Background

Parental and caregiver actions can play a pivotal role in the mental health of LGBTQ youth. Across multiple studies, a strong parent/caregiver-child relationship has been found to support good mental health among LGBTQ youth (Bouris et al., 2010). Research from the Family Acceptance Project has found that LGBTQ young adults who report high levels of family acceptance of their LGBTQ identity report higher levels of self-esteem, social support, and general health compared to their LGBTQ peers who report low levels of family acceptance (Ryan et al., 2010). LGBTQ young adults with high levels of family support are half as likely to report suicidal thoughts in the last six months and nearly half as likely to report suicide attempts (Ryan et al., 2010). Conversely, family rejection has been shown to be a source of minority stress among LGBQ adults in same-sex relationships (Rostosky & Riggle, 2017) and transgender youth (Toomey, 2021). Minority stress, in turn, can manifest in the form of poor mental health as LGBTQ youth attempt to navigate anti-LGBTQ environments, such as their home, schools, or communities (Meyer, 2003). LGBTQ young adults who report low levels of family acceptance of their LGBTQ identity report higher levels of depression, substance use, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Ryan et al., 2010). However, family can also be a source of strength for LGBTQ youth. A study of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents found that connecting with family is one strategy that young people use to cope with minority stress related to their sexual orientation (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2015). Parents and caregivers seeking to affirm their LGBTQ child sometimes ask what specific actions they can take to effectively communicate their support. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, which included the Family Acceptance Project’s list of supportive actions that parents or caregivers can take to support their child’s LGBTQ identity, this brief examines the frequency of LGBTQ-supportive actions by parents and caregivers and their association with suicide risk among LGBTQ youth.

Results

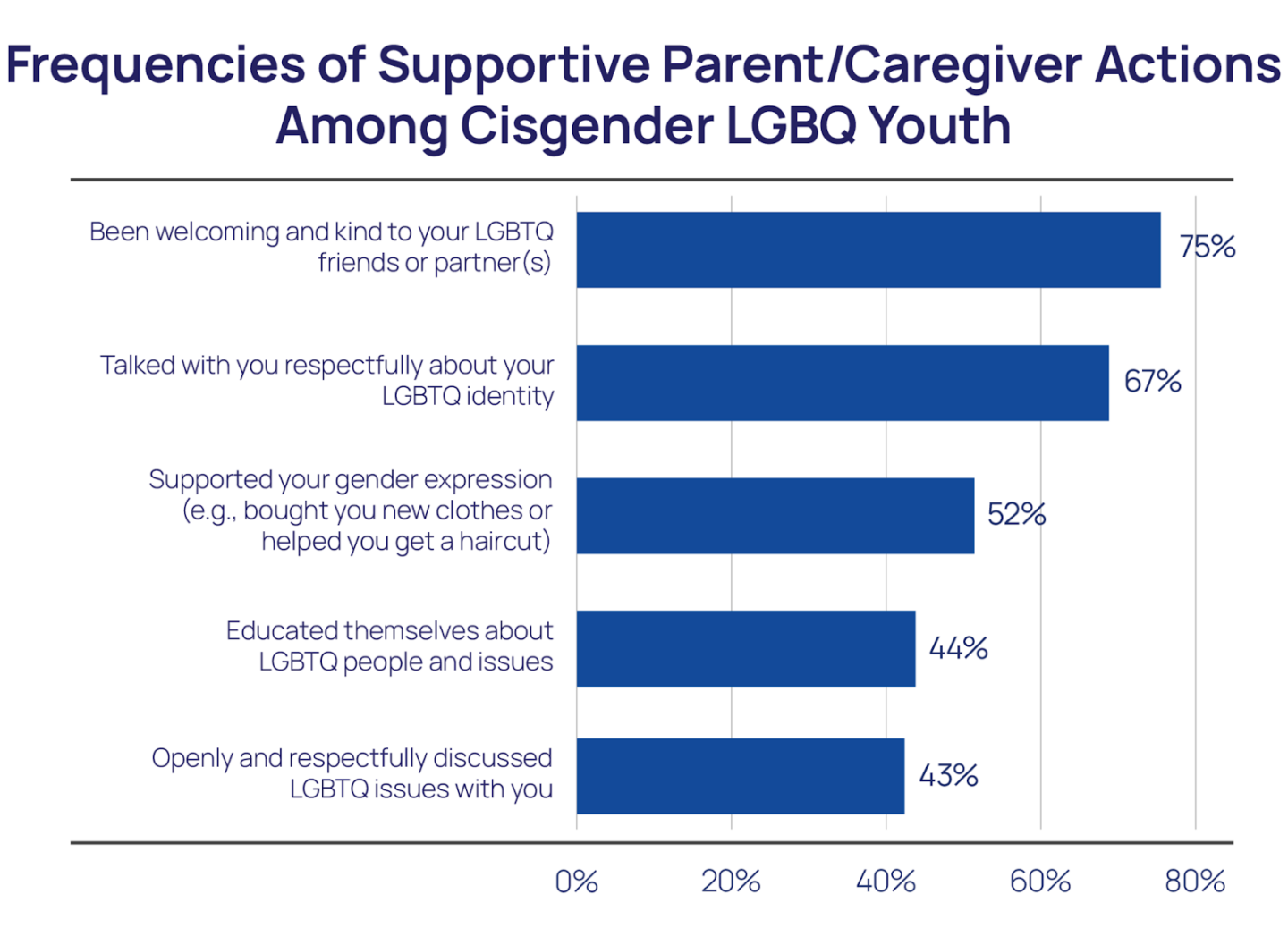

The most common accepting behavior among parents and caregivers was being welcoming and kind to LGBTQ youths’ friends or partner(s). Among cisgender LGBQ youth, the five most frequently cited supportive actions taken by parents or caregivers were: 1) being welcoming and kind to youths’ LGBTQ friends or partner(s) (75%), 2) talking with youth respectfully about their LGBTQ identity (67%), 3) supporting youths’ gender expression (52%), 4) educating themselves about LGBTQ people and issues (43%), and 5) openly and respectfully discussing LGBTQ issues with youth (43%).

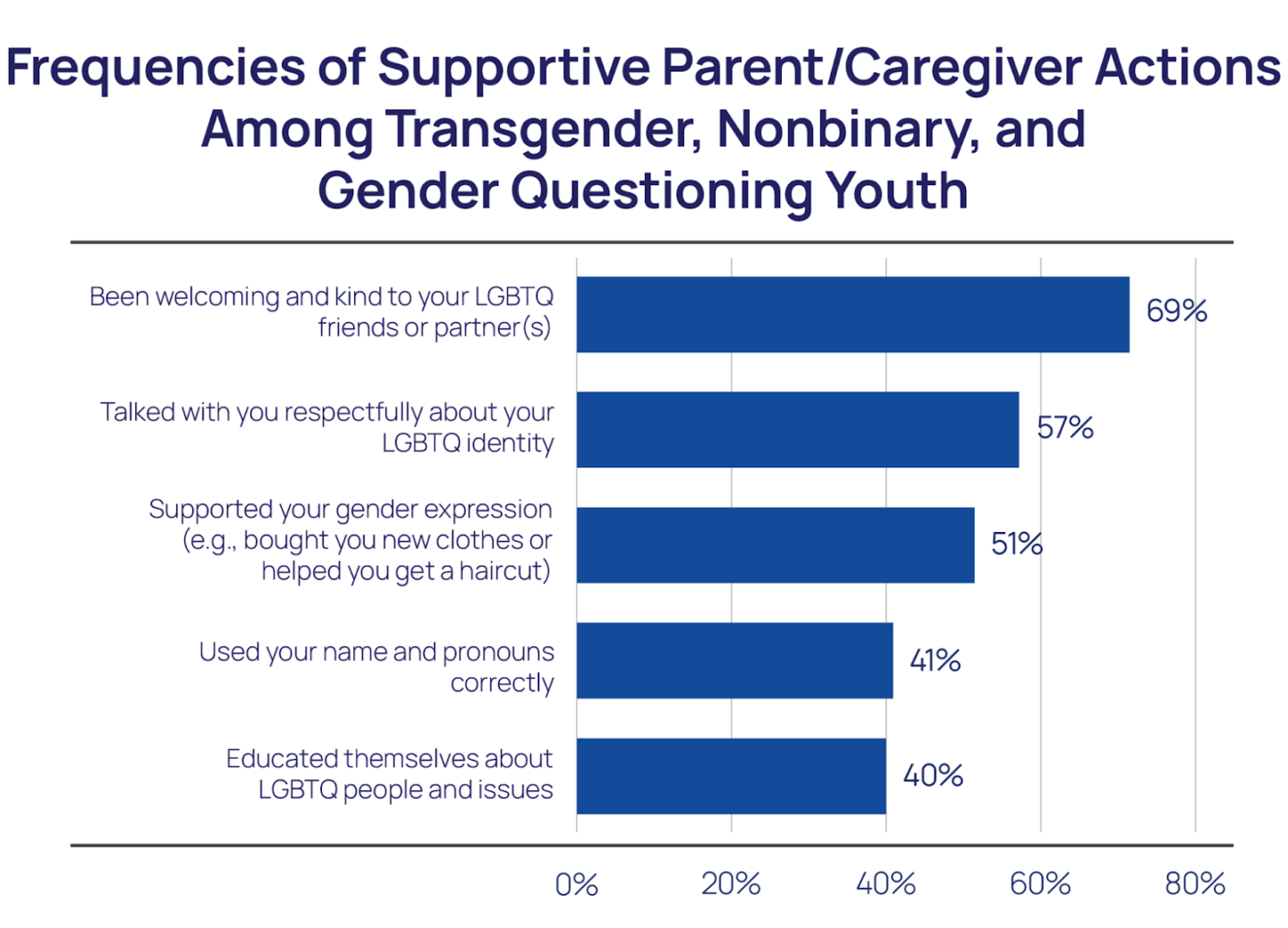

Among transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth, the five most frequently cited supportive actions taken by parents or caregivers were: 1) being welcoming and kind to youths’ LGBTQ friends or partner(s) (69%), 2) talking with youth respectfully about their LGBTQ identity (57%), 3) supporting youths’ gender expression (51%), 4) using youths’ name and pronouns correctly (40%), and 5) educating themselves about LGBTQ people and issues (40%).

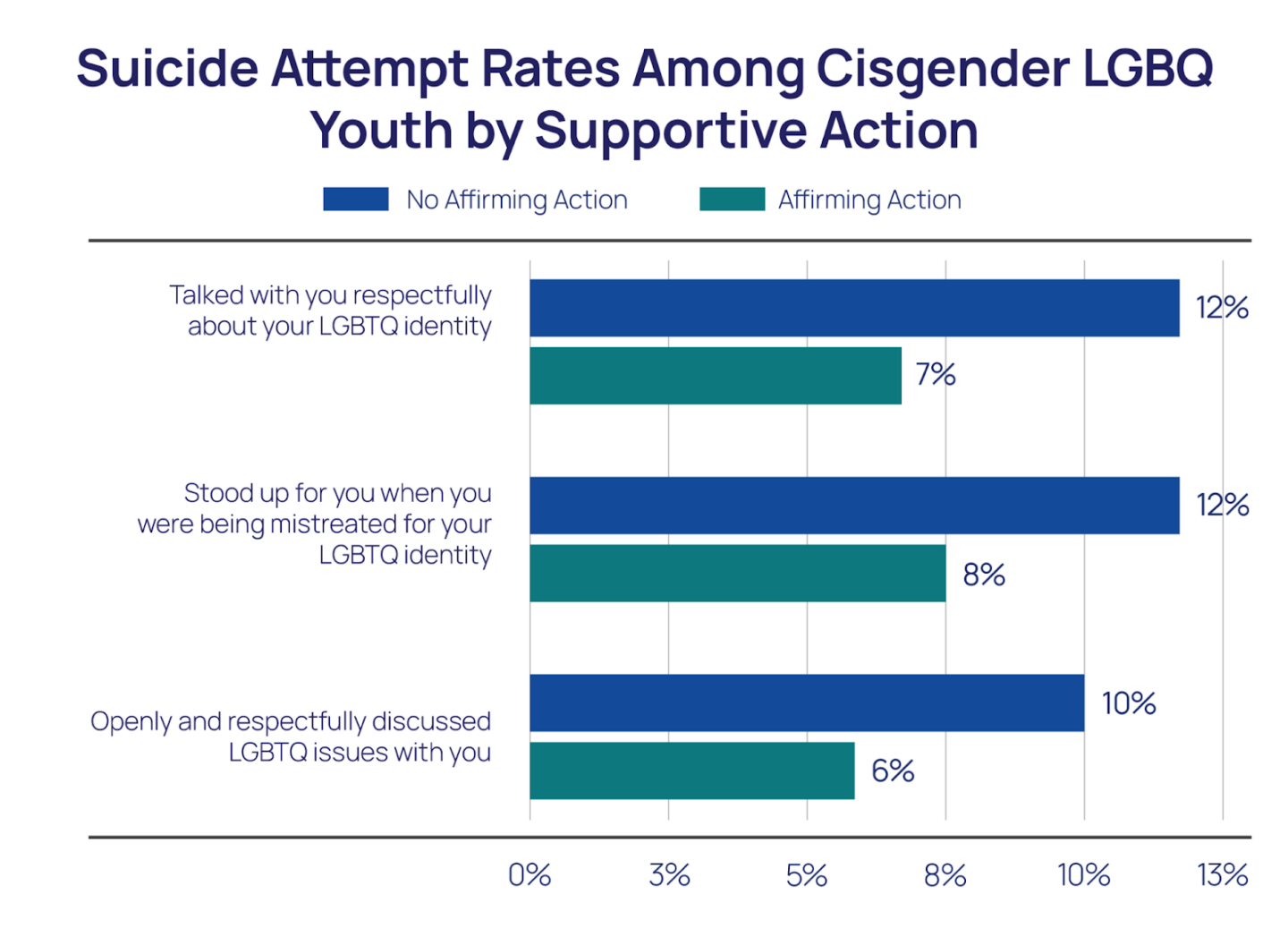

Supportive actions taken by parents and caregivers were associated with lower suicide risk among LGBTQ youth. For cisgender LGBQ youth, eight of the eleven supportive actions relevant to cisgender youth were significantly associated with lower odds of a suicide attempt in the past year, ranging from 47% to 25% lower odds. The three supportive actions associated with the lowest odds of attempting suicide in the past year were talking with youth respectfully about their LGBTQ identity (aOR = 0.54), openly and respectfully discussing LGBTQ issues with youth (aOR = 0.58), and standing up for youth when they were being mistreated due to their LGBTQ identity (aOR = 0.58), which were all associated with more than 40% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year among cisgender LGBQ youth. The three actions not associated with lower suicide risk among cisgender LGBQ youth were: encouraging other family members or friends to respect youths’ LGBTQ identity, finding a faith community that affirms and respects youths’ LGBTQ identity, and connecting youth with adult LGBTQ people as mentors or role models.

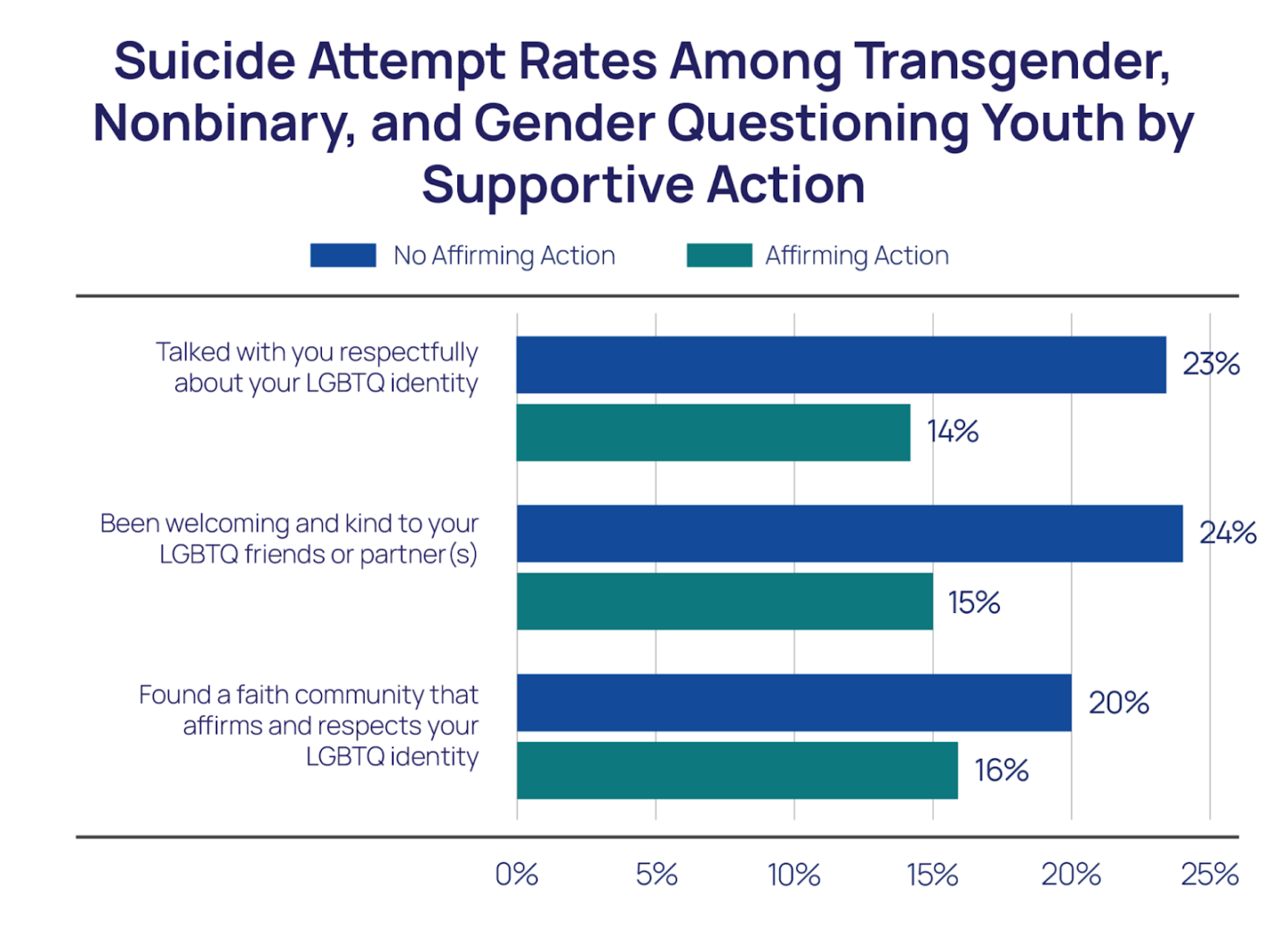

For transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth, eleven of the twelve supportive actions were significantly associated with lower odds of a suicide attempt in the past year, ranging from 42% to 16% lower odds. The three supportive actions associated with the lowest odds of attempting suicide in the past year among transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth were talking with youth respectfully about their LGBTQ identity (aOR = 0.59), being welcoming and kind to youths’ LGBTQ friends or partner(s) (aOR = 0.61), and finding a faith community that affirms and respects youths’ LGBTQ identity (aOR = 0.64). Talking with transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth respectfully about their LGBTQ identity was associated with just over 40% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year, and both being welcoming and kind to youths’ LGBTQ friends or partner(s) and finding a faith community that affirms and respects youths’ LGBTQ identity were associated with more than 30% decreased odds of attempting suicide in the past year. The action not associated with lower suicide risk among transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth was connecting youth with adult LGBTQ people as mentors or role models.

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2021 of 33,993 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. Using supportive actions identified by the Family Acceptance Project, survey respondents were asked, “Have your parents or guardians ever taken any of the following actions to support your LGBTQ identity? Please select any that apply,” with the following options: 1) Supported your gender expression, 2) Talked with you respectfully about your LGBTQ identity, 3) Encouraged other family members or friends to respect your LGBTQ identity, 4) Asked you how you would like your LGBTQ identity to be discussed with other people, 5) Been welcoming and kind to your LGBTQ friends or partner(s), 6) Took you to LGBTQ-related events or celebrations, 7) Used your name and pronouns correctly, 8) Found a faith community that affirms and respects your LGBTQ identity, 9) Connected you with adult LGBTQ people as mentors or role models, 10) Stood up for you when you were being mistreated due to your LGBTQ identity, 11) Educated themselves about LGBTQ people and issues, and 12) Openly and respectfully discussed LGBTQ issues with you. One action related to using names and pronouns correctly pertains primarily to transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth, therefore results for this item were confined to those youth. Respondents were excluded from analyses if they reported that they were not out to their parents. Our item on attempting suicide in the past 12 months was taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Adjusted logistic regression models were conducted to determine the association between each supportive action and a past-year suicide attempt while controlling for age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual identity, and census region.

Looking Ahead

These findings highlight the important role that parents and caregivers play in the mental health of LGBTQ youth. While some parents’ and caregivers’ supportive actions — such as being welcoming to youths’ LGBTQ friends and partner(s) — were commonly reported in the sample, the average frequency across all twelve supportive actions was 40% for cisgender LGBQ youth and 36% for transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth. Rates for all but one supportive action were lower for transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth compared to cisgender LGBQ youth, suggesting that parents and caregivers of transgender, nonbinary, or gender questioning youth may be less equipped or more resistant to affirming their child’s identity. Transgender, nonbinary, or gender questioning youth reported higher rates of their parents or caregivers taking them to LGBTQ-related events or celebrations compared to their cisgender LGBQ peers, which may be indicative of families of transgender, nonbinary, or gender questioning youth being more proactive about finding support groups or community for their children.

Our data also show significant associations between parents’ and caregivers’ supportive actions and lower suicide risk. For both cisgender LGBQ and transgender, nonbinary, and gender questioning youth, a majority of these supportive actions were associated with lower odds of a suicide attempt in the past year. For example, talking with youth respectfully about their LGBTQ identity, which can look like asking open-ended questions about identity labels or pronouns that youth use, asking for clarity about what their identity means to them, or asking them about their experiences with anti-LGBTQ discrimination, was associated with over 40% lower odds of a suicide attempt in the past year among all LGBTQ youth. These findings highlight the fact that a wide variety of supportive actions are associated with lower LGBTQ youths’ suicide risk.

There is a need for more education for parents and caregivers of LGBTQ youth, both about the positive impacts of supporting their child’s LGBTQ identity and about how to take supportive actions. The Trevor Project’s Resource Center, which includes guides such as “How to Support Bisexual Youth” and “A Guide to Being an Ally to Transgender and Nonbinary Youth,” offers a variety of resources for parents and caregivers who want to learn more about how to support their LGBTQ child. LGBTQ organizations should partner with parents and caregivers of LGBTQ youth and provide training on how best to support their child’s LGBTQ identity. Training topics suggested by these findings include how to discuss LGBTQ identity with your child, where to find education about LGBTQ identities and issues, and how to stand up for your LGBTQ child. Such training should be offered in a variety of languages and cultural settings and should be accessible to low-income families or parents with disabilities to ensure accessibility and inclusion. The Family Acceptance Project is also a good resource for organizations working with parents and caregivers of LGBTQ youth.

The Trevor Project is dedicated to supporting a world where LGBTQ youth can thrive. Our public education team offers training on LGBTQ allyship and suicide prevention to a variety of youth-facing organizations, including child welfare and foster care agencies. Our 24/7 crisis services are available in three different modalities – phone, chat, and text – so that youth in crisis have multiple avenues to communicate with culturally competent and affirming counselors. Our TrevorSpace platform also connects youth with supportive peers. Further, Trevor’s research and advocacy teams are focused on using data to advance LGBTQ-inclusive policies and practices and empower youth-serving professionals with the knowledge necessary to understand and address these young people’s mental health needs.

References

- Bouris, A., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Pickard, A., Shiu, C., Loosier, P. S., Dittus, P., Gloppen, K., & Michael Waldmiller, J. (2010). A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(5), 273-309.

- Goldbach, J. T., & Gibbs, J. (2015). Strategies employed by sexual minority adolescents to cope with minority stress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 297.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697.

- Rostosky, S. S., & Riggle, E. D. (2017). Same-sex relationships and minority stress. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 29-38.

- Ryan, C., Russell, S. T., Huebner, D., Diaz, R., & Sanchez, J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(4), 205-213.

- Toomey, R. B. (2021). Advancing research on minority stress and resilience in trans children and adolescents in the 21st century. Child Development Perspectives, 15(2), 96-102.

For more information, please contact: [email protected]