Background

For many lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people, going to college or university is an opportunity to connect with other LGBTQ people. However, if campuses do not meet the unique needs of LGBTQ students, such as community support and affirming care, the college environment may also present challenges. Minority stress theory proposes that stress related to having a marginalized social identity, such as being LGBTQ, can contribute to a number of adverse mental and physical health outcomes, including increased suicide risk (Meyer, 2003). As such, barriers faced by LGBTQ young people in college environments may contribute to minority stress and increase their risk of suicide compared to their straight, cisgender peers. Additionally, LGBTQ college students have more negative perceptions of campus climate compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Rankin et al., 2010). LGBTQ college students report high rates of a number of negative experiences and mental health outcomes, including victimization, discrimination, depression, and suicide risk (Woodford et al., 2018). Despite this, protective factors, such as supportive faculty members (Linley et al., 2016) and affirming school policies and spaces (Pitcher et al., 2018), can help mitigate disparities. However, LGBTQ college students often report high rates of unmet needs and barriers to using on-campus mental health services (Dunbar et al., 2017), and limited access to LGBTQ-specific services (Nguyen et al., 2018). Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief adds to the existing literature by examining suicide risk, access to mental health services, and access to LGBTQ services among a national sample of LGBTQ young people enrolled in a college or university, henceforth referred to as college students.

Results

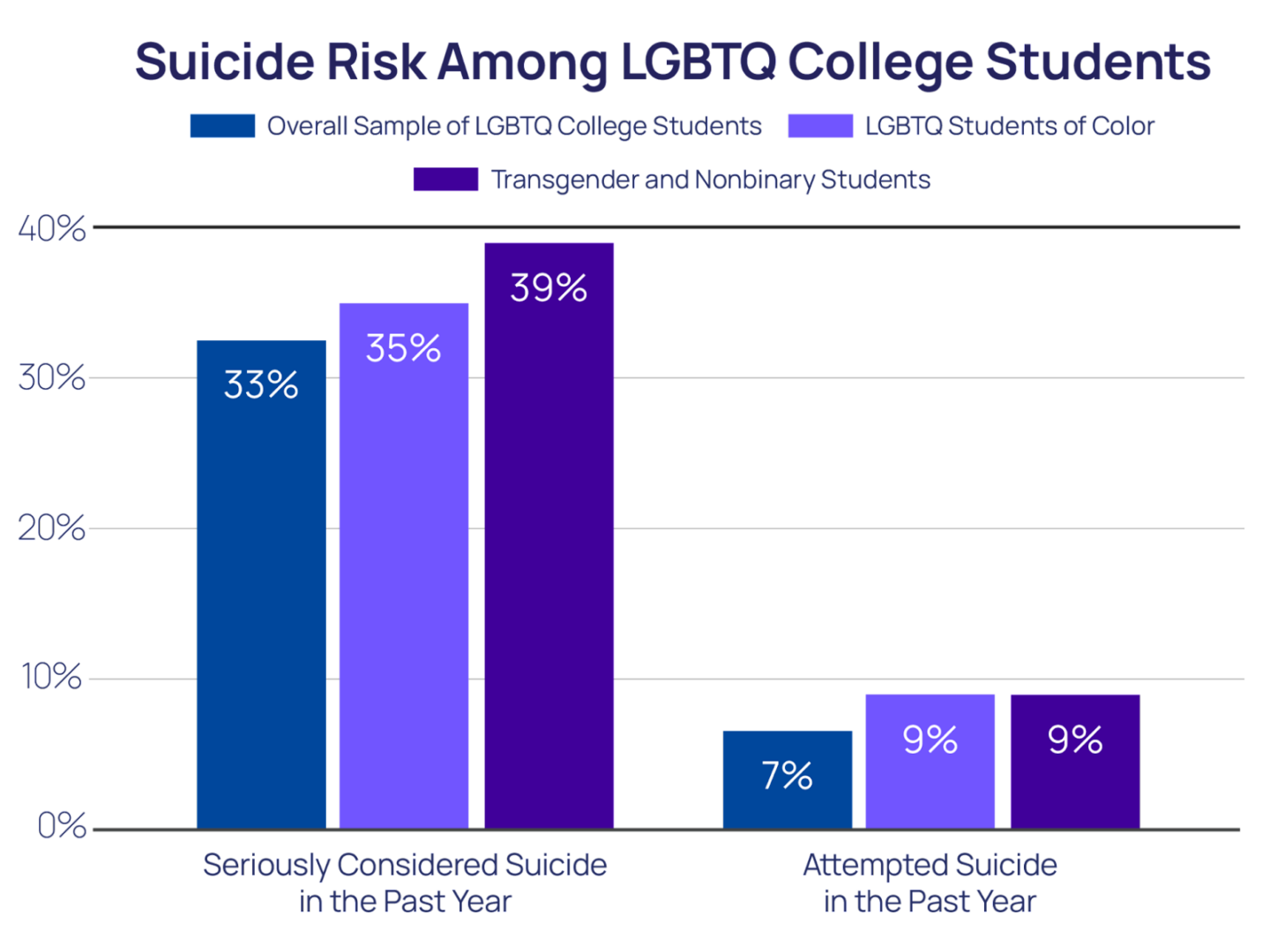

Overall, one in three (33%) LGBTQ college students seriously considered suicide in the past year, and 7% reported a suicide attempt in the past year. Rates of considering suicide were higher among LGBTQ college students of color (35%), multisexual students (35%), and transgender and nonbinary students (39%), compared to White LGBTQ students (31%), monosexual students (29%), and cisgender LGBQ students (26%), respectively. Furthermore, LGBTQ students of color (9%) and transgender and nonbinary students (9%) reported significantly higher rates of attempting suicide in the past year compared to White LGBTQ students (6%) and cisgender LGBQ students (4%), respectively.

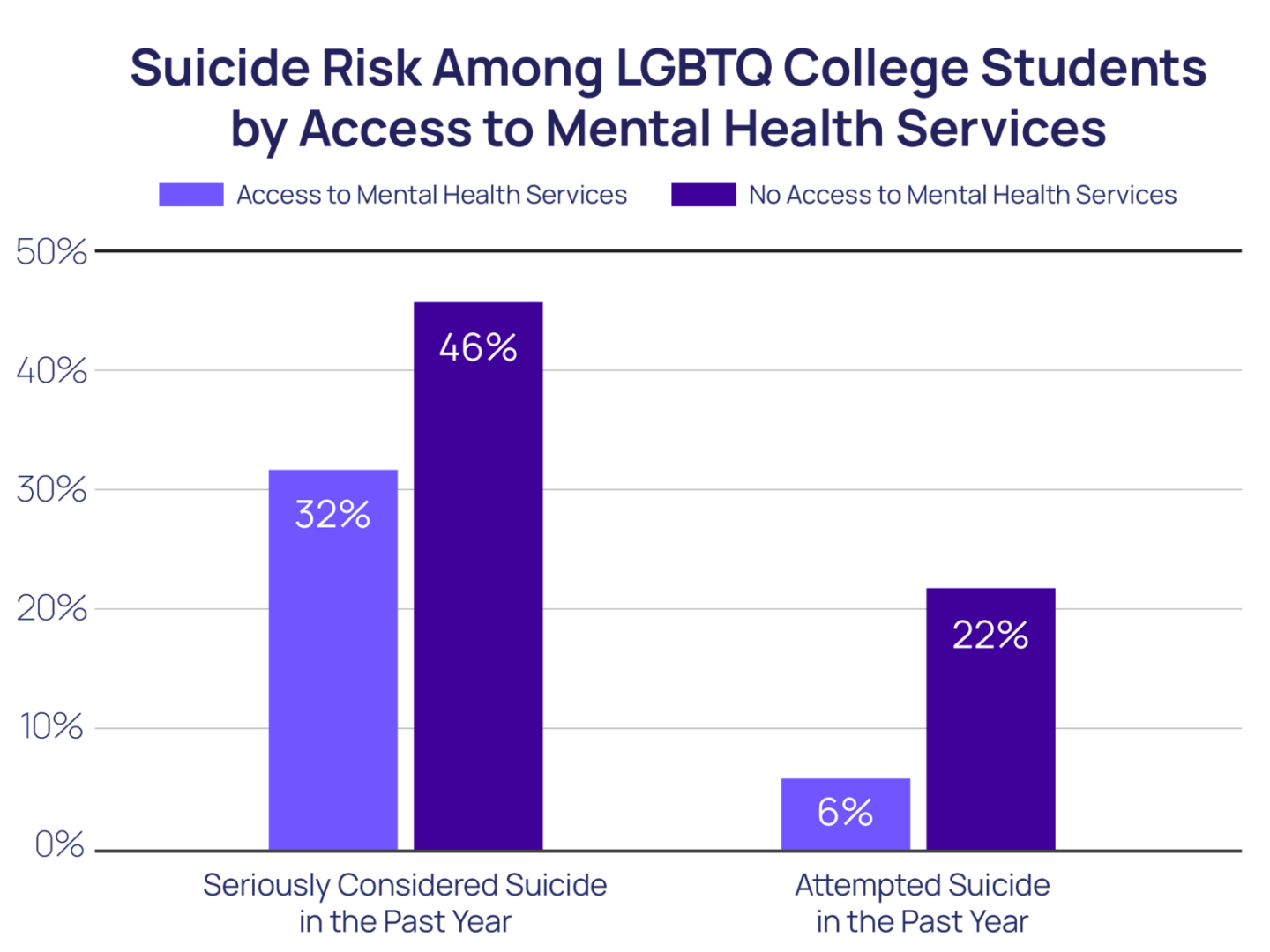

LGBTQ college students with access to mental health services through their college had 84% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 0.16) compared to LGBTQ college students without access. The majority of LGBTQ college students (86%) reported that their college offered mental health services to students; however, LGBTQ college students reported that common barriers to accessing care included that they did not feel comfortable going (33%), long waitlists, (29%), and privacy concerns (17%). Compared to LGBTQ college students who reported that they had access to mental health services through their college (46%), those who did not have access to mental health services through their college reported significantly higher rates of seriously considering suicide in the past year (54%). Similarly, LGBTQ college students who did not have access to mental health services through their college (22%) reported significantly higher rates of attempting suicide in the past year compared to those who had access (6%).

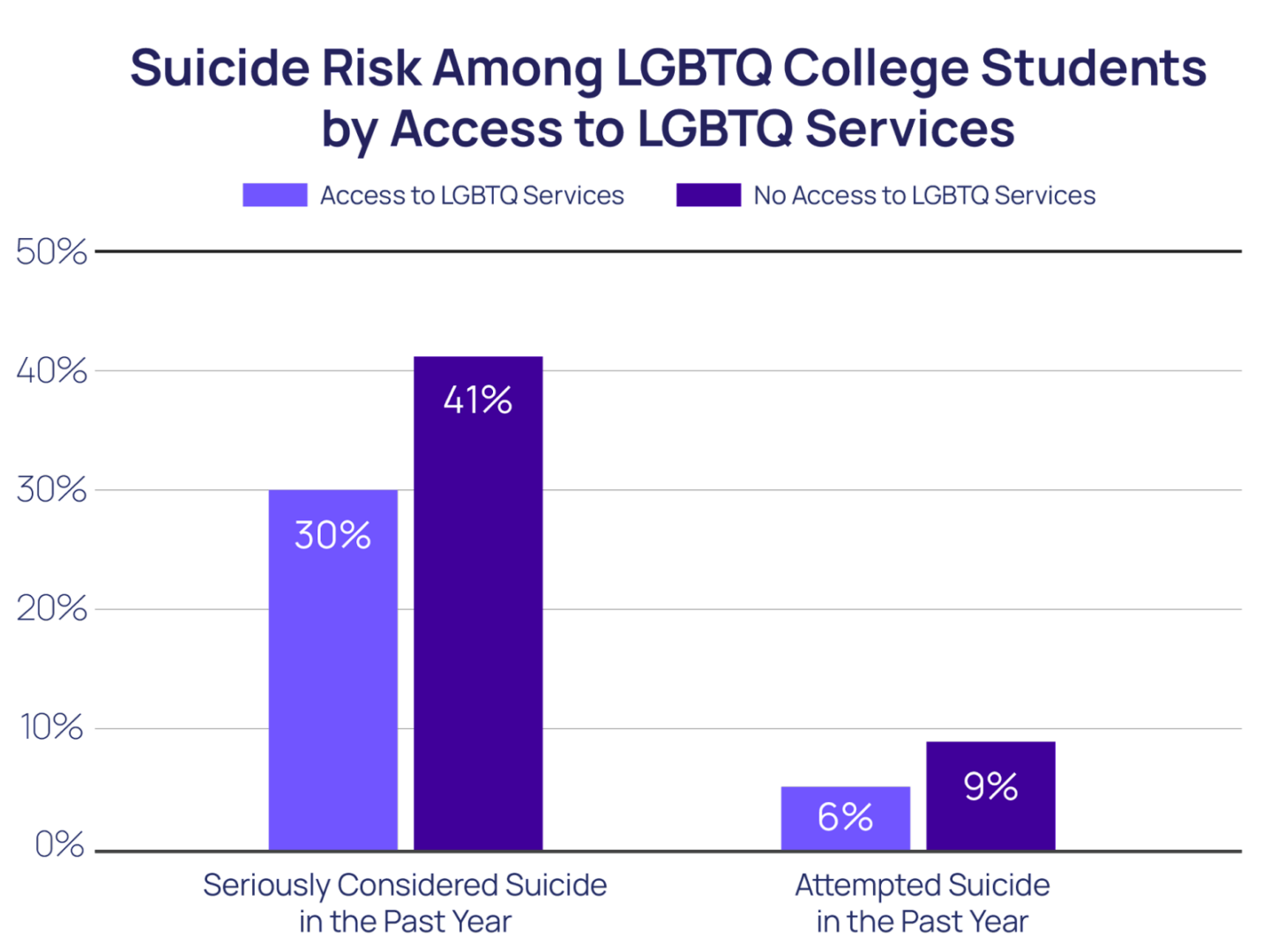

LGBTQ college students with access to LGBTQ student services through their college had 44% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 0.56) compared to LGBTQ college students without access. Over six in ten (63%) LGBTQ college students reported that their college had LGBTQ-specific services, such as an LGBTQ center, available. Compared to LGBTQ college students who reported that they had access to LGBTQ student services through their college (30%), those who did not have access to LGBTQ student services through their college reported significantly higher rates of seriously considering suicide in the past year (41%). Similarly, LGBTQ college students who did not have access to LGBTQ student services through their college (9%) reported significantly higher rates of attempting suicide in the past year compared to those who had access (6%).

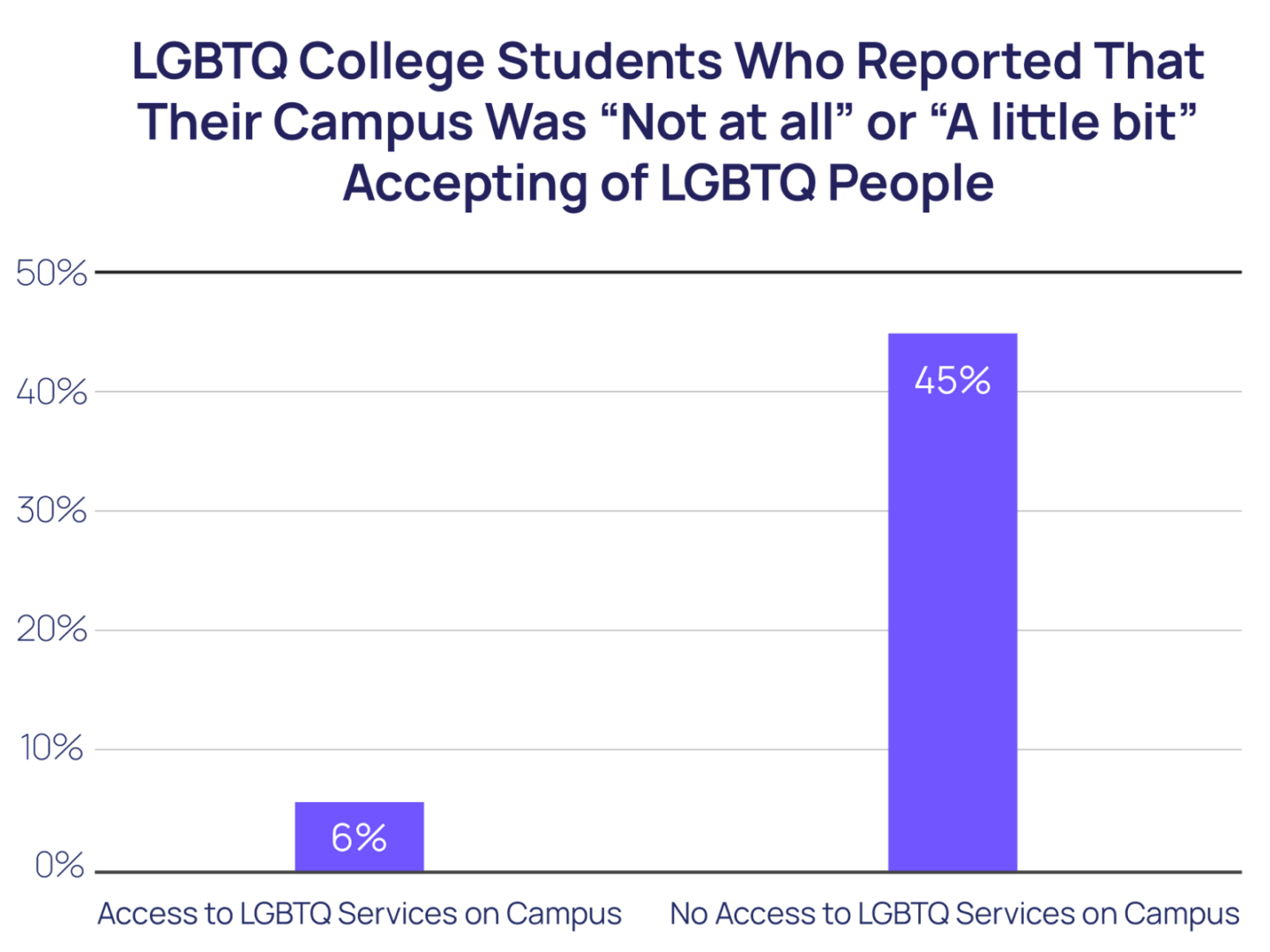

Nearly nine in ten LGBTQ college students (89%) reported that their college was accepting of LGBTQ people, and this was associated with the availability of LGBTQ-specific services. Nearly half of LGBTQ college students who did not have access to LGBTQ services through their college (45%) reported that their college was unaccepting of LGBTQ people, compared to only 6% of those who had access.

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2021 of 33,993 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. Survey respondents who indicated that they were currently enrolled in school were asked “What type of school are you enrolled in?” Respondents who selected either community/junior college, 4-year university, or graduate school were included in analyses. To assess whether youth’s college is accepting of LGBTQ people, students were asked, “How accepting is your college/university of LGBTQ people?” with response options of 1) Not at all, 2) A little bit, 3) Somewhat, and 4) A lot. To assess whether students have access to LGBTQ or mental health services through their college, youth were asked, “Does your college/university have LGBTQ services (e.g. an LGBTQ Center)?” and “Does your college/university offer mental health services to students?” with response options of 1) No, 2) Yes, and 3) I don’t know. The questions assessing past-year suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Separate adjusted logistic regression models were conducted to determine the association between having access to mental health services or LGBTQ services and attempting suicide in the past year, while controlling for age, race/ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and sexual identity.

Looking Ahead

Despite the potential presence of protective factors like affirming community and services, suicide risk persists among LGBTQ college students, especially on campuses that do not offer mental health and LGBTQ-specific student services. Suicide risk was highest among LGBTQ students of color, multisexual students, and transgender and nonbinary students. Specifically, LGBTQ students of color reported attempting suicide at 1.5 times the rate of their White LGBTQ peers, and transgender and nonbinary youth reported attempting suicide at more than twice the rate of their LGBQ cisgender peers. These data illuminate that LGBTQ college students who hold multiple marginalized identities likely face barriers and/or stigma compounding their minority stress not only based on their sexual orientation, but also based on their race/ethnicity and gender identity, among other marginalized identities.

Having access to mental health services and LGBTQ services through college is critical for reducing suicide attempts among LGBTQ college students. While the majority of LGBTQ college students reported that their college or university offered mental health services, and that their college or university was accepting of LGBTQ people, having access to mental health services and LGBTQ-specific services were associated with 84% and 44% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year, respectively. Colleges should be aware that making these services available, accessible, and affirming is critical to the mental health and well-being of LGBTQ students. Colleges should be mindful of utilizing gender-affirming language (Singh, Meng, & Hansen, 2013), providing inclusive and comprehensive physical and mental health care for LGBTQ students (Goldberg et al., 2019), and having LGBTQ-specific resources embedded into student health centers and counseling centers to make care more accessible to LGBTQ students (Aubrey et al., 2020). Campuses – especially those with small student bodies – must also make sure that their mental health and LGBTQ services can protect the privacy of LGBTQ students seeking support.

The Trevor Project is committed to finding ways for all LGBTQ young people to feel safe and supported. Our 24/7 crisis services are available in three different modalities – phone, chat, and text – so that youth in crisis have multiple avenues to communicate with culturally competent and affirming counselors. We offer our guide to Creating Safer Spaces in Schools for LGBTQ Youth on our website for those interested in learning how to support LGBTQ students. Our TrevorSpace platform also connects young people with supportive peers online, if they are struggling to find community in their current setting. Further, Trevor’s research, advocacy, and public training teams are focused on using data, policies, and education to enhance the ability of youth-serving professionals to understand and address the unique needs of LGBTQ young people pursuing higher education opportunities.

References

- Aubrey, J. S., Pitts, M. J., Lutovsky, B. R., Jiao, J., Yan, K., & Stanley, S. J. (2020). Investigating disparities by sex and LGBTQ identity:a content analysis of sexual health information on college student health center websites. Journal of Health Communication, 25(7), 584-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1825567

- Dunbar, M. S., Sontag-Padilla, L., Ramchand, R., Seelam, R., & Stein, B. D. (2017). Mental health service utilization among lesbian,gay, bisexual, and questioning or queer college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(3), 294–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.03.008

- Goldberg, A. E., Kuvalanka, K. A., Budge, S. L., Benz, M. B., & Smith, J. Z. (2019). Health care experiences of transgender binary andnonbinary university students. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(1), 59–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019827568

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

- Linley, J. L., Nguyen, D., Brazelton, G. B., Becker, B., Renn, K., & Woodford, M. (2016). Faculty as sources of support for LGBTQcollege students. College Teaching, 64(2), 55–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2015.1078275

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues andresearch evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

- Nguyen, D. J., Brazelton, G. B., Renn, K. A., & Woodford, M. R. (2018). Exploring the availability and influence of LGBTQ+ studentservices resources on student success at community colleges: A mixed methods analysis. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 42(11),783–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1444522

- Pitcher, E. N., Camacho, T. P., Renn, K. A., & Woodford, M. R. (2018). Affirming policies, programs, and supportive services: Using anorganizational perspective to understand LGBTQ+ college student success. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 11(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000048

- Rankin, S., Blumenfeld, W. J., Weber, G. N., & Frazer S. J. (2010). State of higher education for LGBT people: Campus pride 2010national college climate survey. Campus Pride.

- Singh, A. A., Meng, S., & Hansen, A. (2013). “It’s already hard enough being a student”: Developing affirming college environmentsfor trans youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 10(3), 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2013.800770

- Woodford, M. R., Weber, G., Nicolazzo, Z., Hunt, R., Kulick, A., Coleman, T., Coulombe, S., & Renn, K. A. (2018). Depression andattempted suicide among LGBTQ college students: Fostering resilience to the effects of heterosexism and cisgenderism on campus. Journal of College Student Development, 59(4), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0040

For more information please contact: [email protected]