Background

Among the broader population of youth ages 10–24 in the U.S., suicide rates are higher in rural than in urban communities (Fontanella et al., 2015). Further, data from GLSEN’s National School Climate Survey indicate that LGBTQ youth from small towns or rural areas are more likely to hear anti-LGBTQ remarks and experience discrimination in schools than those from urban and suburban schools (Kosciw et al., 2020). However, little research has specifically examined differences in mental health and suicide risk based on whether LGBTQ youth live in urban or rural areas. One study of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning (LGBQ) youth found that, although both rural and non-rural LGBQ youth reported significantly greater risk of depression compared to their non-LGBQ peers, there were no significant differences in depression when comparing rural LGBQ youth to LGBQ youth from urban and suburban areas (Price-Feeney, Ybarra, & Mitchell, 2019). Further, a study of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth in Canada also found similar rates of depression among rural and urban youth; however, they found that rural LGB boys, but not rural LGB girls, were more likely to consider and attempt suicide than those from urban and suburban areas (Poon & Saewyc, 2009). Given the mixed findings on LGBTQ youth in rural areas and small towns, there is a need for additional research, particularly among transgender and nonbinary youth. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief examines depression and suicide risk among LGBTQ youth from rural areas and small towns compared to urban and suburban areas.

Results

Nearly half (49%) of LGBTQ youth in rural areas and small towns stated that their community was somewhat or very unaccepting of LGBTQ people compared to just over a quarter (26%) of those in urban and suburban areas. In total, only 4% of rural LGBTQ youth reported that their community was very accepting of LGBTQ people. Approximately half of the sample lived in urban (15%) or suburban (34%) areas, with the other half living in a small city/town (41%) or rural area (10%). LGBTQ youth in rural areas and small towns also reported higher rates of experiencing LGBTQ-based discrimination (61% vs. 56%) and physical harm (21% vs. 17%) in the past year compared to those in urban and suburban areas.

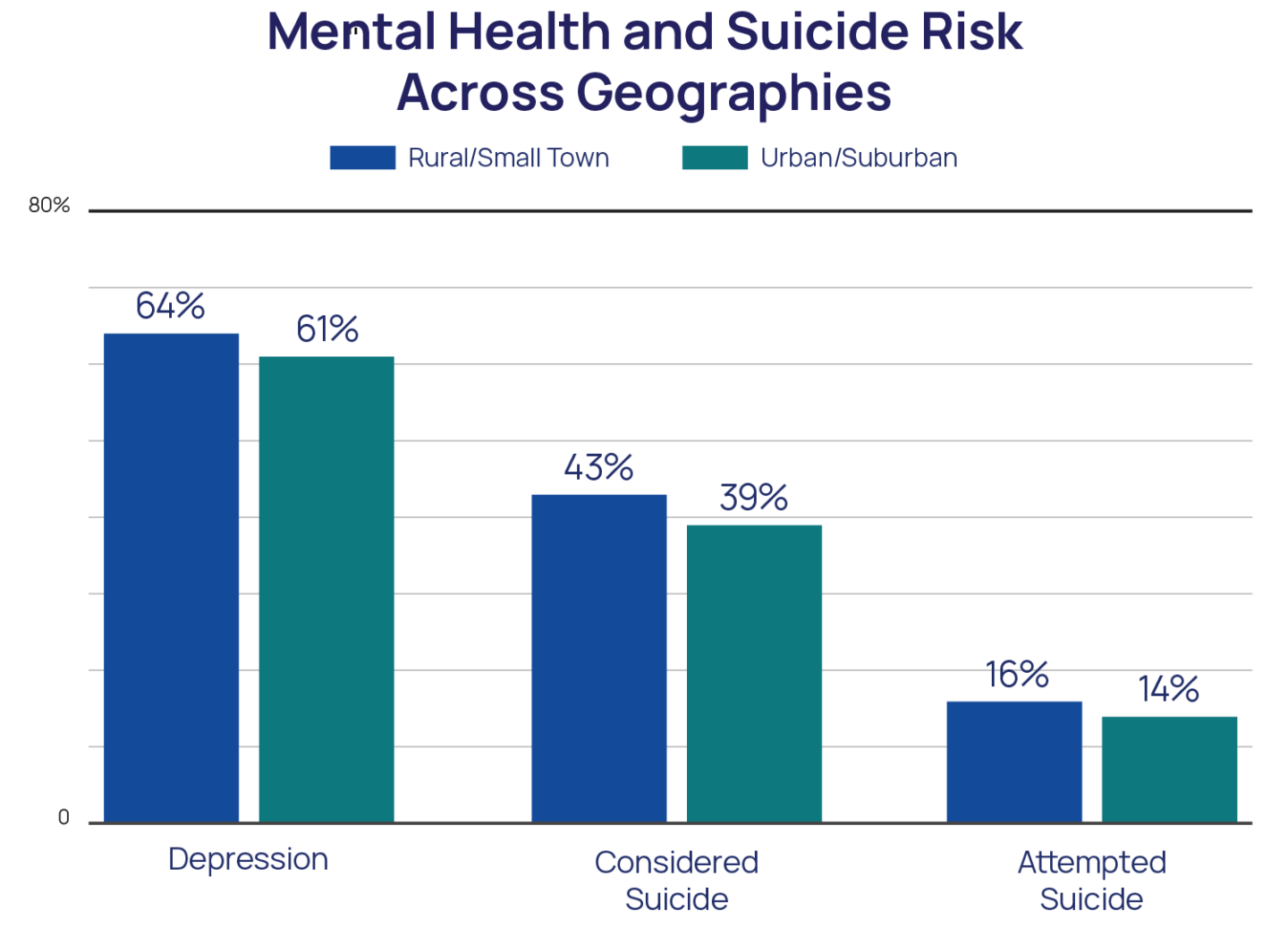

LGBTQ youth in rural areas and small towns had slightly greater odds of experiencing symptoms of depression (aOR = 1.09, p<.001), considering suicide (aOR = 1.14, p<.001), and attempting suicide (aOR = 1.19, p<.001) compared to those in urban and suburban areas. Generally, rates were only slightly higher among those in small towns and rural areas than those in urban and suburban areas. While transgender and nonbinary youth generally had worse mental health and suicide risk compared to cisgender LGBQ youth, those from small towns and rural areas reported only slightly higher rates of depression (71% vs 69%), considering suicide (53% and 48%), and attempting suicide (21% vs 19%) compared to those from urban and suburban areas. Differences between small towns/rural areas and urban/suburban areas were also relatively comparable within gender identity (e.g., cisgender boy/man, cisgender girl/woman, transgender boy/man, transgender girl/woman, and nonbinary youth).

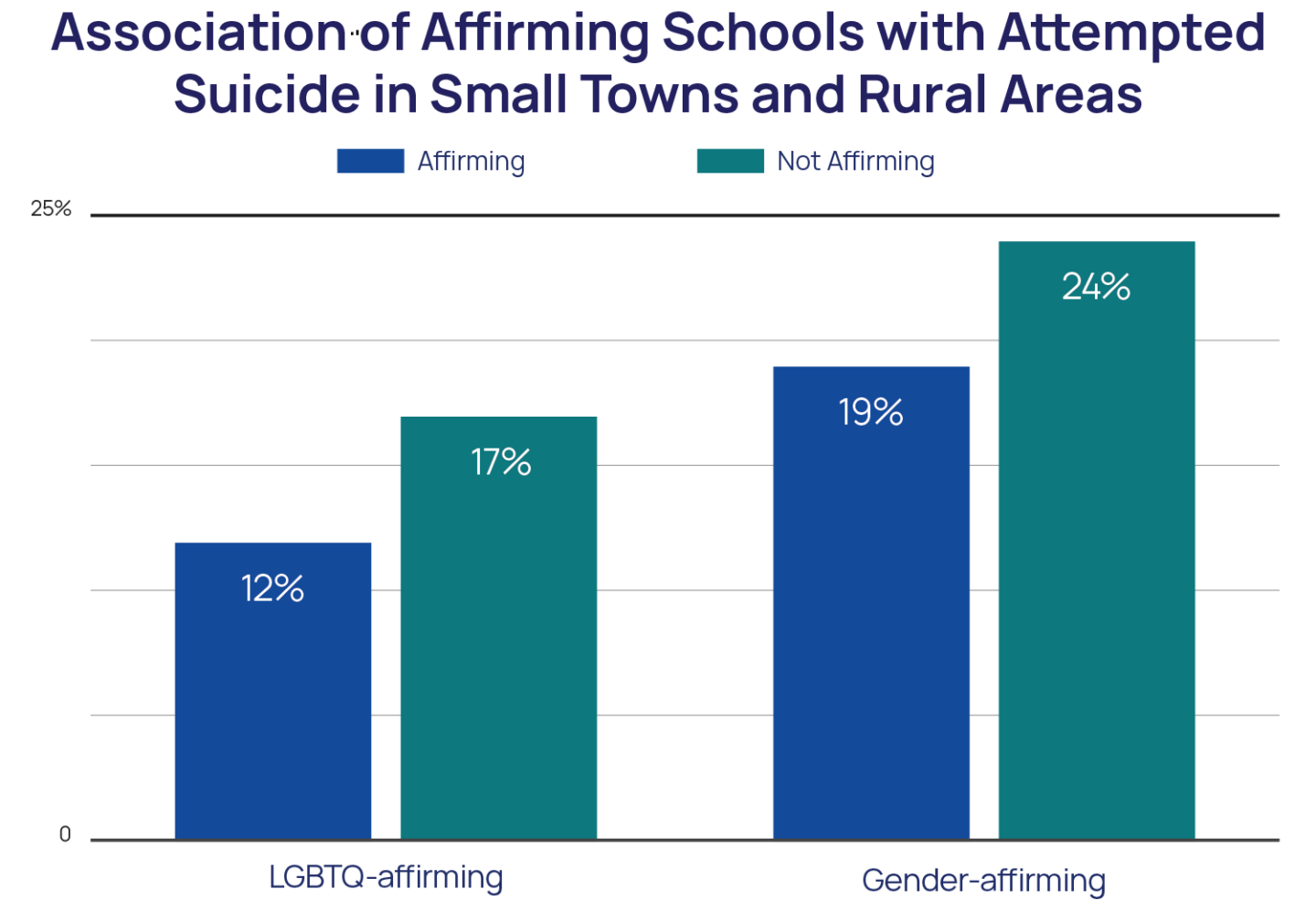

Access to LGBTQ-affirming schools in small towns and rural areas is associated with lower suicide risk. Although LGBTQ youth from small towns and rural areas had less access to LGBTQ-affirming schools (48% vs. 56%) than those in urban and suburban areas, those with affirming schools had 35% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 0.65). Further, among transgender and nonbinary youth, access to schools that were gender-affirming was associated with an over 25% lower risk of a past-year suicide attempt (aOR = 0.74, p<.001). However, transgender and nonbinary youth in small towns and rural areas had less access to gender-affirming schools (40% vs. 46%) than those in urban and suburban areas.

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between October and December of 2020 of 34,759 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. To determine the type of area where youth resided, they were asked, “Which of the following best describes the area you live in?” with response options of 1) In a large city, 2) Just outside of a large city (such as in a suburb), 3) In a small city or town, or 4) In a rural area (such as out in the country). For the current report, those who selected large city or just outside the city were considered urban or suburban, while those who selected small city, town, or rural area were considered rural or small town. Items on considering and attempting suicide in the past 12 months were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Depression was measured using the PHQ-2 (Richardson et al., 2010). All LGBTQ youth in the sample were asked to endorse whether or not their school (if enrolled) was LGBTQ-affirming. Transgender and nonbinary youth were also asked whether their school (if enrolled) was gender-affirming. Adjusted logistic regression models controlled for race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and sexual identity.

Looking Ahead

Supporting previous research, these findings show that despite higher levels of rejection, discrimination, and victimization experienced by LGBTQ youth in small towns and rural areas, the resulting disparities in depression and suicide risk are relatively small. For example, in our data, LGBTQ youth in small towns and rural areas reported more than double the rate of living in a community that was unaccepting of LGBTQ people compared to those in urban and suburban areas, yet the odds of experiencing depression, considering suicide, or attempting suicide were only 10–20% greater. Together, these findings indicate that there are likely protective factors that operate to minimize disparities in mental health and suicide risk in small towns and rural regions. Future research should explore positive experiences and/or strengths reported by LGBTQ youth in small towns and rural regions to determine which factors facilitate well-being even in environments that are less accepting of LGBTQ people.

Although LGBTQ youth in small towns and rural regions had lower rates of reporting their schools to be LGBTQ- or gender-affirming spaces, those who had access to affirming schools reported significantly lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year. Such findings, along with higher rates of LGBTQ-based discrimination and victimization in small towns and rural areas, point to the need for greater investment in school policies and practices that support LGBTQ youth in small towns and rural areas. Although implementing school policies and practices to support LGBTQ youth in small towns and rural areas is often fraught with barriers such as fewer LGBTQ-specific community resources and greater anti-LGBTQ sentiment in the community (Green et al., 2018), making these changes at the school level can allow youth to be supported in their identity, and perhaps thrive in ways beyond their LGBTQ peers in urban and suburban areas, given other potential protective factors found in small towns and rural areas.

The Trevor Project is committed to finding ways for all LGBTQ youth to feel safe and supported. LGBTQ youth in small towns and rural areas may have less access to in-person affirmation and support, creating a greater need for our 24/7 crisis services to connect with an accepting and affirming adult as well as our TrevorSpace platform to connect with supportive peers. Trevor’s research, advocacy, and education teams are focused on ensuring that LGBTQ youth, and stakeholders working directly with them across all regions and locations, are included in efforts to prevent suicide and achieve access to life-saving resources.

References

- Fontanella, C. A., Hiance-Steelesmith, D. L., Phillips, G. S., Bridge, J. A., Lester, N., Sweeney, H. A., & Campo, J. V. (2015). Widening rural-urban disparities in youth suicides, United States, 1996-2010. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(5), 466-473.

- Green, A. E., Willging, C. E., Ramos, M. M., Shattuck, D., & Gunderson, L. (2018). Factors impacting implementation of evidence-based strategies to create safe and supportive schools for sexual and gender minority students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(5), 643-648.

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students—Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 79(Suppl-1), 19–27.

- Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., Truong, N. L., & Zongrone, A. D. (2020). The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN.

- Poon, C. S., & Saewyc, E. M. (2009). Out yonder: Sexual-minority adolescents in rural communities in British Columbia. American Journal of Public Health, 99(1), 118-124.

- Price-Feeney, M., Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2019). Health indicators of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other sexual minority (LGB+) youth living in rural communities. The Journal of Pediatrics, 205, 236-243.

- Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1097–e1103.

For more information please contact: [email protected]