Background

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among youth ages 10-24 in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) 2020 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) indicates that lesbian, gay, and bisexual young people have more than four times increased risk of attempting suicide compared to their heterosexual peers (Johns et al., 2020). There is also a growing body of research illustrating that transgender and nonbinary youth report even higher rates of attempting suicide compared to cisgender youth, including their cisgender lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer/questioning peers (Johns et al., 2010; Price-Feeney, Green, & Dorison, 2020). However, the minority stress model suggests that these disparities between lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth and their heterosexual, cisgender peers are not due to their identity in and of itself, but instead the result of chronic stressors, such as discrimination, victimization, and rejection, stemming from their marginalized social status (Hatzenbuehler & Pachinkis, 2016). The model also highlights the potential for protective factors, such as social support and acceptance, to mitigate these disparities. Indeed, multiple studies find that LGBTQ acceptance from one’s family is associated with better mental health among LGBTQ youth (Bouris et al., 2010; Ryan et al., 2010). Our own research also finds that LGBTQ youth who have LGBTQ-affirming and gender-affirming homes report lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year (The Trevor Project, 2022a). However, much of this work on family acceptance is limited specifically to prenatal and caregiver acceptance. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief seeks to add to the literature by examining the level of support young people receive for their sexual orientation from different members of their family to broaden our understanding of family support as a protective factor for suicide risk.

Results

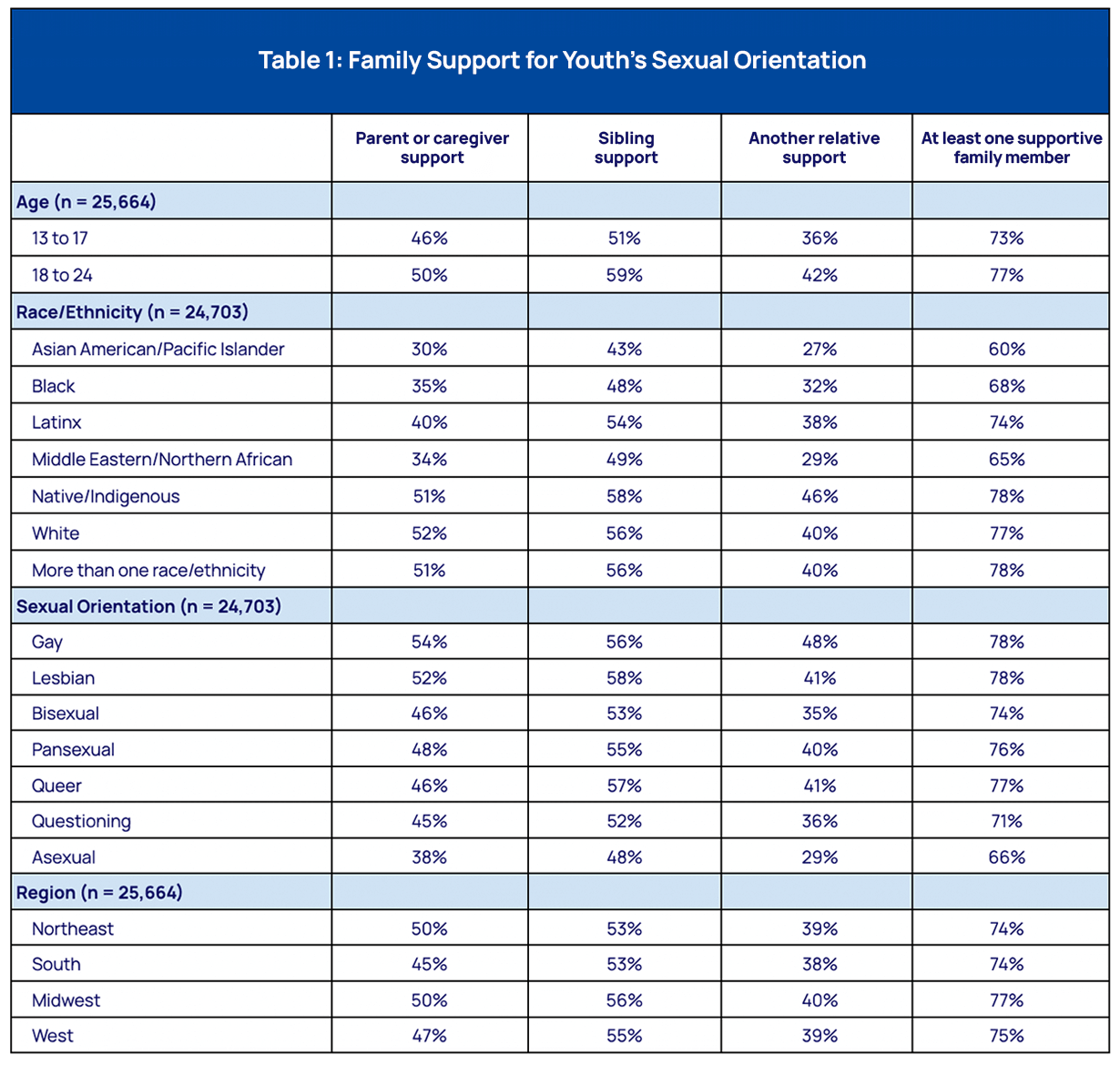

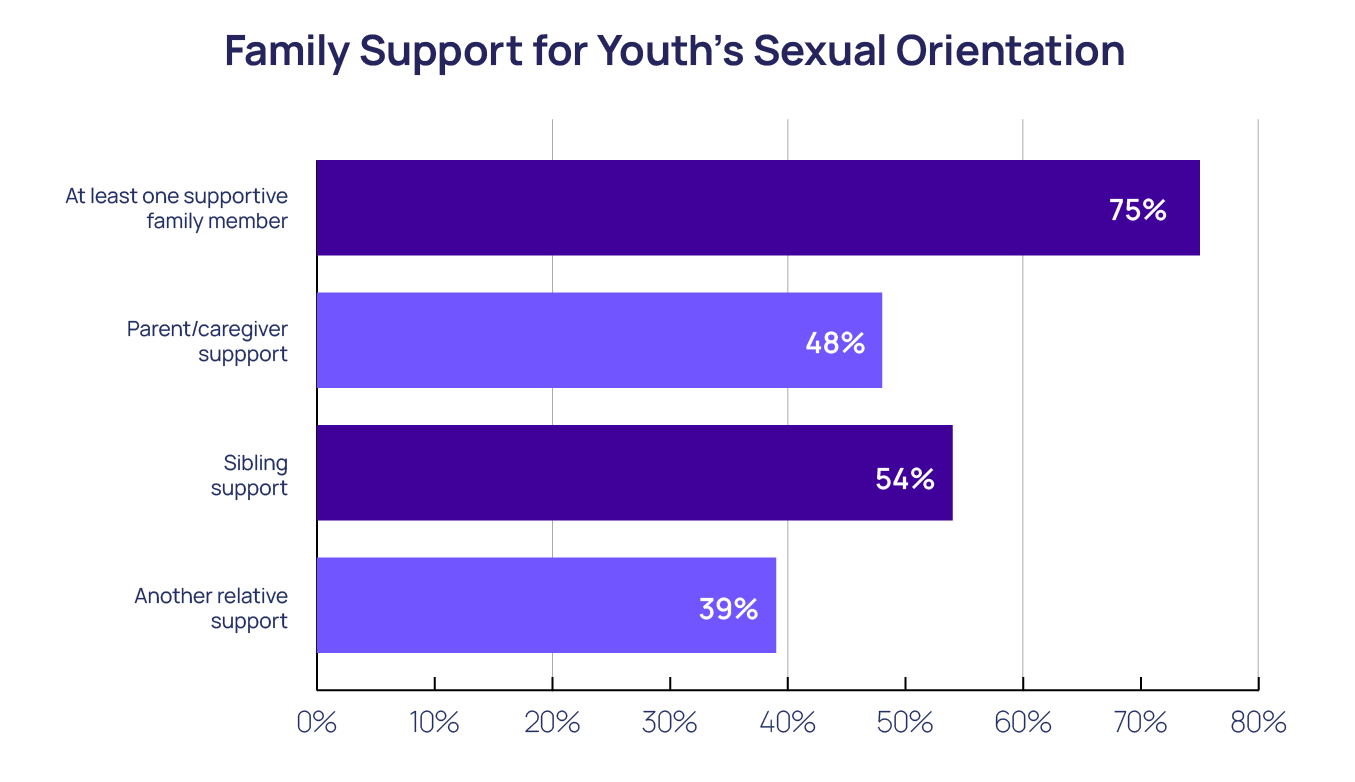

Overall, 3 in 4 LGBTQ youth who were out reported having at least one family member who supports their sexual orientation. Sexual orientation support most frequently came from a sibling (54%), followed by a parent or caregiver (48%), and lastly from another relative (39%). Asexual youth (66%) and youth who were questioning their sexual orientation (71%) had the lowest rates of family support, while youth who were gay (78%) and lesbian (78%) reported the highest rates of having at least one supportive family member. More times than not, having support from a parent/caregiver also corresponded with having support from a sibling (69%) or another relative (55%). However, youth who did not have parental support reported higher rates of sibling support (41%) than support from another relative (24%). That said, it is also important to have a better understanding of how family support for sexual orientation looks for different subgroups of LGBTQ youth based on age, race/ethnicity, and region (see Table on page 5).

Older LGBTQ youth reported higher rates of family support compared to younger LGBTQ youth. LGBTQ youth who were 18-24 years old reported higher rates of having at least one supportive family member (77%) compared to LGBTQ youth who were 13-17 years old (73%). LGBTQ youth ages 18-24 also reported higher rates of each kind of family member support.

Across all race/ethnicity categories, at least 3 in 5 LGBTQ youth reported having support from at least one family member. However, Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI, 60%), Black (68%), and Middle Eastern/Northern African (MENA, 65%) LGBTQ youth reported the lowest rates of family support. A majority of White, Native/Indigenous, and multiracial LGBTQ youth reported having parent/caregiver support, while reported rates of parent/caregiver support among Latinx, Black, MENA, and AAPI youth were lower and more comparable to the rates of support from other family members.

LGBTQ youth in the South had the lowest rates of support from a parent or caregiver compared to other regions in the U.S. Overall, rates of having at least one supportive family member were highest in the Midwest (77%), with other regions reporting comparable rates. However, this is largely in part due to LGBTQ youth in the Midwest reporting higher rates of support from a sibling, as both the rates of parent/caregiver support and support from other relatives are similar to those reported by LGBTQ youth in other regions. Furthermore, while LGBTQ youth in the South report relatively similar rates of having support from a sibling or another relative, the rate of parent/caregiver support was, on average, 10% lower than in other regions.

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2021 of 33,993 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. Youth were asked “Has anyone in your life been supportive of your sexual orientation? Please select all that apply.” There were 17 possible options to choose from, including 1) Yes, a parent or caregiver; 2) Yes, a sibling; and 3) Yes, another relative. Youth who selected at least one of those options were coded as having at least one family member who is supportive of their sexual orientation. Youth who did not select any of them were coded as not having any. All analyses were computed only among youth who were out about their sexual orientation.

Looking Ahead

Our findings suggest that sibling relationships may be an important, though often overlooked, source of support for LGBTQ young people. Unfortunately, our current measure does not account for youth who do not have a sibling, suggesting that the rates may be even higher if analyzed only among those who have at least one sibling. Given our previous findings on the importance of sexual orientation support in reducing suicide risk, the findings point to the importance of including siblings in any effort to increase support and affirmation for LGBTQ youth. It is also important to include parents/caregivers to better understand the protectiveness of having and showing their support for their children (The Trevor Project, 2022b), and because they are quite often the first advocate for their LGBTQ child(ren) to also receive support from other family members. Indeed, parents/caregivers must understand the important role they have in providing a safe and supportive environment within which their child(ren) can thrive.

Our findings also illustrate important differences in family support among LGBTQ youth. Older youth may have more support because their families have had time to come to terms with their sexual orientation, and may see their identity as more stable with age. Conversely, the findings also suggest that younger LGBTQ youth may be more at risk for poor mental health due to a lack of acceptance at a critical time. Similarly, asexual youth’s family members may have a harder time accepting and understanding their sexual orientation as a valid and stable identity. The overarching message to parents and caregivers should be that supporting their child in whatever identity they may hold at whatever age they come out is critical (The Trevor Project, 2022c) because that support is much more important to the well-being of LGBTQ youth than whether or not their sexual orientation label may change.

It is also important to recognize that families may confound gender identity and sexual orientation. Families may be reactive to expansive forms of gender expression, or may not understand the connection between a young person’s transgender identity and their sexual orientation label. We separately assessed gender identity support, and look forward to releasing those findings in the future.

Family members of LGBTQ youth of color may show their support in ways that are not as salient to the overall LGBTQ community, such as the bonds that can stem from shared cultural heritage, unique family customs and traditions, and/or religiosity, and are therefore not recognized in media representations or surveys. Furthermore, LGBTQ youth of color may have parents or caregivers who have concerns about their child facing further discrimination and victimization on top of their racial/ethnic identity, and may feel that withholding support for their sexual orientation is in the best interest of their safety. These findings suggest the need for cultural competency in how we collect these data, and to consider how young people of different backgrounds might interpret the same question. They also emphasize the need for public education efforts for parents and families that address these confounding factors head-on and raise awareness of the concept of intersectionality, as we see youth who hold multiple marginalized identities continue to face unique stressors and challenges.

Finally, our finding that LGBTQ youth in the South report lower sexual orientation support from parents/caregivers may be due to the intrinsic connection between culture and religion, where some denominations may advocate for their members to withhold support for the LGBTQ people in their lives. Given LGBTQ youth in the South also report less access to LGBTQ-affirming spaces, more attention should be given to southern LGBTQ youth’s mental health and well-being, including addressing harmful policies and educating the people in their lives about the basics of sexual orientation.

At The Trevor Project, we are dedicated to improving support for all LGBTQ young people. Our public training team is committed to training professionals and organizations that are in direct contact with LGBTQ youth to be more affirming of their identities. We also offer TrevorSpace, our safe space social networking site, as a way for LGBTQ youth to connect with supportive peers, and our advocacy team works to advance LGBTQ-inclusive policies. For youth who may find themselves in crisis, we offer 24/7 crisis services that are available via phone, chat, and text. Finally, our research team will continue to examine the impact of protective factors, such as family support, in an effort to explore and share ways to support LGBTQ young people and empower them to reach their full potential.

References

- Bouris, A., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Pickard, A., Shiu, C., Loosier, P. S., Dittus, P., Gloppen, K., & Michael Waldmiller, J. (2010). A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(5), 273–309.

- Heron M. (2021). Deaths: Leading causes for 2019. National Vital Statistics Reports, 70( 9).

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L. & Pachankis, J.E. (2016). Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: Research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatric Clinics of North America,63(3), 985–997.

- Johns, M.M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C.N., Robin, L., & Underwood, J. M. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 States and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 68(3), 67–71.

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Haderxhanaj, L.T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69,(Suppl-1), 19–27.

- Price-Feeney M., Green, A.E., & Dorison, S. (2020). Understanding the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), 684–690.

- The Trevor Project (2022a). 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. The Trevor Project

- The Trevor Project (2022b). Behaviors of supportive parents and caregivers for LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

- The Trevor Project (2022c). Age of sexual orientation outness and suicide risk The Trevor Project.

- Ryan, C., Russell, S. T., Huebner, D., Diaz, R., & Sanchez, J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(4), 205–213.

For more information please contact: [email protected]