Summary

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth facing significant disparities in suicide risk compared to their straight and cisgender peers, based largely on the ways they are treated in their broader environment (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020; Meyer, 2016). Compulsory education results in most LGBTQ youth spending the majority of their waking hours in school, a setting that can serve both risk and protective functions. As a new academic year begins, LGBTQ students are preparing to enter into spaces that may or may not be affirming to their LGBTQ identities. Among LGBTQ middle and high school students, 59% felt unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation, 37% because of their gender, and 42% because of their gender expression (GLSEN, 2020). Our previous findings show that LGBTQ youth in affirming schools had nearly 40% lower odds of attempting suicide compared to LGBTQ youth in non-affirming schools (The Trevor Project, 2020). One way schools can support LGBTQ youth is by including positive content about LGBTQ people and issues in classroom curriculums. Representation in school curriculums can affirm LGBTQ youth’s sexual and gender identities. In addition to creating affirming environments, schools can also prevent suicide by providing all staff and students with comprehensive suicide prevention training. Findings show that the majority of youth, including LGBTQ youth, share their thoughts of suicide with a peer (Michelmore & Hindley, 2012; The Trevor Project, 2019). Inclusion of suicide prevention may not only train young people to support their peers who are in crisis but may also be beneficial to their own well-being. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief explores the inclusion of LGBTQ people or issues and suicide prevention in middle and high school curriculums.

Results

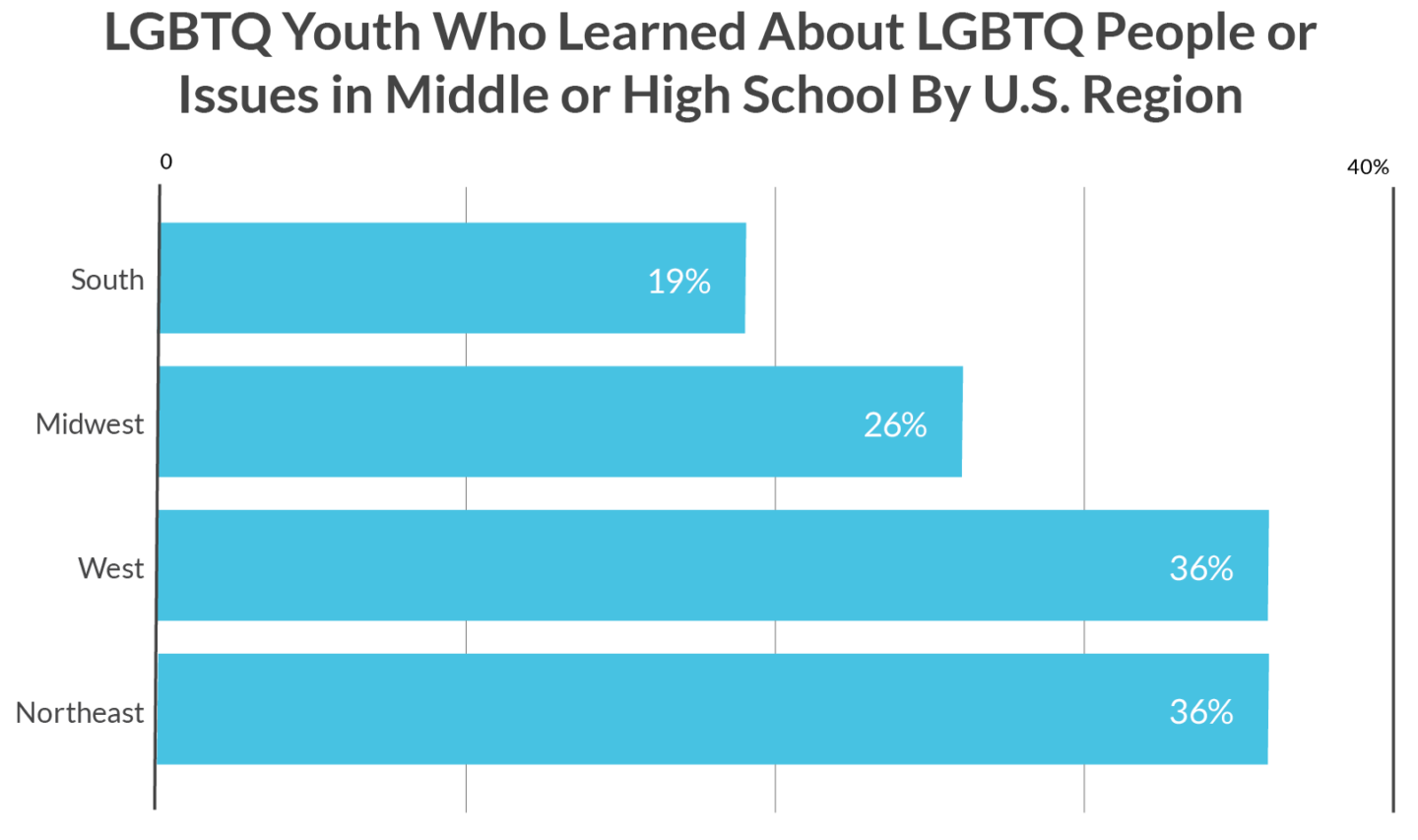

Only 28% of middle and high school LGBTQ students reported that they had ever learned about LGBTQ people or issues in their classes at school. Among students who had ever learned about LGBTQ people or issues, most heard about them in health class (35%) or history class (35%). Youth also stated they learned about them as part of a sexual education class (30%), and 13% couldn’t remember in which class they learned about them. Students living in the Western (36%) and Northeastern (36%) parts of the U.S. reported higher rates of learning about LGBTQ people or issues in class when compared to both the Midwestern (26%) and Southern (19%) regions.

Nearly 2 out of 3 (66%) middle and high school LGBTQ students reported having learned about suicide prevention in school. These rates were higher among students who lived in the Midwestern (70%) and Western (69%) regions, compared to the Northeastern and Southern regions (both 63%). Furthermore, 57% of LGBTQ middle school students reported having a suicide prevention curriculum compared to 68% of LGBTQ high school students.

Students who learned about suicide prevention in school had 28% higher odds of feeling somewhat or very prepared to help a friend who was struggling with thoughts of suicide (aOR=1.28). Overall, 75% of students who learned about suicide prevention in school reported feeling somewhat or very prepared to help a friend who was struggling with thoughts of suicide compared to 70% of students who had not learned about suicide prevention in school.

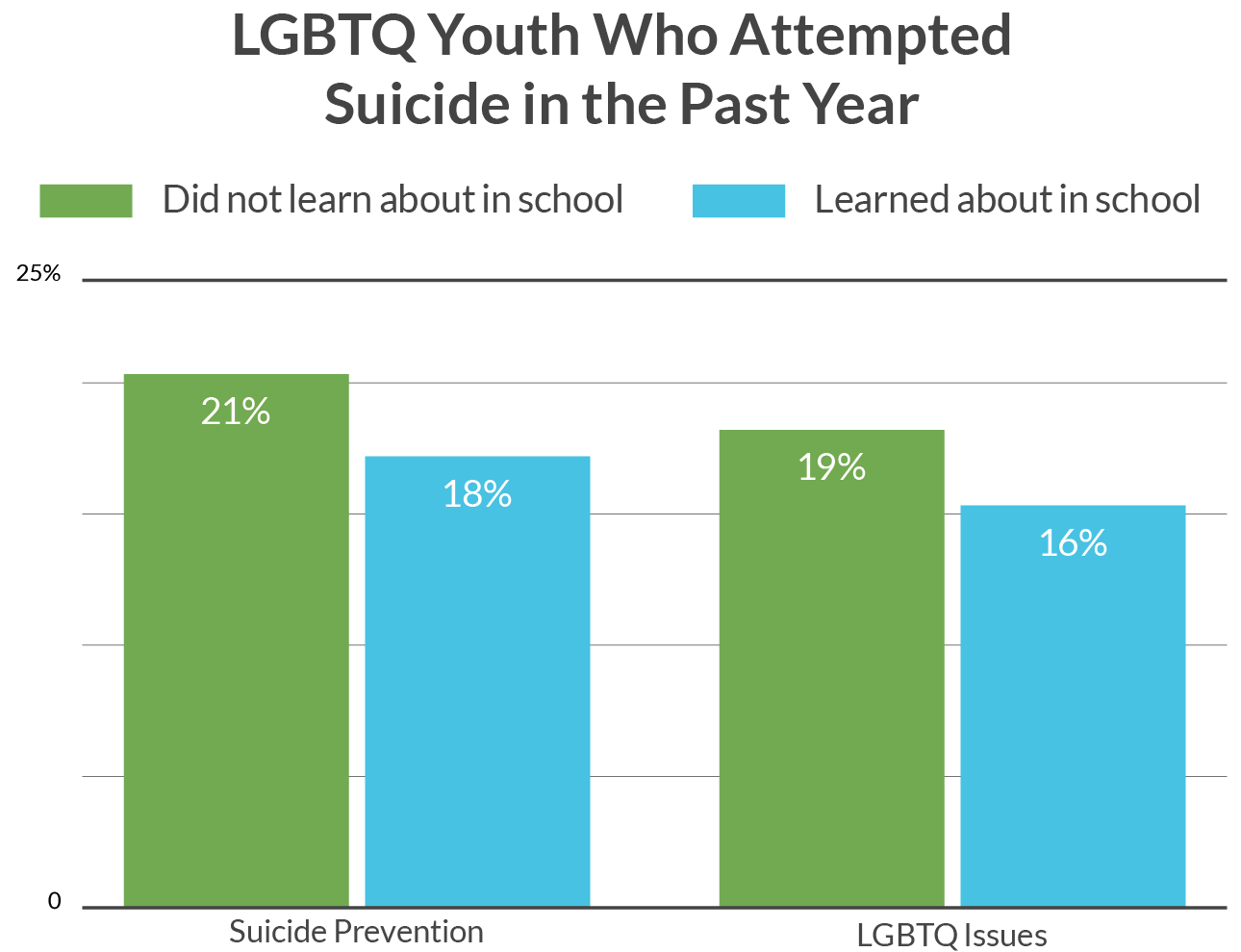

Learning about LGBTQ people/issues or about suicide prevention in schools was associated with significantly lower odds of a past-year suicide attempt among LGBTQ students. LGBTQ youth who learned about LGBTQ issues or people in classes at school had 23% lower odds of reporting a suicide attempt in the past 12 months (aOR=.77). Among middle and high school LGBTQ students, 19% who reported never learning about LGBTQ people or issues in school attempted suicide in the past 12 months compared to 16% of students who had learned about LGBTQ people or issues in class. Furthermore, students who learned about suicide prevention in school had a 23% lower odds of reporting a suicide attempt in the past 12 months (aOR=.77).

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between October and December 2020 of 34,759 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. These analyses included 19,175 youth who were currently enrolled in middle or high school at the time of survey completion. Classroom experiences with LGBTQ material were assessed by asking “Have you ever learned about LGBTQ people or issues in your classes at school?” with response options: No; Yes, in health class; Yes, as part of sexual education class; Yes, in history class; Yes, in another class; Yes, but I don’t remember which class; and I don’t remember if I learned about LGBTQ people or issues in school. Youth could select all that apply. Participants were also asked “Have you learned about suicide prevention in school?” and, separately, “How prepared do you feel to help a friend who is struggling with thoughts of suicide?”. The latter had response items “Not at all,” “A little bit,” “Somewhat,” and “Very much.” Our item on attempted suicide (“During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”) was taken from the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Adjusted odds ratios controlled for age, race/ethnicity, income, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and sexual identity.

Looking Ahead

These findings show support for schools’ potential to serve as protective factors for LGBTQ youth. Learning about LGBTQ people and issues in school curriculum is associated with decreases in suicide attempts among LGBTQ youth. This highlights the need to implement instruction that is affirming to youth’s identities. Being that schools are a place where the majority of school-aged youth are forced to spend most of their waking hours, they should be a place that supports their well-being. However, what remains unknown is how the presentation of such material made youth feel, which should be explored in future research. Unfortunately, there are still laws in existence at the state and local levels that explicitly forbid educators from discussing LGTBQ people or topics in a positive light, if at all, nearly all of which are in the South (GLSEN, 2018). There has also been a resurgence of these laws in recent legislative sessions alongside efforts to ban discussions related to critical race theory.

This research also underscores the value of suicide prevention in schools. Learning about suicide prevention in schools not only seems to help LGBTQ students feel better prepared to help a friend who might be struggling with thoughts of suicide, it also seems to help prevent their own suicide attempts. Ideally, suicide prevention discussions in schools should precede times when youth might have to use it, but with LGBTQ students in middle school reporting lower rates of suicide prevention training compared to LGBTQ students in high school, this does not seem to be the case.

At The Trevor Project, our advocacy team works year-round to encourage the adoption of the Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention, created in consultation with suicide prevention experts at The Trevor Project, The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, The American School Counselor Association, and The National Association of School Psychologists, to help educators and school administrators implement comprehensive suicide prevention policies in communities nationwide. We also provide education trainings on suicide prevention and LGBTQ ally training. Finally, our crisis services team works 24/7 to be available for LGBTQ youth who are having thoughts of suicide and may not feel comfortable disclosing to others.

| ReferencesGLSEN. (2018). Laws Prohibiting “Promotion of Homosexuality” in Schools: Impacts and Implications (Research Brief). New York: GLSEN.GLSEN. (2020). The 2019 National School Climate Survey. New York, New York: GLSEN.Johns, M.M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L.C., Zewditu, D., McManus, T., et al. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school student–19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 65-71.Johns MM, Lowry R, Haderxhanaj LT, et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly, 69(Suppl-1):19–27. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3external Meyer, I. H. (2016). Does an improved social environment for sexual and gender minorities have implications for a new minority stress research agenda? Psychology of Sexualities Review, 7(1), 81-90.Michelmore, L., & Hindley, P. (2012). Help‐seeking for suicidal thoughts and self‐harm in young people: A systematic review. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 42(5), 507-524.The Trevor Project. (2020). Research Brief: LGBTQ & Gender-Affirming Spaces. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/2020/12/03/research-brief-lgbtq-gender-affirming-spaces/ |