Background

LGBTQ+ young people are more likely to report mental health concerns – including depression, anxiety, and suicidality – in comparison to their straight and cisgender peers (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020). These reports are often due to minority stress experiences, such as identity-related discrimination and victimization, rather than simply being LGBTQ+ (Meyer, 2003). After a call for intersectional research on health disparities by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, 2015), some research has begun to illuminate the impact of having multiple marginalized identities (e.g., being LGBTQ+ and a person of color) on mental health outcomes (Cyrus, 2017). However, very little research has explored the mental health of Middle Eastern and Northern African (MENA) LGBTQ+ young people (Hayek et al., 2022). Despite representing over 20 countries and being considered non-White by the majority of other Western countries (Maghbouleh et al., 2022), MENA people have historically been considered both a monolithic population in the United States (U.S.) and White by the U.S. Census (Abboud et al., 2019). Thus, little research has explored the mental health of MENA people, as they are often combined with White people in literature. However, a systematic review found that MENA LGBTQ+ people frequently report symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress, suicidal ideation, and substance misuse, which is often tied to societal and cultural stressors that are unique to MENA people, such as a lack of sexual health awareness and anti-LGBTQ+ stigma and persecution (Hayek et al., 2022). Specific to young people, research by GLSEN suggests that MENA LGBTQ+ young people experience higher rates of school-based victimization than their non-MENA peers, which is related to depressive symptoms and poor self-esteem (Truong & Kosciw, 2022). Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ+ Youth Mental Health, this brief will be one of the first to exclusively explore the mental health of MENA LGBTQ+ young people, separately from White LGBTQ+ young people.

Results

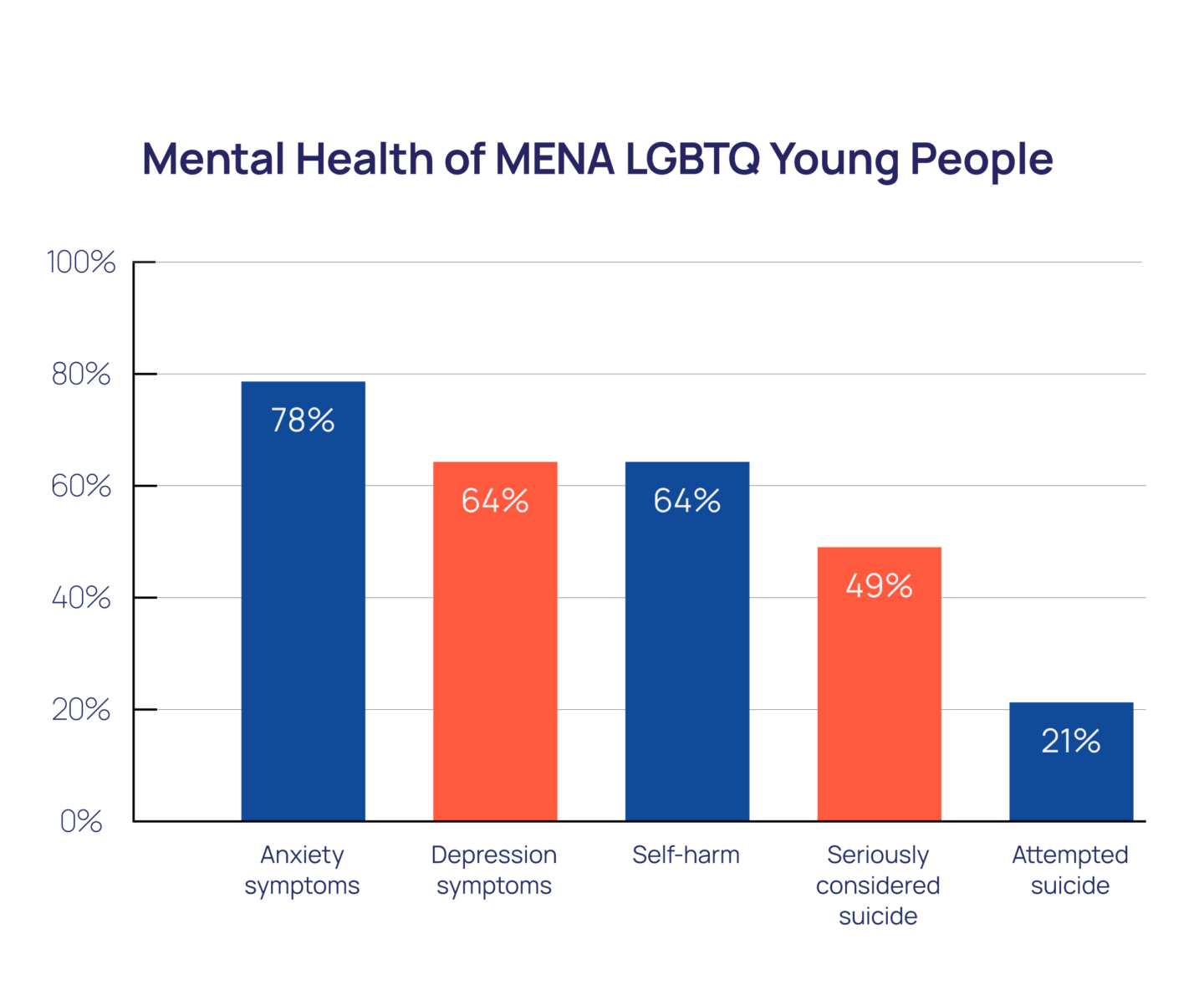

More than one in five (21%) MENA LGBTQ+ young people reported a suicide attempt in the past year. In addition, nearly half (49%) reported seriously considering suicide, and nearly two-thirds (64%) reported engaging in self-harm in the past year. Regarding recent mental health symptoms, 64% reported experiencing depressive symptoms and 78% reported experiencing anxiety symptoms in the past two weeks.

MENA LGBTQ+ young people had greater odds of reporting anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, self-harming behaviors, and suicide attempts in comparison to their non-MENA peers. In particular, when compared to their White peers, MENA LGBTQ+ young people had 65% higher odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR=1.65, p < .001, 95% CI [1.28, 2.13]). MENA and non-MENA LGBTQ+ young people reported similar rates of seriously considering suicide.

Despite reporting high rates of poor mental health, nearly half (46%) of MENA LGBTQ+ young people did not receive wanted mental health care. This rate was similar to their White peers (47%). The top reasons for being unable to access care were not wanting to ask for parental permission (46%), being afraid they would not be taken seriously (45%), and being afraid to talk about their mental health concerns (44%), which are also top reasons for non-MENA LGBTQ+ young people. Specific to their intersectional experience, nearly a third (31%) of MENA LGBTQ+ young people reported that their parent/caregiver would not allow them to go to therapy, in comparison to 19% of their non-MENA peers. Furthermore, nearly one in five (18%) MENA LGBTQ+ young people reported not seeing a mental health provider in the past year because they did not believe the provider would understand their cultural background, in comparison to 6% of their non-MENA peers.

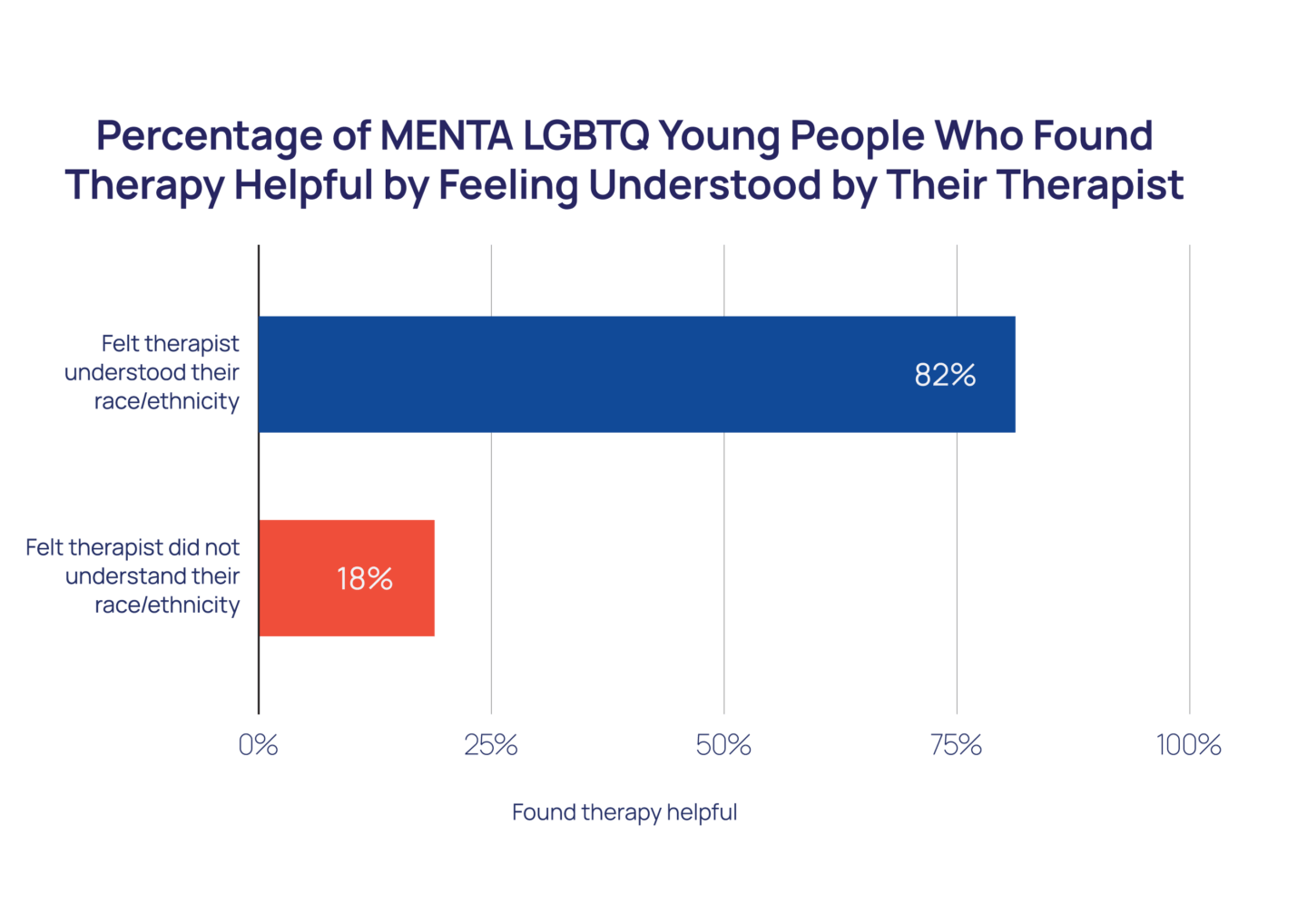

More than four in five (82%) MENA LGBTQ+ young people who felt that their therapist understood their racial/ethnic background found therapy helpful. However, more than one in three (35%) felt that their therapist did not understand their racial/ethnic background. Comparably, when participants did not feel that their therapist understood their racial/ethnic background, only 18% found therapy helpful. Ultimately, MENA LGBTQ+ young people who felt that their therapist understood their racial/ethnic background had more than five times greater odds of finding therapy helpful (aOR=5.40, p<.001, 95% CI [3.09, 9.45]).

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2021 of 33,993 LGBTQ+ young people (ages 13-24) recruited via targeted ads on social media. Participants were asked

“What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with nine options, including: Asian/Asian American; Black/African-American; Hispanic or Latino/Latinx; Indigenous/Native; Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian; Middle Eastern or Northern African; White; More than one race or ethnicity; and, Another race or ethnicity not listed above (please specify). Young people who selected “More than one race or ethnicity” were asked a follow-up question, “With which of the following racial/ethnic groups do you most closely identify? Please select all that apply,” with the same options. Because there were no significant differences in mental health indicators between those who identified as exclusively MENA (n = 238) and multiracial MENA (n = 277), the current analyses include 515 MENA LGBTQ+ young people from both groups. Participants who identified as White were considered White and participants who did not identify as MENA were considered non-MENA (i.e., includes White and non-White participants). Questions assessing past-year suicidality and self-harm were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Questions assessing anxiety and depression were taken from the GAD-2 (Plummer et al., 2016) and PHQ-2 (Richardson et al., 2010), respectively. Participants were asked if they desired and received mental health services, as well as faced barriers when attempting to receive or benefit from services. Chi-square tests were used to examine differences between groups. Adjusted logistic regression models were run to determine the odds of experiencing mental health indicators and finding therapy helpful while controlling for sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual orientation, and Census region. All reported comparisons and adjusted odds ratios are statistically significant at least at p<0.05. This means that there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance.

Looking Ahead

Our findings show that MENA LGBTQ+ young people reported high rates of recent anxiety and depression, as well as self-harm, seriously considering suicide, and attempting suicide in the past year. These rates are often higher than both their non-MENA and, separately, White peers. Additionally, nearly half of MENA LGBTQ+ young people reported not having access to wanted mental health care, with some fearing that a provider would not understand their racial/ethnic background. This fear is well-founded, as more than a third of MENA LGBTQ+ young people who saw a therapist felt that the therapist did not understand their racial/ethnic background, which made therapy less helpful.

Given that MENA people have often been combined with White people in previous literature (Abboud et al., 2019), little is known about their unique health-related experiences (Hayek et al., 2022). Because of the scarcity of research on this group, especially MENA LGBTQ+ young people, future research must intentionally recruit MENA LGBTQ+ young people, consider categorizing MENA people as non-White in analyses in light of potential differences in mental health outcomes and experiences, and report on specific health disparities for this population. Given sample size limitations, this brief was unable to examine within-group differences for MENA people. Thus, future research can also analyze the health outcomes of individuals from specific areas in the MENA region, when sample sizes allow.

For MENA LGBTQ+ young people to access proper care and resources, there must be more MENA representation among mental health care providers. Additionally, culturally-informed training that addresses the specific needs of young people who are at the intersection of being MENA and LGBTQ+ should be given to all mental health care providers. These trainings can include a review of MENA cultural practices, historical events related to the MENA LGBTQ+ community, and affirming language specific to MENA LGBTQ+ young people. Finally, it is essential to advocate for affirming spaces for MENA LGBTQ+ young people by improving current spaces (e.g., more MENA representation in school and community organizations, more MENA-inclusive resources) and creating new spaces (e.g., a Middle Eastern and Northern African club at school).

At The Trevor Project, we are committed to improving the mental health of MENA LGBTQ+ young people. We recognize that all LGBTQ+ young people deserve access to affirming mental health services, with providers who work to understand their background. Trevor’s Crisis Services team is committed to providing empathetic support across our services, with experienced counselors that reflect the diversity of the young people we serve. Additionally, Trevor’s Research team is committed to the ongoing dissemination of data that allow Trevor and others to better address the needs of MENA LGBTQ+ young people.

References

- Abboud, S., Chebli, P., & Rabelais, E. (2019). The contested whiteness of Arab identity in the United States: Implications for health disparities research. American Journal of Public Health, 109(11), 1580–1583. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305285

- Cyrus, K. (2017). Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ+ people of color. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(3), 194–202. DOI: 10.1080/19359705.2017.1320739

- Hayek, S. E., Kassir, G., Cherro, M., Mourad, M., Soueidy, M., Zrour, C., & Khoury, B. (2022). Mental health of LGBTQ+ individuals who are Arab or of an Arab descent: A systematic review. Journal of Homosexuality, 1–23. DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2022.2060624

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., & Underwood, J. M. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 States and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3external

- Maghbouleh, N., Schachter, A., & Flores, R. D. (2022). Middle Eastern and North African Americans may not be perceived, nor perceive themselves, to be White. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(7), e2117940119. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2117940119

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- National Institutes of Health. (2015). NIH FY 2016–2020 strategic plan to advance research on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities. https://www.edi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/EDI_Public_files/sgm-strategic-plan.pdf.

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

- Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1097-e1103. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2009-2712

- Truong, N. L., & Kosciw, J. G. (2022). The experiences of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) LGBTQ+ students in U.S. secondary schools. Research brief. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED623189.pdf.

For more information please contact: [email protected]