Background

Nearly 3% of children and adolescents ages 13-17 and an estimated 2% of adults ages 18-84 have been diagnosed with Autism (clinically referred to as Autism Spectrum Disorders) (Xu et al., 2018; Dietz et al., 2020). In recent years, both scholarship and activism from autistic individuals have shifted the conceptualization of autism away from a developmental disability framework and toward a neurodiversity framework, which recognizes Autism as a different but equally valid way of engaging with and experiencing the world (Happé & Frith, 2020). Autistic individuals report poorer mental health than individuals without autism, who are commonly referred to as “allistic.” Autistic youth report higher rates of depression (Pezzimenti et al., 2019) and anxiety (Zaborski & Storch, 2017) than their allistic peers. Rates of dying by suicide are also higher for autistic individuals than for their allistic peers (Hirvikoski et al., 2016). Aligning with the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), these mental health outcomes may be due to the stress of trying to navigate a world with a stigmatized identity. There is also growing evidence to suggest that autistic individuals are more likely to identify as LGBTQ (Dewinter et al., 2017), and autistic individuals report high levels of gender non-conforming feelings (Dewinter et al., 2017). Further, the prevalence of autism among individuals with gender dysphoria is estimated to be between 6%-25% (Thrower et al., 2019). While there is less research on the mental health of individuals living at the intersection of autism and LGBTQ identities, autistic LGBTQ adults report higher levels of barriers to healthcare, unmet healthcare needs, self-reported mental illness, and being refused services by a medical provider than their allistic peers (Hall et al., 2020). Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief examines mental health and suicide risk among autistic LGBTQ youth.

Results

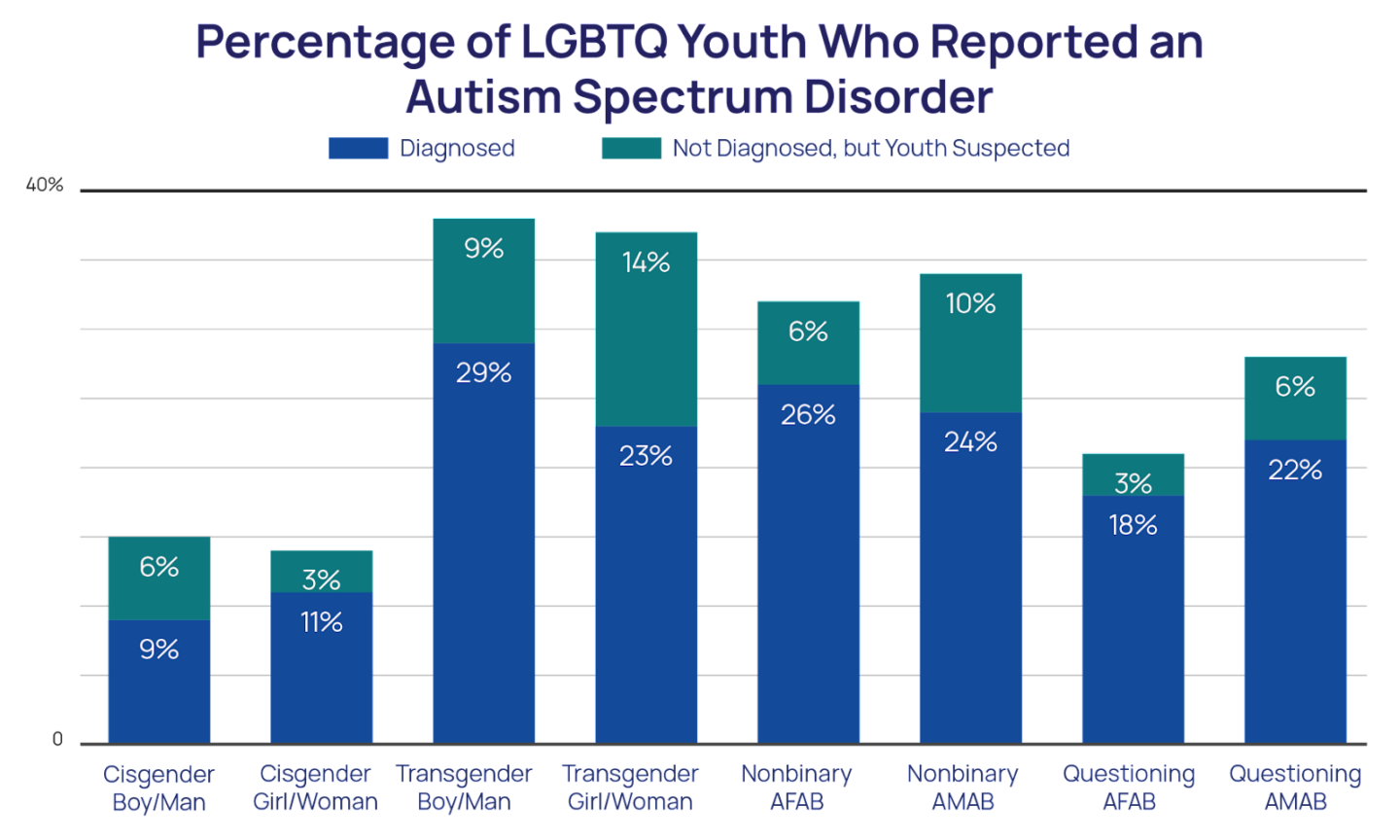

Overall, 5% of LGBTQ youth have been diagnosed with autism. Additionally, 35% suspect they might be autistic. Transgender girls/women (14%) and nonbinary youth assigned male at birth (AMAB) (10%) had the highest diagnosis rates. Transgender boys/men (29%) and nonbinary youth assigned female at birth (AFAB) (26%) had the highest rates of suspecting they are autistic. Cisgender girls/women (3%) reported the lowest rates of being diagnosed with autism, and cisgender boys/men (9%) reported the lowest rates of suspecting they are autistic.

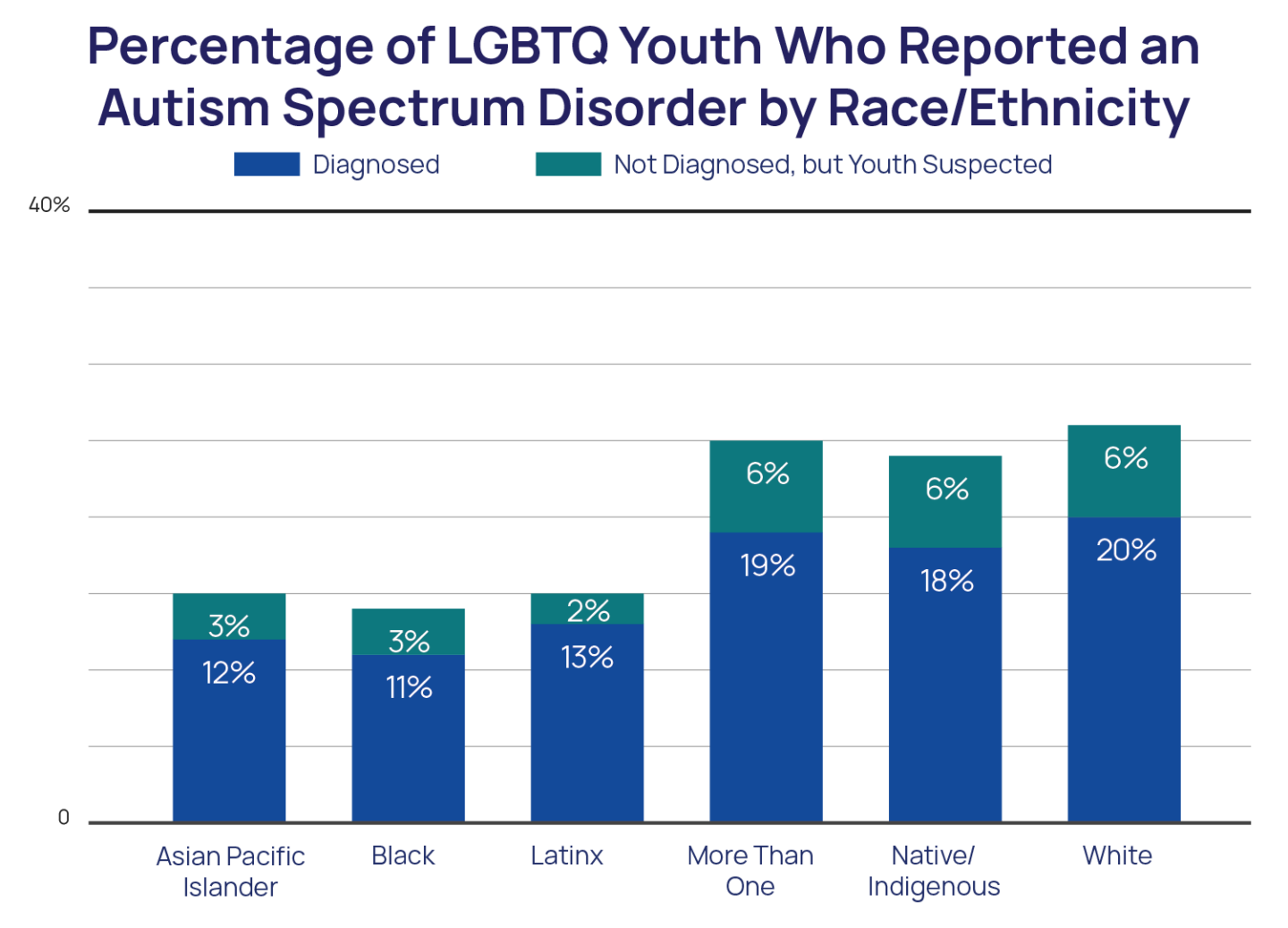

Native/Indigenous, Multiracial, and White LGBTQ youth reported double the rate (6%) of being diagnosed with autism compared to Asian/Pacific Islander (3%), Black (3%), and Latinx (2%) LGBTQ youth. White (20%), Multiracial (19%), and Native/Indigenous (18%) youth also reported higher rates of suspecting they are autistic than Latinx (13%), Asian/Pacific Islander (12%), and Black (11%) LGBTQ youth.

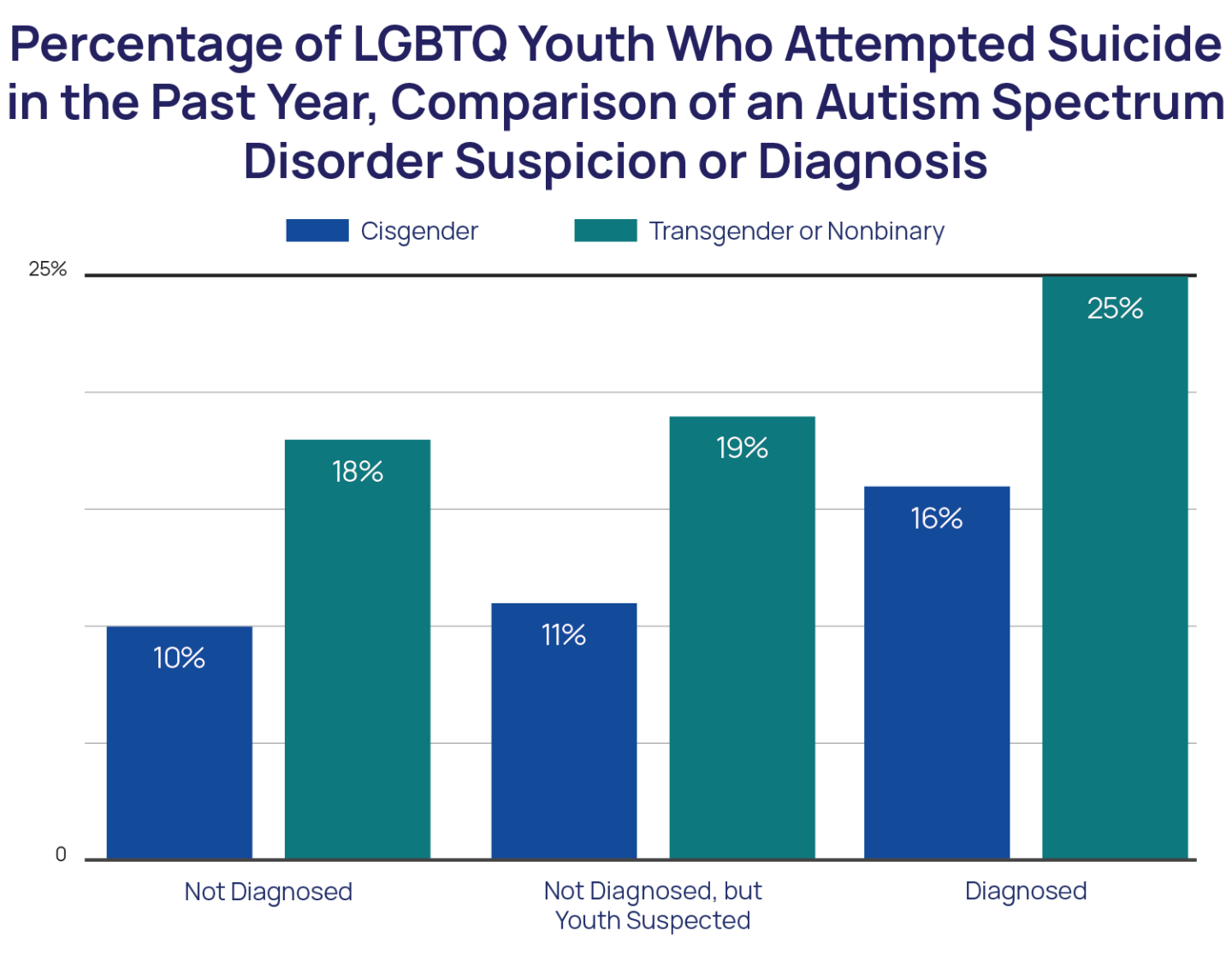

LGBTQ youth who have ever been diagnosed with autism had over 50% (aOR=1.59) greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year compared to those who have never been diagnosed with autism. Both youth who had been diagnosed with autism (aOR = 1.30) and youth who suspected that they may be autistic (aOR = 1.12) had slightly greater odds of seriously considering suicide in the last year. Youth who suspected that they may be autistic reported the highest rates of anxiety (79%) and depression (71%) compared to both youth who have autism diagnoses and those who do not. However, youth who had been diagnosed with autism also reported higher rates of recent anxiety (77%) and depression (66%) compared to youth who had never been diagnosed with autism (69% and 60%, respectively).

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between October and December 2020 of 34,759 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. To assess self-reported autism, youth were asked, “Have you ever been diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum?” with response options of 1) No, 2) No, but I think I might be, and 3) Yes. Our item on attempting suicide in the past 12 months was taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). An adjusted logistic regression model was conducted to determine the association between autism suspicion or diagnosis and a past-year suicide attempt while controlling for age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual identity.

Looking Ahead

Although data from our non-probability sample are unable to estimate national prevalence rates, the findings align with scholarship suggesting that the rates of autistic individuals appear to be higher among LGBTQ people (Dewinter et al., 2017). Further, 35% of youth in our study reported that they suspected they may be autistic despite never being diagnosed. Our findings also align with scholarship that has found autism to be underdiagnosed among girls and women (Garb, 2021; Lockwood Estrin et al., 2020). Research on autism has historically focused on cisgender boys, and more scholarship is needed to understand how autism presents among people of other genders and among adults. Cisgender girls/women in our sample report the lowest rates of being diagnosed with autism. Additionally, transgender boys/men and nonbinary youth assigned female at birth – who are not girls or women but may have been perceived, and therefore treated, as such by medical providers at various points in their life – report the highest rates of suspecting they may be autistic, but relatively low rates of diagnosis. Our findings also show racial disparities, with Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, and Latinx youth reporting lower rates of both suspecting and being diagnosed with autism compared to their white peers. More research is needed to understand these disparities, but they may be indicative of historic underdiagnoses among communities of color (Garb, 2021). Finally, these findings align with scholarship about elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide risk among autistic individuals (Pezzimenti et al., 2019; Zaborski & Storch, 2017; Hirvikoski et al., 2016). LGBTQ youth in our sample who had been diagnosed with autism had over 50% greater odds of attempting suicide in the last year compared to their allistic LGBTQ peers. These findings highlight the urgent need for mental health providers to offer both LGBTQ-affirming and autism-affirming counseling services to autistic LGBTQ youth. Particular attention should be paid to developing and implementing mental health and suicide assessments that are inclusive of autistic youths’ unique needs.

The Trevor Project is committed to finding ways for all LGBTQ youth to feel safe and supported. Our 24/7 crisis services are available in three different modalities – phone, chat, and text – so that youth in crisis have multiple avenues to communicate with culturally competent and affirming adults. Our TrevorSpace platform also connects youth with supportive peers. Further, Trevor’s research, advocacy, and education teams are focused on using data, policies, and education to enhance the ability of youth-serving professionals to understand and address these young people’s mental health needs.

References

- Dietz, P. M., Rose, C. E., McArthur, D., & Maenner, M. (2020). National and state estimates of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4258–4266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04494-4

- Dewinter, J., De Graaf, H., & Begeer, S. (2017). Sexual orientation, gender Identity, and romantic relationships in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47:2927–2934

- Garb, H. N. (2021). Race bias and gender bias in the diagnosis of psychological disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 90, 102087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102087

- Hall, J. P., Batza, K., Streed, C. G., Boyd, B. A., & Kurth, N. K. (2020). Health Disparities Among Sexual and Gender Minorities with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(8), 3071–3077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04399-2

- Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2020). Annual research review: Looking back to look forward – changes in the concept of autism and implications for future research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(3), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13176

- Hirvikoski, T., Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., Boman, M., Larsson, H., Lichtenstein, P., & Bölte, S. (2016). Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(3), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192

- Lockwood Estrin, G. (2021). Barriers to autism spectrum disorder diagnosis for young women and girls: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8, 454–470.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697.

- Pezzimenti, F., Han, G. T., Vasa, R. A., & Gotham, K. (2020). Depression in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 28(3): 397–409

- Thrower, E., Bretherton, I., Pang, K. C., Zajac, J. D., & Cheung, A. S. (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Amongst Individuals with Gender Dysphoria: A Systematic Review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(3), 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04298-1

- Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Corrected Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among US Children and Adolescents. JAMA, 319(5), 505. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0001

- Zaboski, B. A., & Storch, E. A. (2018). Comorbid autism spectrum disorder and anxiety disorders: A brief review. Future Neurology, 13(1), 31–37.

Acknowledgments: The Trevor Project thanks Maddie Chumley-Jones and Ren Brady Pleasants for their time and expertise in reviewing this Brief.

For more information, please contact: [email protected]