EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Multiracial youth are the fastest-growing demographic in the United States (Jones et al., 2021); however, minimal research specifically explores multiracial youth’s mental health and well-being. Even less research explores the intersection of multiracial and LGBTQ identities, particularly among youth. The unique convergence of stressors experienced by holding a multiracial identity and an LGBTQ identity might make them more susceptible to negative experiences, and as a result, poorer mental health and well-being. This report is the first of its kind to explore the mental health and well-being of LGBTQ youth who are multiracial and provide within-group findings among multiracial LGBTQ youth to highlight different experiences among multiracial LGBTQ youth. This report uses data from a national sample of over 4,700 multiracial LGBTQ youth (14.6%) ages 13–24 who participated in The Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health.

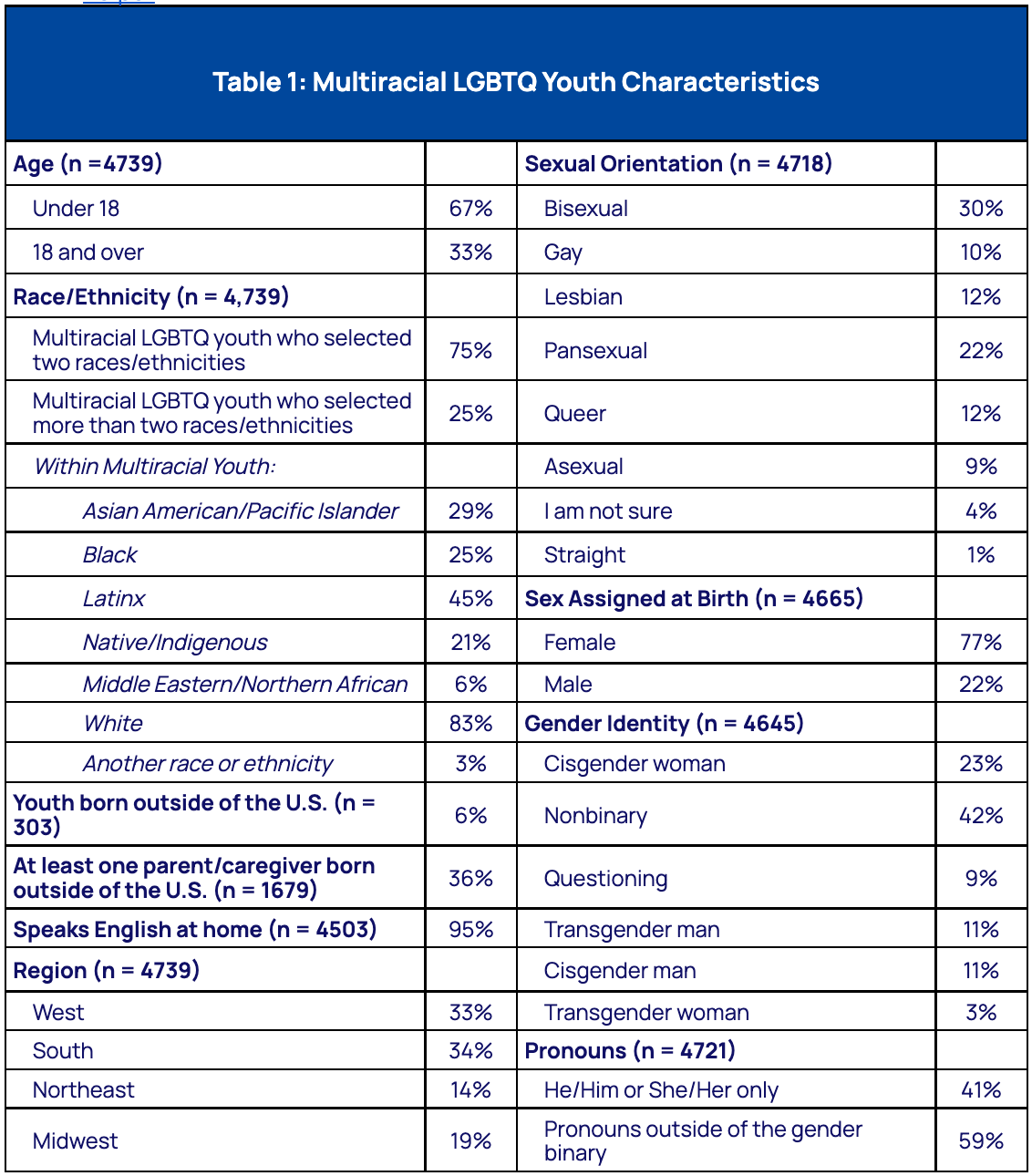

Multiracial LGBTQ youth are diverse in their racial, sexual, and gender identities.

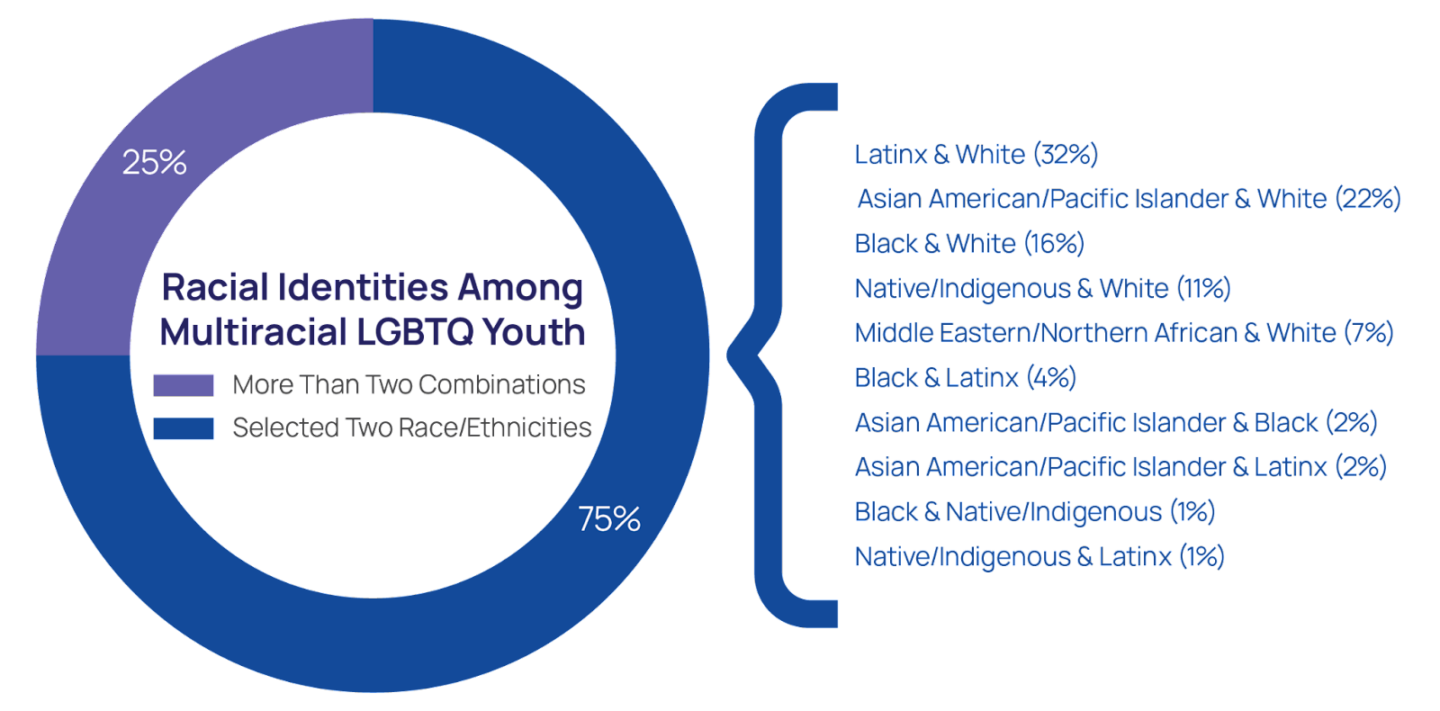

- 75% of multiracial LGBTQ youth identified with two races/ethnicities, and 25% with more than two

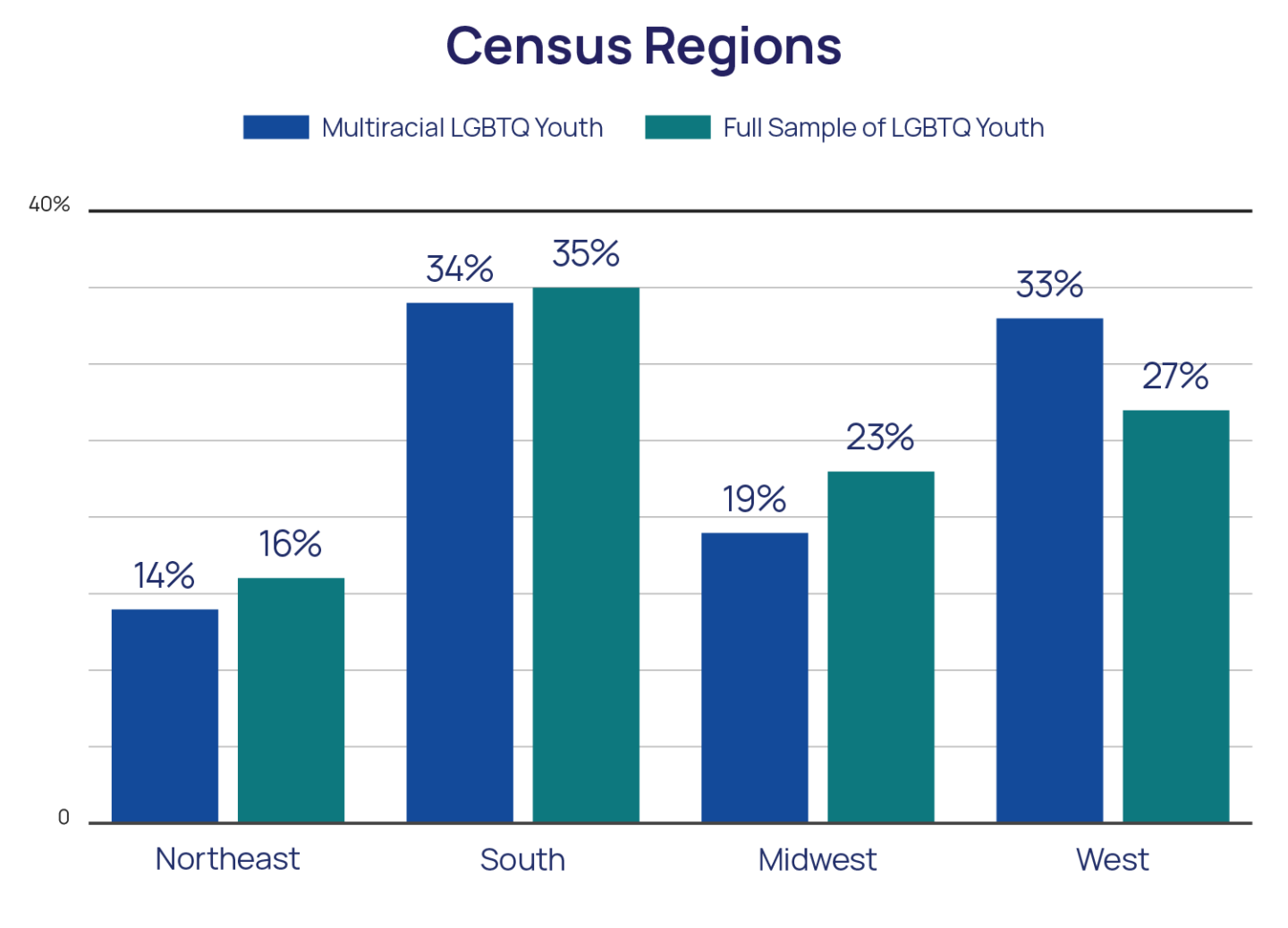

- Multiracial LGBTQ youth were more concentrated in the Western part of the U.S., compared to the overall LGBTQ youth sample

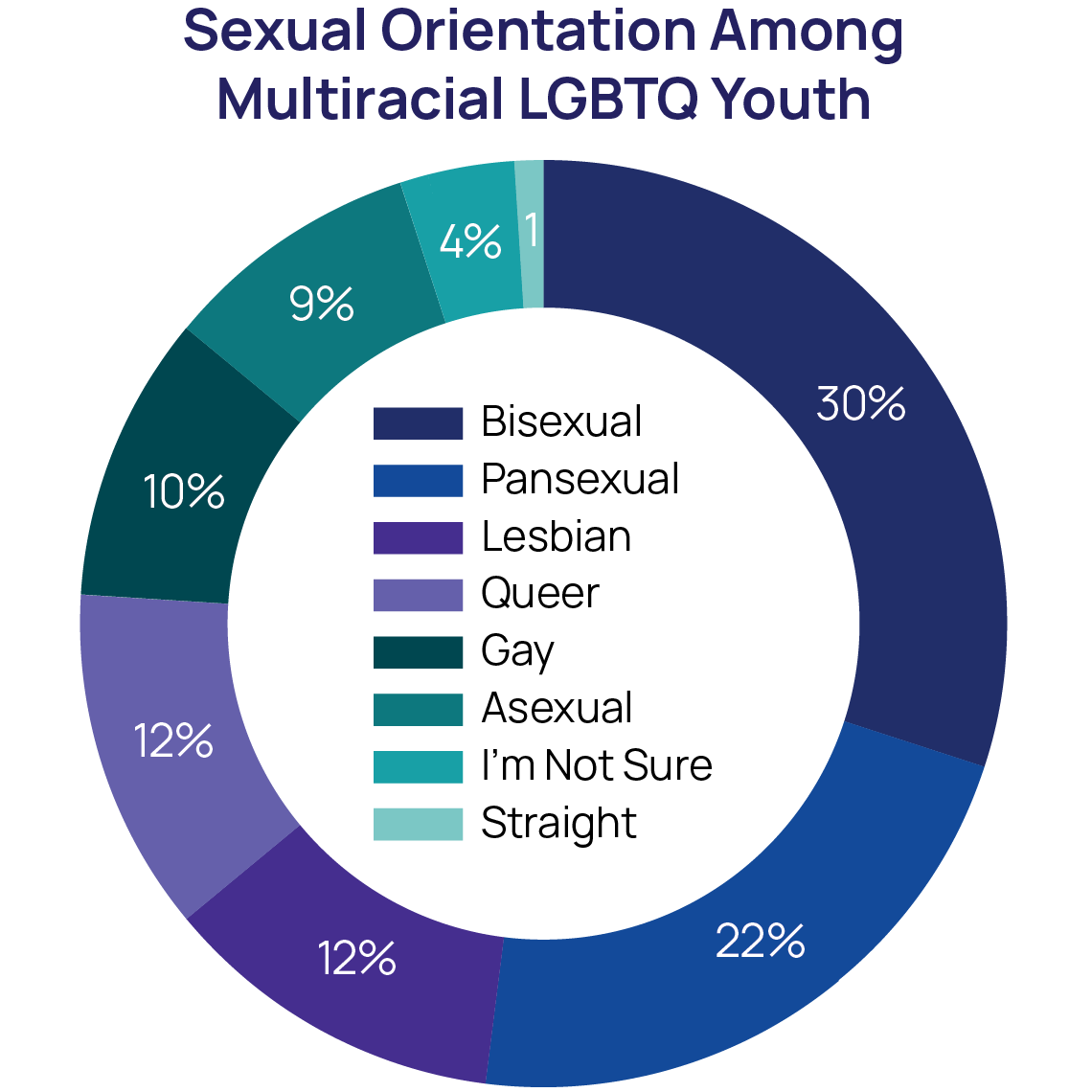

- 30% of multiracial LGBTQ youth were bisexual, 22% gay or lesbian, 21% pansexual, 12% queer, 10% asexual, and 1% straight

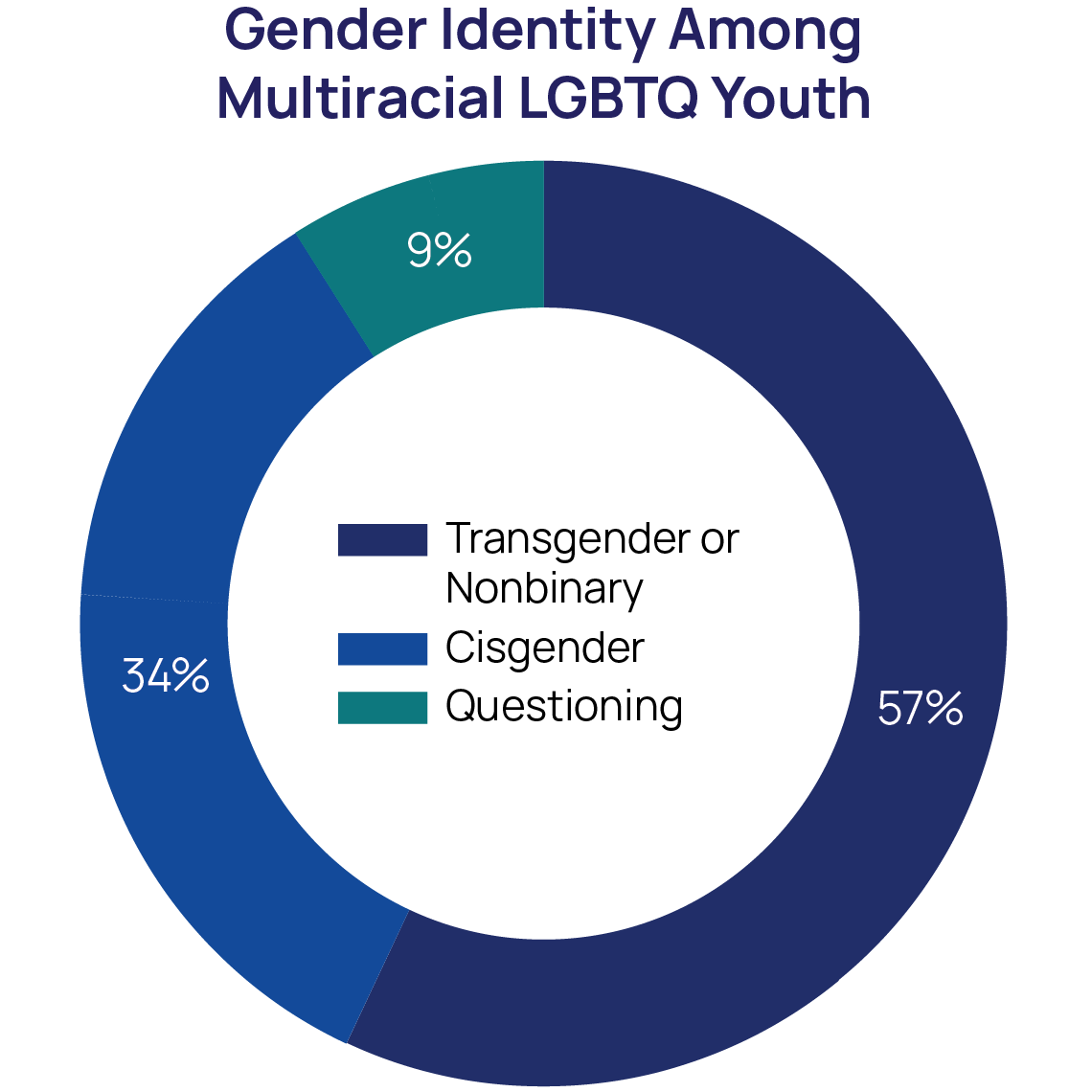

- 57% of multiracial LGBTQ youth identified as transgender or nonbinary, compared to 51% of the overall LGBTQ youth sample

Multiracial LGBTQ youth report higher rates of mental health challenges compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth.

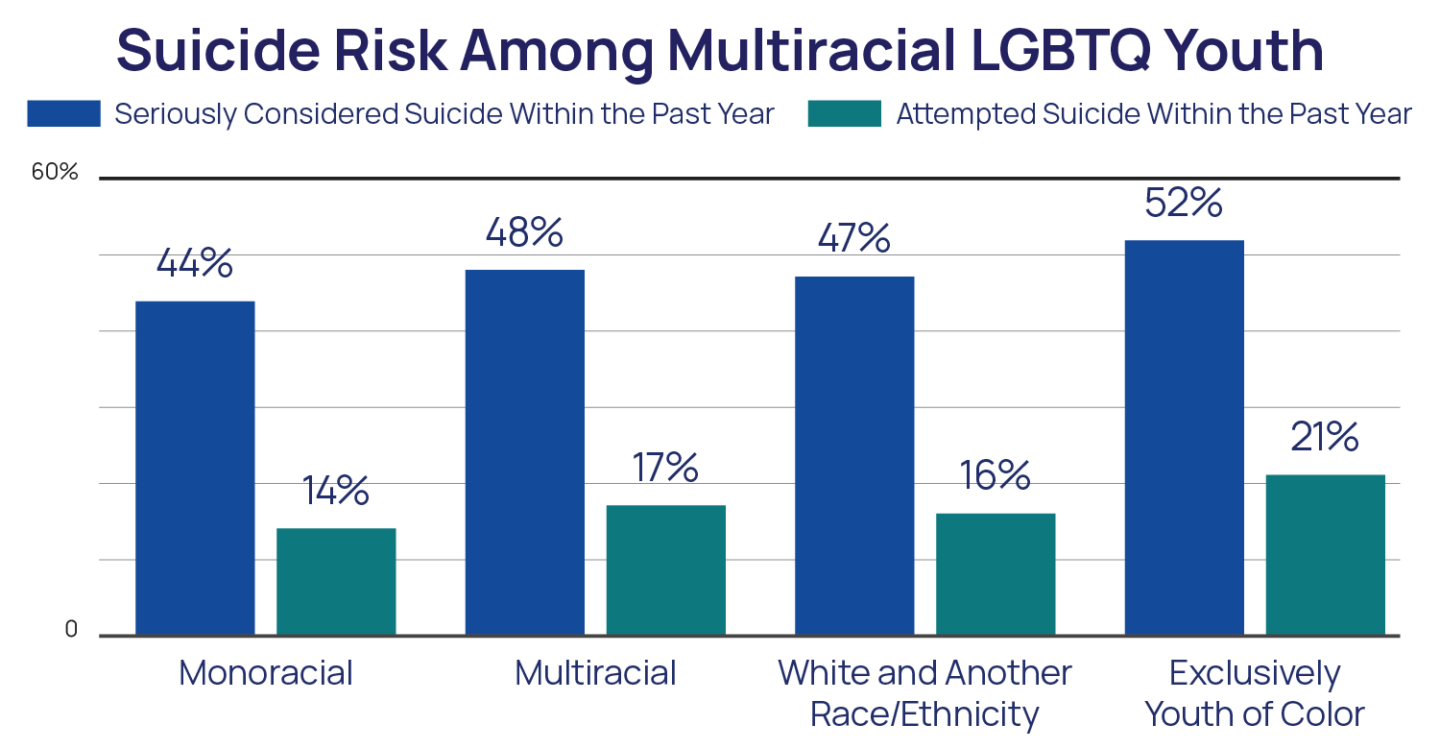

- 48% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported seriously considering suicide in the past year, including 55% of multiracial transgender and nonbinary youth

- 17% of multiracial LGBTQ youth attempted suicide in the past year, including 22% of multiracial transgender and nonbinary youth

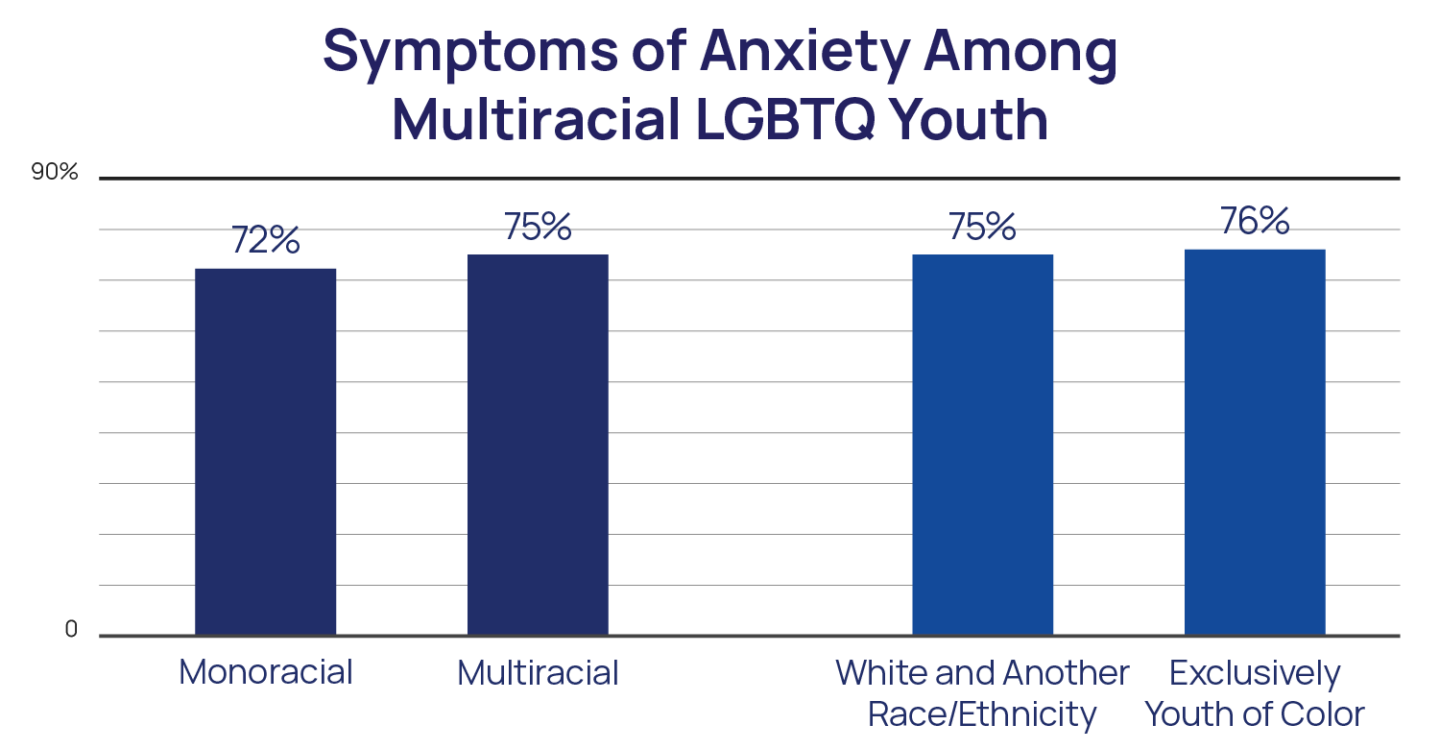

- 75% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported symptoms of anxiety in the past two weeks

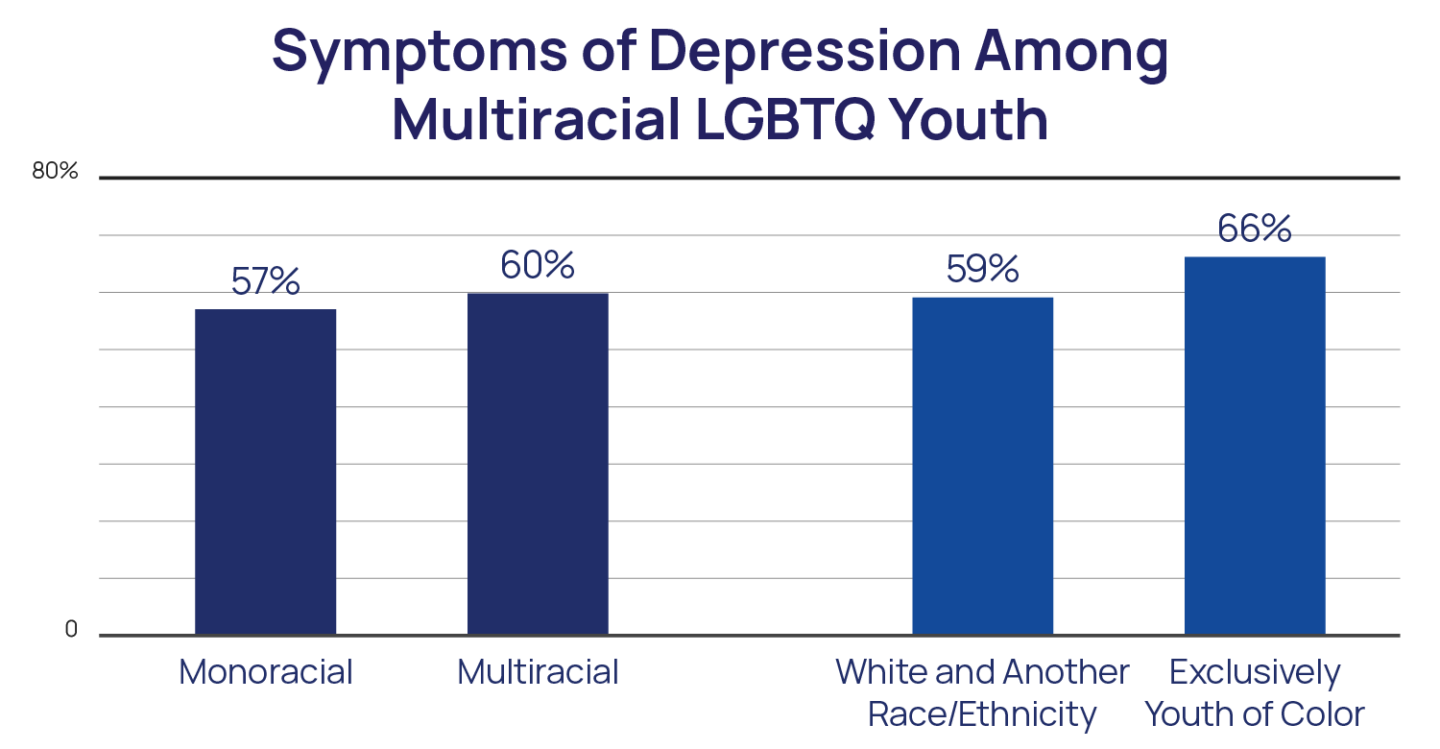

- 60% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported symptoms of depression in the past two weeks

- Multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color reported higher rates of symptoms of depression, seriously considering suicide, and attempting suicide compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity

Multiracial LGBTQ youth experience higher rates of risk factors for suicide compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth.

- 31% of multiracial LGBTQ youth have ever experienced homelessness, been kicked out, or run away

- 31% of multiracial LGBTQ youth have experienced food insecurity in the past month

- 39% of multiracial LGBTQ youth have experienced discrimination based on their race/ethnicity in the past year

- 77% of multiracial LGBTQ youth have ever experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity

- 35% of multiracial LGBTQ youth have ever been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation

- 40% of multiracial transgender and nonbinary youth have ever been physically threatened or harmed due to their gender identity

LGBTQ-affirming spaces and people are strong protective factors for multiracial LGBTQ youth suicide.

- Multiracial LGBTQ youth who reported high levels of social support from family had 55% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year

- Multiracial LGBTQ youth with high social support from friends reported lower rates of attempted suicide in the past year compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth without it

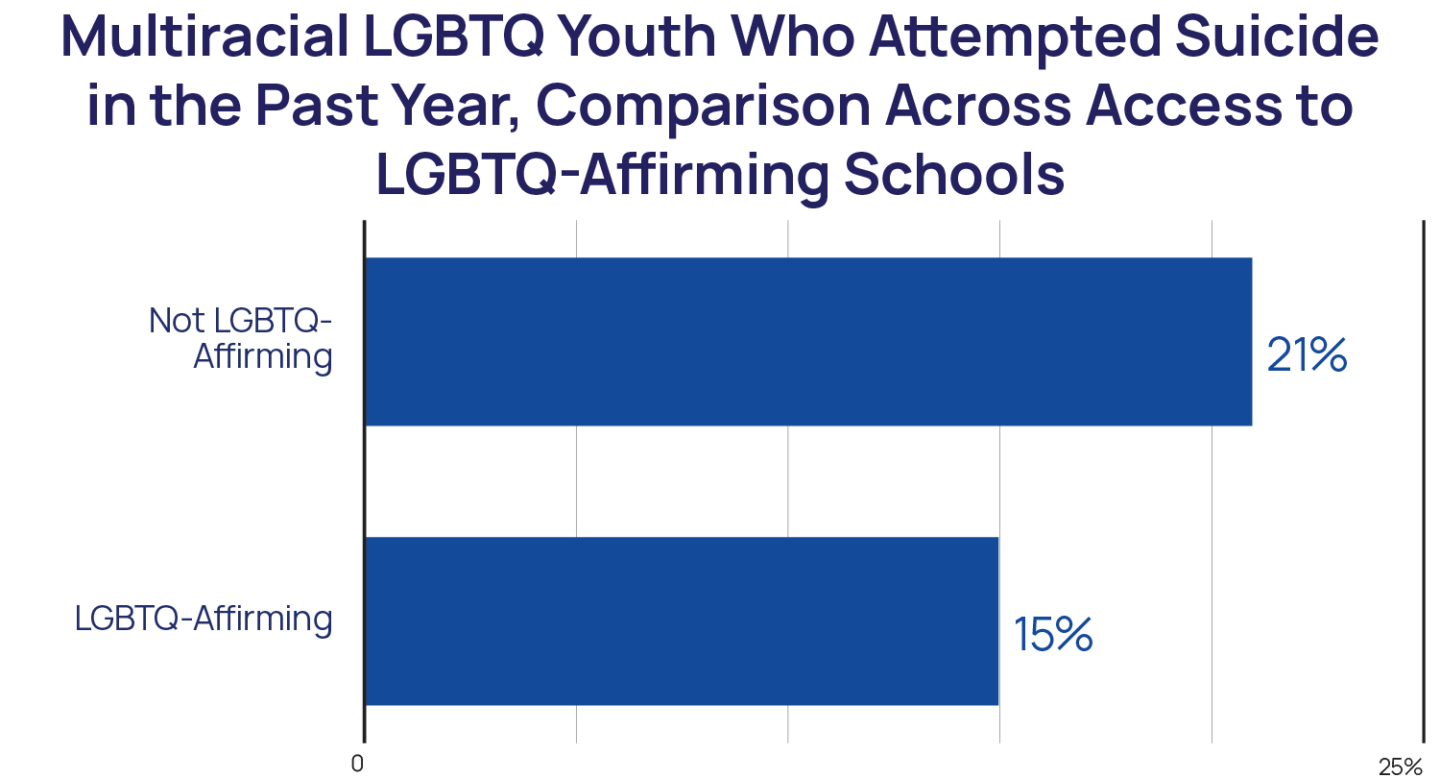

- Multiracial LGBTQ youth who attend LGBTQ-affirming schools had a 33% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year

Methodology Summary

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data using an online survey platform between September and December 2021. An analytic sample of nearly 34,000 youth ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. All youth respondents were asked, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, more than one race or ethnicity, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, White/Caucasian, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Youth who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question where they were able to select with which races or ethnicities they identified. The current analyses include the 4,739 LGBTQ youth who selected more than one race or ethnicity, henceforth referred to as multiracial. While we understand that definitions can vary given the social constructs of both race and ethnicity, in this report, we refer to multiracial youth as youth with parents from different racial and/or ethnic backgrounds.

Recommendations

The issues faced by multiracial LGBTQ youth are stark and underreported. Multiracial LGBTQ youth report rates of mental health challenges that are higher than monoracial LGBTQ youth. Unsurprisingly, multiracial LGBTQ youth also report higher rates of many risk factors for poor mental health compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth. Multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color were particularly vulnerable, highlighting the potential role of racism in poor mental health among youth of color. Researchers and stakeholders must do more to examine and dismantle systematic racism and to prioritize the well-being of multiracial LGBTQ youth in order to inform best practices for working with this population and to improve outcomes. Youth-serving organizations must create supportive and accepting environments where multiracial identities are validated and LGBTQ identities are affirmed.

BACKGROUND

Research consistently finds that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth face higher rates of poor mental health compared to their straight and cisgender peers. LGBTQ youth report higher rates of anxiety and depression and are also more likely to engage in self-harm, seriously consider suicide, and attempt suicide when compared to straight, cisgender youth (Johns et al., 2020). These higher rates are not due to being LGBTQ in and of itself, but are instead due to chronic stress stemming from negative experiences associated with having a marginalized social status in society (Meyer, 2003). LGBTQ youth often face stressors such as rejection, victimization, bullying, and discrimination (Kosciw et al., 2018), in addition to common stressors faced by most youth, which can then lead to internalized homophobia, perceived burdensomeness–belief that other would be better off if they were gone–(Baams et al., 2015), and poor mental health. That said, important differences exist among LGBTQ youth, particularly among LGBTQ youth who hold multiple marginalized identities. For example, research finds that transgender and nonbinary youth report rates of poor mental health outcomes that are not only higher than cisgender youth (Johns et al., 2019), but higher when compared to cisgender LGBQ youth as well (Price-Feeney et al., 2020), as do youth who are bisexual or multisexual (Price et al., 2021). Important intersectional differences also exist among LGBTQ youth who hold multiple marginalized identities, such as youth who are multiracial and LGBTQ, which can increase their risk for poor mental health.

Multiracial youth may face unique experiences and challenges that put them at increased risk for psychological distress. Multiracial youth have experiences with parents from different backgrounds, such as language, customs, worldviews, and life experiences, and have to navigate those as well as interactions with extended family members. This can contribute to learning early on how to navigate a wider range of diverse individuals or circumstances compared to monoracial youth, or youth whose parents are of the same racial/ethnic background (Nishina & Witkow, 2020). However, multiracial youth rarely find themselves in situations where they are the majority, and there are no official U.S. cultural events or holidays that celebrate multiracial identities and individuals. Though there have been recent improvements, because multiracial public figures are often assumed to be or are absorbed into broader monoracial groups, there is often a lack of multiracial role models for youth (Shih & Sanchez, 2005). Additionally, multiracial individuals report unique experiences with marginalization due to society’s emphasis on rigid racial categories, which may cause others to express confusion about their race/ethnicity, and not be fully embraced by any particular racial group (Navarrete & Jenkins, 2011). Multiracial individuals may experience pressure, both internal and external from others, to choose one part of their background with which to identify (Herman, 2004). Therefore, unlike monoracial youth, multiracial youth have the added task and potential stressor of integrating multiple identities. Otherwise known as multiracial identity invalidation, having one’s racial identity be invalidated by others can lead to multiracial individuals feeling disconnected from communities that may be important to them and influence mental health (Franco & O’Brien, 2018; Rockquemore et al., 2009). Finally, multiracial youth still have to contend with negative experiences due to their race/ethnicity like other monoracial youth of color in the U.S. (Samuels, 2014).

The stressors experienced at the intersection of a multiracial identity and an LGBTQ identity might even further increase the risk for poor mental health challenges. An intersectional perspective suggests that a person’s position or social location in society, based on social demographics such as race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and ability, among others, affords unique experiences for people, particularly those with multiple marginalized identities (Collins & Bilge, 2020). The unique intersectionality of multiracial people who are LGBTQ is rarely addressed in research. However, those that have explored this intersectionality in research have found that multiracial LGBTQ people are subjected to both rejection and invisibility within their racial communities (Navarrete & Jenkins, 2011) and racism and mistreatment by the LGBTQ community (Elkhadem & Smith, 2016), which may create an added barrier to finding connectivity and support in the LGBTQ community (Felipe et al., 2022). As such, multiracial LGB people report higher rates of depression, self-harm, considering suicide, and suicide attempts compared to multiracial straight people, and higher rates of self-harm and suicide attempts compared to non-Hispanic White LGB people (Lytle et al., 2014). Even less research examines the specific experiences of multiracial LGBTQ youth, often only including them in the context of research on other LGBTQ youth. For example, a study of microaggressions among high school students found that both Black and multiracial LGBTQ students reported more race-based experiences of microaggressions than their straight peers (Banks et al., 2022). Additionally, in GLSEN’s series, “Erasure and resilience: The experiences of LGBTQ students of color,” the researchers often aggregated their analyses by monoracial youth and multiracial youth, providing insight into how they compare. For example, multiracial AAPI LGBTQ students reported having fewer supportive staff, more victimization based on sexual orientation and gender identity, more in-school discipline, and higher severity of racist victimization compared to exclusively AAPI LGBTQ students (Truong et al., 2020).

Primarily due to White privilege and a youth’s proximity and access to it, the experiences of all multiracial LGBTQ youth may not be the same. Race continues to be a significant and well-documented factor in determining inequity in the United States, with institutional and structural racism disproportionately impacting people of color (Ladson-Billings & Tate IV, 1995). In this sense, there are political, economic, legal, political, and psychological advantages to being White, termed White privilege (Blacksher & Valles, 2021). The tenants of both of these argue that while people who are White may experience hardships, they do not encounter the additional hardships experienced by people of color due to societal racial bias. Using this argument, it could be presumed that all multiracial youth’s experiences in society may not be the same. In fact, youth who are able to access White privilege, perhaps by having a White parent or by being perceived as being exclusively White, may benefit from racialized social systems while multiracial youth who are exclusively youth of color may not. While very little research specifically explores this, one study found that LGBTQ youth who identified as Native and White were least likely to feel unsafe about their race/ethnicity at school, followed by those who identified exclusively as Native, with other Native multiracial LGBTQ students feeling most unsafe regarding their race/ethnicity at school (Zongrone et al., 2020). The authors suggested this was perhaps because of their perception by others as being a person of color.

Research has failed to consider the mental health and well-being of multiracial LGBTQ youth and how they might experience various risk and protective factors. Often citing sample size, quantitative research on the experiences of LGBTQ youth frequently fails to explore the specific experiences of many groups who are smaller in size, such as multiracial youth. Furthermore, research on multiracial youth often does not consider how sexual orientation and gender identity may influence their findings or insights (Nishina & Witkow, 2020), leaving multiracial LGBTQ youth’s mental health dramatically unaddressed in research. Therefore, little is known about multiracial LGBTQ youth, let alone their mental health and well-being, and as such, their specific needs are unknown and often overlooked. This report is the first to exclusively study LGBTQ youth who are multiracial by describing the mental health and well-being of a national U.S. sample of over 4,700 multiracial LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who participated in our 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health.

METHODOLOGY

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data through an online survey platform between September and December 2021. A sample of LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. The final analytic sample consisted of 33,993 LGBTQ youth. In the survey, all youth were asked, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, more than one race or ethnicity, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, White/Caucasian, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Youth who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question to select with which races or ethnicities they identified. The current analyses include the 4,739 LGBTQ youth who selected more than one race or ethnicity, henceforth referred to as multiracial. While we understand that definitions can vary given the social constructs of both race and ethnicity, in this report, we refer to multiracial youth as youth with parents from different racial and/or ethnic backgrounds. The overall survey included a maximum of 150 questions, including questions on considering and attempting suicide in the past 12 months taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020) and measures of anxiety and depression based on the GAD-2 and PHQ-2, respectively (Plummer et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2010). Each analysis was run separately for multiracial youth who identified as White and another race/ethnicity (83%) compared to youth who are exclusively multiracial youth of color to explore within-group differences. Logistic regression models were used to predict attempting suicide in the past year, adjusting for sex assigned at birth, age, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

RESULTS

Diversity Among Multiracial LGBTQ Youth

Race, Ethnicity, Immigration, and Location

Multiraciality is a pan-ethnic and broad category that encompasses many different groups with different cultures and experiences, and the multiracial LGBTQ youth in our sample represented many of those. In our sample, 75% of multiracial LGBTQ youth identified with two races/ethnicities, and 25% identified with more than two (see sample demographics on Page 29). Among youth who selected two race/ethnicities, the most endorsed were 32% who identified as Latinx and White, 22% as Asian American/Pacific Islander and White, 16% as Black and White, 11% as Native and White, 7% as Middle Eastern/Northern African and White, and 4% as Black and Latinx. Overall, 83% of multiracial LGBTQ youth identified as White multiracial (White and one or more additional races or ethnicities), and 17% identified as exclusively multiracial youth of color.

Overall, 6% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported being born outside of the U.S. This compares to 7% of the overall sample of LGBTQ youth. Additionally, 36% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported that their parents were born outside of the U.S., compared to 27% of the overall LGBTQ youth sample. The vast majority of multiracial LGBTQ youth in our sample reported primarily speaking English at home (95%).

Multiracial LGBTQ youth were equally located in both the southern (34%) and western (33%) regions of the U.S., followed by the Midwest (19%) and northeastern U.S. (14%). While the proportion in the South is similar (35%), the overall LGBTQ youth sample had higher representation in the Midwest (23%) and Northeast (16%), and less in the West (27%).

Sexual Orientation

Mirroring the sexual orientations of the overall LGBTQ youth sample, the most frequent sexual orientation among multiracial LGBTQ youth was bisexual (30%), followed by over one in five multiracial LGBTQ youth (22%) who identified as gay or lesbian. An additional 22% of multiracial LGBTQ youth identified as pansexual, 12% as queer, 9% asexual, 1% as straight, and 4% were unsure of their sexual orientation.

Gender Identity and Expression

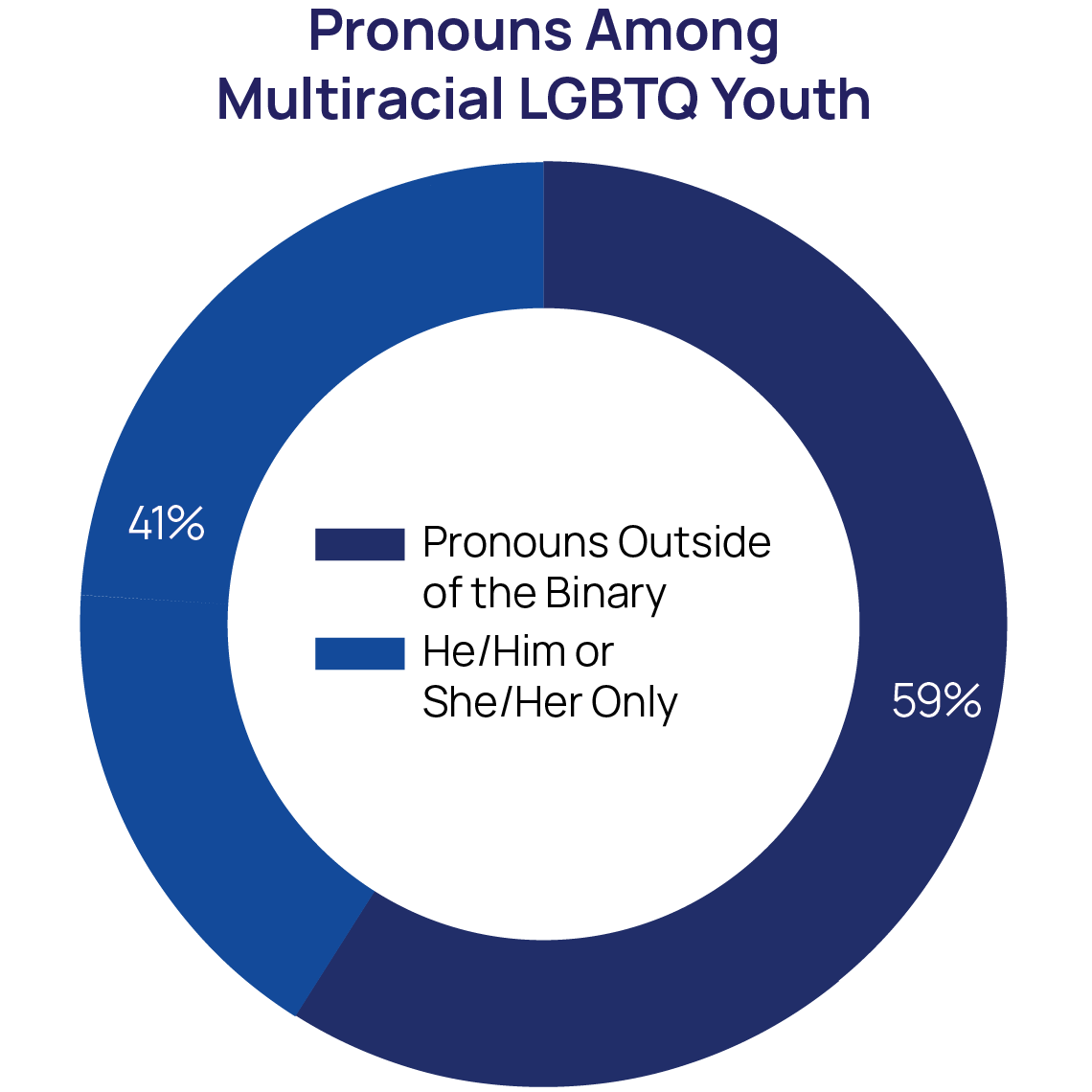

In our sample, 57% of multiracial LGBTQ youth identified as transgender or nonbinary. Multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity reported lower rates of being transgender or nonbinary (56%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ who are exclusively youth of color (61%). Additionally, 59% of the multiracial LGBTQ youth in our sample used pronouns or pronoun combinations that fell outside of the binary construction of gender, such as they/them exclusively or a combination of they/them and she/her or he/him. In contrast to sexual identity, rates of multiracial youth’s gender identities and expression differed compared to that of the overall sample of LGBTQ youth, 51% of whom were transgender or nonbinary, and 54% of whom used pronouns that fell outside of the binary construction of gender.

Mental Health and Well-Being Among Multiracial LGBTQ Youth

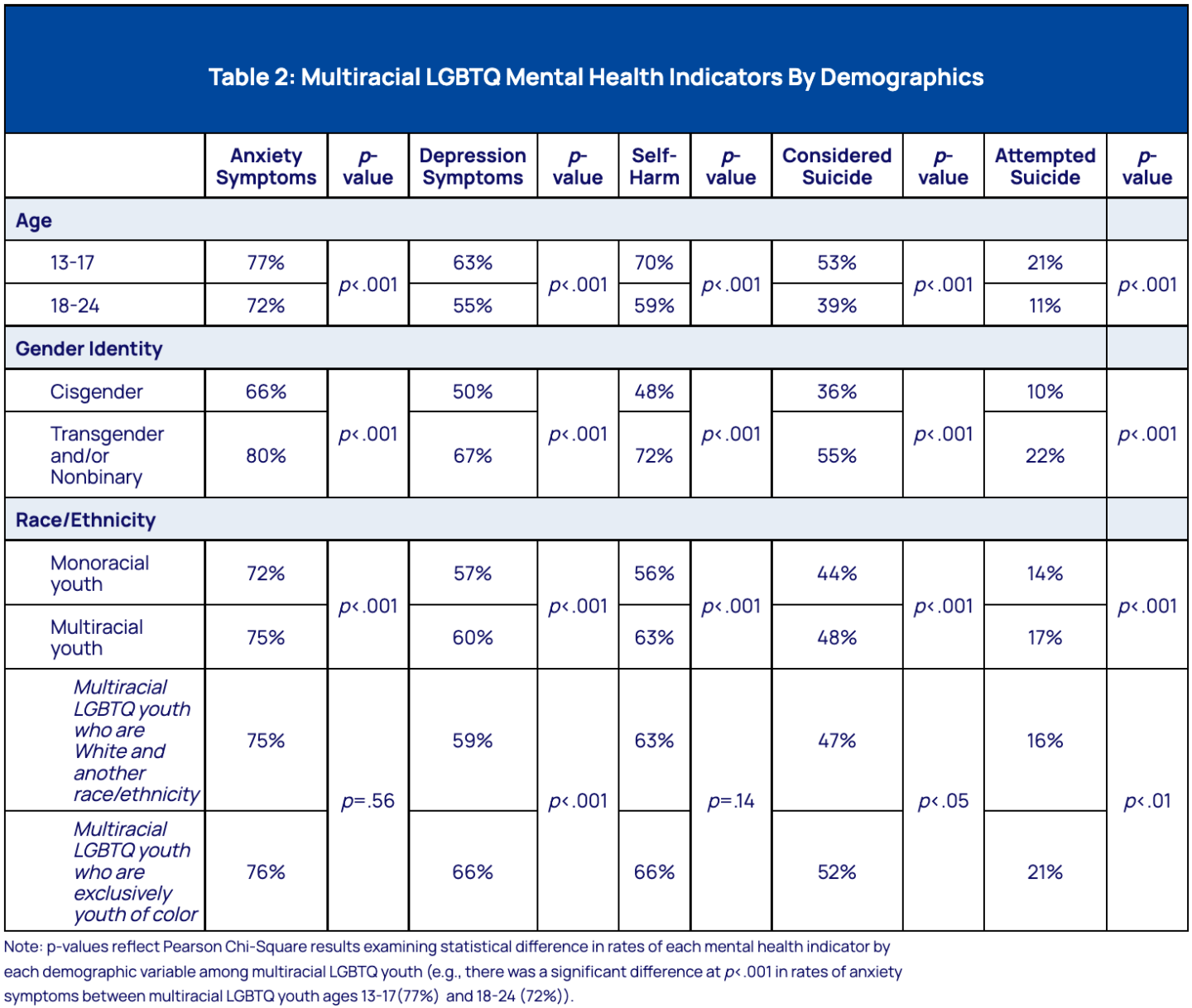

Anxiety and Depression

Multiracial LGBTQ youth reported rates of anxiety and depression that were higher than those reported by monoracial LGBTQ youth. Three out of four multiracial LGBTQ youth reported symptoms of anxiety in the past two weeks (75%). This compares to 72% of monoracial LGBTQ youth. See Table 2 (page 30) for how rates differed for multiracial transgender and nonbinary youth compared to cisgender multiracial LGBTQ youth, multiracial youth aged 13–17 compared to multiracial youth aged 18–24, and multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity compared to multiracial LGBTQ who are exclusively youth of color.

Overall, three in five multiracial LGBTQ youth reported symptoms of depression in the past two weeks (60%). Similar to anxiety, depression symptoms were higher among multiracial LGBTQ youth compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth (57%), and within-group differences can be found in Table 2 (page 30). However, multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color (66%) reported higher rates of symptoms of depression compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity (59%).

Self-Harm and Suicide Risk

Self-harm, also termed nonsuicidal self-injury or hurting one’s self on purpose, in the past year was reported by 63% of multiracial LGBTQ youth. This compares to 56% of LGBTQ youth who were monoracial. Furthermore, there were significant disparities by age and gender identity, with multiracial youth ages 13–17 and transgender and nonbinary youth reporting higher rates of self-harm compared to multiracial youth aged 18–24 and cisgender (Table 2).

Multiracial LGBTQ youth reported higher rates of suicide risk compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth. Nearly half (48%) of multiracial LGBTQ youth seriously considered suicide in the past year, which was higher when compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth (44%). Additionally, 17% of multiracial LGBTQ youth attempted suicide in the past year, compared to 14% of monoracial LGBTQ youth. Multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color reported higher rates of both seriously considering (52%) and attempting suicide (21%) in the past year compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity (Table 2).

It is important to note that, likely due to the complexities of race and stigma in the U.S., there are important differences even within multiracial youth who are White and another race/ethnicity, with LGBTQ youth who were Native and White often reporting significantly higher rates of nearly all mental health indicators and Asian American/Pacific Islander and White reporting the lowest.

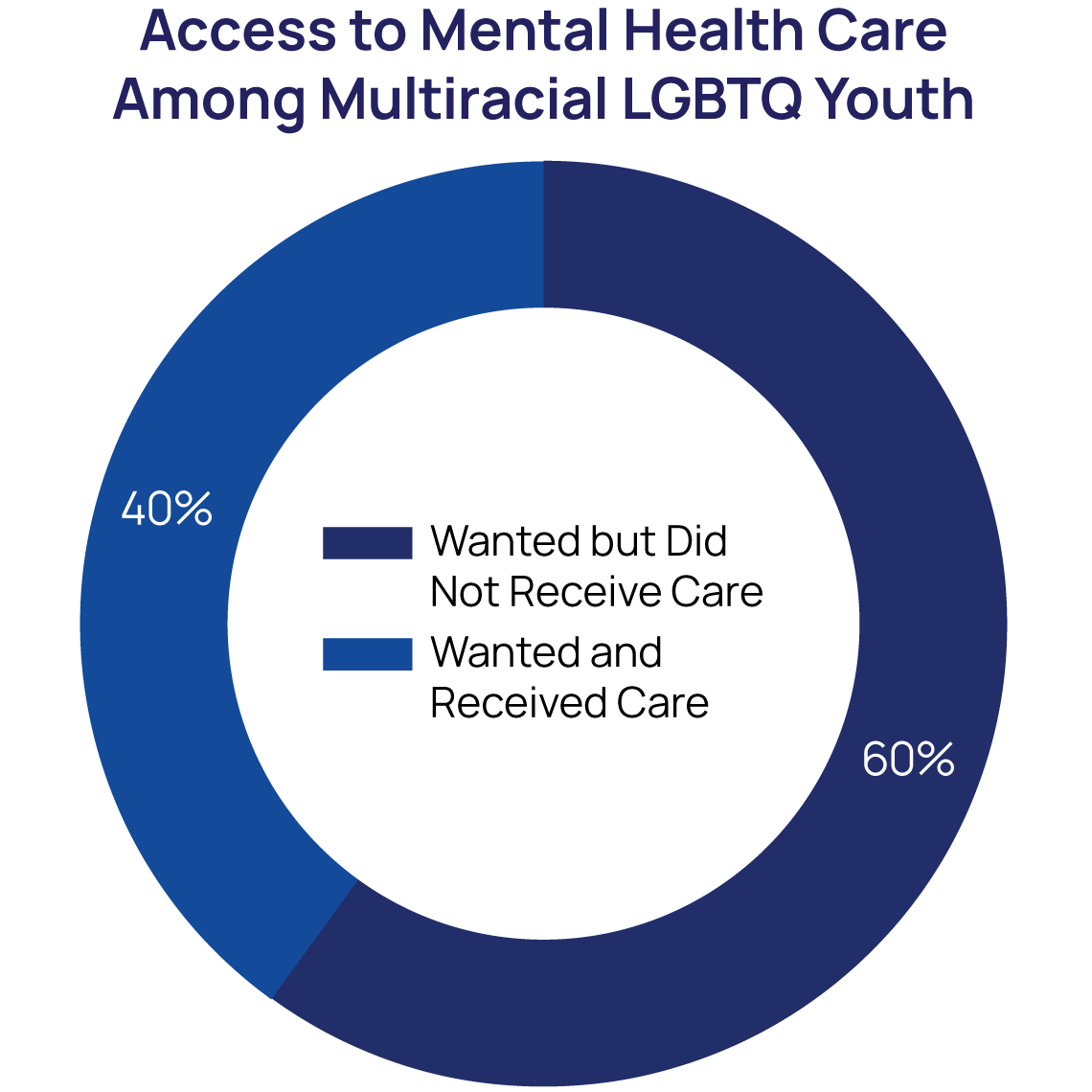

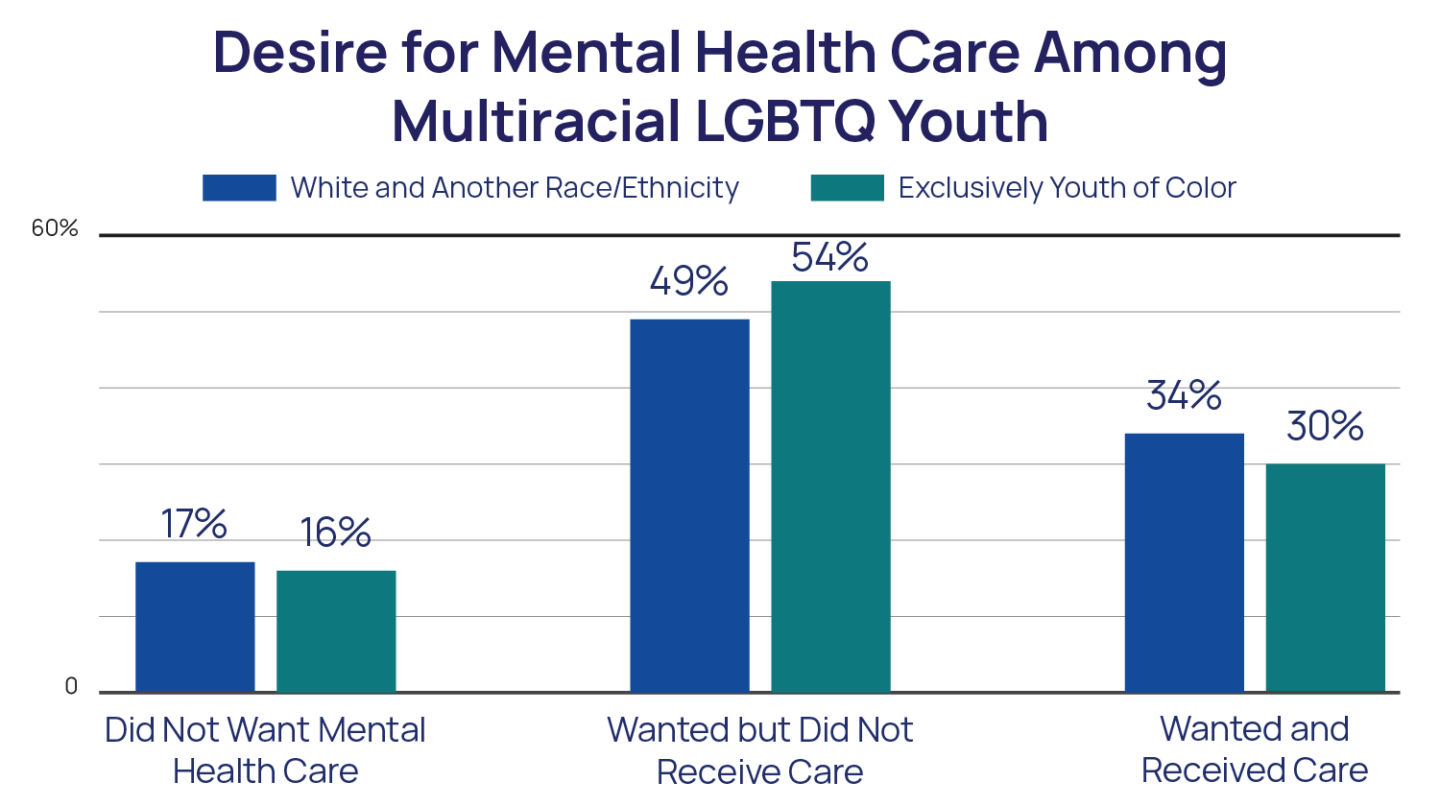

Access to Mental Health Care

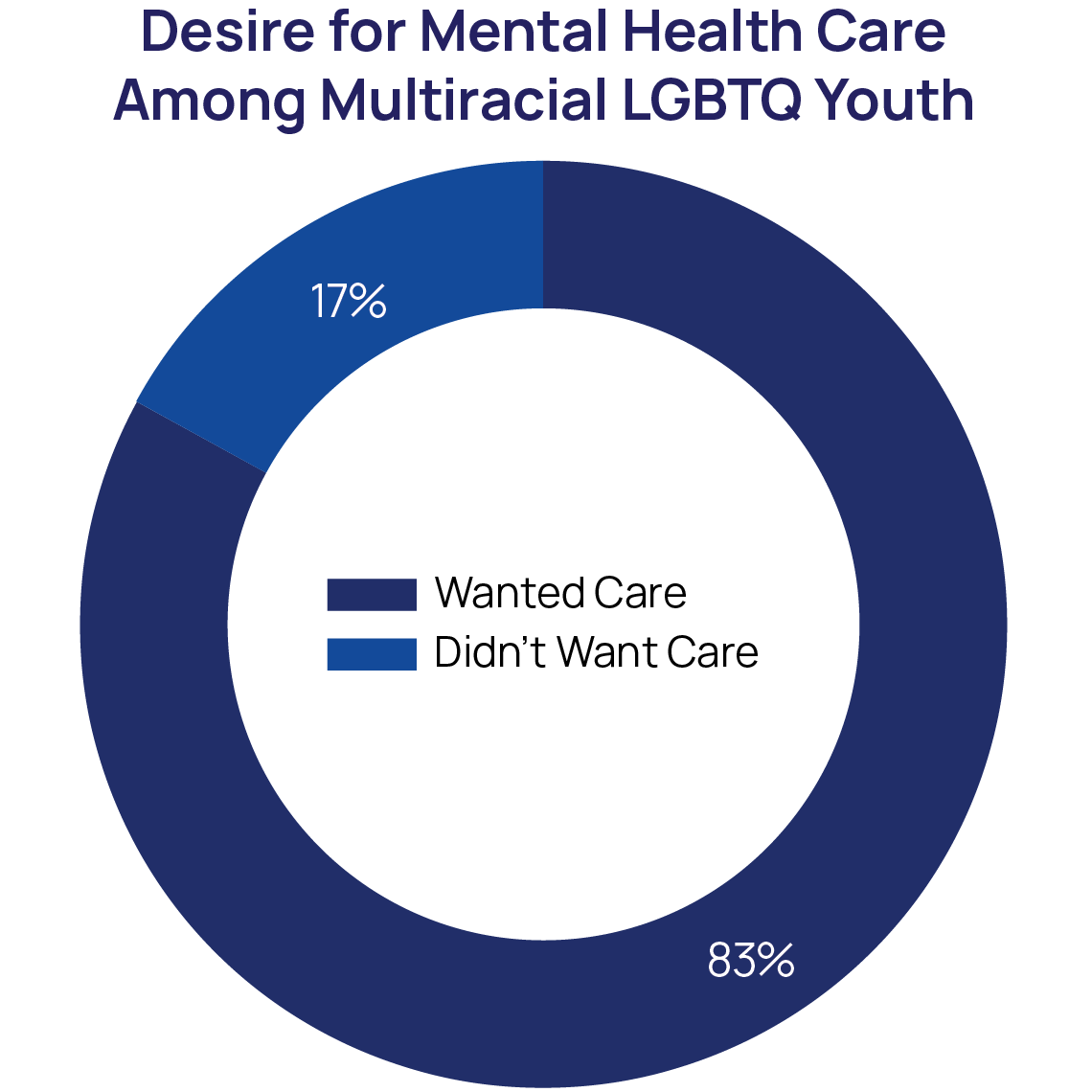

In spite of the rates of mental health concerns that are higher than monoracial LGBTQ youth, multiracial LGBTQ youth reported the same rates of experiencing barriers to access to wanted mental health care as their monoracial LGBTQ peers. Indeed, 60% of multiracial LGBTQ youth who wanted mental health care were not able to get it, matching the rate among the full sample. Half of multiracial LGBTQ youth (50%) reported wanting psychological or emotional counseling but were unable to receive it in the past 12 months compared to 33% of multiracial LGBTQ youth who wanted it and received it. Among multiracial youth, 54% of multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color reported wanting psychological or emotional counseling but being unable to receive it in the past year, despite reporting higher rates of nearly all mental health outcomes — in comparison to 49% of multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity. This finding further highlights the important disparities that can exist within this group.

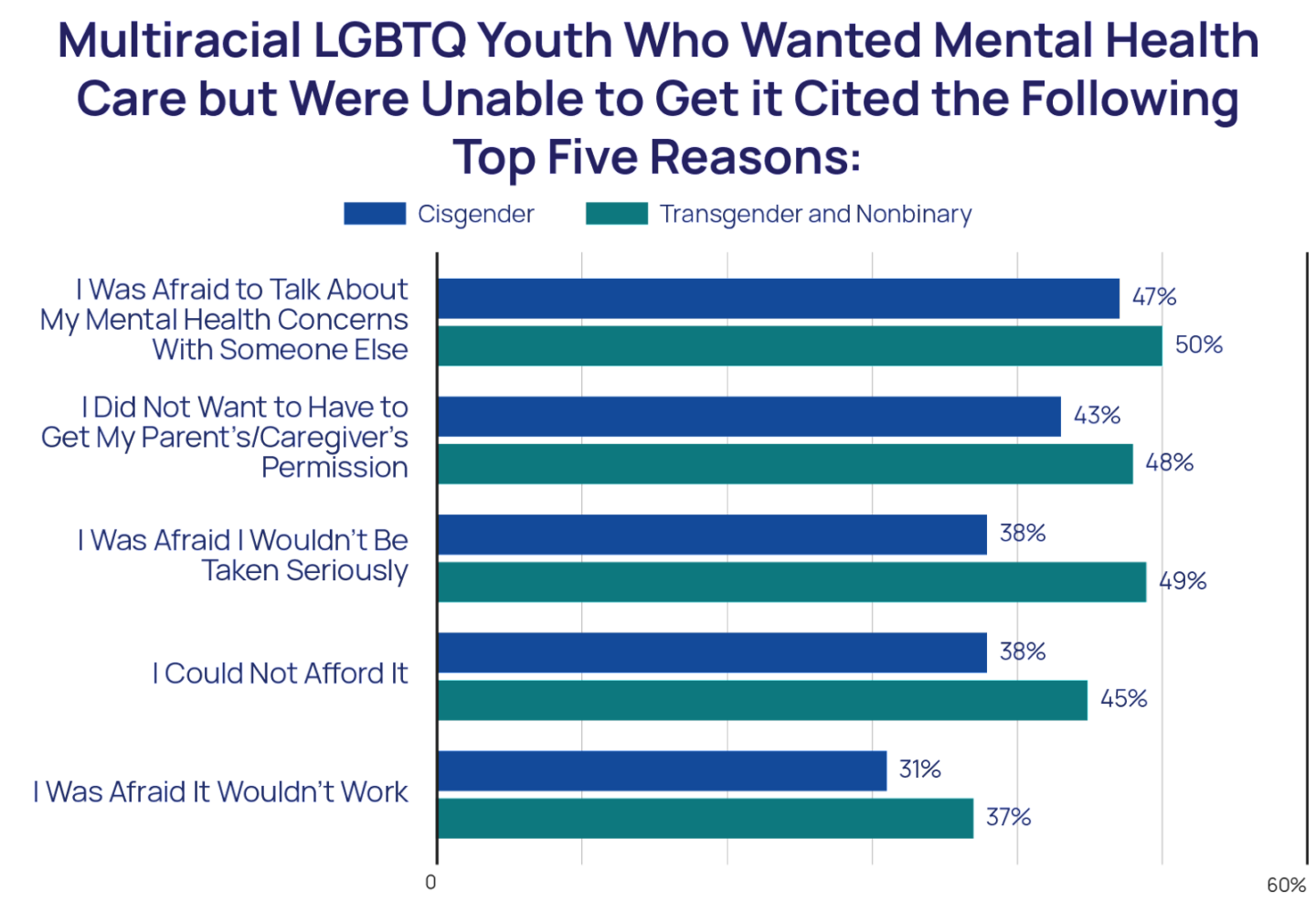

Multiracial LGBTQ youth reported similar barriers to access to mental health as the rest of the LGBTQ youth sample, with nearly half citing that they were afraid to talk about their mental health concerns with someone else (50%). Youth also reported that they did not want to get their parent’s/caregiver’s permission (46%), were afraid they wouldn’t be taken seriously (45%), could not afford it (42%), and that they were afraid it wouldn’t work (36%). Transgender and nonbinary multiracial youth reported significantly higher levels of nearly every barrier to mental health care compared to their multiracial cisgender peers.

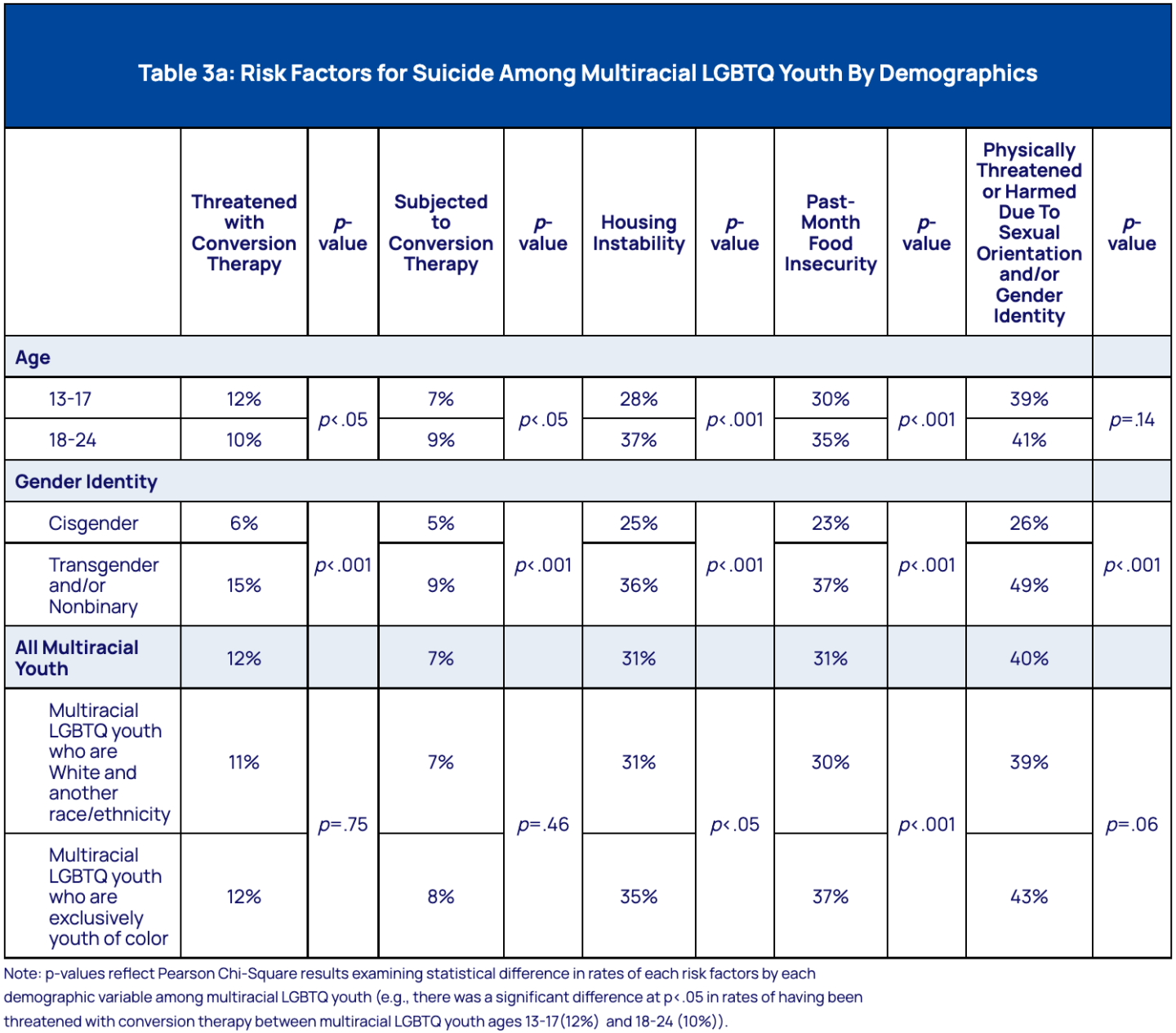

Risk Factors for Suicide Among Multiracial LGBTQ Youth

Conversion Therapy

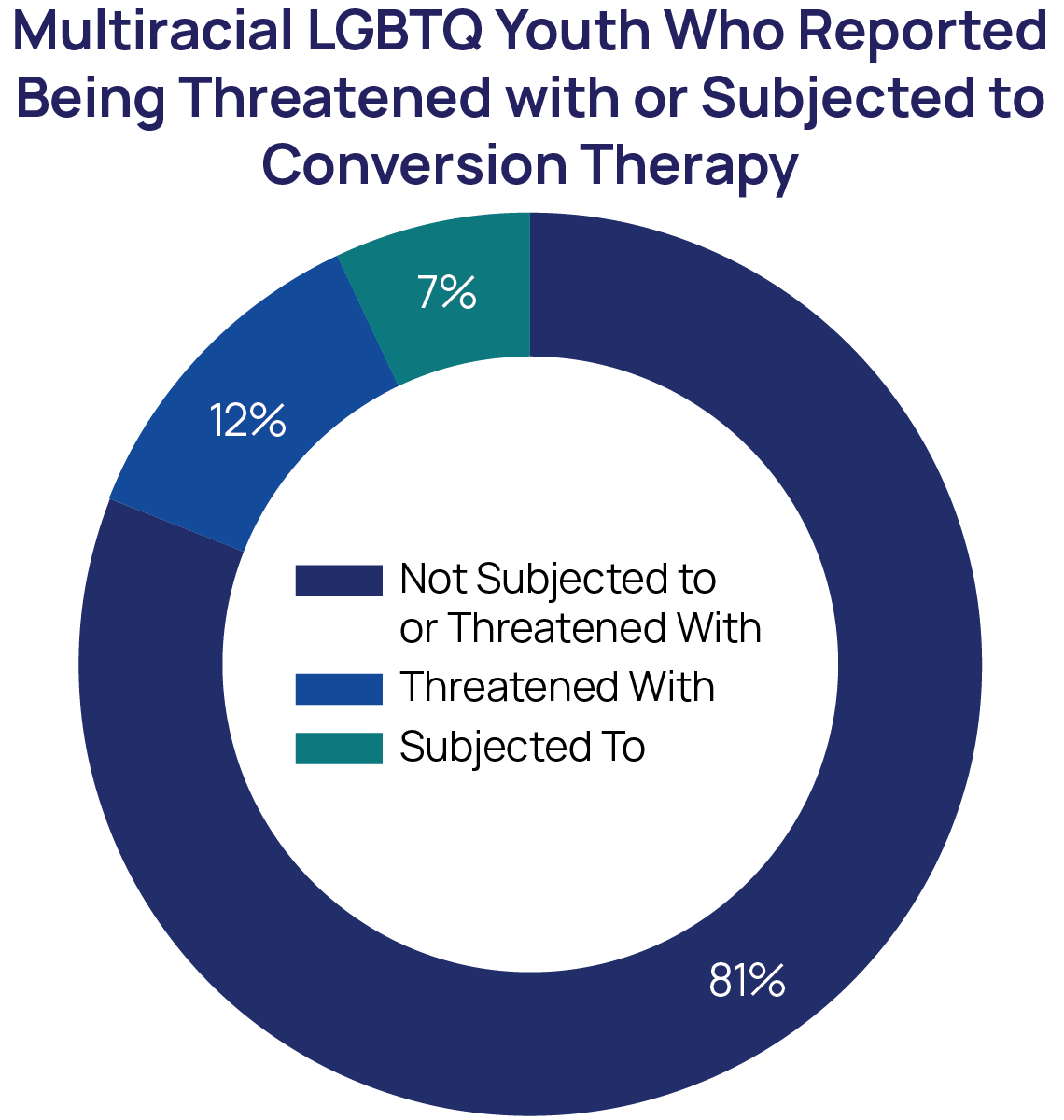

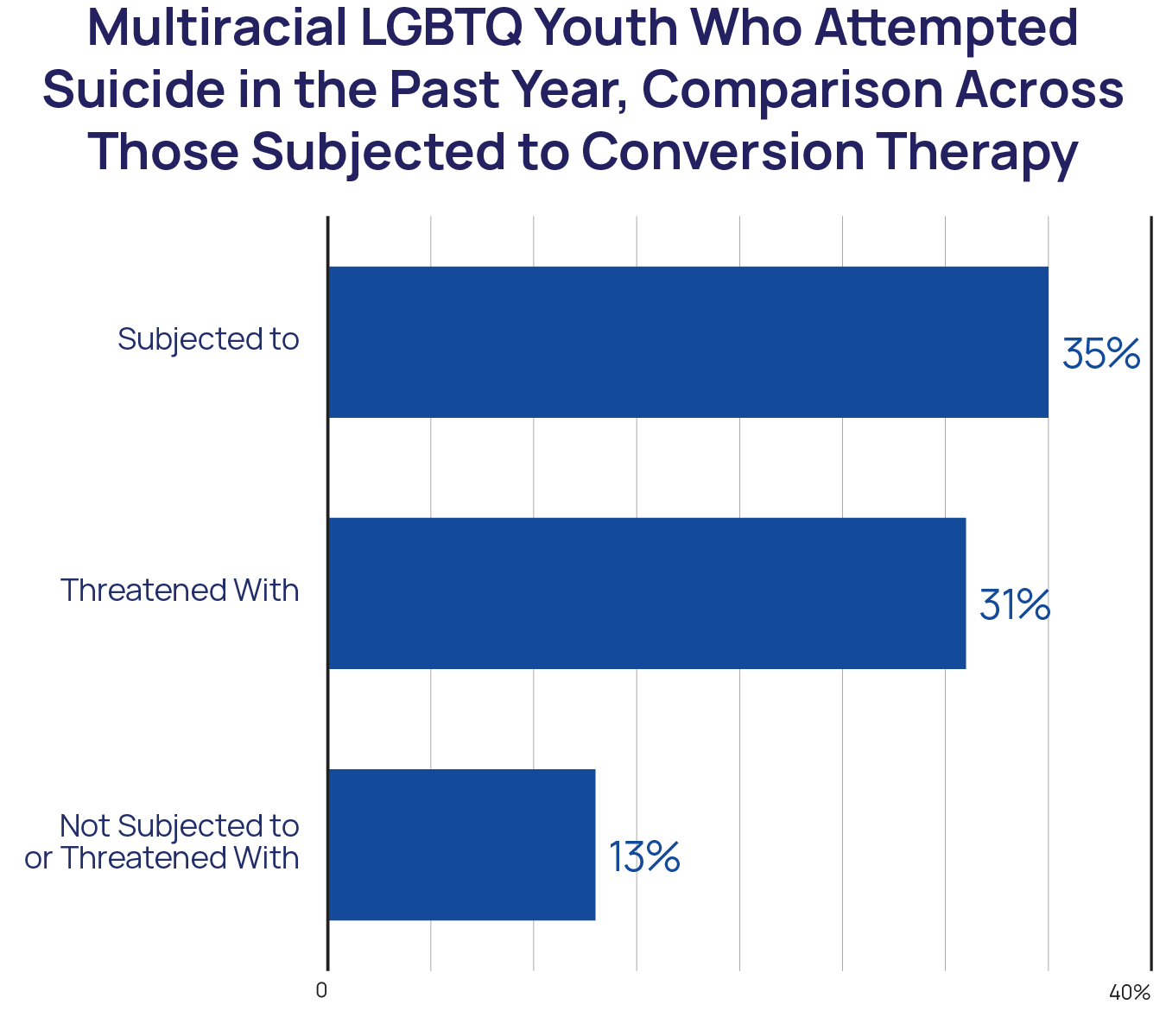

Conversion therapy — attempts by licensed professionals (e.g., psychologists or counselors) or practices by religious leaders to alter sexual attractions and behaviors, gender expression, or gender identity — is still occurring despite a lack of evidence to support this practice and, conversely, mounting evidence illustrating associated harm (Green et al., 2020). Seven percent (7%) of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported having been exposed to conversion therapy, compared to 6% of the full sample of LGBTQ youth. An additional 12% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported having been threatened with conversion therapy, compared to 11% of the full sample. Within multiracial LGBTQ youth, rates of having been exposed to conversion therapy were higher among multiracial LGBTQ youth ages 18–24 and those who were transgender or nonbinary (Table 3), however, rates did not differ significantly between multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity and multiracial youth who are exclusively youth of color. Nearly all multiracial LGBTQ youth (94%) who were subjected to conversion therapy reported that it occurred when they were younger than 18. Given that this is a form of rejection for youth, multiracial LGBTQ youth who were subjected to conversion therapy had three times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 3.16) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who were not. It’s also important to note that even multiracial LGBTQ youth who were threatened with conversion therapy reported higher rates of suicide attempts in the past year (31%) compared to youth who had never been threatened with nor undergone conversion therapy (13%).

Broader than conversion therapy, though certainly inclusive of it, are any attempts by someone to convince a young person to change their sexual orientation and gender identity. Despite what those who are doing this to youth may feel or their motivation for doing so, attempting to convince youth to change who they are is incredibly unsupportive and carries a potential for mental health risks. Nearly two out of three multiracial LGBTQ youth (65%) reported that someone attempted to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity, compared to 61% of monoracial LGBTQ youth. The majority of these attempts came from parents (39%) and non-LGBTQ friends (30%). While the rate for change attempts by a parent or caregiver was similar to what is reported by the full sample of LGBTQ youth (38%), multiracial LGBTQ youth experienced higher rates of change attempts from non-LGBTQ friends compared to the full sample (27%). Multiracial LGBTQ youth who reported that someone tried to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity reported nearly three times the rate of suicide attempts (22%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who did not report that this happened (8%).

Housing Instability and Food Insecurity

Economic stability is one of the five social determinants of health outlined by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) (ODPHP, 2020) and includes both housing stability and food security, illustrating the critical impact that they have on overall well-being. Among multiracial LGBTQ youth, 31% experienced homelessness, had been kicked out, or had run away compared to 23% of monoracial LGBTQ youth. Similar to other findings, multiracial youth who were transgender or nonbinary reported higher rates compared to those who were cisgender (Table 3a, page 31), as did those who were multiracial youth of color compared to multiracial youth who are White and another race/ethnicity. Contrary to other findings, multiracial youth aged 18–24, whose parents have fewer legal consequences for kicking them out, reported higher rates of housing instability. Furthermore, 27% of LGBTQ youth who had experienced housing instability reported a suicide attempt in the past year compared to 13% who did not.

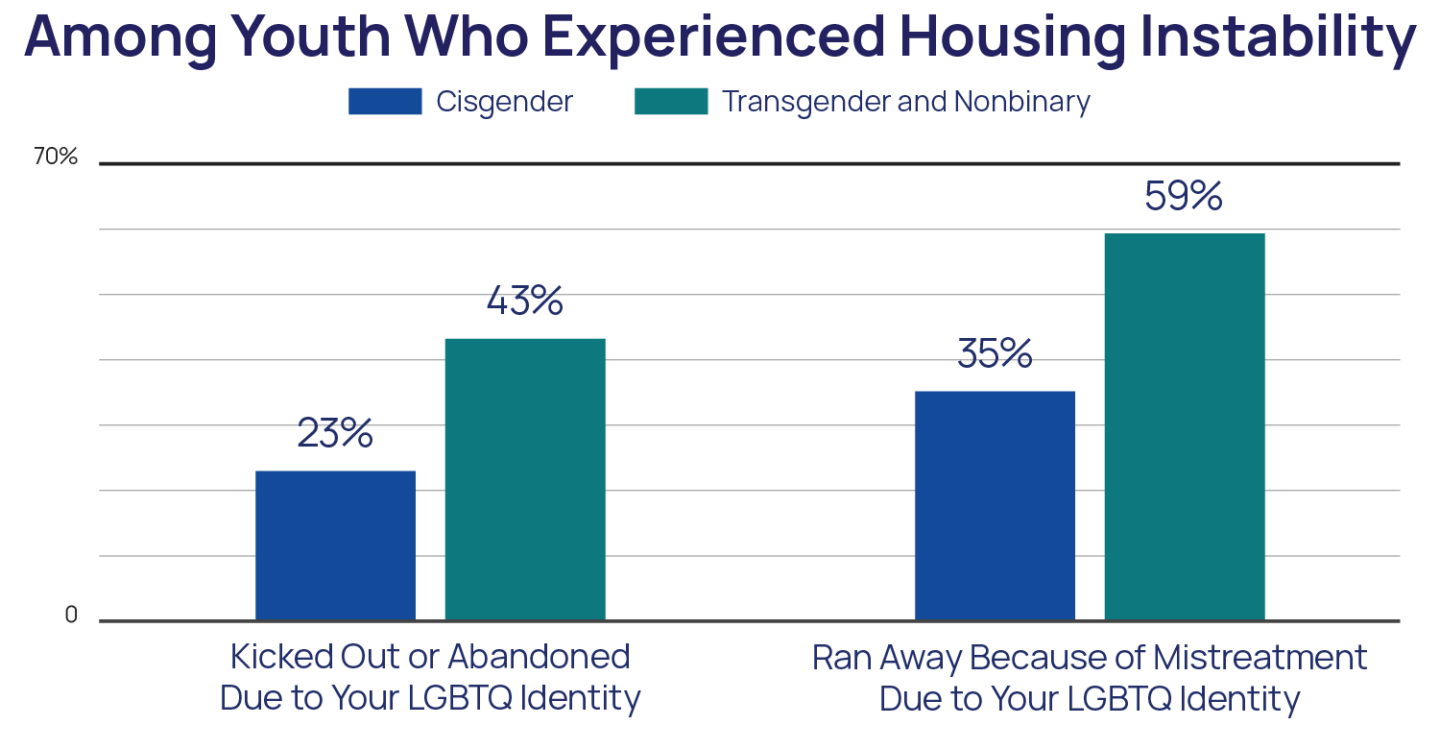

Youth who reported being kicked out or that they ran away were asked a follow-up question about whether it was due to their LGBTQ identity. Among youth who were kicked out, 37% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported having been kicked out or abandoned due to their LGBTQ identity, compared to 42% of the overall sample. Additionally, among youth who ran away, 52% of multiracial LGBTQ reported they ran away because of mistreatment due to their LGBTQ identity, compared to 55% among the full sample of LGBTQ youth. Having been kicked out or abandoned or run away due to their LGBTQ identity were both reported more frequently among multiracial transgender and nonbinary youth (Table 3a).

An important, but often overlooked, aspect of housing instability is youth involvement in foster care. Overall, 7% of multiracial LGBTQ youth had ever been in foster care, which was significantly higher than the rate of monoracial LGBTQ youth involvement in foster care (4%). Nearly one in three multiracial LGBTQ youth who were ever involved in foster care reported a suicide attempt in the past month (32%), compared to 16% of multiracial who were never involved in foster care.

Food insecurity, which is defined as the disruption of food intake or eating patterns because of a lack of money and other resources (Yousefi-Rizi et al., 2021), was reported by 31% of multiracial LGBTQ youth. While this rate was already higher than that reported by monoracial LGBTQ youth (27%), rates of food insecurity were even higher among multiracial transgender and nonbinary youth (37%) and multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color (37%), compared to cisgender (23%) and multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity (30%). This further illustrates the nuances of structural barriers and systemic oppression even among multiracial youth.

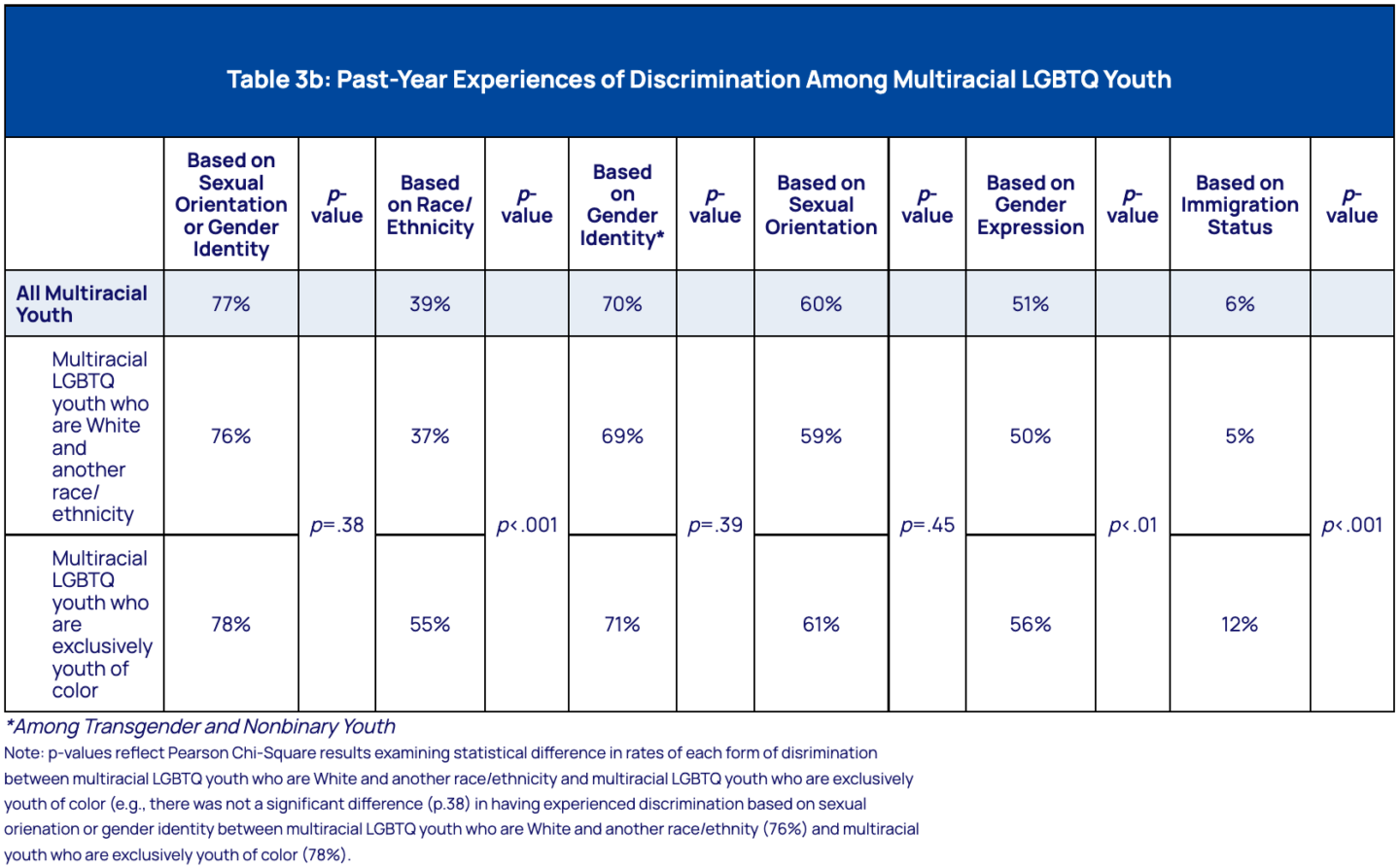

Discrimination Based on Multiple Identities

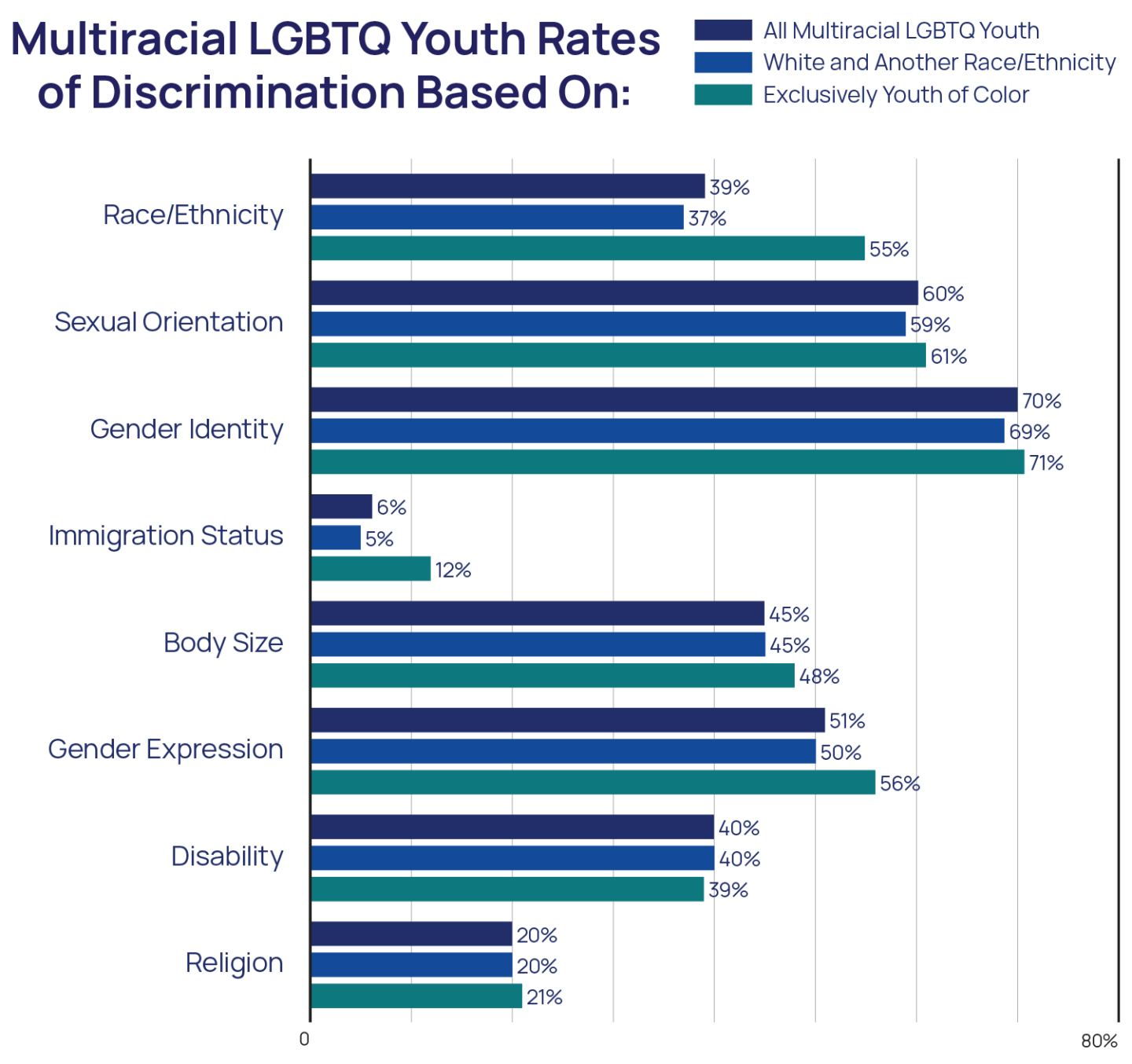

Due to holding many marginalized identities, multiracial LGBTQ youth are susceptible to experiencing discrimination and victimization based on several identities including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual identity, and immigration status. All youth in our sample were asked if they had ever experienced discrimination based on their actual or perceived status in several different identities. In our sample of multiracial LGBTQ youth, 39% reported discrimination based on their race/ethnicity in the past year. This compares to 23% of the full sample of LGBTQ youth and 47% of monoracial LGBTQ youth of color. Three out of five (60%) multiracial LGBTQ youth reported discrimination based on their sexual orientation in the past year. Additionally, half of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported discrimination based on their gender expression (51%), and 70% of multiracial transgender and nonbinary youth reported past-year discrimination based on their gender identity. Finally, 6% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported having been discriminated against based on their immigration status. All of these rates of discrimination were higher than those reported by the overall LGBTQ youth sample.

There were also important differences among multiracial LGBTQ youth (Table 3b, page 32). Multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color reported higher rates of race/ethnicity-based discrimination (55%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity (37%). Multiracial youth who are exclusively youth of color also reported higher rates of discrimination based on their gender expression (56%) and immigration status (12%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity.

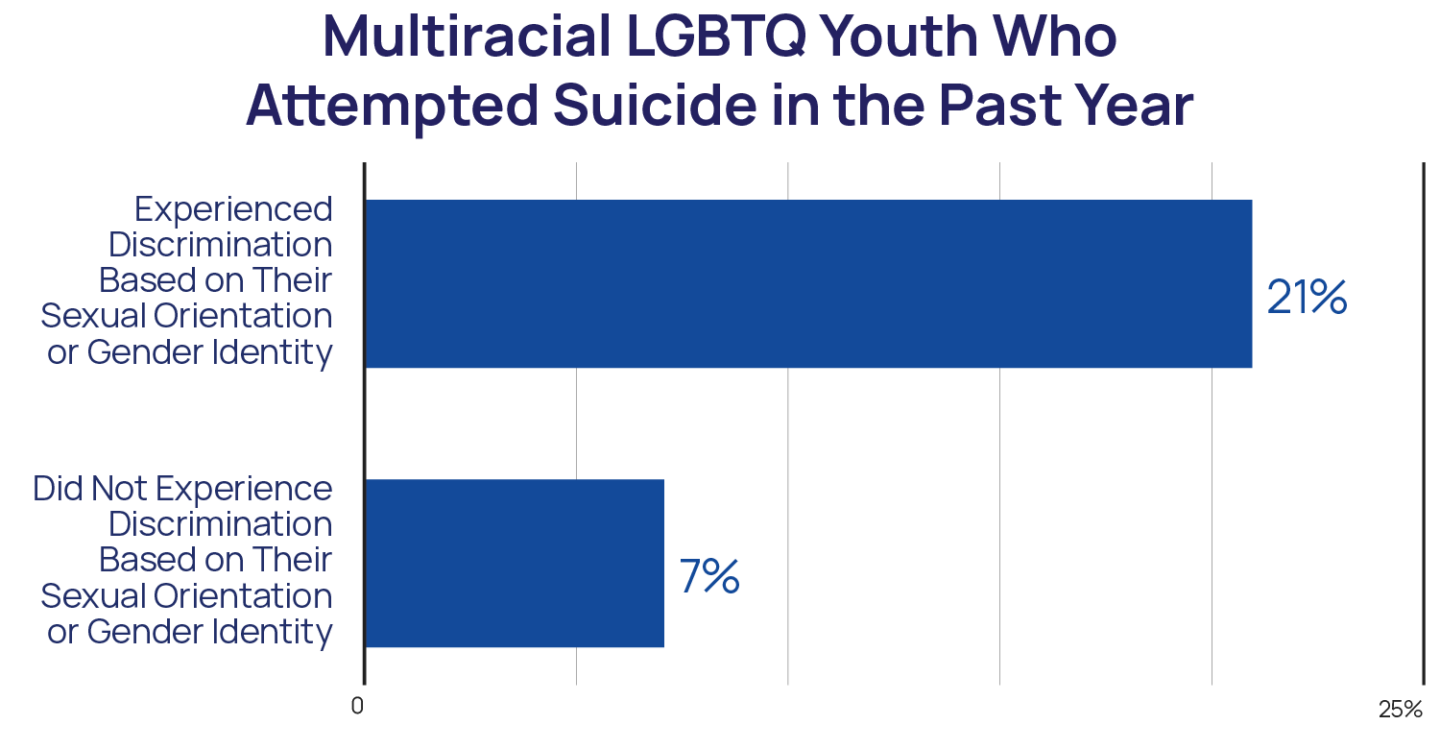

Given our sample of LGBTQ youth, we further explored the impact of discrimination based on either one’s sexual orientation or gender identity. The majority of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year (77%) as did 73% of the full sample of LGBTQ youth. Multiracial LGBTQ youth who experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity reported three times the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (21%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who did not (7%).

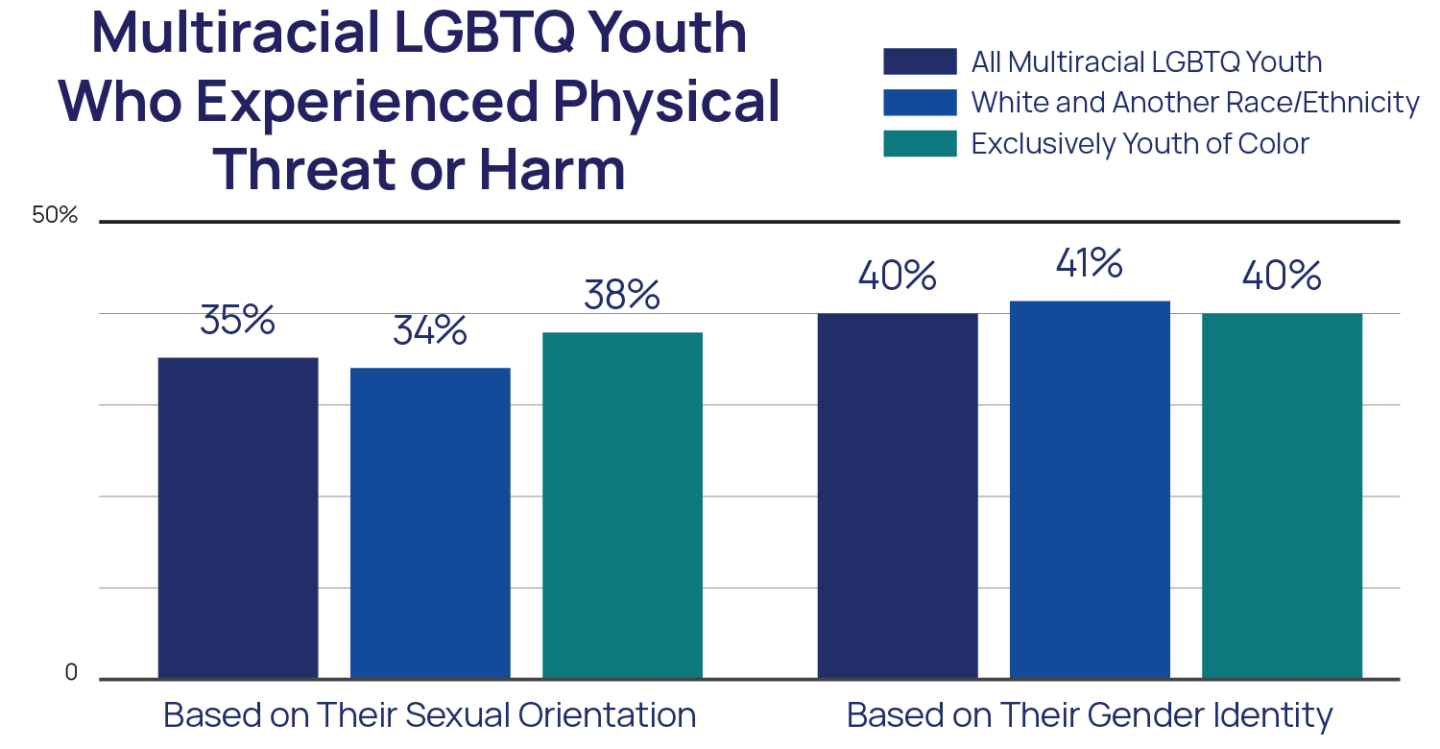

Victimization Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Overall, 40% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported having been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year, a higher rate compared to that of the full LGBTQ youth sample (36%). This includes 40% of multiracial transgender and nonbinary youth who were physically threatened or harmed based on their gender identity, and 35% of multiracial LGBTQ youth who were physically threatened or harmed based on their sexual orientation. Multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color reported higher rates of having been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation (38%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity (34%). More comparisons among multiracial LGBTQ youth can be seen in Table 3b.

Multiracial LGBTQ youth who had been physically threatened or harmed based on their sexual orientation or gender identity reported nearly three times the rate of past-year suicide attempts (28%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who had not (10%).

Suicide Protective Factors for Multiracial LGBTQ Youth

Supportive People

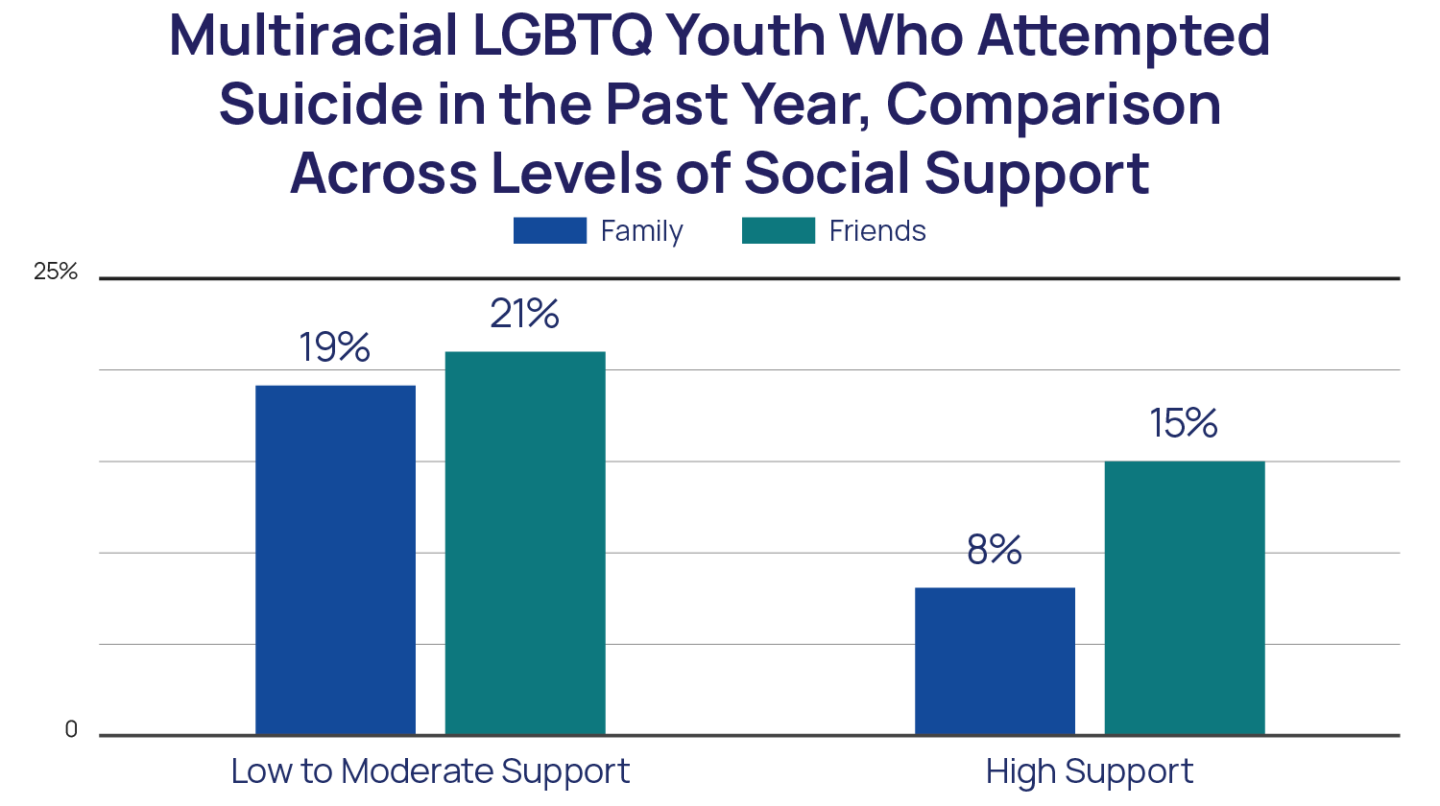

Having supportive people in their lives was protective for multiracial LGBTQ youth. Social support could be viewed as feeling like one’s family members and friends are there for them when needed or trying to help them when they have troubles. Multiracial LGBTQ youth who reported high levels of family social support had 55% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = .45) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who did not have high family social support. Moreover, multiracial LGBTQ youth who reported high levels of social support from friends had 39% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = .61) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who did not have high social support from friends.

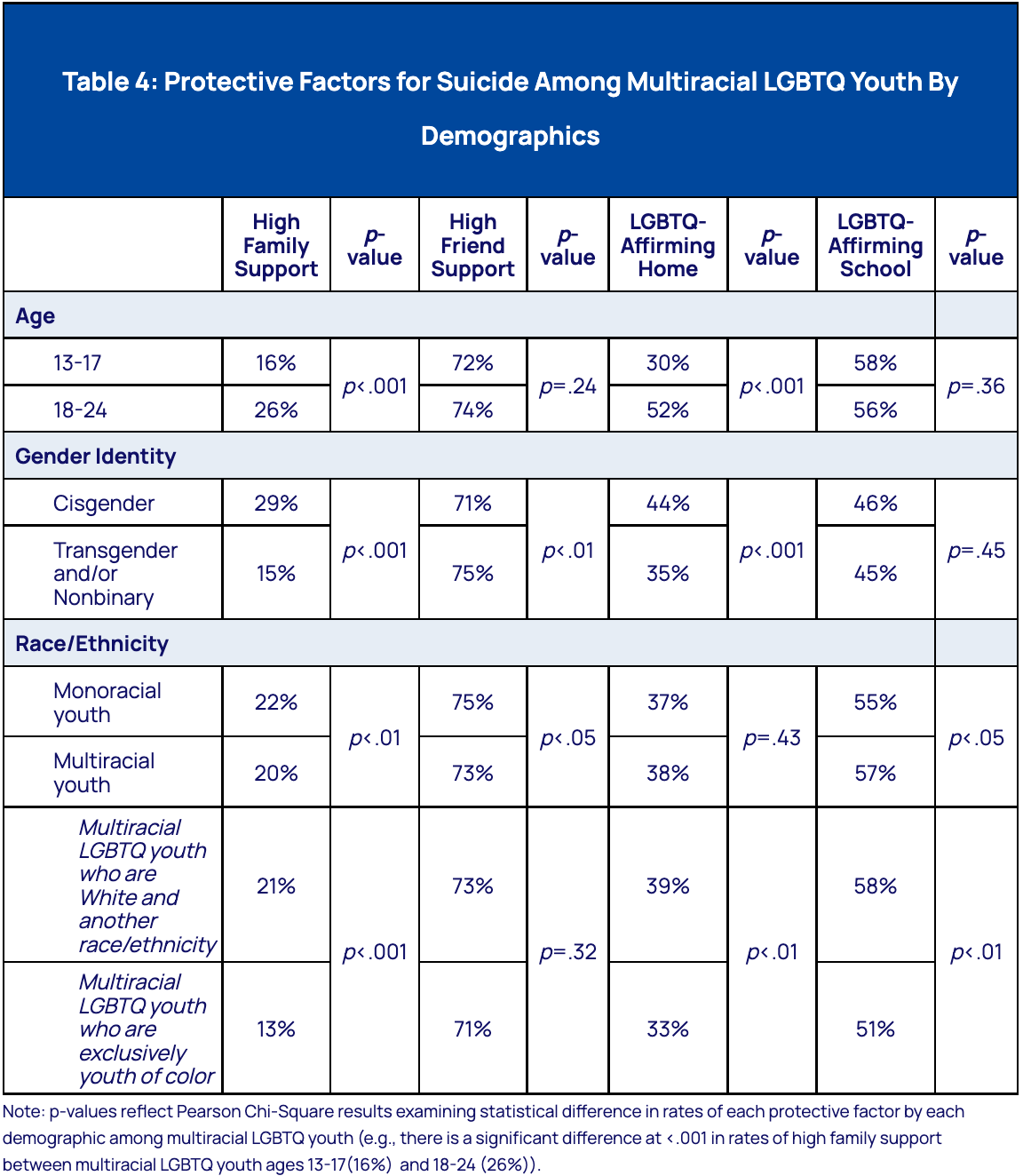

That said, only one in five multiracial LGBTQ youth (20%) reported having high levels of social support from family, which is lower than that of the monoracial LGBTQ sample (22%, Table 4). Even fewer multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color (13%), multiracial LGBTQ youth ages 13–17 (16%), and transgender and nonbinary multiracial youth (15%), reported high levels of family social support. While high social support from friends was more frequently reported among multiracial LGBTQ youth (73%) compared to high family support, this was still at a lower rate than that reported by monoracial LGBTQ youth (75%). The only difference in social support from friends among multiracial LGBTQ youth was that it was higher among transgender and nonbinary multiracial youth (75%) compared to cisgender multiracial youth (71%).

Affirming Spaces

Being able to be in spaces that affirm their LGBTQ identity was also associated with lower rates of suicide attempts for multiracial LGBTQ youth. Overall, 57% of multiracial LGBTQ youth reported their school was LGBTQ-affirming, including 56% of multiracial LGBTQ youth ages 18-24 and 58% of multiracial LGBTQ youth ages 13–17. This rate was higher than what was reported by monoracial LGBTQ youth (55%).

Multiracial LGBTQ youth who attended LGBTQ-affirming schools reported lower rates of suicide attempts in the past year (15%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who did not attend LGBTQ-affirming schools (21%), with the overall finding that multiracial youth attending LGBTQ-affirming schools had a 33% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR =.67) compared to multiracial LGBTQ who were not at LGBTQ-affirming schools.

Multiracial LGBTQ youth who were in LGBTQ-affirming homes also reported a lower rate of suicide attempts in the past year (12%) compared to those whose homes were not LGBTQ-affirming (19%). That said, only 38% of multiracial LGBTQ youth lived in an LGBTQ-affirming home. Additionally, rates differed among multiracial youth, with less than one-third of younger multiracial youth (aged 13–17) who reported their home was LGBTQ-affirming (30%), and one-third of multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color (33%). Overall, more multiracial LGBTQ youth reported that their schools were LGBTQ-affirming compared to having LGBTQ-affirming homes, suggesting schools play an important role in providing needed LGBTQ identity affirmation and support.

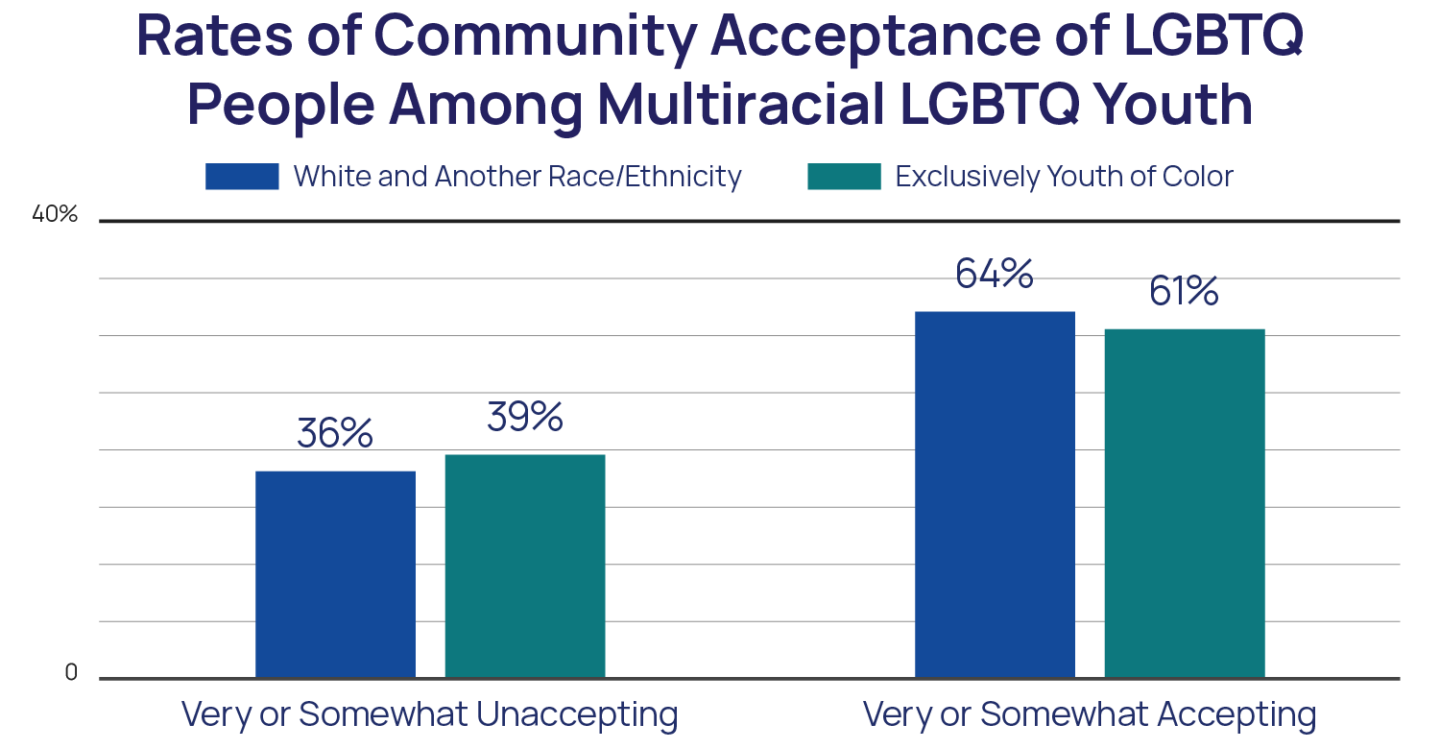

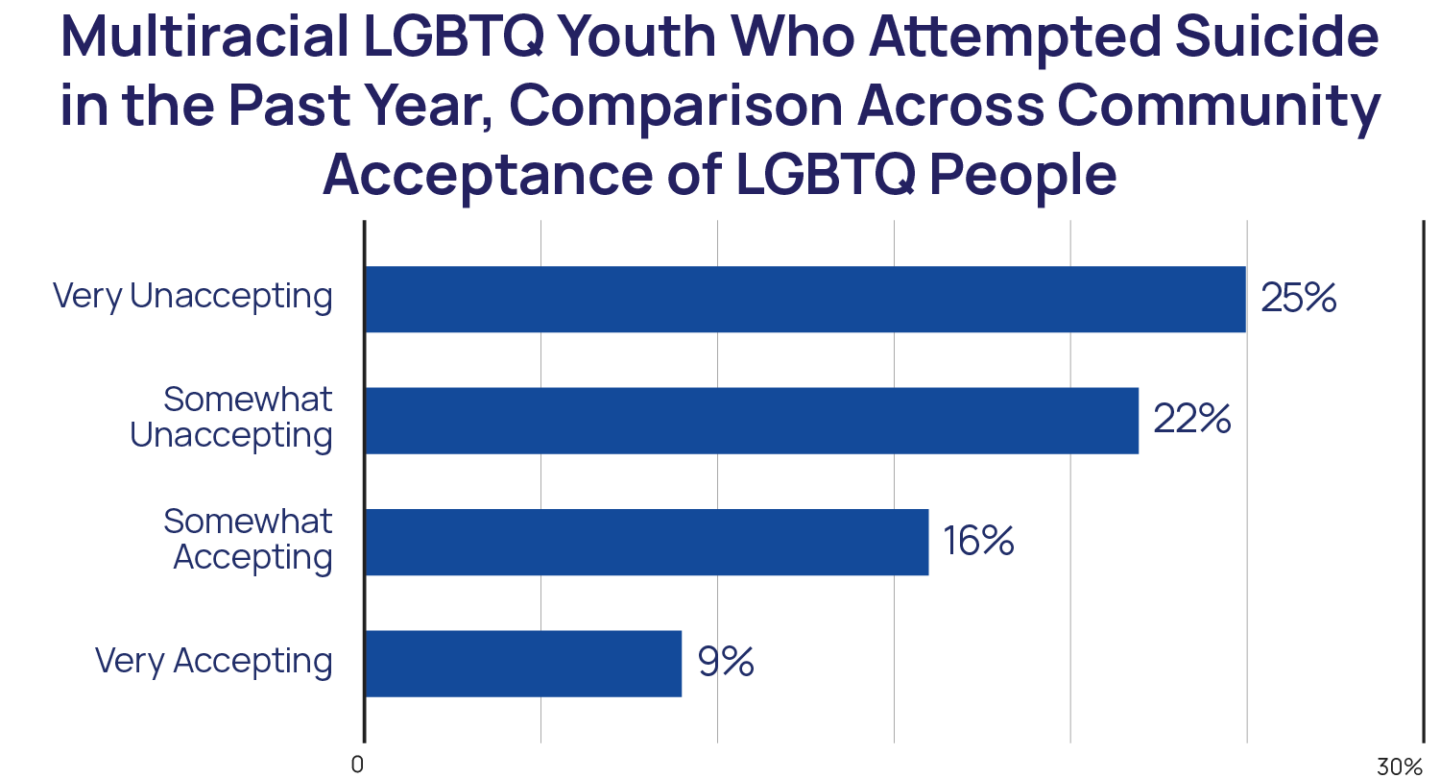

While LGBTQ youth may find themselves in supportive homes and schools, overall community-level support can also impact their well-being in terms of how they and their family are treated outside of those environments, and what policies may be enacted. Indeed, multiracial LGBTQ youth who currently lived in communities that were very accepting of LGBTQ people reported lower rates of suicide attempts in the past year (9%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who currently lived in very unaccepting communities (25%). While 64% of multiracial reported living in communities there were either very or somewhat accepting of LGBTQ people, of importance, multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity reported higher rates of living in very or somewhat accepting communities (64%) compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color (61%).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Multiracial LGBTQ youth have a diversity of identities and experiences that should be acknowledged and validated. The current findings show that multiracial LGBTQ youth represent a diverse group of youth in their racial, sexual, and gender identities, as well as their experiences. Three out of four multiracial LGBTQ youth identified with two races/ethnicities and 25% with more than two, covering a vast array of racial, ethnic, immigrant, and linguistic experiences. Additionally, while multiracial LGBTQ youth’s sexual identities mirrored those of the overall LGBTQ sample, more multiracial LGBTQ youth identified as transgender or nonbinary and used pronouns that fell outside of the binary construction of gender. It is possible that multiracial youth who are already navigating the complexities of racial identity are more comfortable embracing more nuanced gender and sexual identities. Overall, these findings underscore the importance of purposefully validating multiracial LGBTQ youth’s intersection of racial/ethnic identities and LGBTQ identities in both data collection and youth-serving organizations. This specifically means assessing multiracial identities in such a way that allows youth to respond that they have more than race/ethnicity, to be able to specify what those races/ethnicities are, and to leave multiracial as a racial/ethnic group in and of itself. Furthermore, creating affirming environments for multiracial youth also includes interpersonal interactions and proper training and education that address microaggressions specific to multiracial people and how to address them when youth may do them to one another. Finally, LGBTQ-serving organizations must acknowledge that all LGBTQ youth’s experiences are not the same, and there is value in understanding how to improve the well-being of all LGBTQ youth.

The issues faced by multiracial LGBTQ youth are stark and demand attention from stakeholders. Multiracial LGBTQ youth report higher rates of symptoms of anxiety, symptoms of depression, and self-harm compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth. Multiracial LGBTQ youth also report 10% higher rates of considering suicide and nearly 30% higher rates of suicide attempts in the past year compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth. Additionally, multiracial LGBTQ youth are exposed to increased rates of risk factors for suicide such as discrimination, housing instability, food insecurity, and having been threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity when compared to our overall sample of LGBTQ youth. These findings overwhelmingly support greater investment in multiracial LGBTQ youth’s mental health through increased access to treatment and prevention programs that specifically affirm their racial identity and the nuances of navigating the world as a multiracial person.

The experiences of multiracial LGBTQ youth are not monolithic and differences within the experiences of multiracial individuals should be taken into consideration when addressing multiracial LGBTQ youth’s mental health. Multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity reported better mental health and well-being and fewer risks compared to multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color. Despite these findings, multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color reported lower access to the mental health care they wanted. These findings suggest that, as other researchers have also hypothesized, multiracial LGBTQ youth who are perceived by others as people of color may also be subjected to the same stigma and oppression as monoracial LGBTQ youth of color, whereas multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race may have access to White privilege. While it is unclear if youth in our sample are being perceived by others as White or not, what is clear is that our findings point to the need to examine within-group differences among multiracial LGBTQ whenever possible. These findings also suggest that mental health interventions may need to be specifically targeted to address the needs of multicultural youth who are exclusively youth of color and the unique risk factors they may face, such as higher rates of racial discrimination, when considering how to ensure that they are salient for multiracial LGBTQ youth. Examining and dismantling systemic racism in our mental healthcare system (e.g., recruiting and retaining mental health practitioners from diverse and multiracial backgrounds), would also potentially address the disparities observed between multiracial LGBTQ youth who are White and another race/ethnicity and multiracial LGBTQ youth who are exclusively youth of color.

The research community has failed to acknowledge the disparities of multiracial LGBTQ youth compared to monoracial LGBTQ youth. Researchers have historically failed to examine multiracial youth’s developmental outcomes as well as those of LGBTQ youth, leaving outcomes specific to multiracial LGBTQ youth at the intersection of these two identities starkly underreported. With multiracial LGBTQ results being left out of life-saving research, important resources are unable to be properly allocated to those most in need. With multicultural youth being one of the fastest-growing racial/ethnic identities in the U.S., the lack of available sample size is no longer a valid excuse for researchers to fail to separately report findings on multiracial LGBTQ youth. Researchers must make an effort to properly assess multiracial identities in order to facilitate proper data collection and analysis.

The Trevor Project is committed to working toward improving and supporting the mental health and well-being of multiracial LGBTQ youth. Our crisis services are committed to ensuring that all LGBTQ youth, including those who are multiracial, are provided high-quality, culturally-validating care, and we have worked to create a team of diverse counselors that aligns with the demographics of the youth we serve. Our research team continues to be committed to the ongoing dissemination of findings specific to multiracial LGBTQ youth to support The Trevor Project’s work to support all LGBTQ youth, as well as external partners and stakeholders’ desire to better understand and address the needs of multiracial LGBTQ youth.

| The authors of this report acknowledge and extend our deepest gratitude to our Research Associate, Hannah R. Rosen, for providing assistance and feedback on the creation of this report. |

About The Trevor Project

The Trevor Project is the world’s largest suicide prevention and mental health organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, & questioning (LGBTQ) young people. The Trevor Project offers a suite of 24/7 crisis intervention and suicide prevention programs, including TrevorLifeline, TrevorText, and TrevorChat as well as the world’s largest safe space social networking site for LGBTQ youth, TrevorSpace. Trevor also operates an education program with resources for youth-serving adults and organizations, an advocacy department fighting for pro-LGBTQ legislation and against anti-LGBTQ policies, and a research team to examine the most effective means to help young LGBTQ people in crisis and end suicide. If you or someone you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386, via chat TheTrevorProject.org/Help, or by texting START to 678-678.

This report is a collaborative effort from the following individuals at The Trevor Project:

Myeshia N. Price, PhD

Senior Research Scientist

Jonah P. DeChants, PhD

Research Scientist

Carrie K. Davis, MSW

Chief Community Officer

Recommended Citation: Price, M. N., DeChants, J. P., & Davis, C. K. (2022).The mental health and well-being of multiracial LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

Media inquiries:

Research inquiries:

REFERENCES

- Baams, L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038994

- Banks, B. M., Cicciarelli, K. S., & Pavon, J. (2022). It offends us too! An exploratory analysis of high school-based microaggressions. Contemporary School Psychology, 26(18), 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-020-00300-1

- Blacksher, E., & Valles, S. A. (2021). White privilege, white poverty: Reckoning with class and race in America. Hastings Center Report, 51(S1), S51–S57. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1230

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Elkhadem, A. J., & Smith, R. A. (2016). Multiracial persons and LGBT status (Issue Brief). https://doi.org/10.7916/D8571CG6

- Felipe, L. C., Garrett-Walker, J. J., & Montagno, M. (2022). Monoracial and multiracial LGBTQ+ people: Comparing internalized heterosexism, perceptions of racism, and connection to LGBTQ+ communities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(1), 1–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000440

- Franco, M. G., & O’Brien, K. M. (2018). Racial identity invalidation with multiracial individuals: An instrument development study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(1), 112–125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000170

- Green, A. E., Price-Feeney, M., Dorison, S. H., & Pick, C. J. (2020). Self-reported conversion efforts and suicidality among US LGBTQ youths and young adults, 2018. American Journal of Public Health, 110(8), 1221–1227. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305701

- Herman, M. (2004). Forced to choose: Some determinants of racial identification in multiracial adolescents. Child Development, 75(3), 730–748.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00703.x

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Underwood, J. M.(2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students — 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27.http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

- Jones, N., Marks, R., Ramirez, R., & Ríos-Vargas, M. (2021, August 12). 2020 census illuminates racial and ethnic composition of the country. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html

- Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Zongrone, A. D., Clark, C. M., & Truong, N. L. (2018). The 2017 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/GLSEN-2017-National-School-Climate-Survey-NSCS-Full-Report.pdf

- Ladson-Billings, G., & Tate IV, W. F. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record, 97(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146819509700104

- Lytle, M. C., De Luca, S. M., & Blosnich, J. R. (2014). The influence of intersecting identities on self‐harm, suicidal behaviors, and depression among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 44(4), 384-391. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12083

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Navarrete, V., & Jenkins, S. R. (2011). Cultural homelessness, multiminority status, ethnic identity development and self-esteem. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 791–804. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.04.006

- Nishina, A., & Witkow, M. R. (2020). Why developmental researchers should care about biracial, multiracial, and multiethnic youth. Child Development Perspectives, 14(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12350

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Social determinants of health. Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

- Price, M. N., Green, A. E, & Davis, C. (2021). Multisexual youth mental health: Risk and protective factors for youth who are attracted to more than one gender. The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/multisexual-youth-mental-health risk-and-protective-factors-for-bisexual-pansexual-and-queer-youth-who-are-attrcted-to-more-than-one-gender/

- Price-Feeney, M., Green, A. E., & Dorison, S. (2020). Understanding the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), 684–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.11.314

- Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 126(6), 1117–1123. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0852

- Rockquemore, K. A., Brunsma, D. L., & Delgado, D. J. (2009). Racing to theory or retheorizing race? Understanding the struggle to build a Multi-racial identity theory. Journal of Social Issues, 65(1), 13–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.01585.x

- Samuels, G. M. (2014). Multiethnic and multiracialism. In Encyclopedia of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.991

- Shih, M., & Sanchez, D. T. (2005). Perspectives and research on the positive and negative implications of having multiple racial identities. Psychological Bulletin, 131(4), 569–591. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.569

- Truong, N. L., Zongrone, A. D., & Kosciw, J. G. (2020). Erasure and resilience: The experiences of LGBTQ students of color, Asian American and Pacific Islander LGBTQ youth in U.S. schools. GLSEN. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED603844.pdf

- Yousefi-Rizi, L., Baek, J. D., Blumenfeld, N., & Stoskopf, C. (2021). Impact of housing instability and social risk factors on food insecurity among vulnerable residents in San Diego County. Journal of Community Health, 46, 1107–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-00999-w Zongrone, A. D., Truong, N. L., & Kosciw, J. G. (2020). Erasure and resilience: The experiences of LGBTQ students of color, Native American, American Indian, and Alaska Native LGBTQ youth in U.S. schools. GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/Erasure-and-Resilience-Native-2020.pdf