Summary

LGBTQ youth are at elevated risk for suicide compared with their straight/cisgender peers (Johns et al, 2019; Johns et al., 2020). This risk stems from experiences of minority stress including victimization and rejection rather than something inherent about being LGBTQ (Meyer, 2003). Victimization and rejection from caregivers can also result in LGBTQ youth involvement in the foster care system (Newcomb et al., 2019), which is strongly associated with greater suicide risk among youth in general (Brown, 2020). Despite the overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth among those who have entered foster care (Baams, Russel, & Wilson 2019), there remains a lack of studies examining which subgroups of LGBTQ youth are most at risk of being in foster care as well as how a foster care history relates to suicide risk among LGBTQ youth. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2020 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief focuses on foster care and suicide risk among LGBTQ youth.

Results

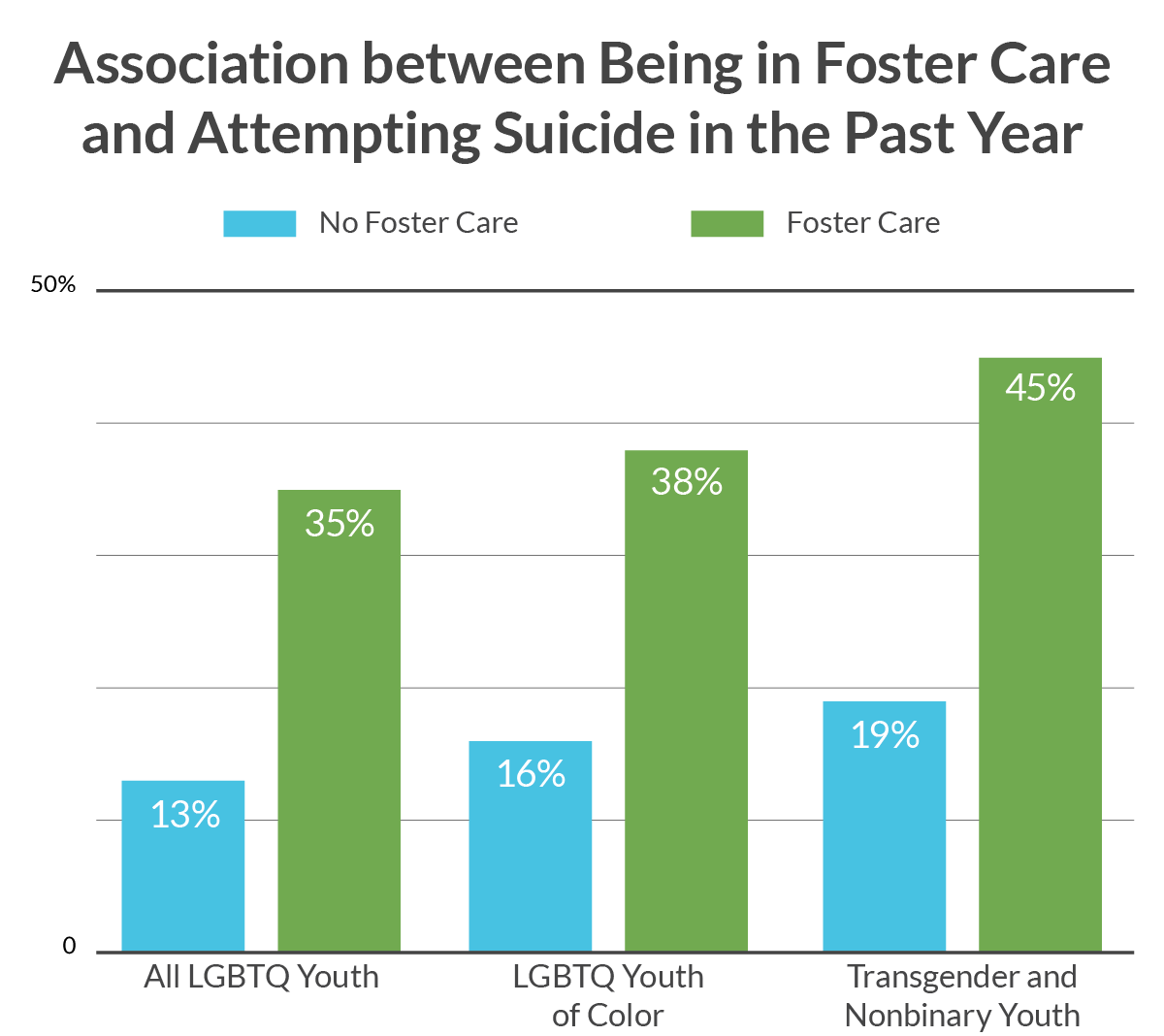

LGBTQ youth who reported having been in foster care had three times greater odds of reporting a past-year suicide attempt compared to those who had not (aOR=2.98, p<.001). Overall, 4.1% of LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 reported ever being in foster care compared to 2.6% among the general population of U.S. adults ages 18 and older (Nugent et al., 2020). Transgender and nonbinary youth had greater odds of being in foster care compared to cisgender LGBQ youth, with the greatest odds experienced by transgender girls/women (aOR=1.88, p<.001) followed by nonbinary youth (aOR=1.70, p<.001), and transgender boys/men (aOR=1.43, p<.001). LGBTQ youth of color also had significantly greater odds of being in foster care compared to White LGBTQ youth. Native/Indigenous LGBTQ youth had the greatest odds of experiencing foster care (aOR=5.25, p<.001), followed by multiracial LGBTQ youth (aOR=2.15, p<.001), Black LGBTQ youth (aOR=2.06, p<.001), Latinx LGBTQ youth (aOR=1.95, p<.001), and Asian/Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth (aOR=1.41, p=.01).

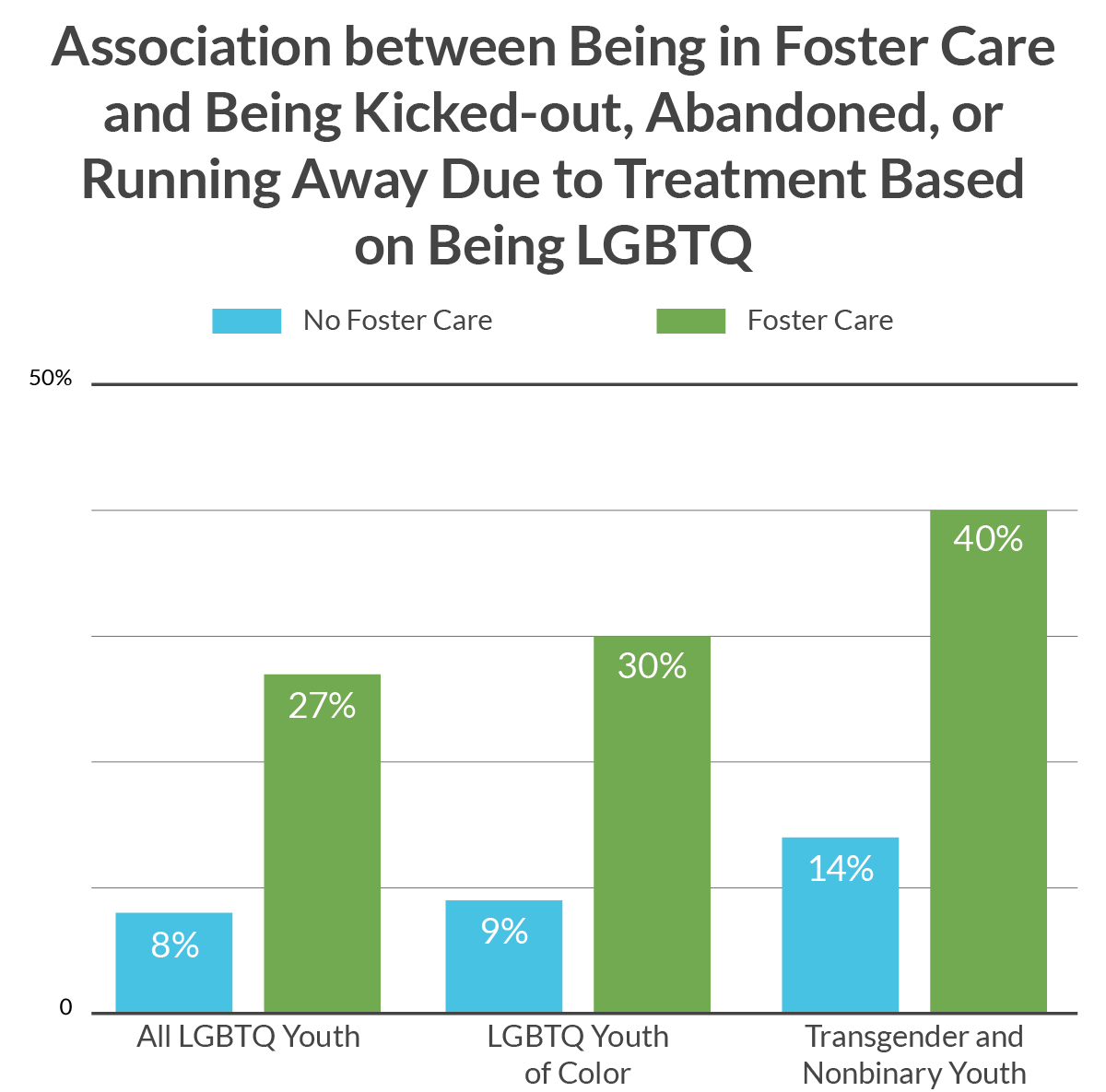

LGBTQ youth who had been in foster care had nearly four times greater odds of being kicked out, abandoned, or running away due to treatment based on their LGBTQ identity compared to those who were never in foster care (aOR=3.77, p<.001). Although all subgroups of LGBTQ youth in foster care had higher rates of being kicked out, abandoned, or running away due to treatment based on their LGBTQ identity, transgender and nonbinary youth had the highest rates. Overall, 40% of transgender and nonbinary youth in foster care reported being kicked out, abandoned, or running away due to treatment based on their LGBTQ identity compared to 17% of cisgender LGBQ youth in foster care.

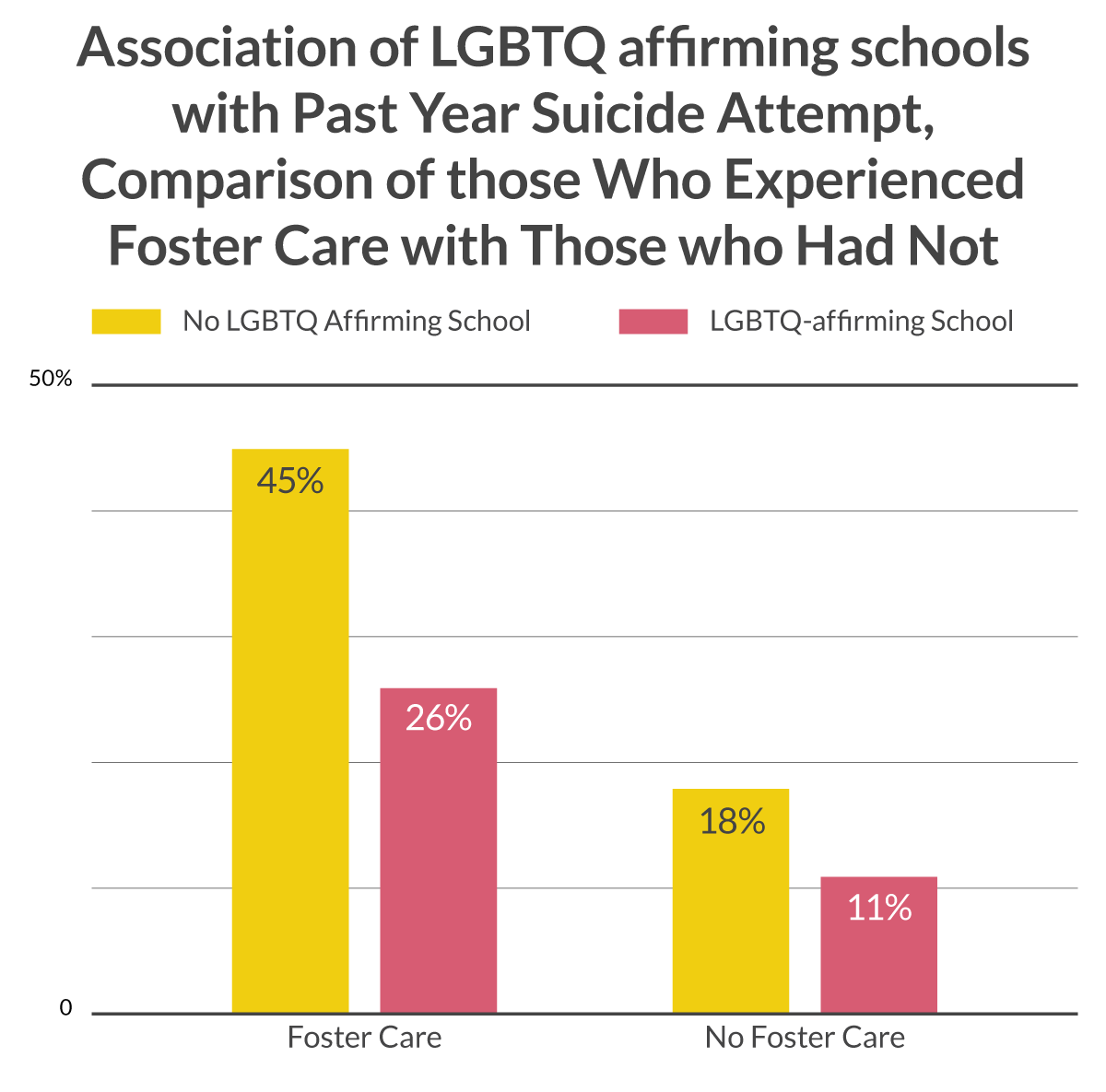

Among LGBTQ youth with a history of foster care, those who reported attending an LGBTQ-affirming school had more than 50% lower odds of reporting a past-year suicide attempt compared to those who attended a school that was not LGBTQ-affirming (aOR=0.45, p<.001). Overall, 45% of LGBTQ youth with a history of foster care who had a school that was not LGBTQ-affirming attempted suicide in the past year compared to 26% of those who had a school that was LGBTQ-affirming. Although LGBTQ-affirming schools were protective for LGBTQ youth in general, they had even greater protective effects for LGBTQ youth with a history of foster care compared to those who were never in foster care (aOR=0.63, p<.001).

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between December 2019 and March 2020 of 40,001 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. To assess lifetime involvement in foster care, youth were asked, “Have you ever been in foster care (even if only for a short period of time)?” Our question on attempted suicide (“During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”) was taken from the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey. A logistic regression model adjusting for age, gender identity, and race/ethnicity, was used to examine the association of foster care involvement with past-year attempted suicide. A separate adjusted logistic regression model was used to examine disproportionality in foster care history by age, gender identity, and race/ethnicity. Finally, logistic regression models adjusting for age, gender identity, and race/ethnicity were used to examine the association of youth reporting their schools to be LGBTQ-affirming with a past-year suicide attempt among those with a history of foster care and among those who were never in foster care.

Looking Ahead

LGBTQ youth have high rates of attempting suicide, and those who have been in foster care report attempting suicide at an even higher rate. Unfortunately, LGBTQ youth are disproportionately represented in the foster care system, with the highest rates found among LGBTQ youth of color and those who are transgender and nonbinary. Our data point to a strong association between foster care involvement and being kicked out, abandoned, or running away due to treatment based on one’s LGBTQ identity, particularly among transgender and nonbinary youth. Our data isn’t able to establish whether youth were kicked out, abandoned, or ran away prior to, during, or after being in foster care. However, the association between the two experiences highlights the important role supportive and accepting caregivers can play in helping LGBTQ youth remain outside the foster care system. Further, given the intersection of foster care and suicide risk among LGBTQ youth, there is a need for training in foster care and child welfare more broadly on how to best support those with LGBTQ identities. Child welfare agencies should establish policies for identifying and supporting LGBTQ youth in care, including developing practices to ensure foster care placements are LGBTQ-affirming. Notably, policies that prohibit same-sex caregivers from adoption and foster care may further place LGBTQ youth at risk, as these homes may be best able to provide them with the support, acceptance, and guidance they need.

Our data reflect similar patterns to national trends on the disproportionate involvement of youth of color in foster care, particularly those who are Black or Native/Indigenous (Puzzanchera & Taylor, 2020). These disparities stem in part from historical oppression such as forcibly removing Native children from their families and sending them to boarding schools (Gojevic, 2020) as well as structural and institutional racism that plays out in biased policies and practices that continue to oppress people of color in the U.S. (Dettlaff & Boyd, 2020). National conversations around racism should focus on ensuring our systems of care and policies designed to protect youth are actually allowing them to thrive rather than contributing to further oppression.

Finally, our data highlight the power of LGBTQ-affirming schools for all youth, but particularly for those who have a history of foster care. Such data point to the power of positive factors like affirmation and social support to buffer the impact of other negative experiences among LGBTQ youth. At The Trevor Project, our public education team provides training on supporting LGBTQ identities to organizations across the county, including those involved in the foster care system. Further, our advocacy and research teams leverage data to inform and improve policies and practices for all LGBTQ youth, particularly those who are placed at the highest risk for suicide. Finally, our crisis services team works 24/7 to provide affirmation and support for all LGBTQ youth in crisis.

| ReferencesBaams, L., Wilson, B. D., & Russell, S. T. (2019). LGBTQ Youth in Unstable Housing and Foster Care. Pediatrics, 143(3), e20174211.Brown, L. A. (2020). Suicide in foster care: a high-priority safety concern. Perspectives on psychological science, 15(3), 665-668.Dettlaff, A.J., & Boyd, R. (2020). Racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system: Why do they exist, and what can be done to address them?. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 692(1), 253-274.Gojevic, K. L. (2020). Benefit or Burden?: Brackeen v. Zinke and the Constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act. Buffalo Law Review, 68, 247.Johns, M.M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L.C., Zewditu, D., McManus, T., et al. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school student–19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR, 68(3), 65-71.Johns M.M., Lowry R., Haderxhanaj L.T., et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Suppl, 69,(Suppl-1):19–27.Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697.Newcomb, M. E., LaSala, M. C., Bouris, A., Mustanski, B., Prado, G., Schrager, S. M., & Huebner, D. M. (2019). The influence of families on LGBTQ youth health: A call to action for innovation in research and intervention development. LGBT health, 6(4), 139-145.Nugent C.N., Ugwu C., Jones .J, Newburg-Rinn S., & White T. (2020). Demographic, health care, and fertility-related characteristics of adults aged 18–44 who have ever been in foster care: United States, 2011–2017. National Health Statistics Reports; no 138. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.Puzzanchera, C. and Taylor, M. (2020). Disproportionality Rates for Children of Color in Foster Care Dashboard. National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. Available at: https://ncjj.org/AFCARS/Disproportionality_Dashboard.aspx Accessed on April 12, 2021. |

For more information please contact: [email protected]