Background

An estimated 1.76 million young people in the United States have a parent in the military (Sogomonyan & Cooper, 2010). Military-connected youth have unique stressors due to their parents’ military service, including but not limited to: frequent moves, separations for deployments or training, and fear of harm of the military member (Gyura & McCauley, 2016). Likely due to these stressors, youth with military parents are more likely to report depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation than their peers without military parents (Cederbaum et al., 2013). Youth who report that a parent or sibling had deployed also reported higher odds of experiencing sadness, hopelessness, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation compared to youth who reported no family deployments (Cederbaum et al., 2013). There is a small but growing body of literature about the intersection of LGBTQ identity and family military connections among youth, with especially little information about their mental health. LGBTQ youth with military parents face even more challenges compared to their straight and cisgender peers, as well as their LGBTQ peers without parents in the military. These challenges can include trying to find an LGBTQ-affirming community, or having to come out repeatedly with each frequent move (Oswald & Sternberg, 2014). LGBTQ youth with military parents are also more likely to report substance use than heterosexual youth with military parents (De Pedro & Shim-Pelayo, 2018). Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief seeks to add to the literature by examining mental health and suicide risk among LGBTQ youth with a parent currently in the military.

Results

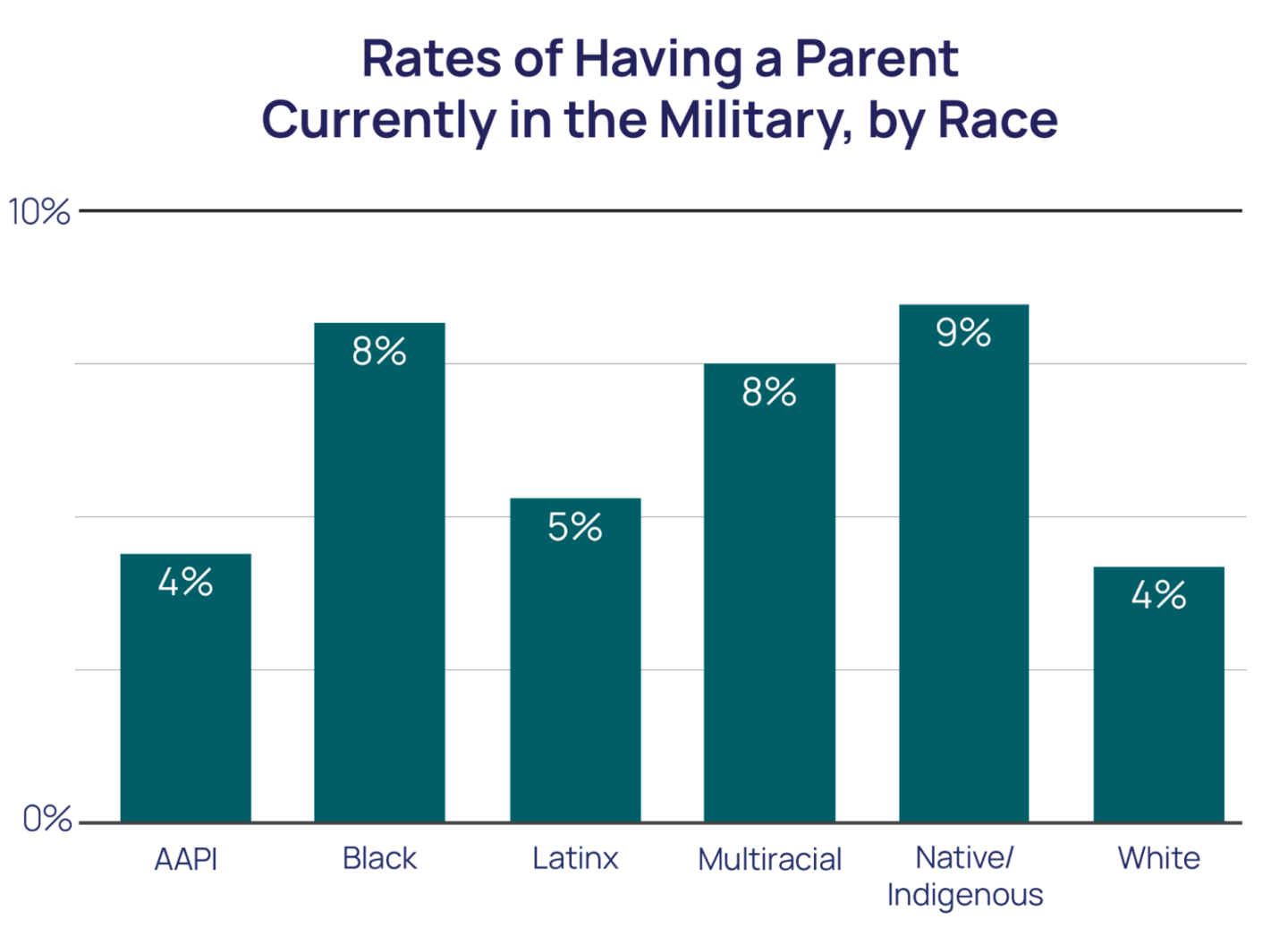

Overall, 5% of LGBTQ youth in our sample reported having a parent currently in the military. Significantly more LGBTQ youth under age 18 reported having a parent currently in the military (7%) compared to LGBTQ youth ages 18 to 24 (4%). LGBTQ youth living in the South reported the highest rates of having a parent currently in the military (7%) compared to LGBTQ youth living in the Northeast (4%), Midwest (4%), and West (5%). LGBTQ youth who are Native/Indigenous (9%), Black (8%), or multiracial (8%) reported the highest rates of having a parent currently in the military.

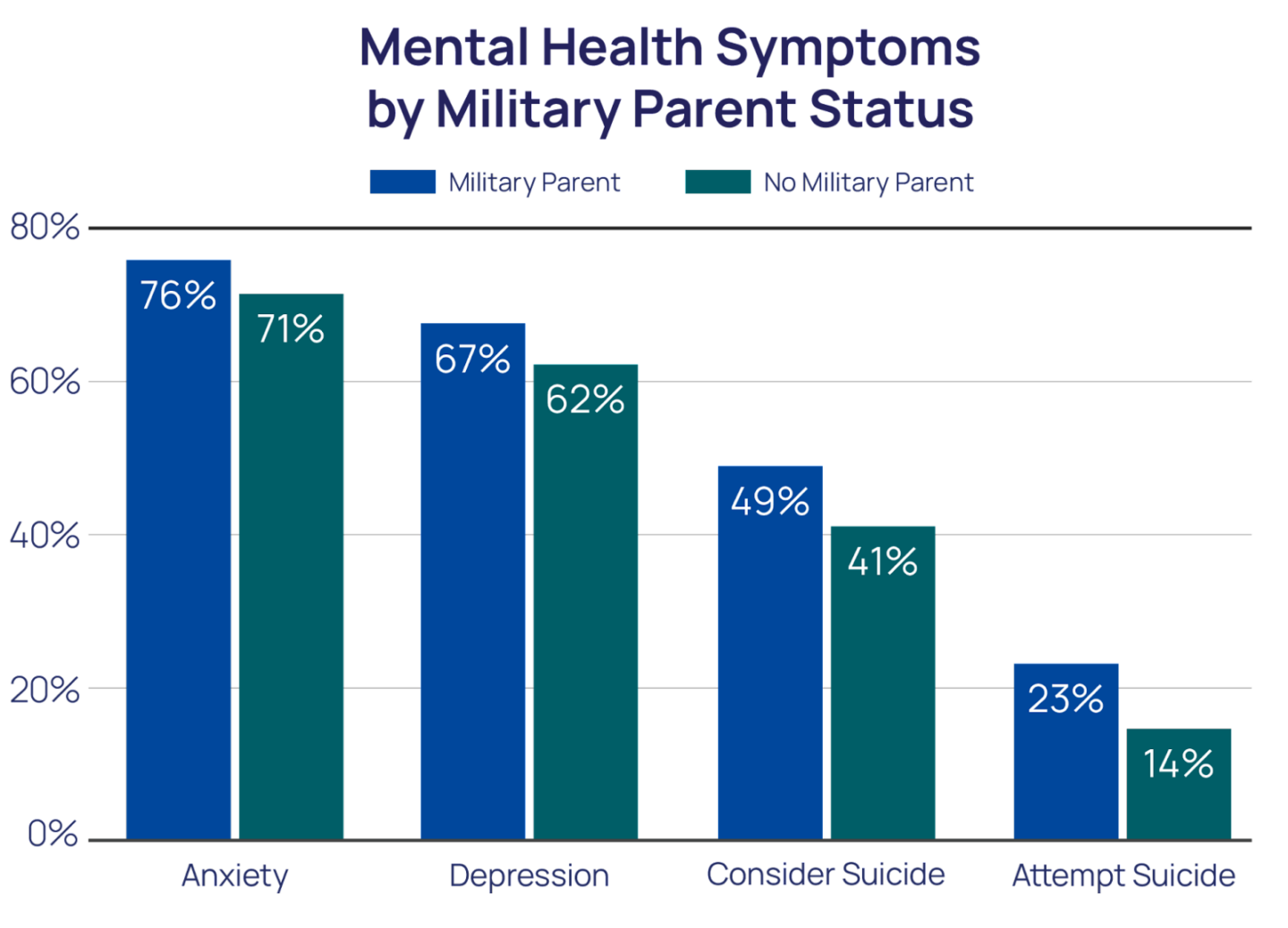

LGBTQ youth who reported having a parent currently in the military reported significantly higher rates of mental health challenges and suicide risk. Among the full sample, having a parent currently in the military was associated with 17% higher odds of recent anxiety symptoms (aOR = 1.17), 14% higher odds of seriously considering suicide in the past year (aOR = 1.14), and nearly 40% higher odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 1.39) after controlling for demographic variables. Mental health issues were particularly common among LGBTQ youth under 18 who reported having a parent currently in the military. Among LGBTQ youth under age 18, having a parent currently in the military was associated with 34% higher odds of recent anxiety symptoms (aOR = 1.34), nearly 20% higher odds of recent depression symptoms (aOR = 1.19), 17% higher odds of considering suicide (aOR = 1.17), and 36% higher odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 1.36). Among LGBTQ youth ages 18 to 24, having a parent currently in the military was associated with 45% higher odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 1.45), and was not significantly associated with anxiety, depression, or considering suicide in the past year.

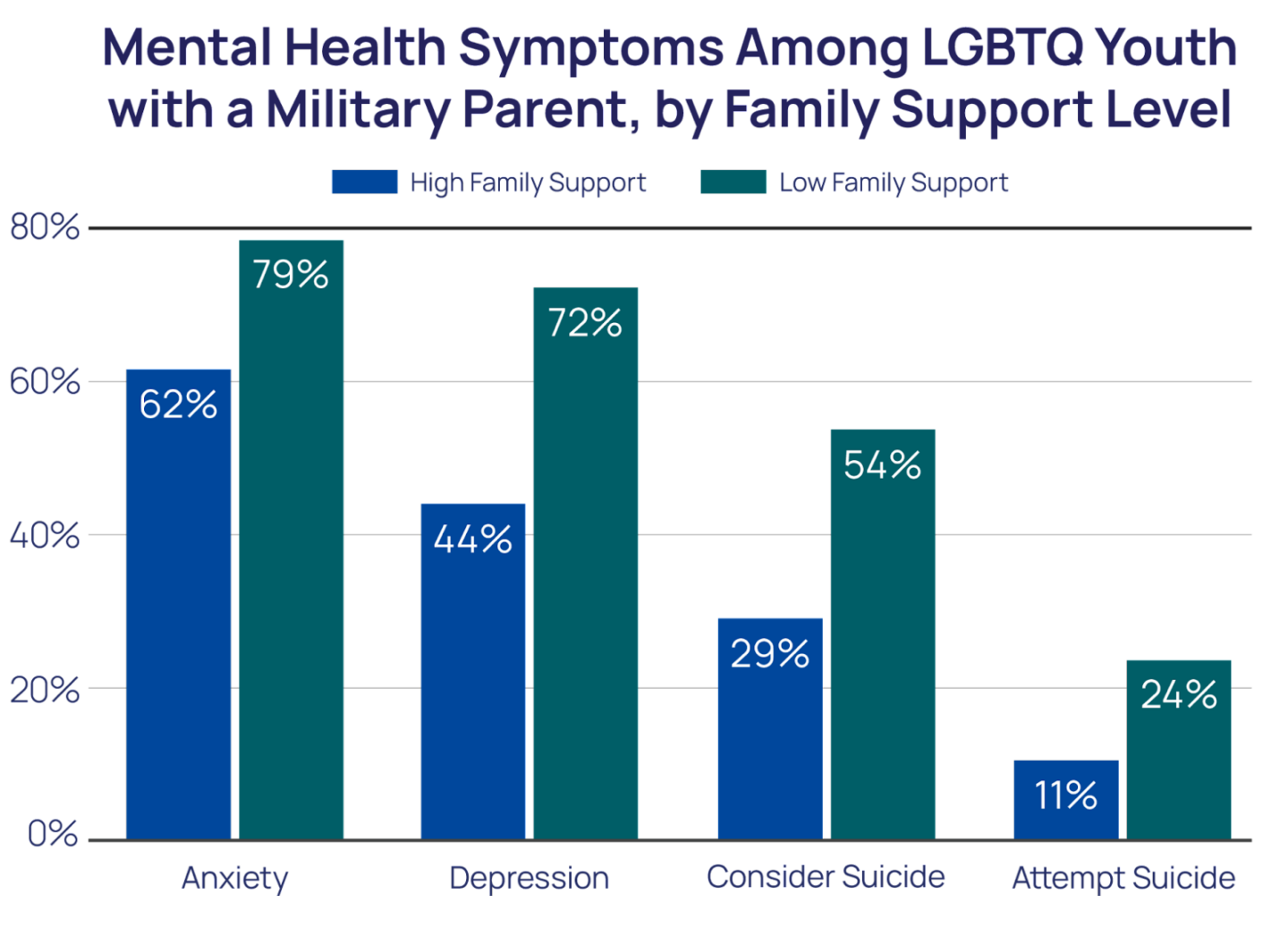

LGBTQ youth with a parent currently in the military who reported high levels of family support had lower mental health challenges and suicide risk. LGBTQ youth with a parent currently in the military reported having high levels of family support at similar rates (22%) compared to their LGBTQ peers without a parent currently in the military (23%). Among LGBTQ youth with a parent currently in the military, having high levels of family support was associated with nearly 40% lower odds of recent anxiety symptoms (aOR = 0.61), 56% lower odds of recent depression symptoms (aOR = 0.44), and 46% lower odds of considering suicide in the past year (aOR = 0.54).

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between October and December 2020 of 34,759 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. To assess whether youth have a parent currently in the military, youth were asked, “Do you have a parent or caregiver who is currently in the military (Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, National Guard, or Reserves)?” with response options of 1) No, 2) Yes, and 3) I don’t know. Our item on attempting suicide in the past 12 months was taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Adjusted logistic regression models were conducted to determine the association between having a parent currently in the military and recent anxiety symptoms, recent depression symptoms, seriously considering suicide in the past year, and attempting suicide in the past year, while controlling for age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual identity, and census region.

Looking Ahead

These data illuminate the disproportionate mental health challenges and suicide risk experienced by LGBTQ youth with parents currently in the military. LGBTQ youth under age 18 reported higher rates of having a parent currently in the military than their LGBTQ peers over age 18. LGBTQ youth living in the South reported higher rates of having a parent currently in the military than those in other census regions, and LGBTQ youth who are Native/Indigenous, Black, or Multiracial reported the highest rates of having a parent currently in the military compared to other racial groups. These racial disparities echo pre-existing data on racial demographics in the military, which show that people of color are overrepresented compared to their White peers in some branches (Council on Foreign Relations, 2020). LGBTQ youth with a parent currently in the military were more likely to report anxiety, considering suicide, and attempting suicide in the past year compared to their LGBTQ peers who do not have parents currently in the military. Risks are particularly high for youth under the age of 18, who in both military and non-military families are more reliant on their parents or caregivers for support. These findings also highlight the important role of family support. LGBTQ youth with military parents who report high levels of family support report lower rates of anxiety, depression, and considering suicide in the past year. Family support can take many forms, from being available to talk about problems in a young person’s life, to being open to their LGBTQ friends, to using the correct name and pronouns.

When interpreting these results, it is important to acknowledge and consider the vast diversity of experiences that youth with military parents represent. Our data do not have details about whether or not the youths’ military parent is active-duty or a reservist, which can involve different levels of disruption to family life. We also do not know if youths’ parents have deployed, or if their families live on a military base. Different military family experiences (e.g. having only one or multiple parents in the military, having a parent in the reserves or in active-duty, living on a base or not) may be associated with different levels of mental health risk. Future research should examine these differences in experience across military families. Despite these limitations,, these findings have important implications for military families and those who serve them. Mental health providers working with military families must be LGBTQ-affirming and culturally competent. Providers working on military bases or with TRICARE (the healthcare program for service members and their families) should provide LGBTQ competency training for all of their staff. Additionally, mental health providers not explicitly connected to the military must be prepared to understand the impact that a parent’s military service can have on their child’s mental health, especially for youth who are not living on or connected to military bases and services and whose military connections and stressors may not be as apparent (Gyura & McCauley, 2016). With the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell in 2010 and the removal of transgender military exclusion policies in 2021, inclusion of out and open LGBTQ service members is still a relatively new phenomenon. While 86% of LGBTQ service members report that their leadership is willing to acknowledge their spouse or partner, 62% also report that military family support resources did not meet the needs of LGBT families (Sullivan et al., 2021). The military itself, and organizations dedicated to supporting the mental health of service members and their families – especially in the area of suicide prevention – should actively take into account the needs of LGBTQ people and create welcoming and affirming spaces for families with LGBTQ members.

The Trevor Project is committed to finding ways for all LGBTQ youth to feel safe and supported. Our 24/7 crisis services are available in three different modalities – phone, chat, and text – so that youth in crisis have multiple avenues to communicate with culturally competent and affirming adults. We offer guides and resources for parents who want to learn more about how to support their LGBTQ children on our website. Our TrevorSpace platform also connects youth with supportive peers. Further, Trevor’s research, advocacy, and education teams are focused on using data, policies, and education to enhance the ability of youth-serving professionals to understand and address these young people’s mental health needs.

References

- Cederbaum, J. A., Gilreath, T. D., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., Pineda, D., DePedro, K. T., Esqueda, M. C., & Atuel, H. (2014). Well-being and suicidal ideation of secondary school students from military families. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(6), 672–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.006

- Council on Foreign Relations. (2020, July 13). Demographics of the U.S. military. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/demographics-us-military

- De Pedro, K. T., & Shim-Pelayo, H. (2018). Prevalence of substance use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in military families: Findings from the California Healthy Kids Survey. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(8), 1372–1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1409241

- Gyura, A. N., & McCauley, S. O. (2016). The whole family serves: Supporting sexual minority youth in military families. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 30(5), 414–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.10.006

- Oswald, R. F., & Sternberg, M. M. (2014). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual military families: Visible but legally marginalized. In S. MacDermid Wadsworth & D. S. Riggs (Eds.), Military deployment and its consequences for families (pp. 133-147). Springer.Sogomonyan, F., & Cooper, J. (2010). Trauma faced by children of military families: What every policymaker should know. National Center for Children in Poverty. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8HX1NDM

- Sullivan, K. S., Dodge, J., McNamara, K. A., Gribble, R., Keeling, M., Taylor-Beirne, S., Kale, C., Goldbach, J. T., Fear, N. T., & Castro, C. A. (2021). Perceptions of family acceptance into the military community among U.S. LGBT service members: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 7(s1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.3138/jmvfh-2021-0019

For more information, please contact: [email protected]