Background

Resilience is defined as the “process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or even significant sources of stress” (American Psychological Association, 2014, para.4). Many different factors, both personal and environmental, can contribute to an individual’s resilience. While social science research has documented various threats to youth mental health — including risk factors that contribute to minority stress among marginalized individuals — many scholars have also called for research to document sources of resilience that may mitigate those risks (Meyer, 2003; Rennie & Dolan, 2010). There is lively debate among health researchers about how to best conceptualize and measure resilience (Colpitts & Gahagan, 2016). Other scholars have critiqued this complex concept, noting that marginalized youth should not be forced to develop resilience in order to survive and thrive in an unaccepting society. Rather, scholars, practitioners, and activists should focus on changing the systems and societal norms which contribute to youths’ marginalization (Anderson, 2019). Nonetheless, there is a growing body of scholarship which explores resilience among LGBTQ youth. Previous scholarship has found that LGBTQ youth described their resilience as “doing well while still in pain,” highlighting the fact that resilience helped them navigate ongoing challenges and stressors (Asakura, 2019). LGBTQ identity can be a form of resilience in and of itself, acting as a source of strength, social connection, and personal growth (Schmitz & Tyler, 2019). While resilience has many components, the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) is designed to measure an individual’s ability to “bounce back” from challenging situations or experiences (Smith et al., 2008). Previous research that tested the BRS among a sample of young adults found that higher BRS scores are associated with lower rates of anxiety and depression (Smith et al., 2008). Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief examines differences in resiliency among LGBTQ youth, and the association of resilience with mental health symptoms and suicide risk.

Results

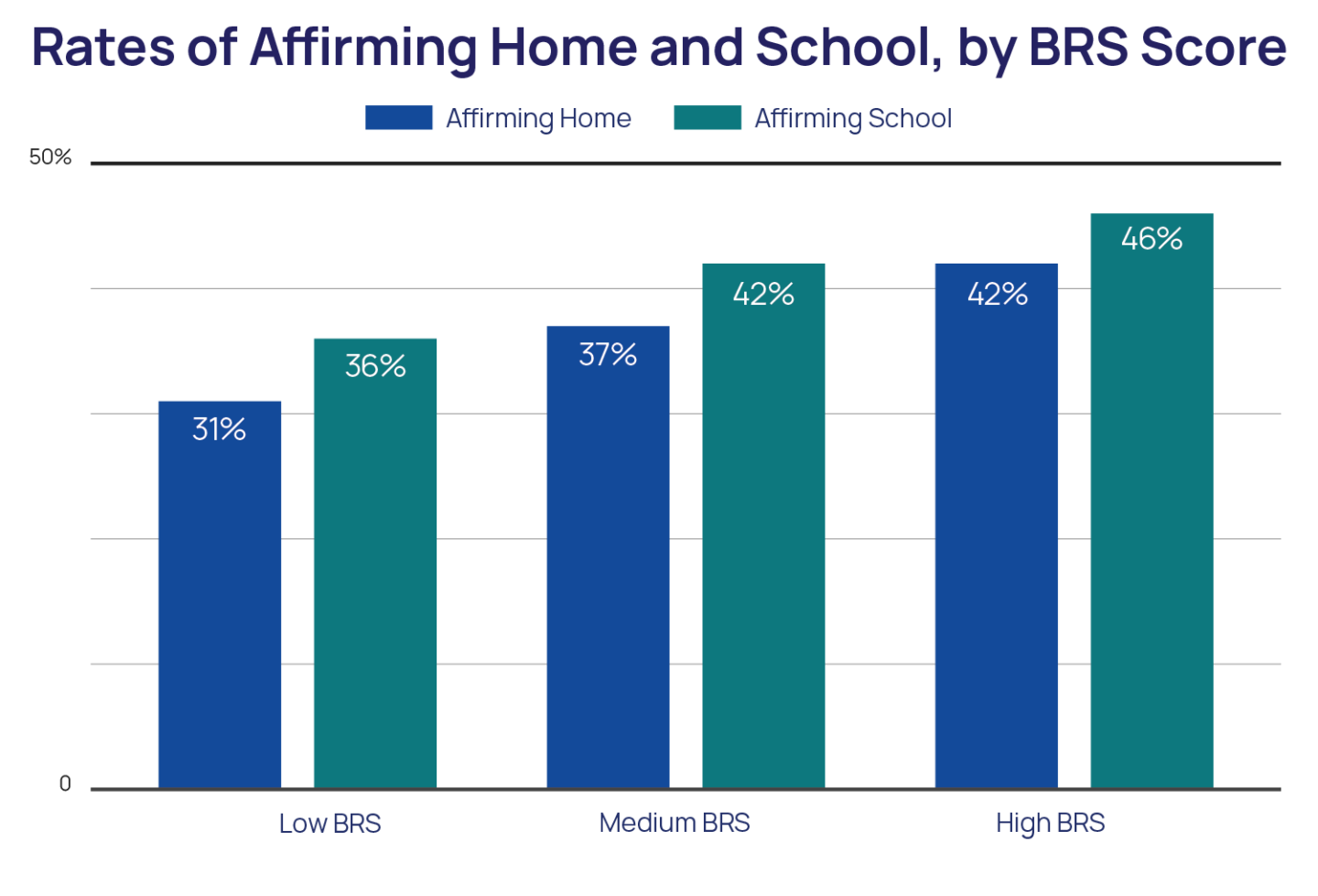

LGBTQ youth who have supportive families and are in supportive environments have higher resilience. LGBTQ youth ages 18 to 24 reported significantly higher resilience than LGBTQ youth ages 13 to 17. LGBTQ youth who reported struggling to meet their basic economic needs reported lower resilience than their peers who could meet their basic economic needs. Compared to gay or lesbian youth, youth who identified their sexual identity as queer, pansexual, asexual, and questioning reported lower resilience. Cisgender boys and men reported the highest resilience and transgender, nonbinary, and questioning youth who had been assigned female at birth reported the lowest resilience, compared to youth of all other gender identities. There were no differences in resilience among LGBTQ youth of different racial or ethnic groups. LGBTQ youth who reported high levels of family support had higher resilience than their peers with low levels of family support. Both LGBTQ youth who reported living in an affirming home or attending an affirming school also reported higher resilience than LGBTQ youth in non-affirming homes or schools.

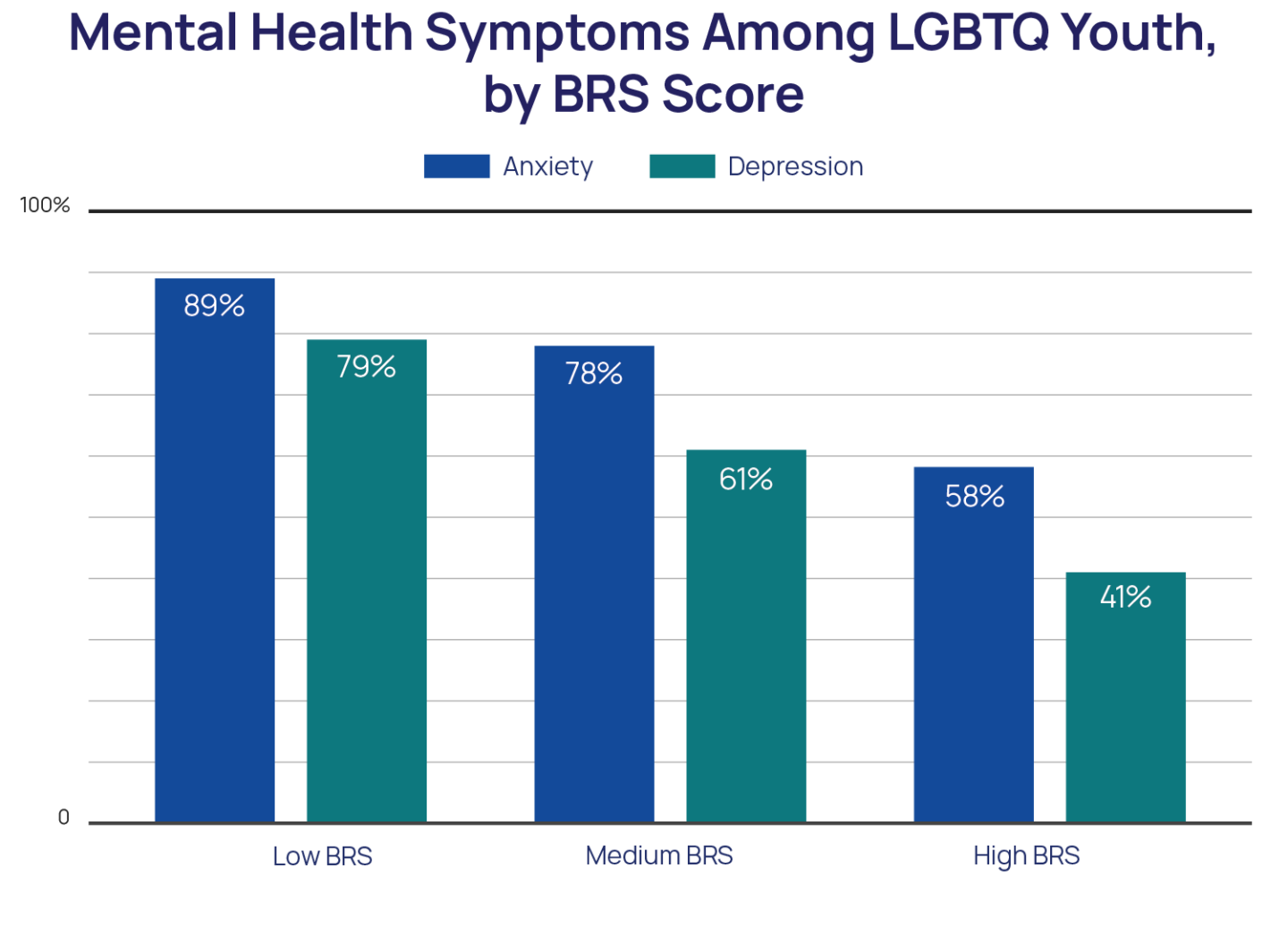

Higher resilience was significantly associated with decreased risk for depression and anxiety among LGBTQ youth. LGBTQ youth with high resilience reported 81% lower odds (aOR = 0.19) of anxiety symptoms, compared to LGBTQ youth with low resilience. 58% of LGBTQ youth with high resilience reported symptoms of recent anxiety, compared to 89% of LGBTQ youth with low resilience. LGBTQ youth with high resilience reported 79% lower odds (aOR = 0.21) of recent depression, compared to LGBTQ youth with low resilience. 41% of LGBTQ youth with high resilience reported symptoms of recent depression, compared to 79% of LGBTQ youth with low resilience.

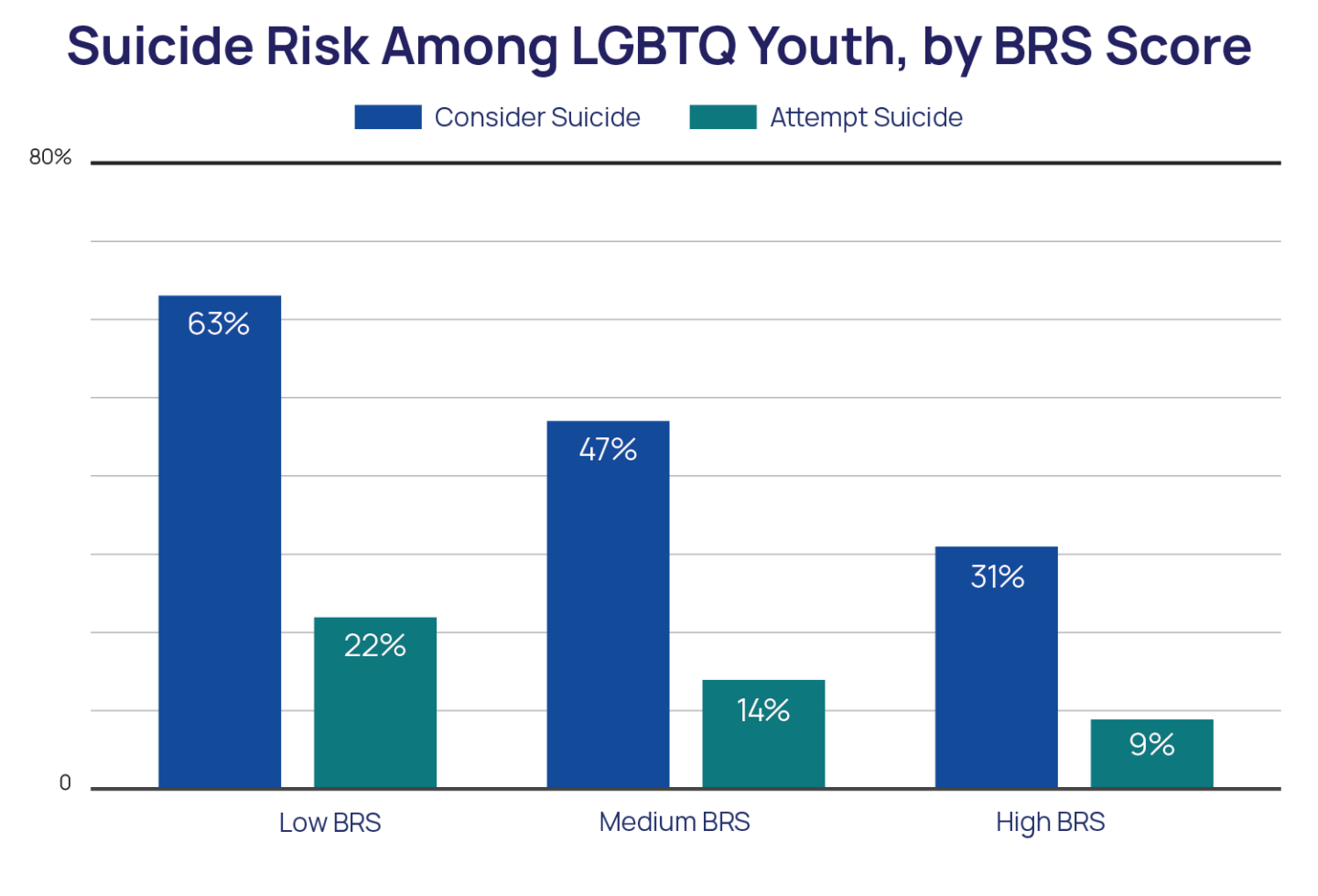

LGBTQ youth with high resilience had 59% lower odds (aOR = 0.41) of reporting a suicide attempt in the past year compared to LGBTQ youth with low resilience. 9% of LGBTQ youth with high resilience reported a suicide attempt in the past year, compared to 22% of LGBTQ youth with low resilience. LGBTQ youth with high resilience reported 69% lower odds (aOR = 0.31) of considering suicide in the past year, compared to LGBTQ youth with low resilience. 31% of LGBTQ youth with high resilience reported seriously considering suicide in the past year, compared to 63% of LGBTQ youth with low resilience.

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2021 of 33,993 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. Resilience was measured using an adapted version of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS), which seeks to measure an individual’s ability to “bounce back” from challenging circumstances. The BRS consists of 6 items: 1) I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times, 2) I have a hard time making it through stressful events, 3) It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event, 4) It is hard for me to snap back when something bad happens, 5) I usually come through difficult times with little trouble, and 6)I tend to take a long time to get over setbacks in my life. Response options included Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, and Strongly Agree. After reverse coding items 2, 4, and 6, mean BRS scores were calculated. T-tests of independence and one-way ANOVAs were used to compare BRS scores across socio-demographics. For some analyses, three groups were created to compare BRS scores. Groups were created to be approximately evenly distributed while accounting for values created after calculated mean BRS: 25% of the sample was in the Low BRS group with scores between 1 and 1.83, 34% was in the Medium BRS group with scores between 2 and 2.33, and 40% was in the High BRS group with scores between 2.17 and 4. Recent anxiety was measured using the GAD-2 and recent depression was measured using the PHQ-2 (Plummer et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2010). The questions assessing past-year suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Adjusted logistic regression models controlled for race/ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual identity, socioeconomic status, family support of LGBTQ identity, affirming home, and affirming school.

Looking Ahead

These findings highlight the association between personal resilience — specifically an individual’s capacity to bounce back from adversity — and mental health among LGBTQ youth. Higher resilience in our sample was consistently associated with better mental health outcomes. Youth with medium or high resilience reported lower odds of both recent anxiety symptoms and recent depression symptoms, as well as suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in the past year, compared to youth with low resilience. These findings highlight the important role that personal resilience may play in mental health among LGBTQ youth, and align with other research documenting similar relationships between resilience and decreased anxiety and depression (Smith et al., 2008).

Given that youth in supportive homes and schools reported higher resilience in our sample, affirmation of one’s LGBTQ identity may contribute to increased feelings of personal resilience. Furthermore, older LGBTQ youth in our sample reported more resilience than younger LGBTQ youth; this may be due to older youth having more time and life experience to develop resilience and effective coping mechanisms. Youth who reported being able to meet or more than meet their basic economic needs also reported more resilience compared to their LGBTQ peers who struggled to meet their basic economic needs; this may be indicative of these youths’ increased access to economic resources to help them deal with adversity and stress. High levels of family support, living in an affirming home, or attending an affirming school were all associated with higher resilience, suggesting the importance that support from family, peers, and other adults has in increasing and developing resilience among LGBTQ youth. There may also be therapeutic interventions that can help LGBTQ youth build increased capacity to bounce back from hard experiences when these affirming environments are not available for them. Additional research and action are needed to better understand and change societal systems which marginalize LGBTQ individuals, including anti-LGBTQ bias, racism, sexism, ableism, and classism. While resilience is an important skill, LGBTQ youth deserve opportunities to thrive and excel, not to just learn the skills necessary to survive while under attack.

The Trevor Project is dedicated to supporting a world where LGBTQ youth can thrive. Our 24/7 crisis services are available in three different modalities — phone, chat, and text — so that youth in crisis have multiple avenues to communicate with culturally competent and affirming counselors. Our public education team offers training on LGBTQ allyship and suicide prevention to a variety of youth-facing organizations. Trevor’s advocacy team works with partners across the United States to protect LGBTQ youths’ rights and provide increased access to suicide prevention resources and our TrevorSpace platform connects youth with supportive peers. Further, Trevor’s research team uses data and scientific insight to advance the scholarly literature on LGBTQ youth mental health. All of these efforts work together to create a world for LGBTQ youth in which resilience is not a requirement for survival.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2014). The road to resilience. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx.

- Anderson, L. A. (2019). Rethinking resilience theory in African American families: Fostering positive adaptations and transformative social justice. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 11(3), 385–397.

- Asakura, K. (2019). Extraordinary acts to “show up”: Conceptualizing resilience of LGBTQ youth. Youth & Society, 51(2), 268–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X16671430

- Colpitts, E., & Gahagan, J. (2016). The utility of resilience as a conceptual framework for understanding and measuring LGBTQ health. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0349-1

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-\–697.

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31.

- Rennie, C. E., & Dolan, M. C. (2010). The significance of protective factors in the assessment of risk. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 20(1), 8–22.

- Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1097–e1103. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2712

- Schmitz, R. M., & Tyler, K. A. (2019). ‘Life has actually become more clear’: An examination of resilience among LGBTQ young adults. Sexualities, 22(4), 710–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460718770451

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

For more information, please contact: [email protected]