Background

Schools and the professionals who work within them play key roles in the lives of LGBTQ young people. Teachers, professors, and school counselors are important sources of information, support, and care for LGBTQ students, especially in the absence of support from their families or local communities. LGBTQ students who identified a greater number of supportive school staff reported higher levels of self-esteem, lower levels of depression, and lower rates of having seriously considered suicide in the past year (Kosciw et al., 2022). Among LGBQ students, having caring teachers is associated with lower levels of negative mental health symptoms (Parmar et al., 2022). Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People, this brief examines the relationships between caring teachers and student mental health, including transgender and nonbinary students, as well as demographic differences in LGBTQ young people’s access to caring relationships in schools. This brief additionally investigates rates of LGBTQ young people who report learning about LGBTQ topics from school staff and associations between learning about LGBTQ topics and mental health.

Results

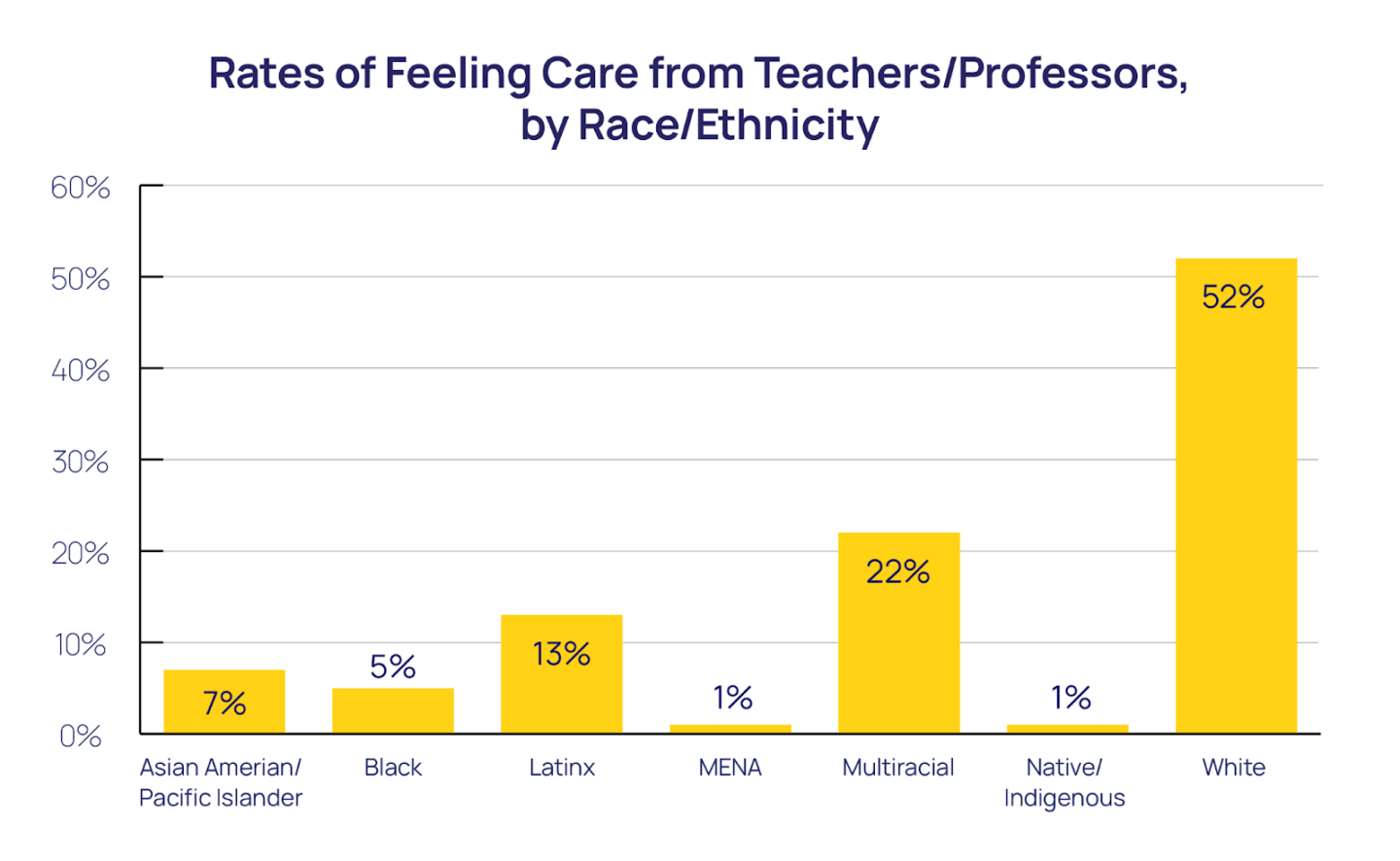

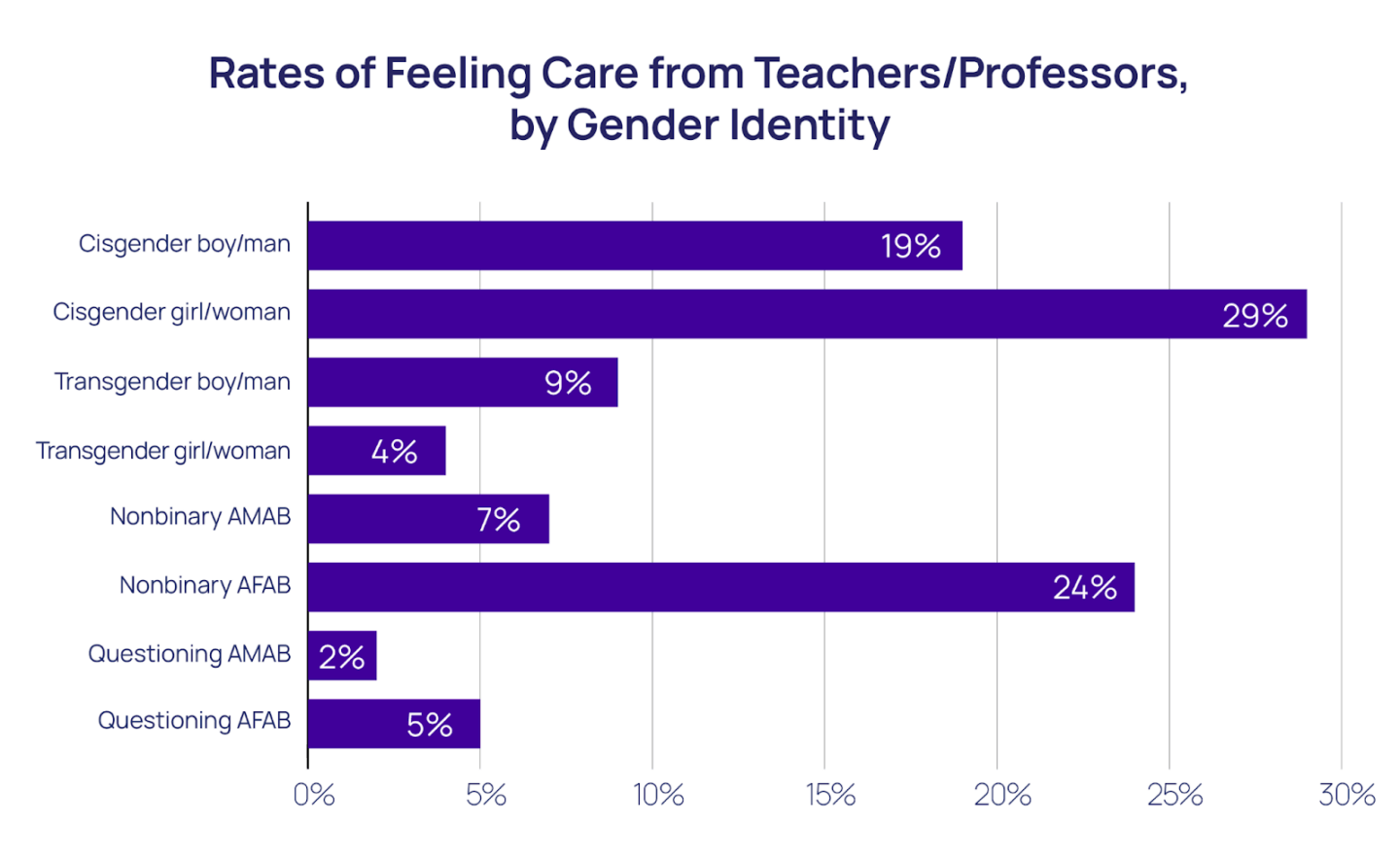

Young LGBTQ people of color, transgender and nonbinary young people, and young people from lower socioeconomic status all reported lower rates of feeling their teacher or professor cared about them. LGBTQ young people of color reported lower rates of feeling that their teachers or professors cared a lot or very much about them, compared to their White LGBTQ peers. Across gender identity, transgender and nonbinary young people reported lower rates of feeling that their teachers or professors cared a lot or very much about them compared to their cisgender peers. LGBTQ young people who were assigned female at birth reported higher rates of feeling that their teachers or professors cared a lot or very much about them compared to their peers who were assigned male at birth. One in 5 cisgender girls and women (20%) reported feeling that their teachers or professors cared a lot or very much about them, compared to 17% of cisgender boys and men. Meanwhile, nearly one in ten (9%) transgender boys and men and nearly one in four (24%) of nonbinary young people assigned female at birth reported that they felt that their teachers or professors cared a lot or very much about them, compared to 4% of transgender girls and women and 7% of nonbinary young people assigned male at birth. Among LGBTQ young people who reported just meeting their basic financial needs, only 12% reported feeling that their teachers or professors cared a lot or very much about them, compared to 88% of LGBTQ young people who reported more than just meeting their basic needs.

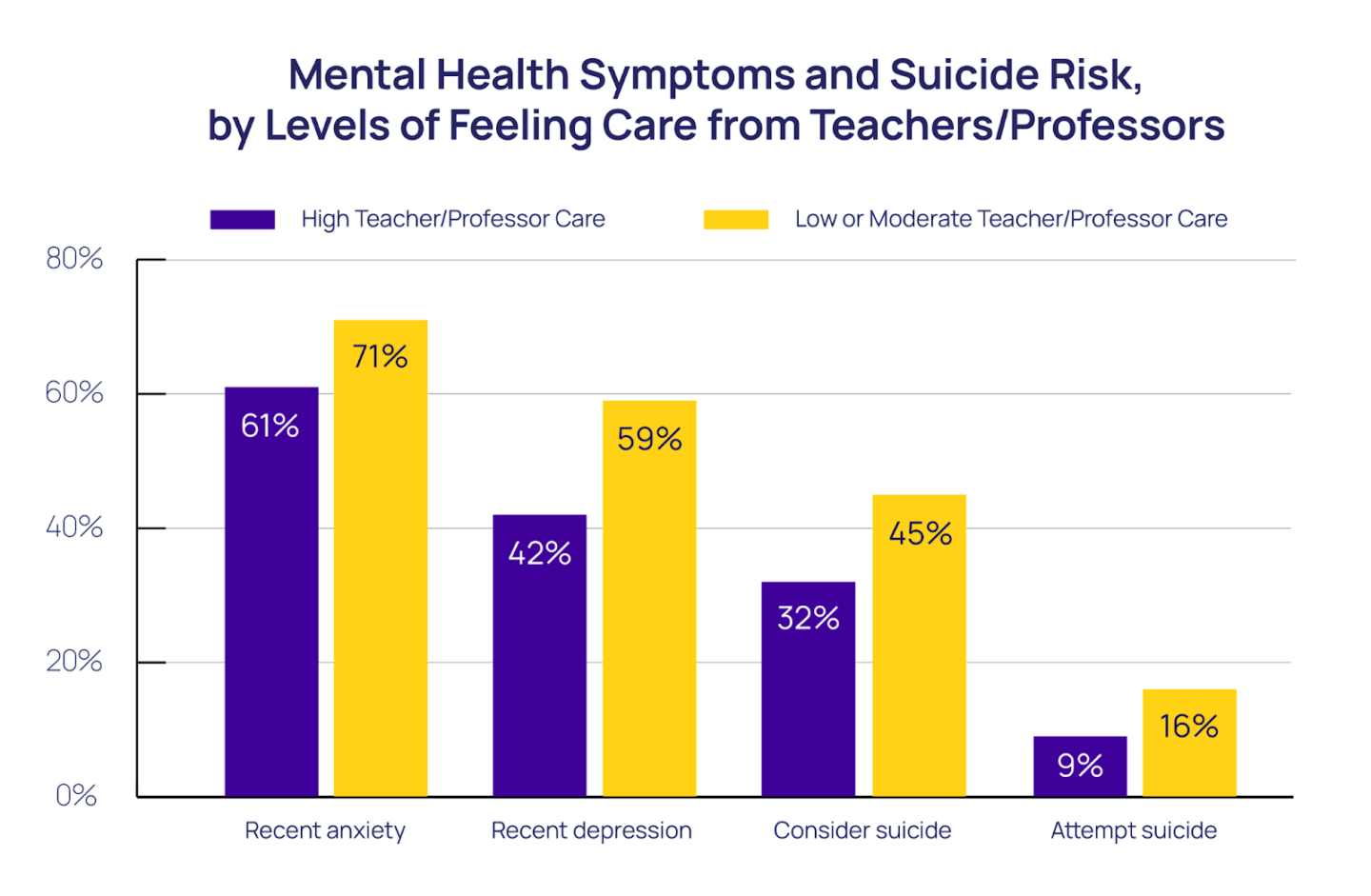

Feeling that their teachers or professors cared a lot or very much about them was associated with 34% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year for LGBTQ young people (aOR = 0.66 [CI = 0.59-0.75], p<0.001). LGBTQ young people who reported that they felt that their teachers or professors cared a lot or very much about them also reported 32% lower odds of recent anxiety (aOR = 0.68 [CI = 0.63-0.73], p<0.001), 43% lower odds of recent depression (aOR = 0.57 [CI = 0.53-0.61], p<0.001), and 37% lower odds of seriously considering suicide in the past year (aOR = 0.63 [CI = 0.59-0.68], p<0.001).

Learning about LGBTQ identities and related topics from teachers and professors was associated with lower odds of recent depression among LGBTQ students. Some LGBTQ young people in our sample reported that teachers and school counselors are their sources of information about LGBTQ identities (7%), issues impacting the LGBTQ community (6%), and politics related to LGBTQ people (18%). LGBTQ young people who learned about these topics from teachers or school counselors reported lower rates of recent depression. More specifically, learning about LGBTQ identities from a teacher or school counselor was associated with 15% lower odds of recent symptoms of depression (aOR = 0.85, [CI= 0.77 – 0.95], p<0.01), learning about issues impacting the LGBTQ community was associated with 23% lower odds of recent symptoms of depression (aOR = 0.77, [CI- 0.69 – 0.87], p<0.001), and learning about politics related to LGBTQ people was associated with 17% lower odds of recent symptoms of depression (aOR = 0.83, [CI= 0.74 – 0.94], p<0.01).

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2022 of 28,524 LGBTQ young people recruited via targeted ads on social media. The item assessing teachers’ and professors’ care for students asked respondents, “How much do you feel that your teachers/professors care about you?”. Response options included 1) Not at all, 2) A little, 3) Somewhat, 4) A lot, and 5) Very much. Participants were also asked where they received information about LGBTQ identities, topics or issues impacting the LGBTQ community, and politics related to LGBTQ people, with teacher/counselors at school as one of several response options that respondents could choose from. Recent anxiety was assessed using the GAD-2 (Plummer et al., 2016), and recent depression was assessed using the PHQ-2 (Richardson et al., 2010). Questions assessing suicide risk were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Crosstabs and chi-square analyses were used to examine frequencies and differences in rates among different groups. Adjusted logistic regression models were conducted to determine the association between feeling care from teachers and professors and recent symptoms of anxiety, recent symptoms of depression, seriously considering suicide in the past year, and attempting suicide in the past year, while controlling for age, Census Region, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual identity. All reported comparisons and adjusted odds ratios are statistically significant at least at p<0.05. This means that there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance.

Looking Ahead

Caring teachers and professors can play an important role in supporting the mental health of LGBTQ students. These findings align with previous research which has found that the presence of supportive school staff is associated with lower rates of depression and seriously considering suicide in the past year (Kosciw, 2022,) and further show that feeling care from teachers or professors is associated with lower rates of recent symptoms of anxiety and attempting suicide in the past year.

Not all LGBTQ students have equal access to caring teachers, however. Alarming disparities were observed in our data along the lines of socioeconomic status, race, and gender identity. In our sample, LGBTQ young people who reported just meeting their basic economic needs reported drastically lower rates of feeling care from teachers and professors compared to their LGBTQ peers who more than met their basic economic needs. Additionally, White LGBTQ young people reported more than double the rate of feeling care from teachers and professors than their LGBTQ peers of color. These findings may reflect implicit bias among teachers, who could be conditioned to perceive low-income or BIPOC students as less deserving of or less in need of their care (Ready & Wright, 2011). Given that schools serving low-income and BIPOC students tend to be underfunded in comparison to schools serving predominantly White students or middle- to high-income students (Darling-Hammond, 2004), it is imperative that school districts allocate adequate resources to attract and retain high-quality teachers for schools serving students of all identities and backgrounds. LGBTQ young people who were assigned male at birth also reported lower rates of feeling care from teachers and professors compared to their LGBTQ peers who were assigned female at birth. This may reflect teachers’ implicit biases toward students perceived as male or trans feminine, who may also be perceived as less in need of teachers’ care (Muntoni & Retelsdorf, 2018). Teaching is a challenging profession, made harder in many areas by the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictive laws about topics that can be discussed in the classroom. Decision-makers at local, state, and national levels must ensure that all schools are fully staffed and that staff have the support they need to build caring relationships with all students.

Finally, our findings show that teachers and school counselors are important sources of information about LGBTQ identities, issues, and politics for LGBTQ students. Almost one in five LGBTQ young people reported having learned about policies impacting LGBTQ people from a teacher or school counselor. Learning about LGBTQ identities, issues, or politics from a teacher or school counselor were also associated with lower odds of reporting recent symptoms of depression. Providing information about LGBTQ identities and topics is one way that teachers, professors, and counselors can demonstrate their care and support for LGBTQ young people.

Overall, these findings highlight the need to support educators as allies to LGBTQ young people. This support can take the form of LGBTQ-cultural competency training to help educators feel more comfortable and equipped to discuss LGBTQ issues and support LGBTQ students, as well as broader funding and support to make sure educators have ample time and resources to support all students. Other potentially beneficial policies include zero-tolerance policies around anti-LGBTQ harassment and language in schools, the establishment of gender-neutral bathrooms, and the use of gender-neutral language when addressing students. Teachers can help support LGBTQ students by checking curricula for anti-LGBTQ bias, uplifting LGBTQ key figures from history, and sponsoring or proposing Gender-Sexuality Alliances (GSAs). Other research has found that students at schools which have GSAs report lower likelihood of depressive symptoms and suicidality (Baams & Russell, 2021). While recent legislation has sought to limit teachers’ ability to discuss LGBTQ identities in the classroom, it is imperative that teachers have the freedom to discuss these topics and express their support for LGBTQ young people in their schools.

The Trevor Project is committed to supporting all LGBTQ young people and the adults who serve them. For adults who work with LGBTQ young people and want to learn more about how to support them, we offer multiple resources on our website, including a Guide to Being an Ally to Transgender and Nonbinary Youth and our Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention. Our 24/7 crisis services are available in three different modalities – phone, chat, and text – for young people to connect with affirming counselors when they are in crisis. Our TrevorSpace platform also connects young people with supportive peers. Further, Trevor’s research and advocacy teams are focused on using data to advance LGBTQ-inclusive policies and practices and empower youth-serving professionals with the knowledge necessary to understand and address these young people’s unique mental health needs.

References

- Baams, L., & Russell, S. T. (2021). Gay-straight alliances, school functioning, and mental health: Associations for students of color and LGBTQ Students. Youth & Society, 53(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X20951045

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2004). The color line in American education: Race, resources, and student achievement. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 1(02). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X0404202X

- Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., & Menard, L. (2022). The 2021 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of LGBTQ+ youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN.

- Muntoni, F., & Retelsdorf, J. (2018). Gender-specific teacher expectations in reading—The role of teachers’ gender stereotypes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.06.012

- Parmar, D. D., Tabler, J., Okumura, M. J., & Nagata, J. M. (2022). Investigating protective factors associated with mental health outcomes in sexual minority youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(3), 470–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.004

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31.

- Ready, D. D., & Wright, D. L. (2011). Accuracy and inaccuracy in teachers’ perceptions of young children’s cognitive abilities: The role of child background and classroom context. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210374874

- Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1097–e1103. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2712

For more information please contact: [email protected]