Background

LGBTQ young people spend an average of five hours per day online, approximately 45 minutes more than their non-LGBTQ peers (GLSEN, 2013). The evidence on the impact of online spaces on young people’s well-being is nuanced. While online spaces can pose harm to LGBTQ young people, such as higher risk of cyberbullying compared to their non-LGBTQ peers (Abreu & Kenny, 2018), online spaces have also been found to support the mental health and well-being of LGBTQ young people through the exploration of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities, peer connection, and social support (Berger et al., 2022). In particular, LGBTQ young people of color who hope to find support in online spaces are often exposed to racism, which is broadly present online (Noble, 2018) and is related to poorer mental health among young people of color (Tynes et al., 2019). Despite these challenges, past research has also shown that some online spaces may still provide safe spaces for LGBTQ young people who hold multiple marginalized identities (Lucero, 2017). However, no research has examined which specific online spaces are currently seen as safe and supportive by LGBTQ young people of color at the intersection of their multiple marginalized identities. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People, this brief aims to identify specific online spaces where LGBTQ young people of color feel safe and understood.

Results

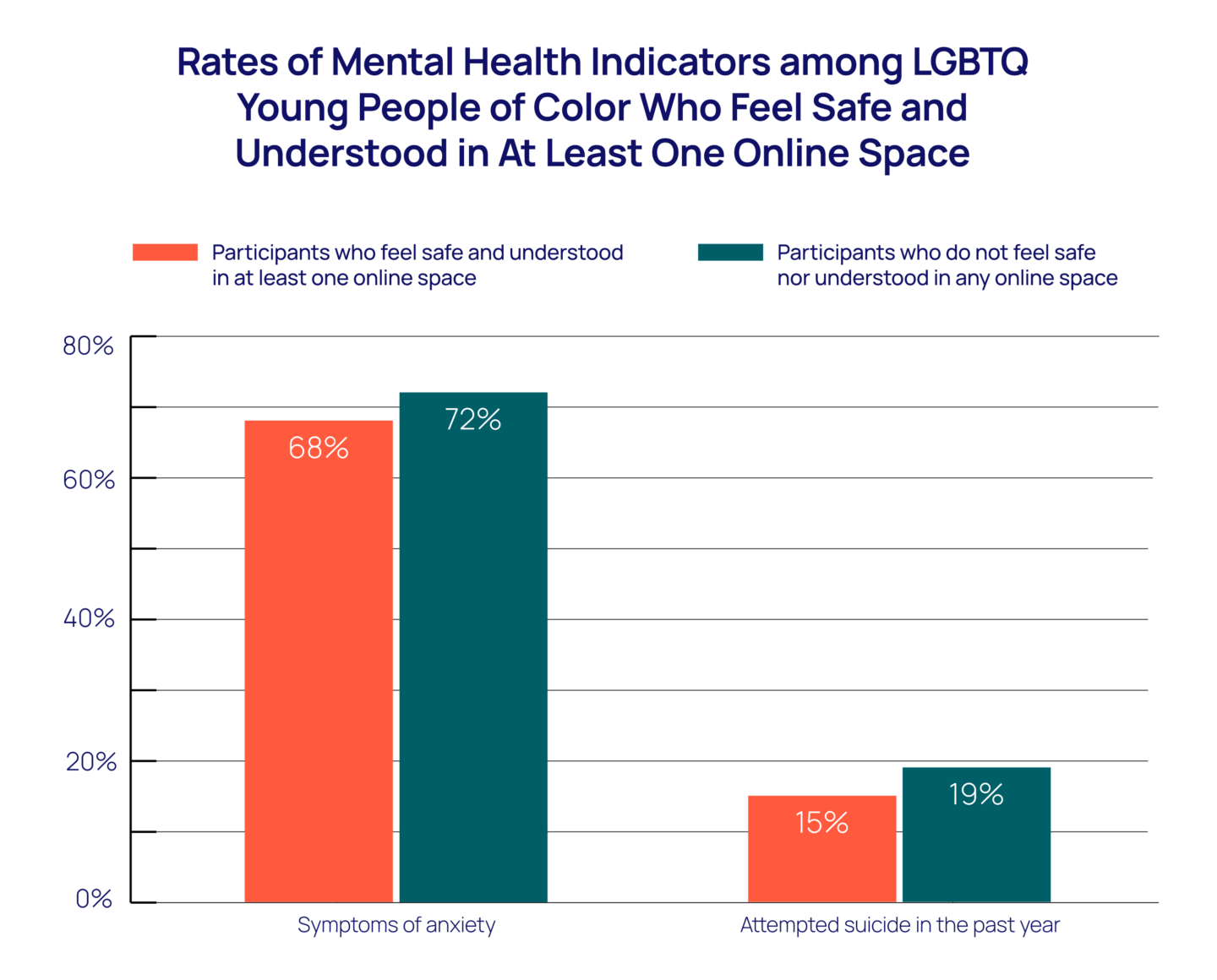

Feeling safe and understood in at least one online space is associated with lower suicide risk in the past year and lower rates of recent anxiety for all LGBTQ young people, and for LGBTQ young people of color in particular. Overall, LGBTQ young people who reported feeling safe and understood in at least one online space had 20% lower odds of attemping suicide in the past year (aOR=0.80, 95% CI [0.72–0.88], p<0.001), and 15% lower odds of recent anxiety (aOR=0.85, 95% CI [0.79–0.92], p<0.001), compared to LGBTQ young people who reported not feeling safe and understood in any online space. LGBTQ young people of color and our overall sample of LGBTQ young people had similar lower odds of past year suicide attempt when they reported feeling safe and understood in at least one online space. On the other hand, the association to lower rates of recent anxiety is even stronger among LGBTQ young people of color. LGBTQ young people of color who reported feeling safe and understood in at least one online space had 19% lower odds of recent anxiety (aOR=0.81, 95% CI [0.73–0.91], p<0.001), compared to LGBTQ young people of color who reported not feeling safe and understood in any online space.

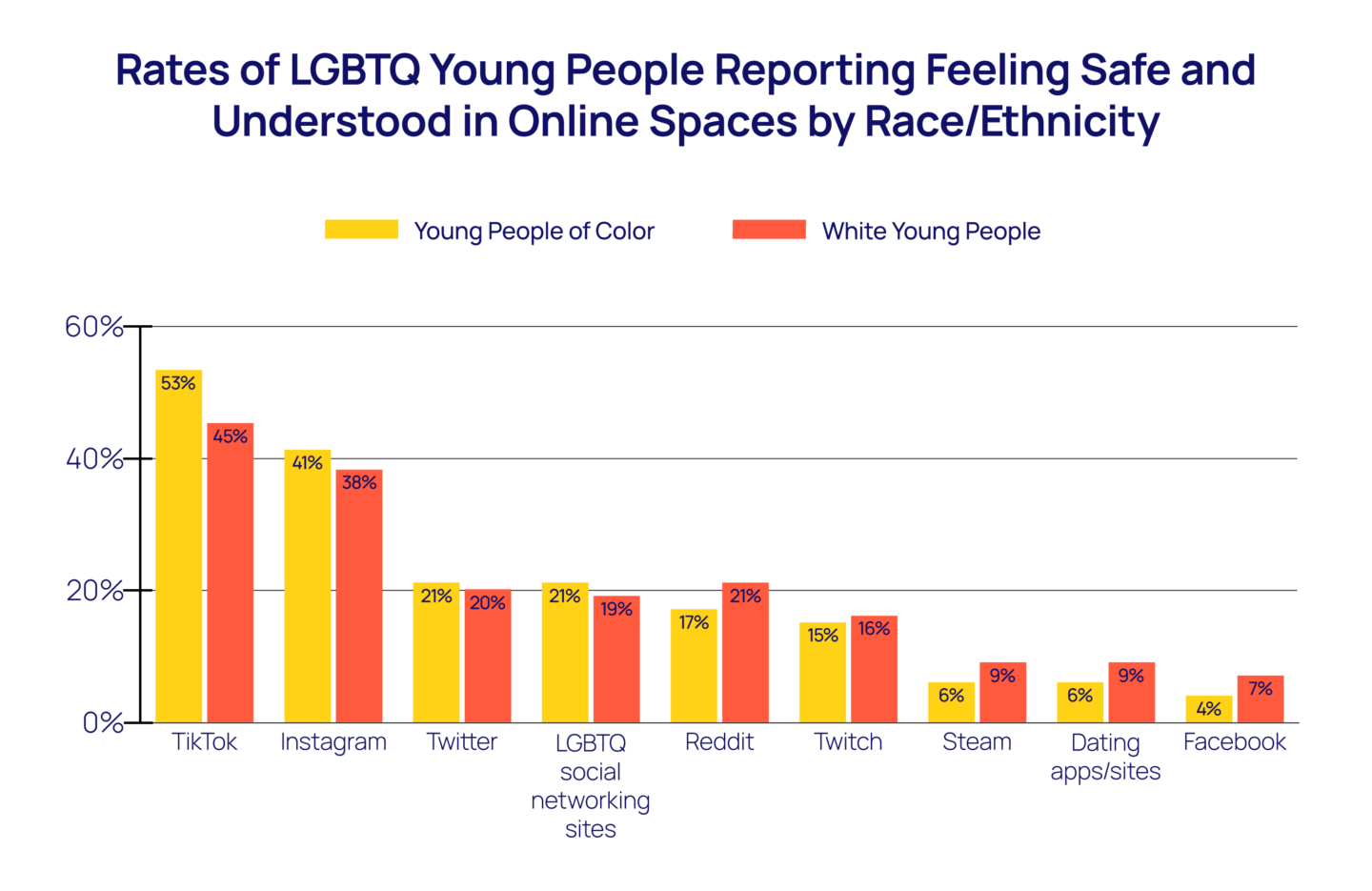

LGBTQ young people of color reported different rates of feeling safe and understood in specific online spaces compared to their White peers. Overall, the rates of reporting feeling safe and understood in at least one online space were similar between LGBTQ young people of color (80%) and White LGBTQ young people (81%), and the average number of online spaces where both groups reported feeling safe and understood were also similar (M = 2.68, SD = 2.16 and M = 2.69, SD = 2.14, respectively). However, there were significant differences in where LGBTQ young people of color and White LGBTQ young people felt safe and understood online. Compared to their White peers, LGBTQ young people of color reported significantly higher rates of feeling safe and understood on TikTok (53% vs. 45%), Instagram (41% vs. 38%), Twitter (21% vs. 20%), and LGBTQ social networking sites (21% vs. 19%), and reported significantly lower rates of feeling safe and understood on Reddit (17% vs. 21%), Twitch (15% vs. 16%), Steam (6% vs. 9%), dating apps (6% vs. 9%), and Facebook (4% vs. 7%).

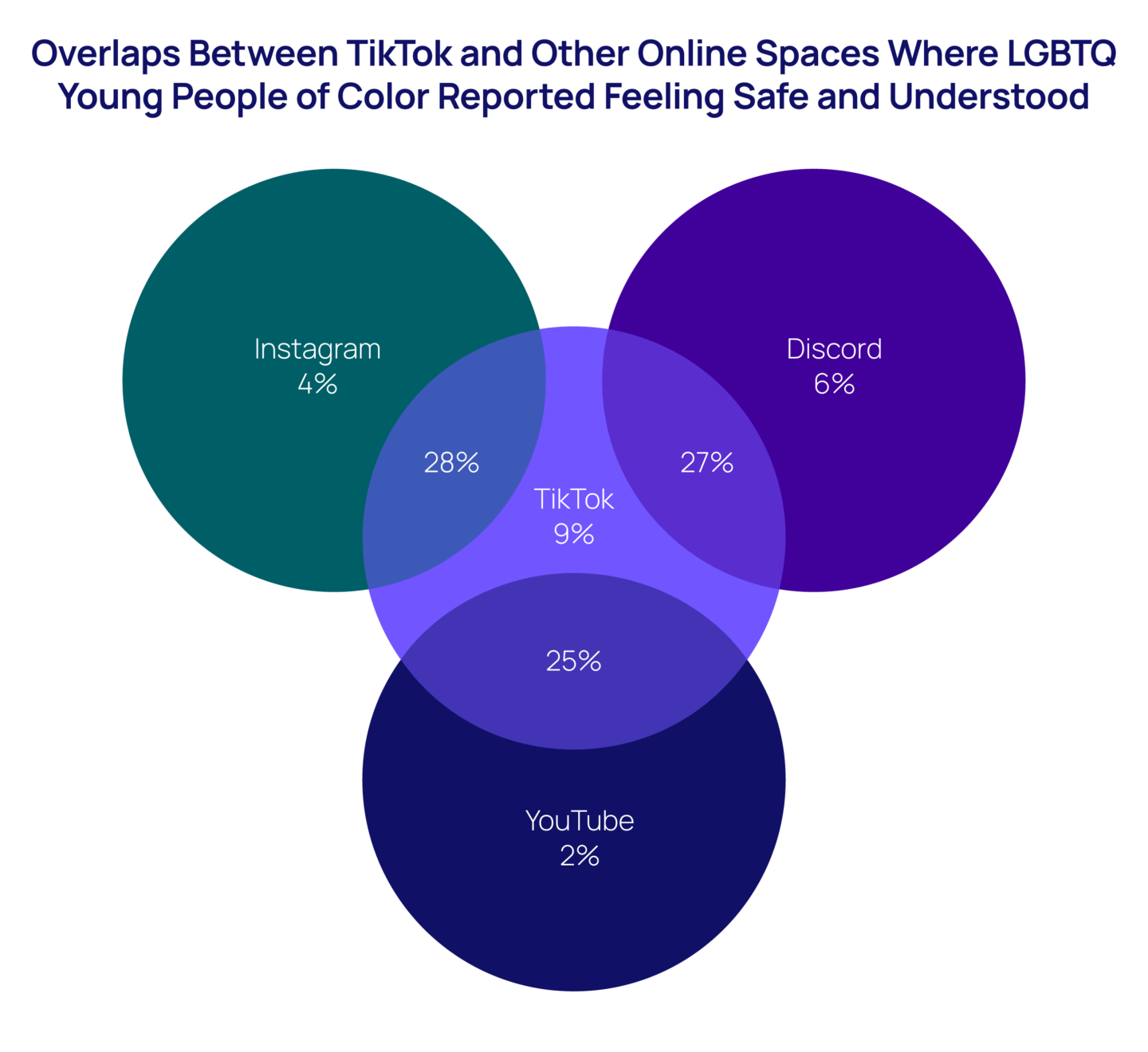

TikTok is the leading online space where the most LGBTQ young people of color reported feeling safe and understood, followed by Discord, Instagram, and YouTube. In our sample, over half (53%) of LGBTQ young people of color reported feeling safe and understood on TikTok, 42% on Discord, 41% on Instagram, and 33% on YouTube. Furthermore, LGBTQ young people of color who reported feeling safe and understood on TikTok were likely to also feel safe and understood on Discord, Instagram, or YouTube. Overall, 28% of LGBTQ young people of color reported feeling safe and understood on both TikTok and Instagram, 27% on both TikTok and Discord, and 25% on both TikTok and YouTube. Conversely, fewer LGBTQ young people of color exclusively reported feeling safe on only one of these online spaces (i.e., TikTok, Instagram, Discord, and YouTube) and not in the other three online spaces. Specifically, 9% of LGBTQ young people of color reported feeling safe only on TikTok and not Discord, Instagram, or YouTube; 6% only on Discord; 4% only on Instagram; and 2% only on YouTube.

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2022 of 28,524 LGBTQ young people recruited via targeted ads on social media. The item assessing where LGBTQ young people feel safe and understood online asked respondents, “Where on the internet do you feel safe and understood as an LGBTQ young person? Please select all that apply.” Response options included 1) Instagram, 2) Facebook, 3) TikTok, 4) YouTube, 5) Twitter, 6) Reddit, 7) Quora, 8) Discord, 9) Steam, 10) Twitch, 11) Social networking sites just for LGBTQ young people, 12) Dating apps/sites, 13) Another place online (please specify), and 14) I don’t feel safe and understood as an LGBTQ young person anywhere on the internet. Questions assessing suicide risk were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Current symptoms of anxiety were measured using the GAD-2 (Plummer et al., 2016). The item gathering the race/ethnicity of LGBTQ young people asked respondents, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” Response options included 1) Asian/Asian American, 2) Black/African American, 3) Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, 4) Indigenous/Native, 5) Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, 6) Middle Eastern or Northern African, 7) White, 8) More than one race or ethnicity, and 9) Another race or ethnicity (please specify). To evaluate racial/ethnic differences in this study, Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI), Black, Latinx, Middle Eastern/Northern African (MENA), Native/Indigenous, and young people who identified with more than one race/ethnicity were grouped as young people of color. Association rule analyses with the Apriori algorithm were conducted to determine which online spaces were often selected in combination by LGBTQ young people as spaces they felt safe and understood. Crosstabs and chi-square analyses were used to examine frequencies and differences in rates among different groups. Adjusted logistic regression models were conducted to determine the association between LGBTQ feeling safe and understood in at least one online space and attempting suicide in the past year, while controlling for age, Census Region, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual identity. All reported comparisons are statistically significant at least at p<0.05. This means there is less than a 5% probability these results occurred by chance.

Looking Ahead

Although sometimes portrayed as negative or harmful in the media (O’Reilly et al., 2018), our findings illustrate the possible benefits of safe and supportive online spaces for LGBTQ young people, especially LGBTQ young people of color. Additionally, these findings show that LGBTQ young people of color and White LGBTQ young people reported feeling safe and understood in different online spaces.

This brief echoes past research that urges researchers to tailor the study of young people’s online behaviors to the unique characteristics and needs of each community (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). Adults who hope to make recommendations about online spaces to LGBTQ young people of color must consider both their LGBTQ and racial/ethnic identities to provide recommendations that are the most likely to be safe for them, as some spaces may currently be less safe for young people who hold multiple marginalized identities. We found that TikTok, Discord, Instagram, and YouTube are currently some of the online spaces where the most LGBTQ young people of color report feeling safe and understood. Furthermore, a survey in 2022 revealed that TikTok is one of the most popular online spaces among young people in the United States (Vogels et al., 2022). Based on our findings, Discord, Instagram, and YouTube may be useful recommendations to young people who already use and feel safe on TikTok.

Overall, these findings underscore the benefits that online spaces may have for LGBTQ young people of color, and identify some of the key online spaces where they feel safe and understood. It is important to note that the landscape of online spaces is ever-changing. Appropriate digital literacy training that teaches LGBTQ young people of color how to responsibly learn, create, and participate in online spaces may be key to ensuring their long-term well-being online (Common Sense Media, 2019). Recent research has shown that digital literacy training may increase the frequency of positive online interactions (American Psychological Association, 2023). Future research and development on digital literacy training must include components on recognizing and coping with both racist and anti-LGBTQ online content. It is also an important responsibility of those who build technology to continue adapting and innovating to keep online spaces safe for LGBTQ young people of color (American Psychological Association, 2023; Noble, 2018).

The Trevor Project remains committed to improving the mental health of LGBTQ young people of color. We recognize that all LGBTQ young people deserve to feel safe and understood in online spaces, and tailored recommendations are necessary to address the unique challenges LGBTQ young people of color face in online spaces. Our TrevorSpace platform is an affirming online community for LGBTQ young people between the ages of 13 to 24 years old. Young people can explore their identities, find peer support, and make friends in a moderated community designed for them. Our free crisis services are committed to ensuring that all LGBTQ young people, including LGBTQ young people of color, are provided high-quality, culturally-sensitive care 24/7 via phone, chat, and text. We have worked to create a team of diverse highly trained counselors that aligns with the demographics of the young people we serve. Finally, our Research team is committed to the ongoing dissemination of findings specific to LGBTQ young people of color to help The Trevor Project and others better address the unique needs of LGBTQ young people of color.

References

- Abreu, R. L., & Kenny, M. C. (2018). Cyberbullying and LGBTQ youth: A systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(1), 81-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0175-7

- American Psychological Association. (2023). Health advisory on social media use in adolescence. https://www.apa.org/topics/social-media-internet/health-advisory-adolescent-social-media-use.pdf

- Berger, M. N., Taba, M., Marino, J. L., Lim, M. S. C., & Skinner, S. R. (2022). Social media use and health and well-being of lesbian,gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(9), e38449. https://doi.org/10.2196/38449

- Common Sense Media. (2019, May 10). Digital citizenship | Common sense education. https://www.commonsense.org/education/digital-citizenship

- GLSEN, CiPHR, & CCRC. (2013). Out online: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth on the Internet. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/Out_Online_Full_Report_2013.pdf

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020).Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

- Lucero, L. (2017). Safe spaces in online places: Social media and LGBTQ youth. Multicultural Education Review, 9(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2017.1313482

- Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479833641.001.0001

- O’Reilly, M., Dogra, N., Whiteman, N., Hughes, J., Eruyar, S., & Reilly, P. (2018). Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing?Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(4), 601–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518775154

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematicreview and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

- Tynes, B. M., Willis, H. A., Stewart, A. M., & Hamilton, M. W. (2019). Race-related traumatic events online and mental health amongadolescents of color. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(3), 371–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.006

- Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63(2),221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024

- Vogels, E. A., Gelles-Watnick, R., & Massarat, N. (2022). Teens, social media and technology 2022. Pew Research Center.https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/

For more information please contact: [email protected]