Background

Despite overall rates of suicidality among young people trending downward for the past 30 years, Black young people have experienced an increase in suicide attempts (Lindsey et al., 2019), with suicide rates among Black young people increasing 37% between 2018 and 2021 (Stone & Mack, 2023). Due to the already existing higher rates of suicide among transgender and nonbinary young people (Johns et al., 2019), even in comparison to their cisgender lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, and questioning (LGBQ) peers, the intersection of being both Black and transgender or nonbinary may make young people more susceptible to negative experiences and chronic stress stemming from their multiple marginalized social statuses (Bowleg & Bauer, 2014; Jones & Neblett, 2017). While studies have demonstrated this in samples of transgender and nonbinary young people of color (Chan et al., 2022; Vance et al., 2021), research has largely failed to explore the mental health of Black transgender and nonbinary young people. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief seeks to expand our understanding of Black young people’s mental health by specifically exploring mental health indicators and protective factors among Black transgender and nonbinary young people.

Results

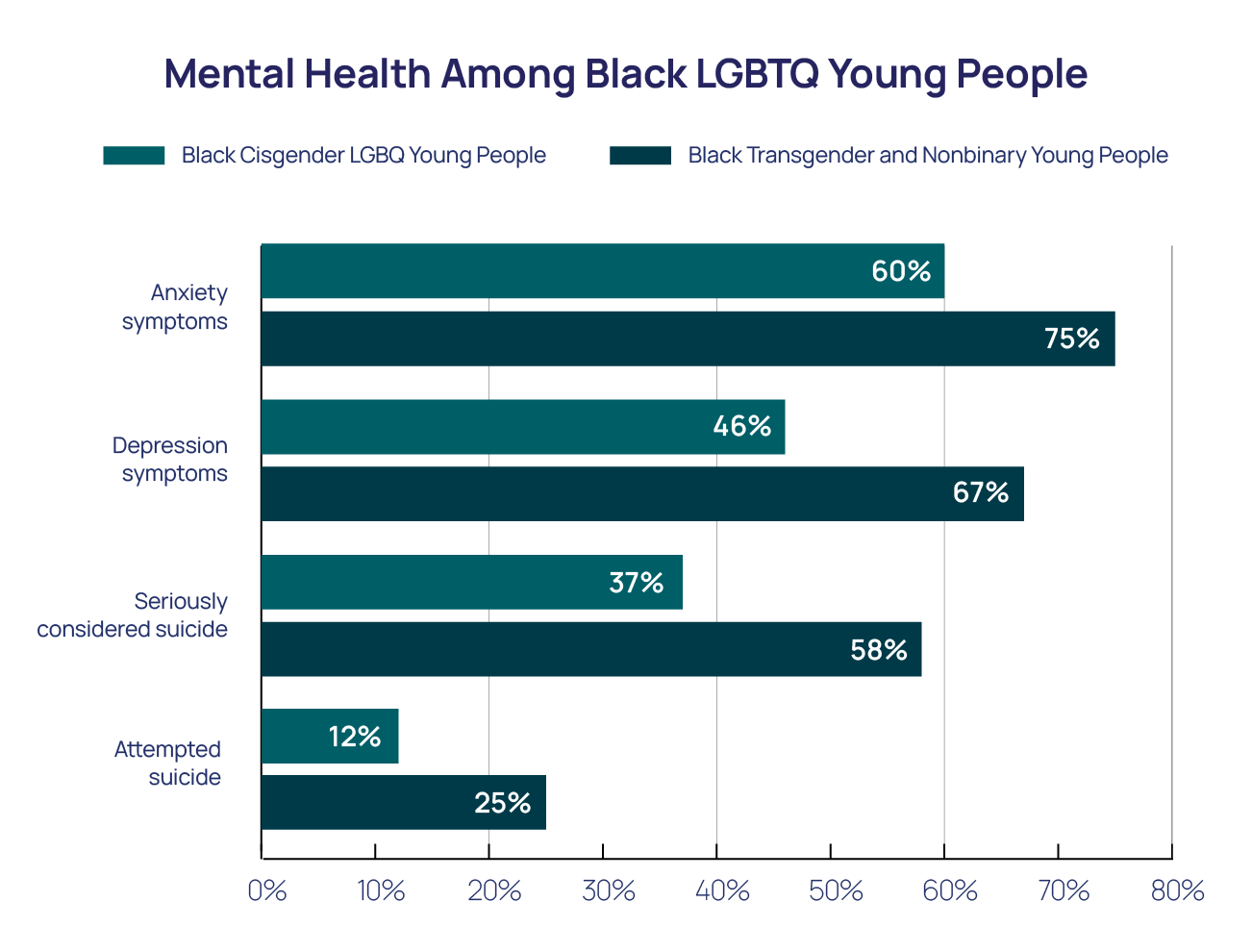

One in four (25%) Black transgender and nonbinary young people reported a suicide attempt in the past year. Nearly 3 in 5 (57%) Black LGBTQ young people identified as transgender or nonbinary, 11% of whom were transgender. Black transgender and nonbinary young people reported higher rates of all indicators of poor mental health compared to their Black cisgender LGBQ peers. This includes reporting more than double the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (25%) compared to Black cisgender LGBQ young people (12%). Among Black transgender and nonbinary young people, those who were assigned female at birth reported higher rates of both seriously considering suicide in the past year (60%) and attempting suicide in the past year (26%) compared to Black transgender and nonbinary young people assigned male at birth (43% and 18%, respectively), similar to overall patterns among transgender and nonbinary young people. There were no significant differences between Black young people who were transgender and Black young people who were nonbinary in any assessed mental health indicators.

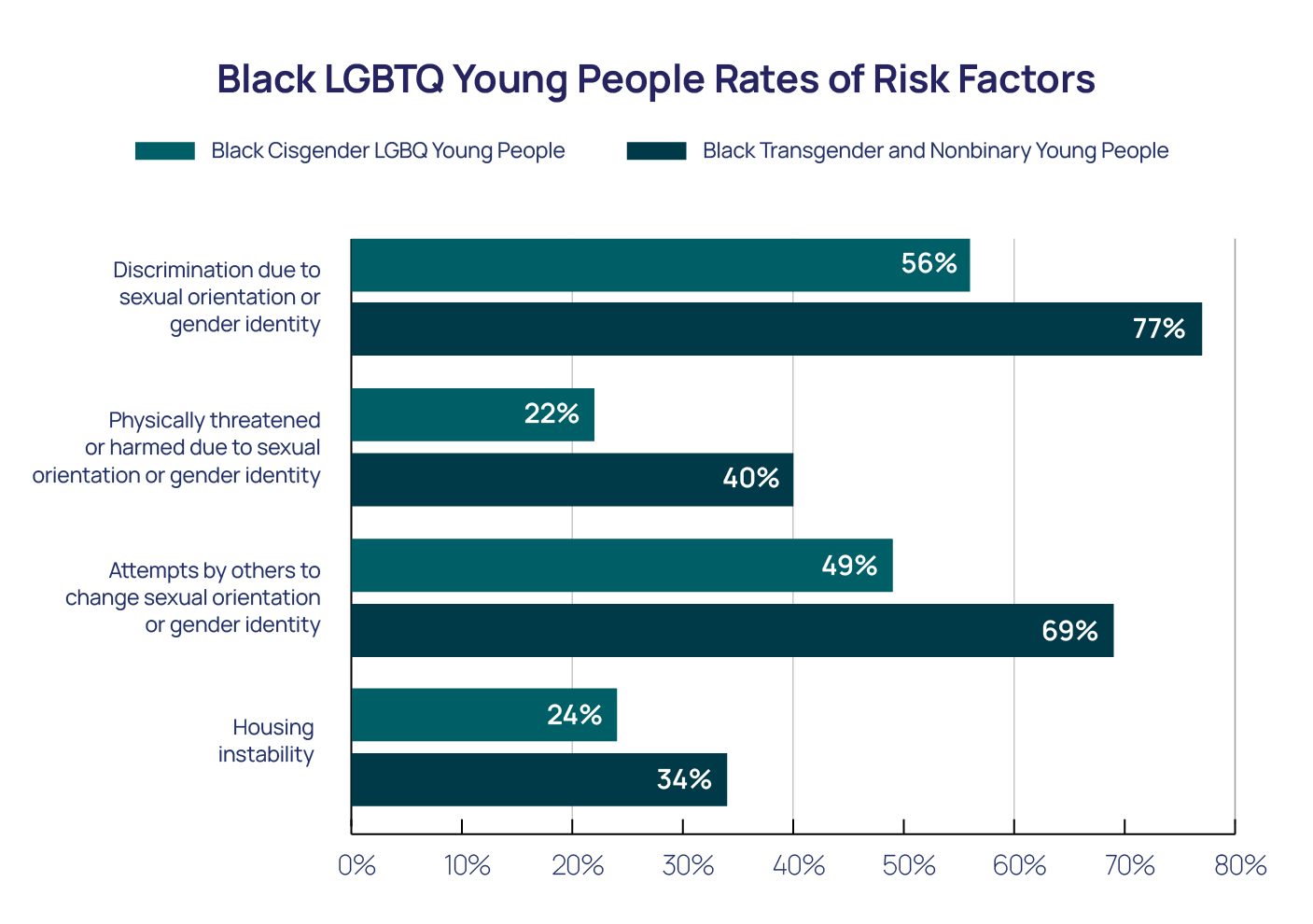

Black transgender and nonbinary young people experience higher rates of victimization, attempts from others to change their sexual orientation or gender identity, and housing instability compared to Black cisgender LGBQ young people. Black transgender and nonbinary young people reported higher rates of having ever experienced discrimination (77%) based on their sexual orientation or gender identity compared to Black cisgender LGBQ young people (56%). Additionally, Black transgender and nonbinary young people reported nearly double the rate of having been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity (40%) compared to Black LGBQ young people who were cisgender (22%). Importantly, both groups reported comparable rates of racial discrimination in the past year (60% vs 59%). Sixty-eight percent (68%) of Black transgender and nonbinary young people experienced having someone attempt to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity, compared to less than half of Black cisgender LGBQ young people (49%). Parents (45%) and non-LGBTQ friends (27%) were the most common people who attempted to convince Black transgender and nonbinary young people to change. Finally, 34% of Black transgender and nonbinary young people reported ever experiencing homelessness, being kicked out, or running away from home compared to 24% of Black cisgender LGBQ young people.

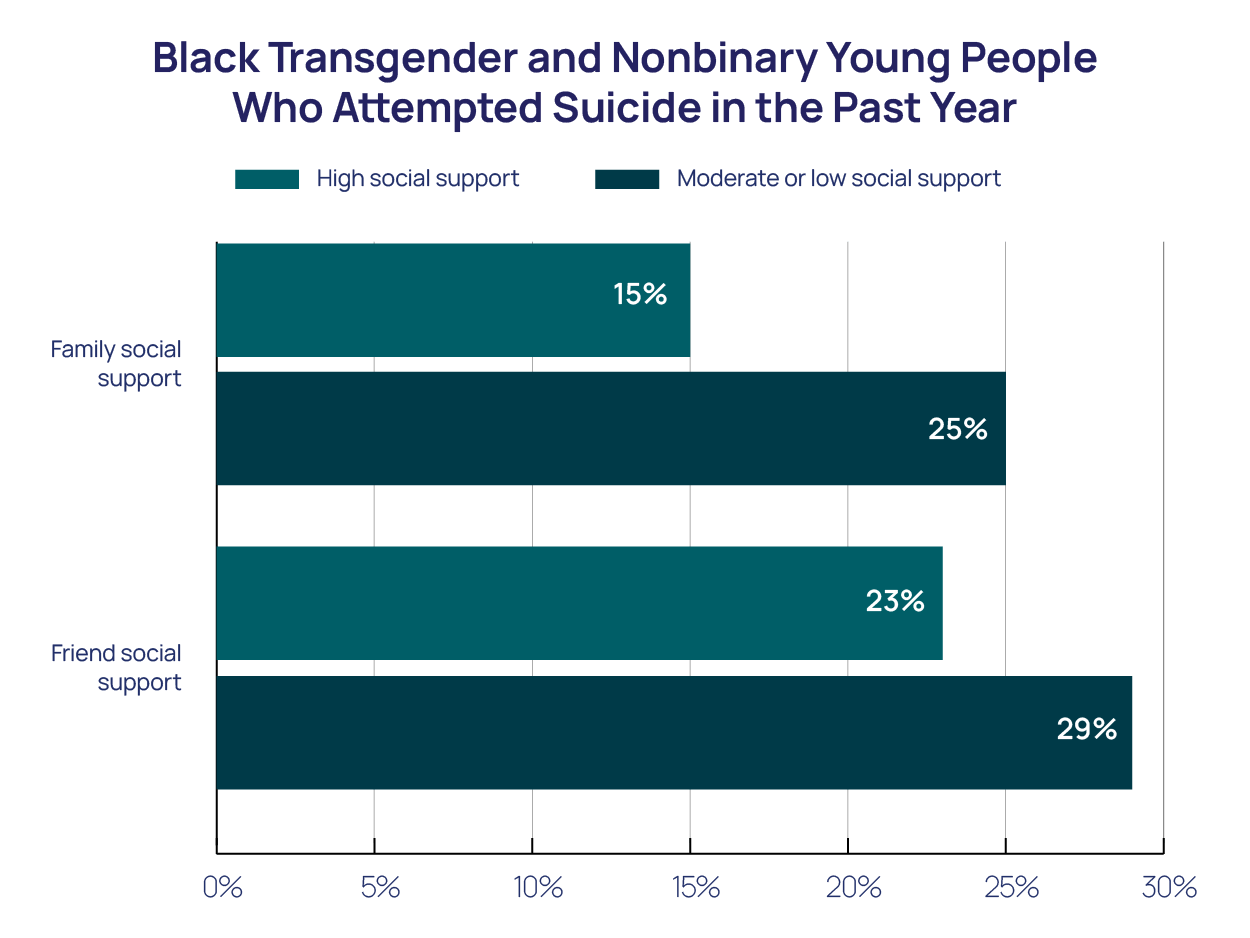

Black transgender and nonbinary young people with high social support from their family had 47% lower odds of reporting a suicide attempt in the past year (aOR=0.53, 95% CI [.31, .91]). Black transgender and nonbinary young people who reported high social support from their family (e.g., “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family”) reported lower rates of suicide attempts in the past year (15%) compared to Black transgender and nonbinary young people with low or moderate levels of support (26%). That said, only 13% of Black transgender and nonbinary young people reported high social support from family. In comparison, 72% of Black transgender and nonbinary young people had high social support from friends, which is also associated with 39% lower odds of a suicide attempt in the past year (aOR= 0.61, 95% CI [.43, .85]).

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2021 of 33,993 LGBTQ young people recruited via targeted ads on social media. In the survey, young people were asked “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, White/Caucasian, more than one race or ethnicity, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Young people who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question, “You said that you belong to more than one racial/ethnic group. With which of the following racial/ethnic groups do you most closely identify? Please select all that apply,” with all of the same response options. As there were no significant differences in reported mental health indicators between young people who identified as exclusively Black and multiracial Black, the current analyses include the 3,008 LGBTQ young people who either only identified as Black/African American or who identified as multiracial Black/African American, referred to throughout this brief as Black. Recent anxiety was assessed using the GAD-2 (Plummer et al., 2016), and recent depression was assessed using the PHQ (Richardson et al., 2010). Items measuring seriously considering and attempting suicide in the past 12 months were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Chi-square tests were used to examine differences between groups. All reported comparisons are statistically significant at least at p<0.05. This means there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance. Adjusted logistic regression models were run to determine the association between social support and attempting suicide in the past year among Black transgender and nonbinary young people, controlling for sex assigned at birth, sexual identity, and socioeconomic status.

Looking Ahead

The mental health of Black transgender and nonbinary young people is a public health crisis that deserves immediate attention from stakeholders across the board. Black transgender and nonbinary young people not only report higher rates of suicide attempts in the past year when compared to their Black cisgender LGBQ peers, but rates that are also significantly higher than their White transgender and nonbinary counterparts (16%). As illustrated in these findings, Black transgender and nonbinary young people must contend with stressors that are at the unique intersection of their race/ethnicity and gender. Given prior research on Black LGBTQ young people’s mental health (Price-Feeney et al., 2020), these additional stressors, on top of stressors faced by all young people, contribute to higher rates of attempting suicide among this marginalized group.

Although Black transgender and nonbinary young people face additional challenges, we also found that social support can help mitigate their negative impact. Black transgender and nonbinary young people may be benefiting from family social support in the same way that Black family racial socialization, or specific messages passed to younger generations about the meaning and importance of race and interconnectivity, is protective against racism (Lesane-Brown, 2006). Therefore, Black families should not only be encouraged to support their transgender and nonbinary young people by interweaving overtly supportive messages around gender identity into their existing family support structure, but they should also be provided with the necessary structural and educational resources to empower them to show up as best as they can for the young LGBTQ people in their lives. This includes prioritizing Black transgender and nonbinary well-being among youth-serving organizations, mental health professionals, and research endeavors. They also suggest that family members and friends be brought into any efforts to both create and implement intervention strategies aimed at reducing suicide among Black transgender and nonbinary young people. Additionally, barriers for Black transgender and nonbinary mental health professionals and researchers should be assessed and appropriately addressed. Finally, existing structures of support must necessarily be anti-racist and gender-affirming to truly reach this group of young people.

The Trevor Project remains committed to improving the mental health of Black transgender and nonbinary young people. We have provided resources for people who are invested in finding ways to support Black LGBTQ young people, being an ally to transgender and nonbinary young people, how to approach conversations around the intersection of race and LGBTQ identities, and the magic of Black queerness. Furthermore, our public training team is committed to training professionals and organizations that are in direct contact with Black transgender and nonbinary young people to be more affirming of their identities. We also offer TrevorSpace, our safe space social networking site, as a way for LGBTQ young people to connect with supportive peers, and our advocacy team works to advance trans-inclusive policies. For Black young people who may find themselves in crisis, we have affirming, culturally competent 24/7 crisis services that are available via phone, chat, and text. Finally, our research team will continue to explore and amplify Black transgender and nonbinary experiences in an effort to share ways to support and empower them to reach their full potential.

References

- Bowleg, L., & Bauer, G. (2016). Invited reflection: Quantifying intersectionality. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 337-341.

- Chan, A., Sansfaçon, A. P., & Saewyc, E. (2022). Experiences of discrimination or violence and health outcomes among Black, Indigenous and People of Colour trans and/or nonbinary youth. Journal of Advanced Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15534

- Lesane-Brown, C. L. (2006). A review of race socialization within Black families. Developmental Review, 26(4), 400–426. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.001

- Lindsey, M. A., Sheftall, A. H., Xiao, Y., & Joe, S. (2019). Trends of suicidal behaviors among high school students in the United States: 1991–2017. Pediatrics, 144(5) e20191187. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1187

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C.N., Robin, L., & Underwood, J. M.(2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 States and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 68(3), 67–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

- Jones, S. C., & Neblett, E. W. (2017). Future directions in research on racism-related stress and racial-ethnic protective factors for Black youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(5), 754-766.

- Price-Feeney, M., Green, A. E., & Dorison, S. (2020). All Black lives matter: Mental health of Black LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/All-Black-Lives-Matter-Mental-Health-of-Black-LGBTQ-Youth.pdf

- Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W.. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(5),e1097-e1103. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2712

- Stone D.M, Mack, K.A., Qualters. J.(2023). Notes from the field: Recent changes in suicide rates, by race and ethnicity and age group — United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Report, 72, 160–162. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7206a4.

- Vance, S. R., Boyer, C. B., Glidden, D. V., & Sevelius, J. (2021) Mental health and psychosocial risk and protective factors among Black and Latinx transgender youth compared to peers. JAMA Network Open, 4(3):e213256. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3256

For more information please contact: [email protected].