EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Not all youth currently have access to high-quality and culturally appropriate mental health care. Unfortunately, youth who experience the greatest mental health disparities, including youth living in poverty (Hodgkinson et al., 2017), youth of color (Alegria et al., 2010), and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth (Steele et al., 2017; Williams & Chapman et al., 2012), are more likely to have unmet mental health care needs. Higher rates of mental health challenges and lower rates of access to care among youth with the most need reflect the impact of discrimination, victimization, and oppression at the interpersonal, community, and structural levels.

COVID-19 has highlighted vast disparities that exist within the U.S. mental health care system (Auerbach & Miller, 2020). For marginalized communities, COVID-19 exacerbates structural inequalities that already exist, particularly among those at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities (Bowleg, 2020). COVID-19 has negative impacts on not only physical health, but also mental health through increased isolation, economic strain, and anxiety which are expected to be experienced at greater levels among marginalized youth (Green, Price-Feeney, & Dorison, 2020). However, widespread recognition of a broken system can serve as an entry point towards improving the ways care is provided.

A greater understanding of barriers to mental health care can help shape policies and practices that produce a system of care capable of meeting the needs of all youth. Using data from a large, diverse national sample of LGBTQ youth between the ages of 13–24 in the United States, this paper highlights disparities in receipt of desired mental health care as well as LGBTQ youth perceptions of barriers to receiving mental health care, including how these barriers operate within and across social identities. Drawing on this data and examples of healthcare transformations that have occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, we offer recommendations for ways to address barriers to quality mental health care for LGBTQ youth

Overall, more than half (54%) of LGBTQ youth who reported wanting mental health care in the past year did not receive it. Statistically significant within-group differences were found, with Black (62%), Latinx (62%), and Asian American (60%) LGBTQ youth reporting higher levels of not receiving desired mental health care compared to LGBTQ youth who were White (53%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (53%), or multiple race/ethnicities (55%). Cisgender LGBQ youth had greater reports of unmet mental health care needs (57%) compared to transgender and nonbinary youth (50%). LGBTQ youth who lived in the South reported the highest levels of unmet mental health care needs (58%), while LGBTQ youth in the Northeast reported the lowest levels (47%).

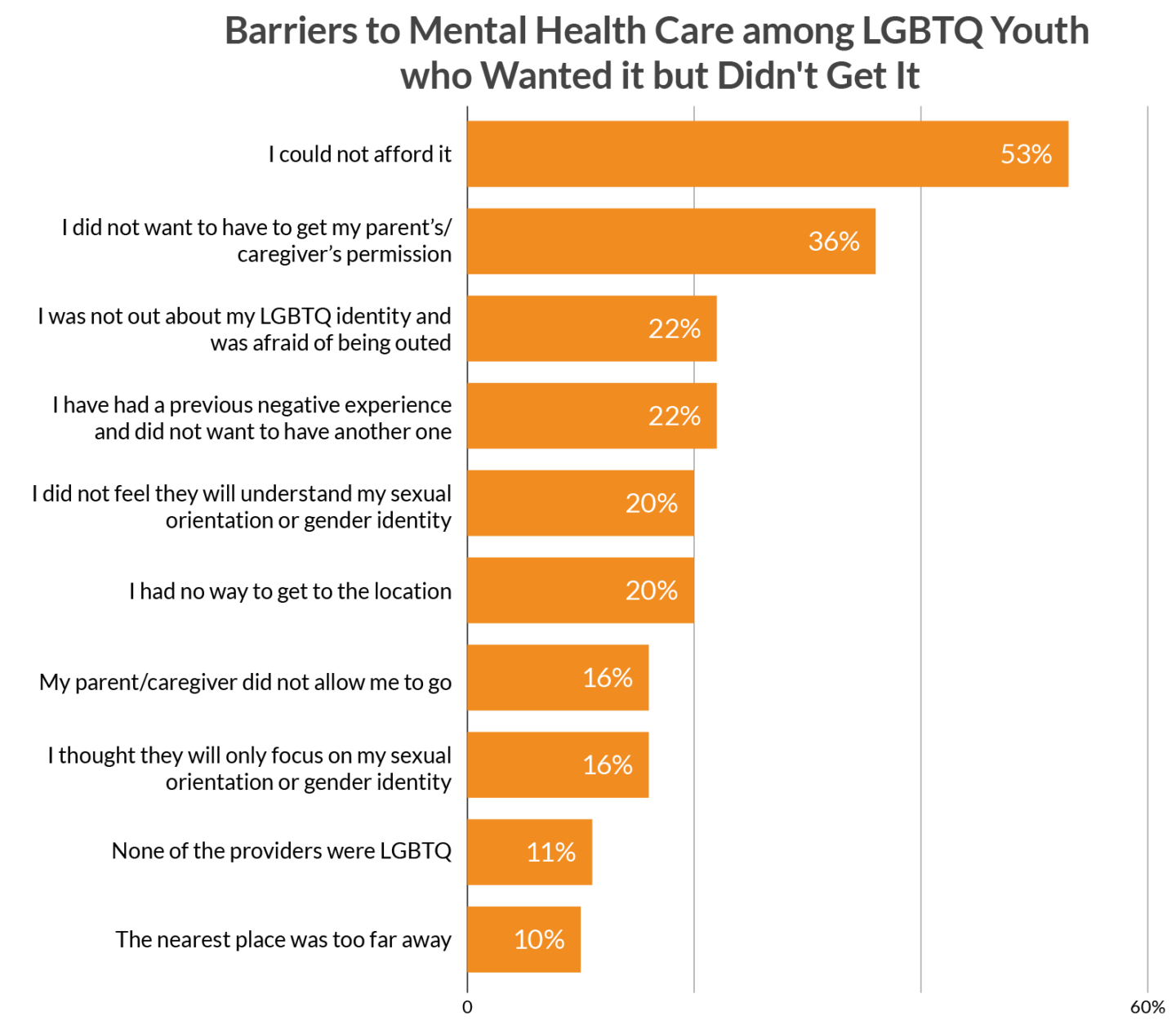

LGBTQ youth endorsed a variety of barriers related to the reasons they were unable to receive the mental health care they wanted in the past year. Inability to afford care was the most frequently endorsed barrier (53%) to not receiving desired mental health care among all LGBTQ youth. Over one-third of LGBTQ youth reported concerns due to not wanting to get parental permission needed to receive care, including half of Asian American/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth. American Indian/Alaskan Native LGBTQ youth were more concerned that a provider would only focus on their sexual orientation or gender identity (29%) compared to LGBTQ youth overall (16%). One in three transgender and nonbinary youth stated that they didn’t receive desired mental health care because they didn’t feel a provider would understand their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Over 3,500 LGBTQ youth provided written descriptions detailing additional reasons they were not able to receive the mental health care they desired. LGBTQ youth of color highlighted concerns related to mental health stigma within their culture as well as a mental health care system that wasn’t equipped to understand their racial and ethnic identities. Youth frequently described stigma using words like “embarrassed,” “ashamed,” and “weakness” for why they didn’t get mental health care despite wanting it. LGBTQ youth reported concerns about the ability to trust therapists, particularly related to conversion efforts and disclosing information to family members.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been increased national conversations focused on mental health, making now a crucial time to implement needed changes. For example, COVID-19 has highlighted that mental health care can be effectively provided via telephone or video conferencing when necessary. The mental health care system in the U.S. must adapt to the needs of those who are unable to find appropriate mental health care locally by expanding tele-mental health. Further, during COVID-19, policy changes on parity in reimbursement rates for tele-mental health care and allowing for the provision of out-of-state care through tele-mental health have expanded the ability for those in need to receive care. Such changes should be instantiated and expanded on in the future. There is also a need for public health campaigns that raise awareness of ways to reduce mental health stigma and assist in helping youth find ways to ask for help. Additionally, the mental health workforce needs to engage in ongoing professional development around anti-racism as well as addressing LGBTQ-stigma and the impact both have on mental health. Addressing barriers will require an approach that relies on policy and funding changes as well as changes to the ways mental health care providers serve those who are in need of care. We hope others will join us in finding solutions that provide LGBTQ youth with the support they need to thrive.

Methodology Summary

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data using an online survey platform between December 2, 2019 and March 31, 2020. An analytic sample of 40,001 youth ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. Youth were asked, “In the past 12 months, have you wanted psychological or emotional counseling from a mental health professional?” with response options of “no,” “yes, but I didn’t get it” and “yes, and I got it.” LGBTQ youth who selected, “yes, but I didn’t get it,” were asked to select which, from a list of ten potential barriers to mental health care, applied to them. Additionally, youth were able to provide text responses about any additional barriers they faced.

BACKGROUND

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth face large disparities in suicide risk compared to their non-LGBTQ peers. Research has documented that LGBTQ youth report significantly higher rates of having seriously considered suicide, making a plan to attempt suicide, and attempting suicide compared to heterosexual and/or cisgender youth (Kann et al., 2018; Johns et al., 2019). Increased suicide risk among LGBTQ youth is due to minority stress including discrimination, victimization, and rejection associated with being in a socially stigmatized position in society (Meyer, 2003), as opposed to being LGBTQ in and of itself.

Minority stress may be the most persistent and problematic for individuals who occupy multiple marginalized social positions (Cyrus, 2017). For example, within the LGBTQ community, individuals who are bisexual and those who are transgender and nonbinary report the highest rates of suicide attempts, reflecting increased exposure to minority stress (Price-Feeney, Green, & Dorison, 2020; Salway et al., 2019). LGBTQ youth of color also have multiple marginalized identities and experiences to contend with, as do those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged (Hoffman et al., 2020). In the broader U.S. population, suicide is historically higher among White and American Indian/Alaskan Native youth (Sullivan et al., 2015), but recent studies highlight rising rates among Black youth (Bridge et al., 2019; Lindsay et al., 2019). Thus, there is a continued need to take an intersectional approach to address suicide and mental health care among LGBTQ youth. Researchers must work to better understand the experiences and needs of LGBTQ youth who hold multiple marginalized identities in order to best address practices and policies to improve the well-being of LGBTQ youth and prevent suicide.

Not all youth currently have access to high-quality and culturally appropriate mental health care. Unfortunately, youth who experience the greatest mental health disparities, including youth living in poverty (Hodgkinson et al., 2017); Black, Indigenous, and other youth of color (Alegria et al., 2010); and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth (Steele et al., 2017; Williams & Chapman et al., 2012), are more likely to have unmet mental health care needs. Higher rates of mental health symptoms and suicide attempts coupled with lower rates of access to care further reflect the impact of discrimination, victimization, and oppression at the interpersonal, community, and structural levels. A greater understanding of barriers to mental health care experienced by diverse groups of LGBTQ youth can serve to inform system improvements and transformations.

COVID-19 has highlighted vast disparities that exist within the U.S. mental health care system (Auerbach & Miller, 2020). However, widespread recognition of a broken system can serve as an entry point towards improving the way care is provided. During the COVID-19 pandemic, much of the national conversation has turned to focus on mental health and suicide risk, as COVID-19 has negative impacts on not only physical health, but also mental health through increased isolation, economic strain, and anxiety (Green, Price-Feeney, & Dorison, 2020). For marginalized communities, COVID-19 exacerbates structural inequalities that already exist, particularly among those at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities (Bowleg, 2020).

A greater understanding of barriers to mental health care can help shape policies and practices that produce a system of care capable of meeting the needs of all youth. Using data from a large, diverse national sample of LGBTQ youth between the ages of 13–24 in the United States, this white paper takes an intersectional lens towards unmet mental health care needs among LGBTQ youth. We describe disparities in receipt of mental health care as well as LGBTQ youth perceptions of barriers to receiving desired mental health care, including how these barriers operate within and across marginalized identities. Drawing on this data and from examples of healthcare transformations that have occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, we offer recommendations for ways to address barriers to quality mental health care for all LGBTQ youth.

METHODOLOGY

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data using an online survey platform between December 2, 2019, and March 31, 2020. A sample of individuals ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. The final analytic sample consisted of 40,001 LGBTQ youth, with representation from over 4,000 Hispanic/Latinx LGBTQ youth, over 1,500 Black/African American LGBTQ youth, over 1,500 Asian/ Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth, and over 500 American Indian/Alaskan Native LGBTQ youth. Further, nearly 15% of the sample reported that they struggled financially to meet their basic needs. All youth were asked, “In the past 12 months, have you wanted psychological or emotional counseling from a mental health professional?” with response options of “no,” “yes, but I didn’t get it,” and “yes, and I got it.” For the purposes of the current study, youth who responded “yes, but I didn’t get it” are considered as having unmet mental health care needs. These youth were asked which barriers, from a list of ten potential barriers to mental health care, applied to them. Youth were also able to provide text responses about any additional barriers they faced. Quantitative data on mental health care access and barriers were analyzed for the overall sample and segmented based on sexual orientation, gender identity, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and age. Qualitative responses were reviewed to highlight additional prominent themes not fully accounted for in the quantitative data.

RESULTS

Unmet Mental Health Care Needs among LGBTQ Youth

The majority of LGBTQ youth (84%), reported wanting counseling from a mental health care professional in the past year; however, strikingly more than half of those who wanted it (54%) did not receive it. The LGBTQ youth in our sample span a wide range of social identities beyond being a member of the LGBTQ community. In an adjusted logistic regression model (See Table 1), race/ethnicity, gender, geography, and socioeconomic status were all significant predictors of whether or not an LGBTQ youth received the mental health care they desired. More specifically, in our adjusted model Latinx and Asian American/Pacific Islander youth were approximately 40% more likely and Black youth nearly 30% more likely to have unmet mental health care needs compared to non-Hispanic White LGBTQ youth. Further, youth who resided in the Southern region of the U.S. were over 50% more likely to have unmet mental health care needs compared to those in the Northeast, with those in the Midwest and West over a third more likely. Youth who had trouble meeting basic needs were approximately 30% more likely to have unmet mental health care needs compared to those who could afford to meet basic needs. Youth assigned female at birth and transgender and nonbinary youth were nearly 25% more likely to receive desired mental health care compared to youth assigned male at birth and cisgender LGBQ youth, respectively. Levels of unmet mental health care were comparable across sexual orientations and by age. Below, we outline additional insights on unmet mental health care needs by race/ethnicity, gender identity, geography, and socioeconomic status.

Table 1. Identity Characteristics Associated with Not Receiving Desired Mental Health Care

| aOR | |

| Ages 18–24 (13–17 as reference) | 0.95 |

| Trouble meeting basic needs | 1.28 |

| Transgender and nonbinary (cisgender as reference) | 0.71 |

| Assigned female at birth | 0.72 |

| Sexual orientation (gay/lesbian as reference) | |

| Straight | 0.79 |

| Bisexual | 0.97 |

| Queer | 0.90 |

| Pansexual | 1.06 |

| Questioning | 1.05 |

| Region (Northeast as reference) | |

| South | 1.53 |

| Midwest | 1.35 |

| West | 1.38 |

| Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White as reference) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.94 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 1.38 |

| Black/African American | 1.29 |

| Latinx | 1.42 |

| Multiple race/ethnicities | 1.08 |

| Bolded identities are significant at p<.001 |

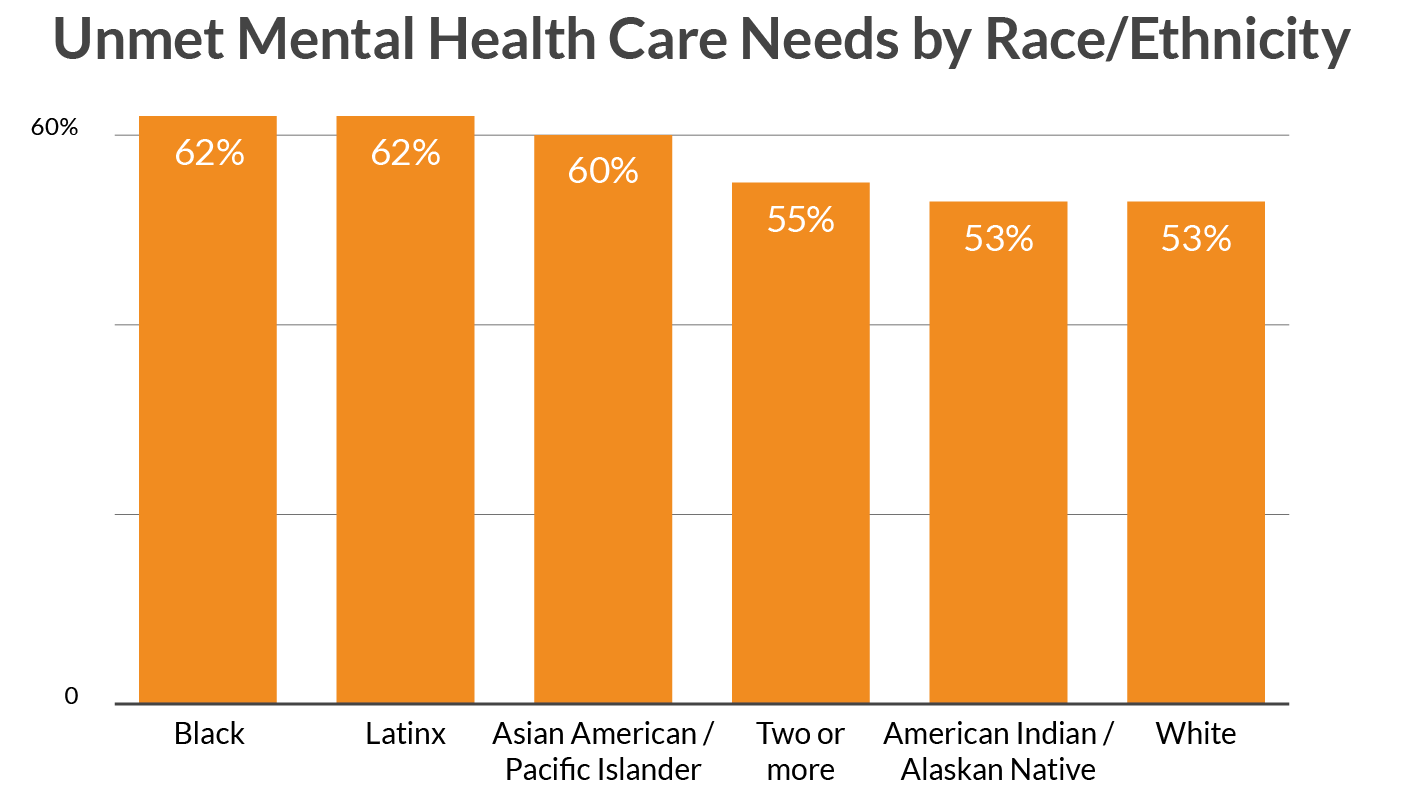

Race/Ethnicity

Black (62%), Latinx (62%), and Asian American/Pacific Islander (60%) LGBTQ youth reported significantly higher levels of not receiving the mental health care they desired than LGBTQ youth who were White (53%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (53%), or multiple race/ethnicities (55%).

Figure 1. Unmet Mental Health Care Needs by Race/Ethnicity

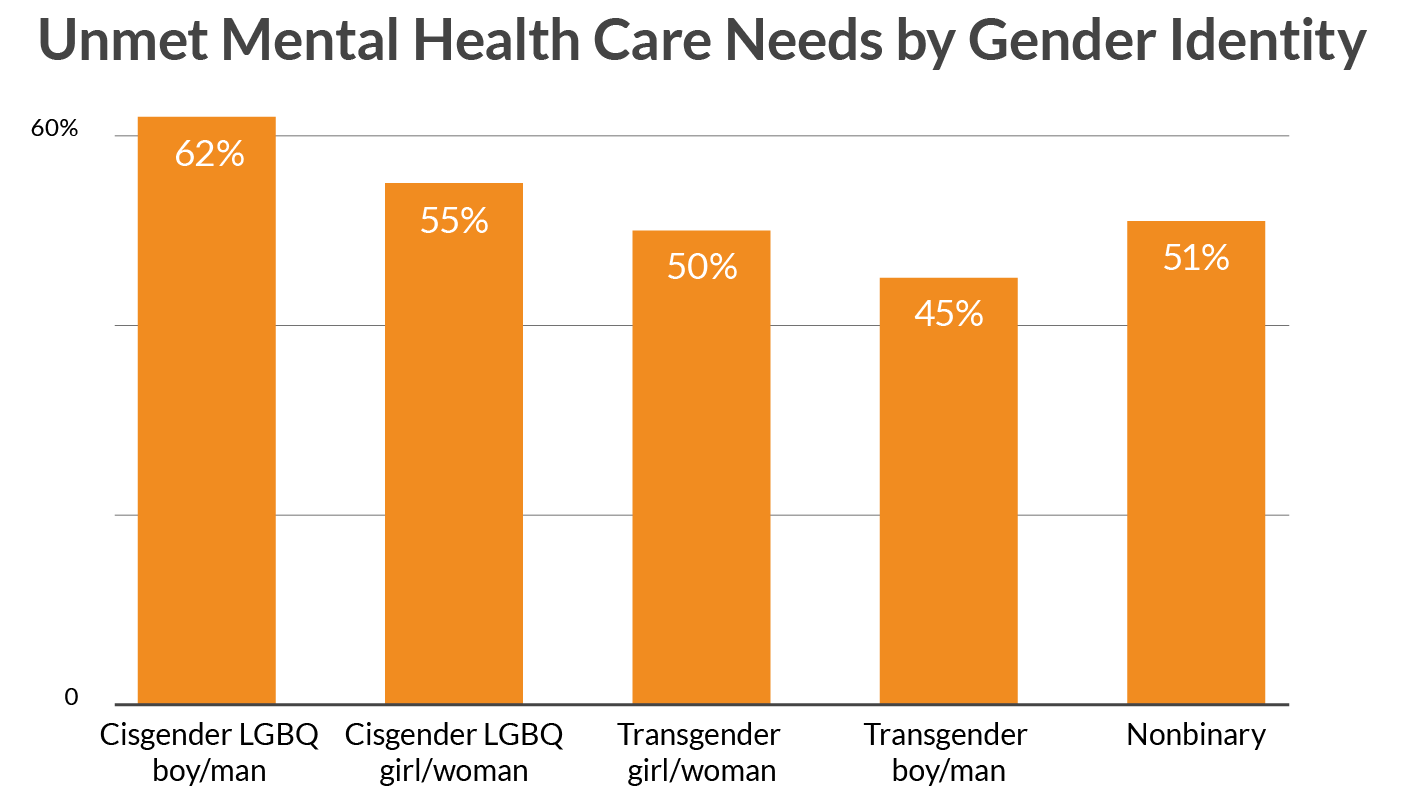

Gender Identity

Cisgender LGBQ youth (57%) had greater reports of unmet mental health care needs compared to transgender and nonbinary youth (50%). Cisgender LGBQ youth reporting greater rates of unmet mental health care needs compared to transgender and nonbinary youth was consistent across race/ethnicity. Cisgender LGBQ males reported the highest rates of unmet mental health care needs by gender identity, with 62% reporting that they wanted it but didn’t get it. This finding was particularly strong for Latinx cisgender LGBQ males, with 72% of those who reported wanting mental health care in the past year, not receiving it. Transgender boys/transgender men were most likely to receive desired mental health care. Increased rates of obtaining desired mental health care among transgender and nonbinary youth compared to cisgender LGBQ youth is likely related to the recommended role of mental health professionals as part of the standard of care in the transitioning process (Coleman et al., 2012).

Figure 2. Unmet Mental Health Care Needs by Gender Identity

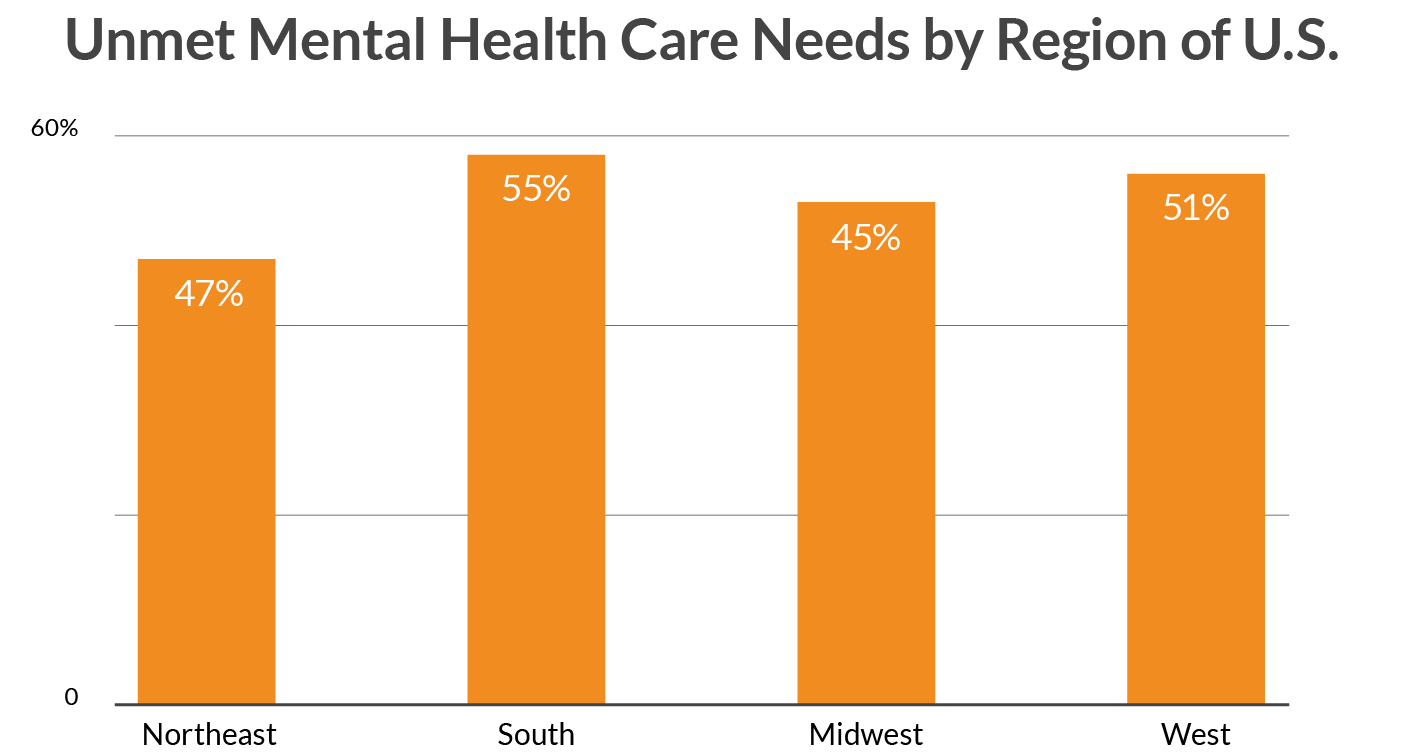

Geography

LGBTQ youth who lived in the South (58%), West, (56%), and Midwest (53%) regions of the U.S. reported higher levels of unmet mental health care needs than those in the Northeast (47%).

Figure 3. Unmet Mental Health Care Needs by Region of U.S.

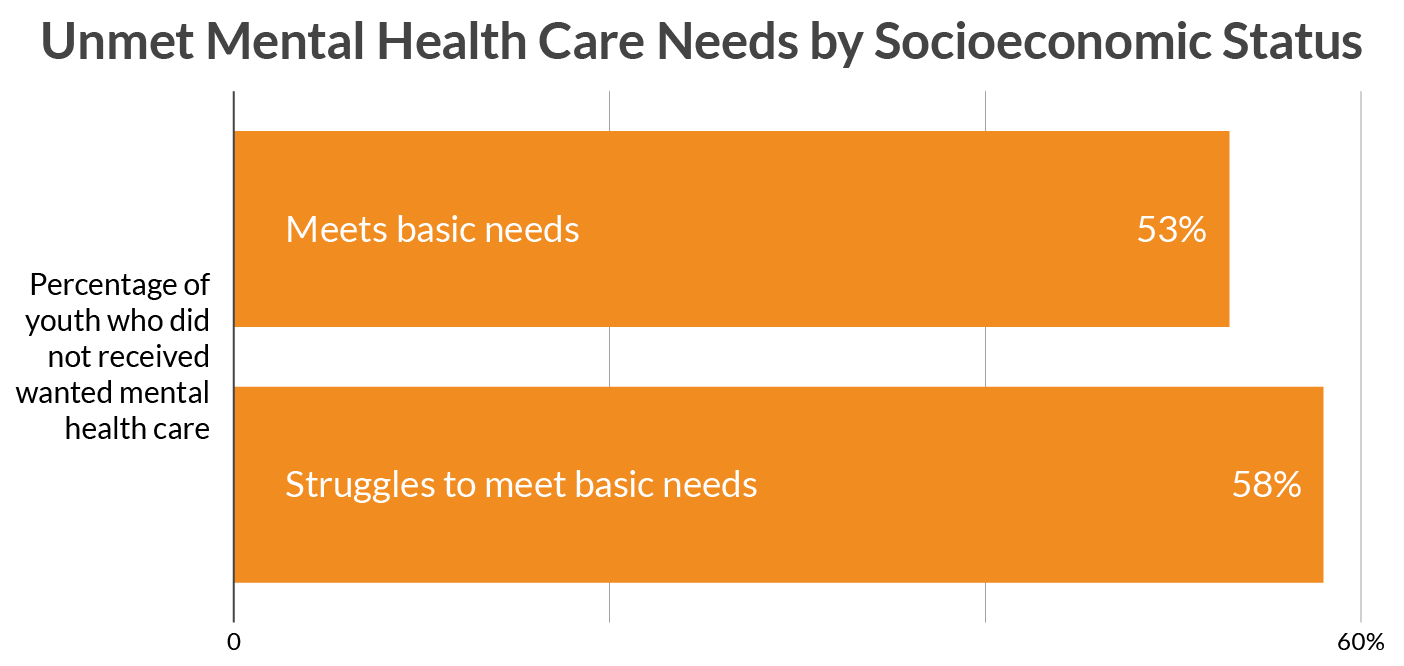

Socioeconomic status

Greater reports of unmet mental health care needs were found among youth who reported that they or their families were struggling financially to meet their basic needs (58%) compared to those who were at least able to meet basic needs (53%). Although those who reported struggling to meet basic needs were significantly more likely to have unmet needs compared to those who were able to meet basic needs, both groups had high levels of unmet mental health care needs stemming from the existing high costs of mental health care in the United States.

Figure 4. Unmet Mental Health Care Needs by Socioeconomic Status

Barriers to Receiving Mental Health Care among LGBTQ Youth

Based on our quantitative survey data, the most commonly endorsed barrier was inability to afford care (53%). Other universal barriers include previous negative experiences (22%) as well as transportation concerns, such as having no way to get to the location (20%) or having the location be too far away (10%). Youth-specific concerns relating to not wanting to get parental permission (36%) and having parents who refused to allow care (16%) were also endorsed by LGBTQ youth. LGBTQ-specific barriers included concerns around being outed (22%), not having their LGBTQ identity understood (20%) or overly focusing on their LGBTQ identity (16%), and not finding a provider who was LGBTQ (11%).

Figure 5. Barriers to Mental Health Care among LGBTQ Youth who Wanted it but Didn’t Get It

Barriers by Race/Ethnicity

In general, youth of color reported comparable levels of the list of ten barriers to other LGBTQ youth. However, there were notable exceptions. Black LGBTQ (11%), Asian American/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth (15%), and Latinx LGBTQ youth (18%) endorsed not receiving mental health care due to a previous negative experience at lower rates compared to LGBTQ youth overall (22%). However, this data likely reflects a lower probability of these youth receiving any mental health care in the past or a tendency for youth of color to have lower expectations of mental health providers. Asian American/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth endorsed lower rates of not being able to afford care (42%) compared to the overall sample (53%). However, Asian American/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth reported greater levels of barriers related to parents, including not wanting to get parental permission (50% compared to 36% among LGBTQ youth overall) and parents not allowing them to go to therapy (21% compared to 16% among LGBTQ youth overall). Both Asian American/Pacific Islander (28%) and Latinx LGBTQ youth (25%) had greater rates of endorsing not wanting to be outed about their LGBTQ identity as a barrier compared to the overall sample (22%). American Indian/Alaskan Native LGBTQ youth endorsed greater levels of concerns that none of the available providers were LGBTQ (20%) compared to the overall sample (11%). American Indian/Alaskan Native LGBTQ youth were also more concerned that a provider would only focus on their sexual orientation or gender identity (29%) compared to LGBTQ youth overall (16%).

Barriers by Gender Identity

Despite having lower rates of unmet mental health care needs, likely due in part to the inclusion of mental health treatment in the standards of care for transitioning, transgender and nonbinary youth endorsed higher levels of many barriers compared to their cisgender LGBQ peers. Barriers related to the LGBTQ competence of providers were of particular concern to transgender and nonbinary youth. Fears that a provider would not understand the youth’s sexual orientation or gender identity were reported by 33% of transgender and nonbinary youth compared to 13% of cisgender LGBQ youth. Similarly, transgender and nonbinary youth (17%) endorsed none of the providers being LGBTQ as a barrier more often than cisgender LGBQ youth (7%) as well as greater concerns about being outed about their LGBTQ identity (26%) compared to cisgender LGBQ youth (20%). Additionally, 21% of transgender and nonbinary youth were concerned that a mental health care provider would only focus on their LGBTQ identity compared to 12% of cisgender LGBQ youth. Transgender and nonbinary youth also expressed more concerns based on negative mental health care experiences in the past (26%) compared to cisgender LGBQ youth (20%). Cost was also a greater concern, with 58% of transgender and nonbinary youth endorsing concerns around being able to afford care compared to 50% of cisgender LGBQ youth. Within transgender and nonbinary identities, transgender girls/women (33%) and youth who were questioning their gender identity (30%) endorsed fears about being outed based on their LGBTQ identity as a barrier to receiving wanted mental health care more often than nonbinary youth (25%) and transgender boys/men (26%). Additionally, transgender girls/women (27%) were most concerned about a mental health provider only focusing on their LGBTQ identity compared to transgender boys/men (23%), nonbinary youth (21%), and youth questioning their gender (17%).

Many of these LGBTQ-specific barriers were expanded upon in optional written responses in addition to other salient themes around barriers to mental health. Below we detail prominent themes from the written responses of over 3,500 LGBTQ youth who endorsed the option of “another reason” from the list of provided barriers.

Barriers by Geography

Ability to afford care was one of the most prominent differences across the regions with 45% of LGBTQ youth in the Northeast reporting ability to afford care as a barrier compared to 55% in the South, 53% in the Midwest, and 53% in the West. Not receiving wanted care due to fears about being outed was also higher in the South (23%), Midwest (22%), and West (22%) compared to the Northeast (19%), as was not receiving care due to concerns that the provider would not understand the youth’s sexual orientation or gender identity, which was reported as a barrier by 17% of LGBTQ youth in the Northeast compared to 21% in the South and 20% in both the Midwest and West.

Barriers by Socioeconomic Status

Not surprisingly, 76% of youth who struggled to meet basic needs reported the ability to afford care as a barrier compared to 50% of those who could meet their basic needs. Additionally, LGBTQ youth who struggled to meet basic needs reported greater rates of barriers related to transportation such as the nearest place being too far away (16% vs. 9%) and having no way to get to the location (32% vs. 18%). A higher proportion of youth who struggled to meet basic needs also reported concerns related to a provider understanding their sexual orientation or gender identity (24% vs. 18%), and relatedly, that no providers were LGBTQ (15% vs. 10%).

LGBTQ Youth Descriptions of Barriers to Care

LGBTQ youth described universal barriers that are common to many individuals seeking mental health care as well as barriers specific to their status as members of the LGBTQ community and its intersection with other marginalized social identities. Below we discussed eleven themes expressed by youth in written responses.

Cultural Barriers to Care for Youth of Color

Black, Latinx, and Asian American/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth highlighted concerns related to mental health stigma within their culture as well as a mental health system that wasn’t equipped to understand their racial/ethnic identities. For example, one Black youth stated, “Stigma from the African American community is a big problem, and I don’t want to be looked at any differently by my family.” Similarly, one Latinx LGBTQ youth indicated, “Mental illness is ignored/frowned upon in Hispanic/Latino communities because of pride issues that are tied to families.” Asian American/Pacific Islander youth mentioned both “cultural stigma” and “racism” as reasons why they haven’t sought out care. LGBTQ youth of color also struggled with finding providers who understood their culture. For example, multiple Latinx LGBTQ youth believed that mental health care providers wouldn’t understand their culture with one saying, “no creí entenderian mi cultura,” while another stated, “I don’t feel as though a hetero White professional would be able to understand a queer person of color with strong roots in Latino culture.” Youth also expressed concern about the ability of predominantly White mental health care providers being able to understand the impact of racism on their mental health. As one youth stated, “Most of the mental healthcare providers in my area are White, and a lot of my anxieties are caused by living in a city plagued by racism and xenophobia. I don’t know that a white mental health professional would understand.” Additionally, in instances when culturally-grounded mental health care is available, it may be difficult to access as described by an American Indian youth who stated, “Free counseling is offered by the [Tribal] Nation, but there are three counselors for my entire county, so actually getting an appointment is rare.” Immigration issues were also among the concern of LGBTQ youth of color, including a Black LGBTQ youth who stated, “not enough immigrant black counselors,” and an Asian American/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth who stated, “It’s impossible trying to find someone covered by my insurance, let alone somebody who would understand being from an immigrant family.”

Concerns of LGBTQ Competence

Youth expressed a variety of concerns related to the challenges of finding an LGBTQ-affirming therapist. Some youth felt it was too hard to find care that affirmed both their LGBTQ identity and their religious beliefs such as a youth who said, “I’m both extremely religious and gay, and I won’t find anyone who can understand both at once,” and another youth who stated, “I wanted a Christian therapist, but feared I would get a crazy conversion therapist.” For other youth, they felt the only therapists they had access to were religious and, therefore, not appropriate for them. One youth stated, “I go to a religious school and I worry that if I use their counseling services I’ll be kicked out or that they’ll try to heal me with religion.” Other youth reported barriers related to previously harmful experiences concerning their LGBTQ identity. For example, one youth stated, “the last time I went to therapy, the counselor tried to get me away from my sexual orientation and said ‘gay was bad.’ It felt more of a conversion therapy more than help for my depression,” while another said, “My last counselor was very anti-LGBTQ and told me my depression would be cured if I had sex with a man.” Finding counselors that were equipped for specific mental health needs and LGBTQ-competent was also difficult for many youth, such as one youth who stated, “There are no providers in my area that cover both LGBTQ issues and issues for the rest of my mental health,” while another more specifically stated, “I want a professional who is trained to help people who both have autism and are LGBTQ, but I don’t think that kind of professional exists.”

Difficulties Accessing Gender-Affirming Care

Transgender and nonbinary youth frequently detailed the rarity of finding available mental health professionals who understand how to best support the mental health of transgender and nonbinary individuals. As one individual stated, “Every single therapist in my city that specifically knows how to counsel trans people does not take insurance and charges hundreds for one appointment, when I should be going weekly. The regular ‘LGBT therapists’ only know how to properly help LGB.” Others expressed previous bad experiences related to their gender identity such as a youth who said, “My mental health problems became so bad I cannot leave the house anymore to see a counselor. And the one I was previously seeing did not accept me as trans, because I am agender. She said I didn’t count as trans unless I wanted to be the opposite, so I also needed to find a new one.” Transgender youth also discussed fears of receiving therapy that didn’t respect their authentic identity and process of transitioning or not. This is evidenced by a youth who expressed, “I was scared that If I went to the wrong one, they would immediately put me on hormones without even checking to see if I 100% am transgender, but if I went to the Christian one my parents wanted I would have been shunned, ridiculed, or dismissed and probably would not have gotten help.” Fears of being outed were also expressed such as a youth who stated, “I have never asked for therapy but I want it. I’m afraid of being found out that I’m trans,” as well as one with concerns over having their identity recorded who stated, “Did not want being Trans on my medical and government medical record.”

Stigma and Shame

Youth frequently used words like “embarrassed,” “ashamed,” and “weakness” to describe their reasons for not getting mental health care despite wanting it. These feelings were particularly noted among youth who felt like their struggles weren’t as severe as others whom they knew needed therapy. For example, one youth stated, “Seeking therapy seems like a form of weakness because my life and my struggles, even with mental health, are not nearly as bad as a majority of the people around me. I go back and forth between believing I have a problem.” Similarly, another youth mentioned, “I didn’t think what I was going through was bad enough to warrant help. I was wrong.” Internalized stigma about help-seeking continues to hinder the ability of youth to obtain the care they need, evidenced by a youth who stated, “The fact that I have these thoughts is shameful to me. I wasn’t ready to get help. I still don’t think I am.” Other youth indicated how the negative values of others impacted their concerns about getting therapy such as “I was taught that needing therapy means you are weak,” “My family doesn’t see mental health as a problem, and I am ashamed,” and “The stigma of going to therapy would more or less oust me from my family.”

Depression- and Anxiety-Related Challenges to Help-Seeking

One of the more common themes centered on how existing anxiety and depression hinders youth ability to seek help. Examples of anxiety-related barriers included fears of making phone calls or leaving the house, fears about opening up to a stranger, feeling overwhelmed by trying to understand insurance policies, and fears of being rejected by a therapist for not having severe enough needs. As one youth stated, “A lot of anxiety, not being good at new situations with new people, and impostor syndrome telling me that I don’t really *need* help.” Other youth also detailed numerous concerns related to their anxiety such as one youth who reported experiencing, “anxiety about the entire process of having to look up my insurance provider, find someone in my area, talk to someone new, start a commitment, caregiver pay for the treatments, have my caregiver hold that over my head.” Despite the high rates of anxiety among LGBTQ youth and the effectiveness of evidence-based treatments for reducing anxiety, many youth found it to be the exact reason they were unable to receive treatment. As one youth aptly stated, “I was too anxious about my anxiety.” In addition to anxiety, symptoms related to depression were also noted as barriers to getting wanted mental health care. Multiple youth noted that the lack of motivation that accompanies their depression also makes it very hard for them to take on the complicated process of securing a therapist. As one youth described, “Depression makes it hard to be motivated about anything, and sometimes you just keep pushing it back as if that will solve the problem.” Similarly, another stated, “Depression is a hell of a disease. I simply didn’t have the energy.” Apathy and numbness related to depression also prevented youth from receiving care with one youth stating, “Too numb from depression to take action.”

Insurance Difficulties

Insurance challenges were very frequently mentioned as a reason youth were unable to receive desired mental health care. This included both lack of insurance coverage as well as insurance coverage that was too limiting to provide appropriate care. One youth without insurance stated, “I could afford one or two visits but did not have health insurance, so multiple visits were not an option, and I needed a lot, so I just didn’t go.” Changes in insurance policies also related to barriers to care for many youth, as exemplified by a youth who stated, “My insurance no longer covers my original therapist, and I’ve been too scared to start over with someone new.” The availability of covered providers was also a major concern with youth commonly making statements such as, “None of the providers in my insurance network have openings.” This was particularly difficult for those looking for LGBTQ competent providers, such as a youth who stated it was very hard finding a provider, “who is LGBT friendly that also accepts my insurance.” Insurance privacy was also a major concern for many youth who received their coverage through a parental plan. For these youth, receiving needed mental health care was not an option as they did not want to have to discuss it with their parents and were deterred by the lack of privacy for their care when under their parental plan. This challenge is exemplified by youth who expressed sentiments such as, “parents don’t believe in mental health professionals, and I’m covered under their insurance, I was afraid they’d find out,” and “my parent that is the insurance holder would be emotionally abusive if I tried going.”

Lack of Provider Availability

Providers who were not taking new clients and who had long appointment waitlists were often mentioned by youth as one of the reasons why they are unable to receive the mental health care they wanted. After finding the motivation to seek mental health care, and negotiating the mental health system to identify a suitable and affordable provider, many youth expressed that they were met with replies of no availability or a long waitlist. For example, one youth stated, “the appointments are backed up twelve months out,” while another indicated, “when I finally found a counselor that could work, wait times were months out, and I still haven’t gotten in to see them.” Other youth received replies that they would be notified when something was available such as a youth who reported, “I’ve been trying to find a therapist. My doctor gave me a list of therapists, but every time I would call and ask to be scheduled for an appointment, then they would say they would call me back when there was an opening but never did.” Many youth reported attempting to contact a large number of therapists, with outreach attempts not resulting in access to care, such as a youth who stated, “I’ve called every provider on a list of referrals (up to 80 places) and none of them had availability. I am entirely forsaken and out of luck.”

Perceived Burdensomeness

Youth often described concerns about not wanting to be a burden to caregivers or on the strained mental health care system. With caregivers, youth were concerned about being a financial burden with the cost of therapy as well as an emotional burden by having others worrying about them. For example, one youth stated, “I did not want to be a physical or financial burden on my single parent (father). We get no support from the ‘mother’ and no government support.” Many youth avoided care so that they didn’t cause stress or worry to their family members, for example, one youth stated, “I feared asking for it because I didn’t want my mom to worry about me or for me to start crying in front of her,” while another stated, “My brother has to go already because he has OCD and extremely bad anxiety, and I don’t want my parents to know another one of their kids is suffering.” Youth also worried about burdening potential therapists, particularly youth who thought their struggles were not bad enough to warrant the time of a therapist. For example, one youth stated, “I’m afraid that I’ll be a burden, and that they only ‘care’ because it’s their job,” while another stated, “The counseling and testing center at my university had wait times on the order of months, and I didn’t want to take away a slot from somebody with worse problems than me.”

Mistrust and Confidentiality Concerns

The LGBTQ youth in our sample reported many concerns about the ability to trust a therapist, particularly related to fears the therapist would disclose sensitive information to family members. For example, one youth stated, “A lot of my family is majorly depressed and suicidal and look to me like a beacon of hope. Because counselors and therapists can report things like suicidal thoughts to parents, and I don’t want to worry my parents, I don’t go.” Other youth worried about therapists disclosing their LGBTQ identity to parents such as one youth who noted, “I was worried that the person would tell my homophobic parents that I am LGBTQ.” Youth also expressed concerns that their therapist might use their words to involuntarily confine them to a mental hospital. These youth made statements such as “I thought if I was honest they’d admit me to a psych ward for being suicidal” and “I knew I wouldn’t have been able to discuss my suicide ideation without being locking up in a psychiatric hospital to be evaluated further.” Others expressed more general concern around involuntary hospitalization such as, “Even though my mental health isn’t too bad and I’m generally really happy, I’m afraid of being put in a mental hospital and losing my freedom.”

Time Constraints

Challenges related to finding time to attend therapy appointments was also mentioned as a major barrier to receiving care. This barrier was common among youth who were enrolled in school and those who were employed. For school, concerns related to both time constraints of the school day such as a youth who stated, “School was preventing me from making an appointment during business hours,” as well as not having enough time in the day due to their workload, such as the youth who stated, “I literally didn’t have the time to go see my therapist because of the work-load my university dumps on me,” were common. Job schedules were also described as not conducive to the time slots available for therapy, with many LGBTQ youth expressing the sentiment that it was, “too hard to get time off from work during therapist hours.” In general, the demand of everyday life made it challenging for many to both initiate and receive care such as a youth who said, “I am too busy working and taking care of things at home to find time to schedule appointments.”

Geographic Challenges

LGBTQ youth also detailed challenges of acquiring desired mental health care in particular regions of the U.S. For example, one youth stated, “I live in a rural, Southern area and do not feel that the level of care or understanding would match my needs unless I drive to a city.” Another youth who was transgender stated, “I live in Texas, so there’s a massive fear that the therapy will all be about how to make me comfortable with NOT transitioning.” While another who lived in Texas stated, “doctors can refuse the LGBTQ community legally in Texas.”

RECOMMENDATIONS

While these data highlight that overall, LGBTQ youth are not able to access the mental health care they desire, they also show multiple steps that could improve mental health outcomes for LGBTQ youth. Although all LGBTQ youth experience unacceptable levels of barriers to desired mental health care, these data also point to sub-groups within the LGBTQ community who experience even greater challenges. Given the disproportionately higher rates of mental health challenges and suicide attempts reported by LGBTQ youth, any barriers to mental health care can have enormous consequences. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been increased national conversations focused on mental health, making now a crucial time to implement needed changes so that all LGBTQ youth can easily access quality mental health care. Below we provide recommendations for addressing barriers to mental health care for LGBTQ youth based on our findings.

Increased Funding for Mental Health Care

Many of the barriers to quality care for LGBTQ youth emanate from an underfunded mental health care system that has ineffective and inequitable policies. For example, 53% of LGBTQ youth stated that they were unable to receive desired mental health care due to an inability to afford care. Inability to afford care was the most frequently endorsed barrier across all intersections of LGBTQ youth. As one youth expressed, “I could afford one or two visits but did not have health insurance, so multiple visits were not an option, and I needed a lot, so I just didn’t go.” Research has consistently found that mental health care significantly reduces suicide attempts (McClellan, Ali, & Mutter, 2020). In order to end suicide among LGBTQ youth there is a dire need to remove all barriers to receiving mental health care, including the cost of care.

- State and federal leaders must allocate appropriate funding to expand public-funded mental health programs, particularly in areas that are underserved such as those that currently have no mental health providers.

- Existing mental health parity laws must be enforced and expanded to ensure that youth are able to access providers who accept their insurance. Proposed policies such as the Behavioral Health Coverage Transparency Act would serve to improve the implementation of mental health parity.

Policy Changes to Support Access to Mental Health Care

Changes that rely only on public health and provider-level transformations are inadequate to fully address the scope of the problem. During COVID-19, policy changes related to reimbursement rates for tele-mental health care and to the provision of out-of-state care have expanded the ability for those in need to receive care. Among LGBTQ youth, age restrictions and parental permissions were among the major barriers to care, including not wanting to get parental permission (36%) and having parents who refused to allow care (16%). Policies around age of consent for mental health treatment, which vary by state, create major barriers for LGBTQ youth. In some cases, these restricting laws can actually endanger LGBTQ youth who are dealing with sensitive issues of coming out, relationship issues, rejection, or even abuse. As one youth noted, “I was worried that the person would tell my homophobic parents that I am LGBTQ.” Finally, a number of LGBTQ youth mentioned concerns around conversion therapy as a reason they did not seek care. Such practices are still legal in the majority of U.S. states and strongly associated with suicide attempts among LGBTQ youth (Green, Price-Feeney, Dorison, 2020).

- All states should develop licensing policies that allow mental health providers to treat youth under age 18, who may otherwise not receive care if parental permission was required. Youth across the country should be able to receive confidential mental health care without needing to ask permission from a parent from whom they fear rejection related to their LGBTQ identity.

- Beyond reducing barriers within each state, there is a need to allow youth to access providers who are most able to provide appropriate care, even across state lines. Although some states provide reciprocity licensing for tele-mental health, there is a need for expansion nationwide.

- In order to truly expand access and reduce disparities, tele-mental health must have reimbursement that occurs at the same level as in-person care. Policy changes put into place to support equal reimbursement for tele-health during COVID-19 must be maintained in the future.

- All mental health care, including tele-mental health, should be based on clinical data. There continues to be a need for additional policies to end the harmful and discredited practice of sexual orientation and gender identity ‘conversion therapy’ that can still occur on youth in the majority of U.S. states.

Improving Cultural Competencies of Mental Health Providers

LGBTQ youth are among those at the highest risk of experiencing mental health challenges; however, these youth noted numerous identity-related barriers of a mental health workforce that is unequipped to provide them the care they need. LGBTQ-specific barriers included concerns around being outed (22%), not having their LGBTQ identity understood (20%) or overly focusing on their LGBTQ identity (16%), and not finding a provider who was LGBTQ (11%). Transgender and nonbinary youth particularly noted this difficulty as expressed by one transgender youth who stated, “The regular ‘LGBT therapists’ only know how to properly help LGB.” Further, Black (62%), Latinx (62%), and Asian American/Pacific Islander (60%) LGBTQ youth reported significantly higher levels of not receiving the mental health care they desired than LGBTQ youth who were White (53%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (53%), or multiple race/ethnicities (55%). Many of these youth noted concerns about the current mental health workforce such as, “Most of the mental healthcare providers in my area are White, and a lot of my anxieties are caused by living in a city plagued by racism and xenophobia. I don’t know that a white mental health professional would understand.” Thus, there is a need to develop a more diverse mental health workforce as well as for the existing workforce to engage in ongoing professional development around anti-racism and addressing LGBTQ-stigma.

- To develop a more diverse workforce, the faculty, staff, and students in mental health training programs need to reflect the diversity of the youth ultimately being served. This can include hiring specifically for individuals with professional expertise, providing funding initiatives to recruit more diverse candidates, and engaging in collaborations with experts in the community, including those with lived experience.

- It is also imperative that all education and training environments are inclusive and supportive of diverse candidates. Training programs tend to have a narrow view of what a successful student’s educational history or trajectory should be. Consequently, there is a great deal of ‘gatekeeping’ that prevents students from non-traditional backgrounds from being admitted to graduate training programs. The consequences of these policies are homogenous cohorts of mental health clinicians who could share very little in common with the youth they are serving.

- Education programs must ensure cultural competence training includes examining and challenging personal biases and understanding the role biases and oppression play in forming and exacerbating the mental health concerns that bring an individual to therapy. Without this increased focus, provider bias and discomfort discussing topics around marginalized identities negatively impact rapport building and clinical outcomes.

Ending Stigma and Reducing Fears in Asking for Help

Mental health stigma prevents many LGBTQ youth from being able to ask for help. Words like “embarrassed,” “ashamed,” and “weakness” were among the most frequently described reasons for not receiving desired mental health care provided by youth in the written responses. Stigma was both internal, such as a youth who described, “The fact that I have these thoughts is shameful to me. I wasn’t ready to get help. I still don’t think I am,” as well as external as evidenced by a youth who stated, “I was taught that needing therapy means you are weak.” Further, the mental healthcare system in the U.S. is fragmented, complex, and can be especially daunting to those already overwhelmed and in need of care. In our study, many youth expressed that they were unable to access mental health due to existing anxiety or depression which made the task of asking for health scary and overwhelming. Based on this data, there is a need for widespread efforts aimed at ending mental health stigma and promoting ways to help youth in asking for help.

- Public health campaigns that rely on messengers trusted by LGBTQ youth, including those with multiple marginalized identities, can be used to promote mental wellness and provide examples of ways youth can ask for help and initiate care.

- There need to be systemic efforts in smaller communities and institutions (like churches and community centers) where mental health conditions are discussed openly. Top-down changes are needed from the public health perspective; however, bottom-up initiatives need to happen concurrently. LGBTQ youth live in all communities across the United States, large and small. These smaller communities are crucial for youth self-acceptance and addressing mental health within them can save many lives.

- Patient navigators can be used to assist LGBTQ youth with the process of understanding insurance benefits and finding LGBTQ-competent providers who meet their needs. Such services need to be widely publicized and demystified.

- Providers should also work to provide options for care that are desirable for youth. This includes the web-based chat and texting options to inquire about appointments and care as well as forms that can be pre-filled out and submitted online. Such steps may provide a less burdensome and anxiety-provoking experience for many youth who desire care.

Integrating Technology to Improve Access to Mental Health Care

Twenty percent of LGBTQ youth were unable to receive the care they desired due to the inability to arrange transportation for appointments and 10% reported they weren’t services located close enough to them. Geographic challenges to obtaining care were also detailed in youth written responses, such as a youth who stated, “I live in a rural, Southern area and do not feel that the level of care or understanding would match my needs unless I drive to a city.” Further, many LGBTQ youth indicated that anxiety related to leaving their home and meeting new people kept them from receiving care. For example, COVID-19 has highlighted that mental health care can be provided via telephone or video conferencing when necessary. Additionally, learning platforms for youth are proliferating during COVID-19, including asynchronous platforms that provide user-paced learning under the guidance of trained facilitators. Such platforms could be used to promote not only traditional education, but also the ways we provide psychoeducation and skills-based learning related to addressing symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- The mental health care system in the U.S. must adapt to the needs of those who are unable to find appropriate mental health care by expanding tele-mental health. Such services ensure that quality care for LGBTQ youth is not limited to only metropolitan areas.

- The advancements in tele-health services prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, including cross-state licensure, should be adopted long term.

- There is a need for both real-time interactions with mental health care providers (i.e., synchronous) and online interactions with providers that can occur at different times at the youth’s convenience (i.e., asynchronous) to address the mental health needs of LGBTQ youth. Having different modalities of delivery allow for great flexibility in youth choice and also provide lower-cost options. Further, asynchronous platforms may allow LGBTQ youth with unaccepting parents more privacy in receiving desired care.

CONCLUSION

Now is the time to act to address barriers to quality mental health care for all LGBTQ youth. Never before has national attention focused so acutely on mental health and well-being in addition to inequities in the provision of health care. Addressing barriers will require an approach that relies on policy and funding changes as well as changes to the ways mental health care providers serve those who are in need of care. The Trevor Project is committed to ensuring that LGBTQ youth are supported throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and going forward by providing 24/7 access to an affirming international community for LGBTQ young people and trained crisis counselors to talk directly with youth in crisis. However, we know that LGBTQ youth also need access to a mental health care system that is equitable, effective, and available for all. We hope others will join us in finding solutions that provide LGBTQ youth with the support they need to thrive.

About The Trevor Project

The Trevor Project is the world’s largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, & questioning (LGBTQ) young people. The Trevor Project offers a suite of 24/7 crisis intervention and suicide prevention programs, including TrevorLifeline, TrevorText, and TrevorChat as well as the world’s largest safe space social networking site for LGBTQ youth, TrevorSpace. Trevor also operates an education program with resources for youth-serving adults and organizations, an advocacy department fighting for pro-LGBTQ legislation and against anti-LGBTQ policies, and a research team to examine the most effective means to help young LGBTQ people in crisis and end suicide. If you or someone you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386, via chat www.TheTrevorProject.org/Help, or by texting START to 678-678.

This report is a collaborative effort from the following individuals at The Trevor Project:

Amy Green, PhD

Director of Research

Samuel Dorison, LLM, MSc

Chief Strategy & Innovation Officer

Myeshia Price-Feeney, PhD

Research Scientist

Recommended Citation: Green, A.E., Price-Feeney, M. & Dorison, S. (2020). Breaking Barriers to Quality Mental Health Care for LGBTQ Youth. New York, New York: The Trevor Project.

Media inquiries:

Kevin Wong

Vice President of Communications

[email protected]

212.695.8650 x407

Research-related inquiries:

Amy Green, PhD

Director of Research

[email protected]

310.271.8845 x242

REFERENCES

Alegria, M., Vallas, M., & Pumariega, A. J. (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 19(4), 759-774.

Auerbach, J., & Miller, B. F. (2020). COVID-19 Exposes the Cracks in Our Already Fragile Mental Health System. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (7), 969-970.

Bowleg, L. (2020). We’re Not All in This Together: On COVID-19, Intersectionality, and Structural Inequality. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (7), 969-970.

Bridge, J. A., Horowitz, L. M., Fontanella, C. A., Sheftall, A. H., Greenhouse, J., Kelleher, K. J., & Campo, J. V. (2018). Age-related racial disparity in suicide rates among US youths from 2001 through 2015. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(7), 697-699.

Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., … & Monstrey, S. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165-232.

Cyrus, K. (2017). Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(3), 194-202.

Green, A.E., Price-Feeney, M. & Dorison, S.H. (2020). Implications of COVID-19 for LGBTQ Youth Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. New York, New York: The Trevor Project. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/blog/implications-of-covid-19-for-lgbtq-youth-mental-health-and-suicide-prevention/

Green, A.E., Price-Feeney, M. & Dorison, S.H. (2019). Research brief: Suicide attempts among LGBTQ Youth of Color. New York, New York: The Trevor Project. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/suicide-attempts-among-lgbtq-youth-of-color/

Green, A. E., Price-Feeney, M., Dorison, S. H., & Pick, C. J. (2020). Self-reported conversion efforts and suicidality among US LGBTQ youths and young adults, 2018. American Journal of Public Health, 110(8), 1221-1227.

Hodgkinson, S., Godoy, L., Beers, L. S., & Lewin, A. (2017). Improving mental health access for low-income children and families in the primary care setting. Pediatrics, 139(1), e20151175.

Hoffmann, J. A., Farrell, C. A., Monuteaux, M. C., Fleegler, E. W., & Lee, L. K. (2020). Association of pediatric suicide with county-level poverty in the United States, 2007-2016. JAMA pediatrics, 174(3), 287-294.

Johns M.M., Lowry R., Andrzejewski J., et al. (2019). Transgender Identity and Experiences of Violence Victimization, Substance Use, Suicide Risk, and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — 19 States and Large Urban School Districts, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report;68,67–71.

Kann L, McManus T., Harris W.A., et al. (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report(SS-8),1–114.

Lindsey, M. A., Sheftall, A. H., Xiao, Y., & Joe, S. (2019). Trends of Suicidal Behaviors Among High School Students in the United States: 1991–2017. Pediatrics, e20191187.

McClellan, C., Ali, M. M., & Mutter, R. (2020). Impact of Mental Health Treatment on Suicide Attempts. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. doi: 10.1007/s11414-020-09714-4

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697.

Price-Feeney, M., Green, A. E., & Dorison, S. (2020). Understanding the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), 684-690.

Salway, T., Ross, L. E., Fehr, C. P., Burley, J., Asadi, S., Hawkins, B., & Tarasoff, L. A. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of disparities in the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt among bisexual populations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 89-111.

Steele, L. S., Daley, A., Curling, D., Gibson, M. F., Green, D. C., Williams, C. C., & Ross, L. E. (2017). LGBT identity, untreated depression, and unmet need for mental health services by sexual minority women and trans-identified people. Journal of Women’s Health, 26(2), 116-127.

Sullivan, E. M., Annest, J. L., Simon, T. R., Luo, F., & Dahlberg, L. L. (2015). Suicide trends among persons aged 10–24 years—United States, 1994–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(8), 201-205.

Williams, K. A., & Chapman, M. V. (2012). Unmet Health and Mental Health Need Among Adolescents: The Roles of Sexual Minority Status and Child–Parent Connectedness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 473-481.