Background

LGBTQ young people report significantly higher rates of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors compared to their straight and cisgender peers, including non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts (Johns et al., 2019). Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), henceforth referred to as self-injury, is defined as the purposeful damage of one’s own body without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially or culturally sanctioned (Klonsky et al., 2014). Examples of non-suicidal self-injury can include cutting, scraping, or bruising one’s own body. Self-injury is often motivated by intrapersonal (related to one’s self or own internal state) or interpersonal (related to one’s relationships with others) reasons (International Society for the Study of Self-Injury, 2022). Research suggests that, in the general population, intrapersonal reasons for self-injury may be more prevalent and predictive of future self-injury and suicide attempts than interpersonal reasons (Taylor et al., 2018). However, less is known about the relationship between motivation for self-injury and suicide attempts among LGBTQ young people specifically. Thus, better understanding the prevalence of and motivations behind self-injury in LGBTQ young people could help reduce their heightened rates of self-injury and suicide attempts. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People, this brief adds to the existing literature by examining rates of and motivations for self-injury, as well as the relationship between self-injury and seriously considering or attempting suicide in the past year among a diverse sample of LGBTQ young people.

Results

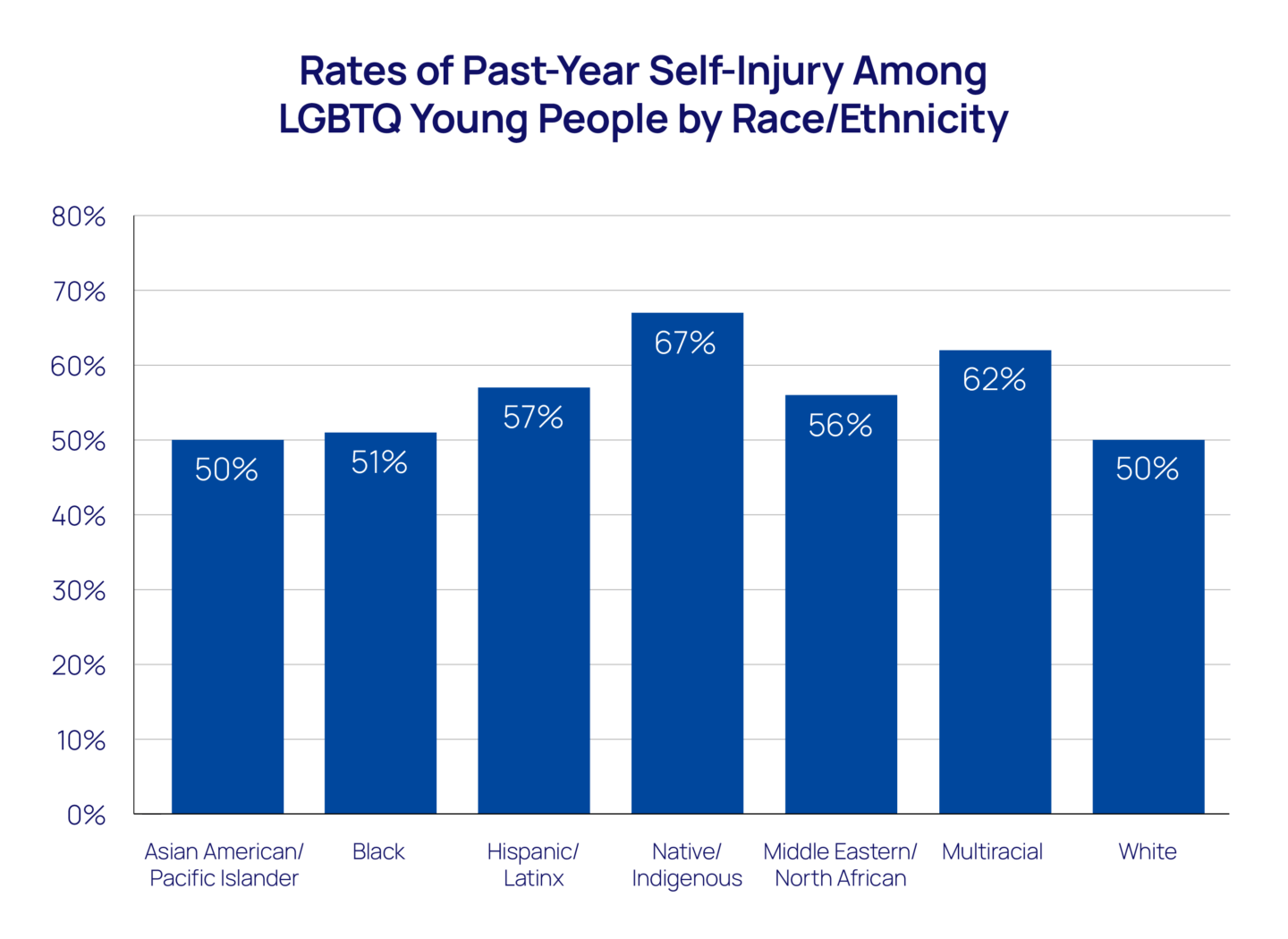

Rates of past-year self-injury were highest among LGBTQ young people ages 13-17, LGBTQ young people of color, and transgender and nonbinary young people. Among the entire sample, 54% reported self-injuring in the past year. LGBTQ young people ages 13-17 reported significantly higher rates of self-injury in the past year (63%) compared to their peers ages 18-24 (41%). Transgender and nonbinary young people reported higher rates of past-year self-injury than their cisgender peers, with transgender boys and men (72%) reporting the highest, followed by nonbinary young people assigned female at birth (68%), transgender girls and women (52%), and nonbinary young people assigned male at birth (48%). Cisgender girls and women (47%) reported higher rates than cisgender boys and men (28%). LGBTQ young people of color reported higher rates than their White LGBTQ peers. Native and Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported the highest rates (67%) of past-year self-injury, followed by Multiracial (62%), Latinx (57%), Middle Eastern and Northern African (56%), Black (51%), Asian American and Pacific Islander (50%), and White young people (50%).

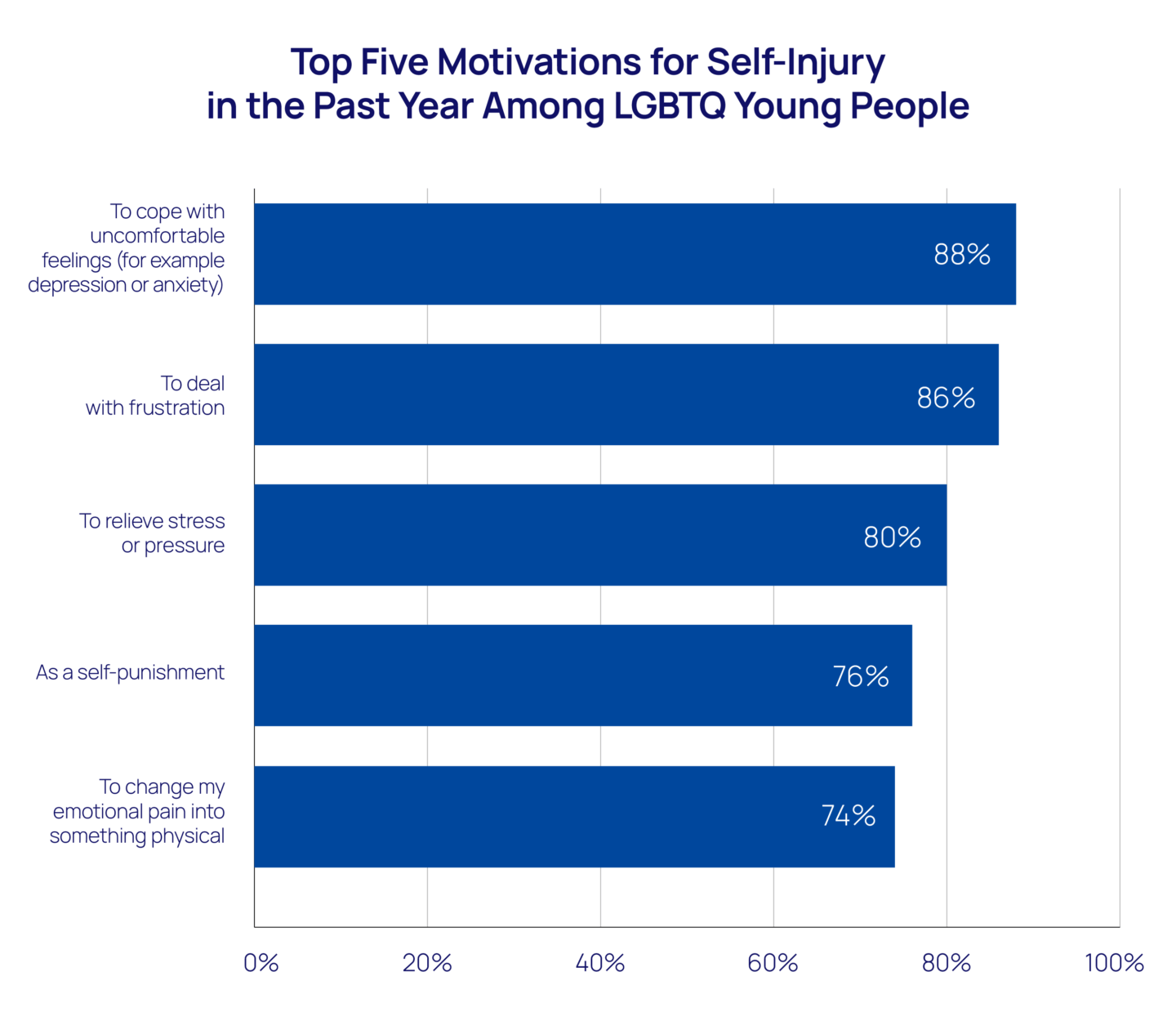

LGBTQ young people reported more frequently engaging in self-injury for intrapersonal reasons than interpersonal reasons. Among the 20 assessed motivations for self-injury, LGBTQ young people who self-injured in the past year endorsed the following top five reasons: to cope with uncomfortable feelings (for example, depression or anxiety; 88%); to deal with frustration (86%); to relieve stress or pressure (80%); as a self-punishment (76%); and, to change my emotional pain into something physical (74%). Furthermore, LGBTQ young people who self-injured in the past year reported significantly higher rates of self-injuring for at least one intrapersonal motivation (99.5%) compared to at least one interpersonal motivation (55%). Just over a quarter of respondents (28%) reported both at least one intrapersonal motivation (e.g., “to feel something”) and at least one interpersonal motivation (e.g., “because my friends injure themselves”) for self-injuring.

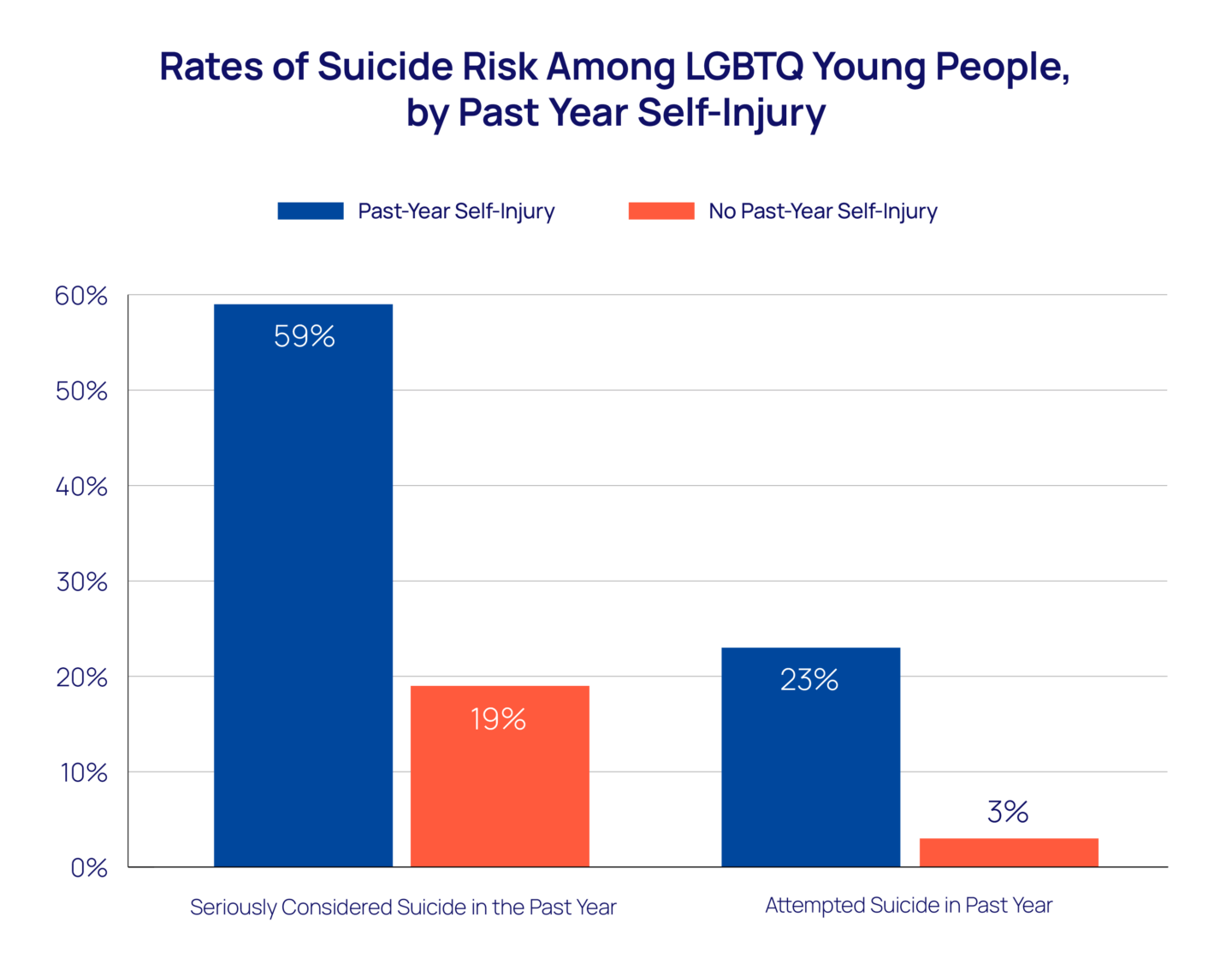

LGBTQ young people who self-injured in the past year reported higher odds of both considering and attempting suicide in the past year compared to LGBTQ young people who did not. Among LGBTQ young people who self-injured in the past year, 59% reported seriously considering suicide in the past year and 23% reported attempting suicide in the past year, which was higher than LGBTQ young people who did not self-injure in the past year (19% and 3%, respectively). Additionally, LGBTQ young people who self-injured in the past year had five times greater odds of seriously considering suicide in the past year (aOR = 5.23, 95% CI [4.91, 5.57], p < 0.001) and nine times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 8.56, 95% CI [7.54, 9.73], p < 0.001).

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2022 of 28,524 LGBTQ young people recruited via targeted ads on social media. The item assessing past-year self-injury was taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020), and asked respondents, “During the past 12 months, how many times did you do something to purposely hurt yourself without wanting to die, such as cutting or burning yourself on purpose?” Response options included: 1) 0 times; 2) 1 time; 3) 2 or 3 times; 4) 4 or 5 times; and, 5) 6 or more times. Young people who had not self-injured in the past year were coded as 0) No, and those who had self-injured at any frequency in the past year were coded as 1) Yes. Young people’s motivations for self-injury were assessed using an adaption of the Non-Suicidal Self-Injury–Assessment Tool (NSSI-AT; Whitlock et al., 2014), which asked participants to “Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements about why you hurt yourself on purpose.” The question included 20 items assessing motivation for self-injury, with the following response options for each item: strongly disagree; disagree; agree; and, strongly agree. Participants who responded either “agree” or “strongly agree” to at least one of the intrapersonal items were grouped together, and participants who responded either “agree” or “strongly agree” to at least one of the interpersonal items were grouped together. Seriously considering or attempting suicide in the past year were assessed using questions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Respondents were asked, “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” with response options 1) No and 2) Yes and, “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” with response options 1) 0 times, 2) 1 time, 3) 2 or 3 times, 4) 4 or 5 times and 5) 6 or more times. Young people who had not attempted suicide in the past year were coded as 0) No, and those who had attempted at any frequency in the past year were coded as 1) Yes. Crosstabs and chi-square analyses were used to examine frequencies and differences in rates among groups. Adjusted logistic regression models were conducted to determine the associations between past-year self-injury and seriously considering or attempting suicide in the past year and while controlling for age, census region, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual identity. All reported comparisons and adjusted odds ratios are statistically significant at least at p < 0.05. This means that there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance.

Looking Ahead

Given the high rates of both self-injury and suicide risk among LGBTQ young people, it is essential to better understand who may be at a greater risk of self-injury, motivations for self-injury, and its relationship to suicide risk among LGBTQ young people. In our sample, rates of past-year self-injury were highest among LGBTQ young people ages 13-17, LGBTQ young people of color, and transgender and nonbinary young people, compared to their peers who were ages 18-24, White, and cisgender, respectively. Our findings also align with existing research on the high prevalence of intrapersonal motivations for self-injury. Of those who had self-injured in the past year, 99.5% of the LGBTQ young people in our sample endorsed at least one intrapersonal reason for self-injuring, compared to 55% who endorsed at least one interpersonal reason for self-injuring. While this may indicate that intrapersonal motivations for self-injury are more common among LGBTQ young people, it may also be impacted by the fact that there were more intrapersonal motivations than interpersonal motivations for respondents to choose from. Furthermore, those who self-injured in the past year had five times greater odds of seriously considering suicide in the past year and nine times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year, highlighting the strong association between self-injury and suicide risk among LGBTQ young people.

These findings illustrate the importance of providing support for LGBTQ young people who self-injure that is both culturally competent and considerate of the underlying motivations behind their self-injury. Notably, holding multiple marginalized identities may compound minority stress among LGBTQ young people and contribute to increased risk of self-injury and suicide attempts (Cyrus, 2017; Meyer, 2003). Given self-injury’s strong associations with suicide risk among LGBTQ young people, it is also important to ensure that LGBTQ young people who self-injure have access to affirming and supportive mental health services. Healthcare professionals working with LGBTQ young people who self-injure should be considerate of the ways young people’s intersecting identities may impact their risk of and motivations for self-injury. Given that supportive parents/caregivers, adult family members, educators, healthcare professionals, and other adults play a crucial role in the mental health of LGBTQ young people (The Trevor Project, 2022), adults with LGBTQ young people in their lives who self-injure should be mindful that they are often self-injuring for reasons related to themselves rather than others. These adults should also be prepared to have open conversations with LGBTQ young people to better understand their personal motivations for self-injury and engage in behaviors that affirm the young person’s LGBTQ identity to help mitigate this risk. Finally, adults working with LGBTQ young people who self-injure should also be educated in harm-reduction approaches (i.e., behaviors designed to limit self-injury and its consequences), which may, in turn, reduce future suicide attempts in LGBTQ young people.

The Trevor Project is committed to supporting all LGBTQ young people who self-injure. Our 24/7 crisis services are available in three different modalities – phone, chat, and text – for young people to connect with affirming counselors who are trained to work collaboratively with LGBTQ young people and use a harm-reduction approach to self-injury. Our Resource Center offers insights on and safe alternatives to self-injury, such as our page on Support for Self-Harm Recovery. Our TrevorSpace platform also connects young people with supportive peers online. Finally, Trevor’s research, advocacy, and public training teams are dedicated to using data, policies, and education to enhance the understanding of the unique motivations behind self-injury among LGBTQ young people, as well as help prevent self-injury whenever possible.

References

- Cyrus, K. (2017). Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(3), 194-202.

- International Society for the Study of Self-Injury. (2022). Why do people self-injure? https://www.itriples.org/

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Underwood, J. M.(2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students — 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., & Suarez, N. A. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

- Klonsky, E. D., Victor, S. E., & Saffer, B. Y. (2014). Nonsuicidal self-injury: What we know, and what we need to know. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(11), 565–568. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F070674371405901101

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Taylor, P. J., Jomar, K., Dhingra, K., Forrester, R., Shahmalak, U., & Dickson, J. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.073

- The Trevor Project. (2022). Behaviors of supportive parents and caregivers for LGBTQ youth. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/behaviors-of-supportive-parents-and-caregivers-for-lgbtq-youth-may-2022/

- Whitlock, J., Exner-Cortens, D., & Purington, A. (2014). Assessment of nonsuicidal self-injury: Development and initial validation of the Non-Suicidal Self-Injury–Assessment Tool (NSSI-AT). Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 935–946. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036611

The authors of this brief acknowledge and extend our deepest thank you to Hannah R. Rosen for its initial draft.

Recommended Citation: The Trevor Project. (2023). Self-Injury and its relationship to suicide attempts among LGBTQ young people.

For more information please contact: [email protected]