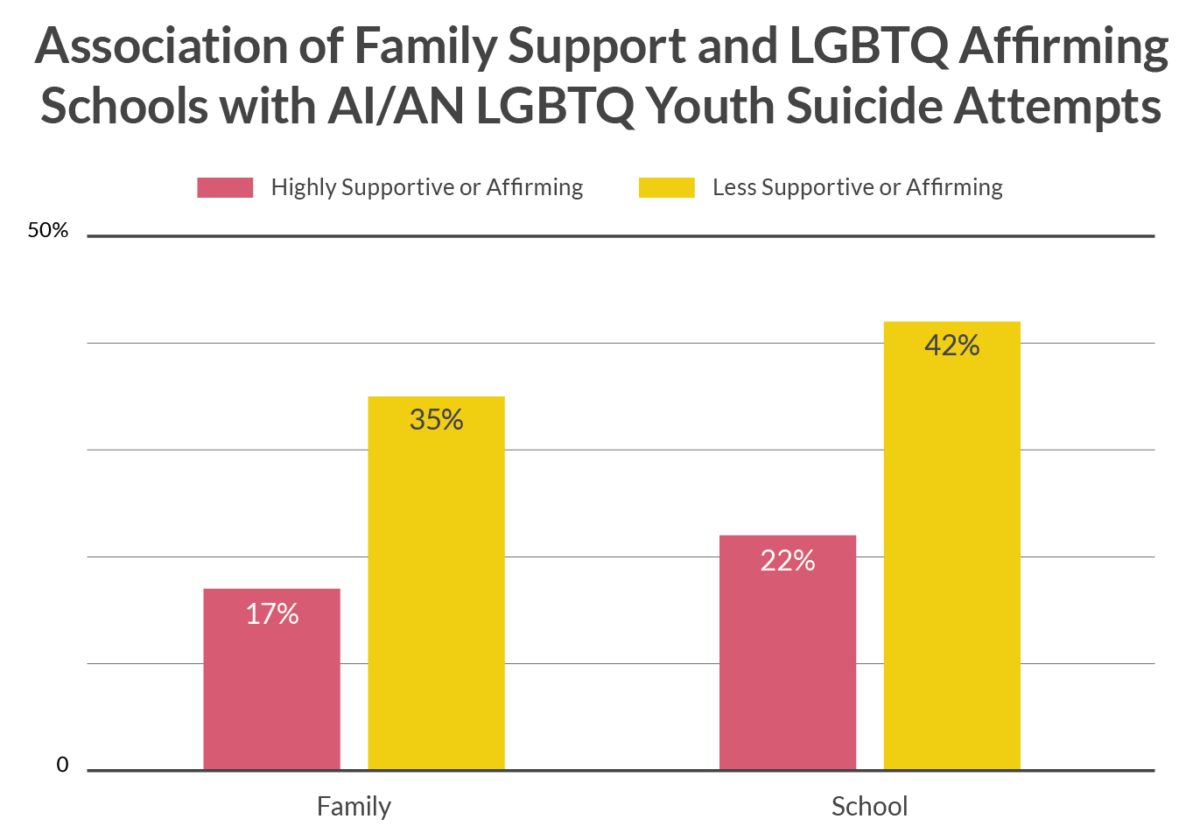

Family support and LGBTQ-affirming schools reduced suicide risk by more than half among AI/AN LGBTQ youth. Those who reported high levels of social support from family members were nearly 60% less likely to report a suicide attempt in the past year (aOR=0.42) compared to those with less family support. AI/AN youth who stated that their school was LGBTQ-affirming were also nearly 60% less likely to report a suicide attempt in the past year (aOR=0.43) compared to those whose schools were not LGBTQ-affirming.

AI/AN LGBTQ youth are diverse with respect to nation/tribe, spirituality, gender, and sexuality. The most commonly reported nations/tribes included Apache, Blackfoot, Cherokee, Chippewa, Choctaw, Lakota, Navajo, and Sioux. AI/AN LGBTQ youth were more likely to say that religion or spirituality was important to them (38%) compared to non-AI/AN LGBTQ youth (26%). Twenty percent of AI/AN LGBTQ youth are Two-Spirit. Half of AI/AN LGBTQ youth were transgender, nonbinary, or questioning their gender compared to 33% of non-AI/AN LGBTQ youth. The majority of AI/AN LGBTQ youth provided a multisexual identity including bisexual (38%), pansexual (27%), and queer (10%), with only 22% describing themselves as gay/lesbian compared to 33% of non-AI/AN LGBTQ youth.

Methodology

Data was collected from a quantitative online survey between December 2019 and March 2020. LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who resided in the U.S. were recruited via targeted ads on social media. The final analytic sample consisted of 40,001 LGBTQ youth. Findings among AI/AN LGBTQ youth are based on the 1156 AI/AN identified youth in our sample including, 39% (n=447) who identified solely as AI/AN and 61% (n=709) who identified as AI/AN along with one or more additional racial/ethnic identities. Youth who indicated an AI/AN identity were asked to provide the name of their nation/tribe and whether they are Two-Spirit (CIHR, 2020).1 The term Two-Spirit originated in 1990 at the Third Annual Intertribal Native American/First Nations Gay And Lesbian Conference to describe those who embody diverse sexualities, genders, gender expressions, and/or gender roles in their community (Pruden, 2019; Pruden, 2020). Two-Spirit reflects the connection to diverse genders and sexualities within indigenous culture and is not interchangeable with LGBTQ identity among indigenous people. Past-year suicide attempt was assessed with the question “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” with responses coded as “none” compared to “one or more.” Logistic regression models adjusted for youth gender identity and age, which were strongly associated with all study variables.

Looking Ahead

These findings highlight the devastating impact of historical oppression and trauma on AI/AN youth, evidenced by disproportionality in reports of foster care, housing instability, and food insecurity. Further, the compounding effects of discrimination indicate that AI/AN youth who are Two-Spirit/LGBTQ are also placed at greater risk for suicide by exposure to both LGBTQ-based stigma and racism. There is an urgent need to de-colonize systems that perpetuate the oppression of AI/AN people and to fund suicide prevention initiatives and research that are supportive of AI/AN youth. AI/AN suicide prevention experts have called for “reaching back into the root system of our people,” and drawing on spiritual and cultural strengths as a powerful protective factor (Heart of the Hawk Ali, 2020; Yellow Horse Brave Heart et al., 2011). To reduce suicidality, there is not only a need to make existing programs and practices more affirming of AI/AN and Two-Spirit/LGBTQ identities, but also to include key individuals in the lives of these youth such as community leaders, family members, and youth themselves in the development of suicide prevention initiatives. Our research team is committed to the ongoing dissemination of data that allows Trevor and others to better understand and address the needs of these youth. Further, our crisis services team works 24/7 to provide culturally-informed and affirming support to youth in crisis over the phone, online, and through text.

- The authors of this brief acknowledge and extend our deepest thanks to First Nations Cree scholar Harlan Pruden for providing guidance on the development of appropriate measures to ask youth about their tribal affiliation and Two-Spirit identity.

| ReferencesCanadian Institutes for Health Research Institute of Gender and Health (2020). What and who is Two-Spirit? Available at: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/igh_two_spirit-en.pdf Accessed on November 13, 2020.Curtin S.C. & Hedegaard H. (2019). Suicide rates for females and males by race and ethnicity: United States, 1999 and 2017. NCHS Health E-Stat.Heart of the Hawk Ali, S. (2020). Getting to “Zero” in Indian Country. Educational Development Center. Accessed on September 28, 2020 Available at: https://www.edc.org/blog/getting-zero-indian-countryJohns M.M., Lowry R., Andrzejewski J., et al. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students — 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 68, 67–71. Johns MM, Lowry R, Haderxhanaj LT, et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly, 69(Suppl-1):19–27. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3external Pruden, H. (2020). TWO-SPIRIT turns 40!! Two Spirit Journal. Available at: https://twospiritjournal.com/?p=973 Accessed on Oct 26, 2020. Pruden, H. (2019). Two-Spirit conversations and work: Subtle and at the same time radically different. In A. Devor, A.H. Thomas (Eds.), Transgender: A reference handbook (pp. 134-137). ABC-CLIO. Santa Barbara, CA.Yellow Foot Brave Heart, M., Chase, J., Elkins, J., & Altschul, D. B. (2011). Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 282-290. |

For more information please contact: [email protected]