Summary

Pride Month is celebrated each June to honor the 1969 Stonewall riots and the efforts of those who have worked to pursue equality for all members of the LGBTQ community (Hegarty & Rutherford, 2019). Pride month highlights opportunities for LGBTQ people to openly express their LGBTQ identity and for allies to have an opportunity to show love and support for LGBTQ people. It is also a time to recognize the resilience of LGBTQ people. Although there is growing research on the role of ethnic identity pride in fostering resilience among youth of color (Rivas‐Drake et al. 2014), less is known about LGBTQ pride, including how it operates across the intersections of sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity. This brief uses data from The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health to examine LGBTQ pride among a diverse sample of nearly 35,000 LGBTQ youth ages 13–24, with attention to intersectional variations in reports of pride as well as how pride is related to suicide risk among LGBTQ youth.

Results

LGBTQ youth who had high levels of LGBTQ pride had nearly 20% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year compared to those with lower levels of LGBTQ pride (aOR=0.81, p<.001). Among transgender and nonbinary youth, this relationship was even stronger, with high levels of pride associated with nearly 30% lower odds of a past-year suicide attempt (aOR=0.71, p<.001).

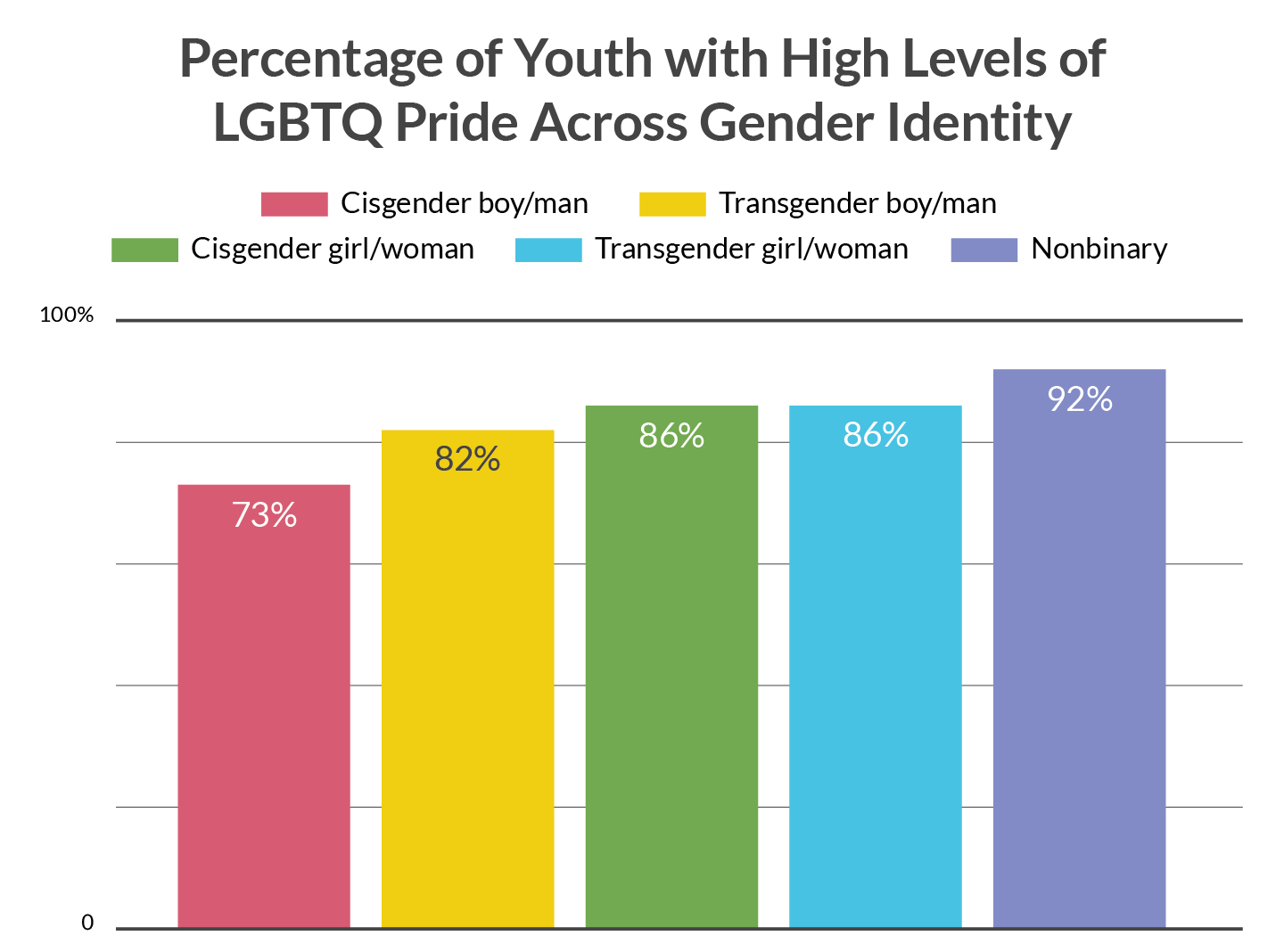

Overall, 85% of LGBTQ youth reported high levels of LGBTQ pride. Nonbinary youth (92%) were the most likely to report high levels of LGBTQ pride, while cisgender boys/men (73%) were the least likely to report high levels of LGBTQ pride. A similar pattern of gender differences in LGBTQ pride was found across all races/ethnicities. Rates of LGBTQ pride were mostly similar across race/ ethnicity, ranging from a low of 84% of Asian/Pacific Islander and Black youth to 89% of Native/Indigenous youth. A greater proportion of LGBTQ youth between the ages of 13–17 (88%) reported high levels of pride compared to those ages 18–24 (82%).

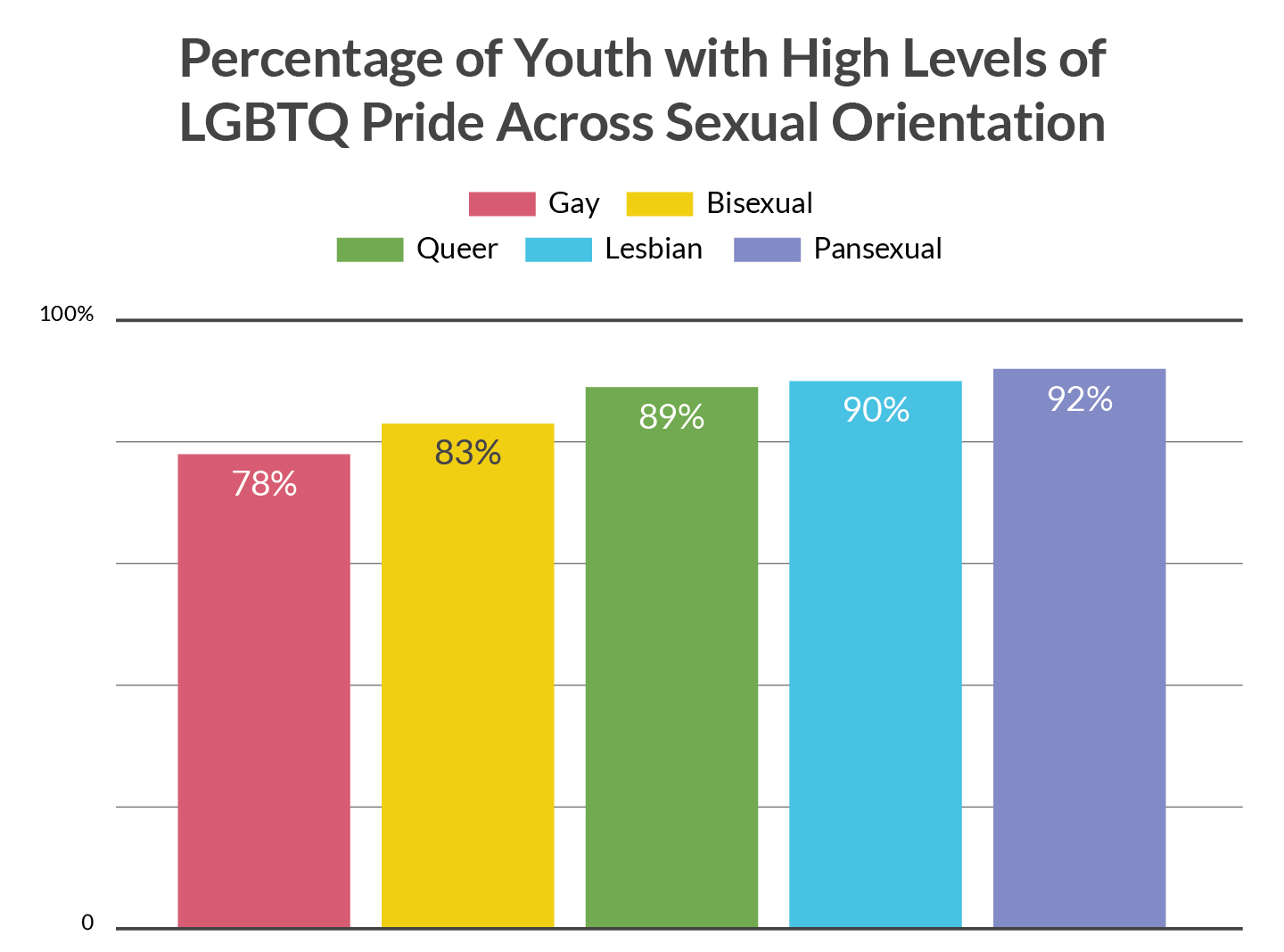

LGBTQ youth who identified as pansexual (92%) were the most likely to report high levels of LGBTQ pride, while those who identified as gay had the lowest levels of LGBTQ pride. Youth who identified as bisexual (83%) were less likely to report high levels of LGBTQ pride than those who identified as pansexual. LGBTQ youth who identified as lesbian (90%) and queer (89%) also had higher levels of LGBTQ pride.

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between October and December 2020 of nearly 35,000 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. LGBTQ pride was measured using the four-item “affective pride” subscale of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Group Identity measure (Sarno & Mohr, 2016), which was adapted to be inclusive of the broader LGBTQ community. Responses were provided on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Scores were dichotomized into youth with an average score above three (high levels of pride) and below three (lower levels of pride). Our question on attempted suicide (“During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”) was taken from the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey. A logistic regression model adjusting for age, gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity, was used to examine the association of high levels of LGBTQ pride with past-year attempted suicide. Exploratory adjusted logistic regression models were also run separately by age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and based on transgender and nonbinary status. To control for random error, only results of logistic regression findings that were significant at p<.001 are presented.

Looking Ahead

Our data suggest that greater levels of pride in the LGBTQ community are associated with lower rates of attempted suicide in the past year among LGBTQ youth. Such findings point to ways the broader community can support LGBTQ youth by widely spreading positive messages about the joys and positive aspects of being LGBTQ. Instilling LGBTQ pride in others is somewhat unique as a protective factor, as it is grounded in positive messaging from the broader community of LGBTQ people and allies rather than relying on changes in the microenvironment where LGBTQ youth live. Although there is a need to continue the ongoing fight for the rights of LGBTQ people, particularly those who have multiple marginalized identities, there is also a need to focus on sources of strength and resilience among LGBTQ youth that may reduce the risk for suicide.

Notably, in our sample, youth who identified as nonbinary and/or pansexual expressed the greatest levels of pride in the LGBTQ community, while those who identified as gay and/or as cisgender men expressed the lowest levels of pride in the LGBTQ community. These findings point towards the need for even greater inclusivity in messaging and portrayals of the LGBTQ community. Individuals who feel the highest levels of pride in being part of the LGBTQ community may also be most impacted by positive portrayals of LGBTQ people like them. In GLAAD’s 2020 Studio Responsibility index, gay men comprised the majority of LGBTQ representation in film (68%), with very little representation of those who were transgender or bisexual (GLAAD, 2020). By expanding LGBTQ representation, individuals who may benefit most may be able to better connect with relevant content. The Trevor Project is committed to fostering resilience and LGBTQ pride among LGBTQ youth. For example, our 24/7 TrevorLifeline, TrevorText, and TrevorChat provide youth with high-quality support and identity affirmation in moments of crisis, while our peer-support network TrevorSpace offers a supportive environment and sense of LGBTQ community for youth around the world. Like our community’s earliest activists, The Trevor Project is proudly here for LGBTQ young people in all the ways they need us. We celebrate the progress that’s been made on their behalf, while also maintaining an energized focus on inclusivity, access, and action in the LGBTQ community.

| ReferencesGLAAD. (2020). Studio Responsibility Index. Available at: https://glaad.org/sri/2020/ Accessed on May 10, 2021.Hegarty, P., & Rutherford, A. (2019). Histories of psychology after Stonewall: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 74(8), 857-867. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000571Rivas‐Drake, D., Seaton, E. K., Markstrom, C., Quintana, S., Syed, M., Lee, R. M., … & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85(1), 40-57.Sarno, E., & Mohr, J. (2016). Adapting the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure to Assess LGB Group Identity. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(3), 293-303. |

For more information please contact: [email protected]