Summary

Across numerous studies, religiosity has been found to protect against suicide attempts and death by suicide (Lawrence, Oquendo, & Stanley, 2016). Research suggests that religion may reduce suicidality by providing a supportive community, influencing beliefs about suicide, and instilling hope. However, religious institutions in the U.S. are not always supportive of LGBTQ identities. Existing research on the association of an LGBTQ individuals’ religiosity with suicidality has not found a protective effect (Barnes & Meyer, 2012; Harris, Cook, & Kashubeck-West, 2008). Further, one study of LGBTQ young adults ages 18–24 found that parents’ religious beliefs about homosexuality were associated with double the risk of attempting suicide in the past year (Gibbs & Goldbach, 2015). Overall, past research has been limited in the inclusion of transgender individuals and has focused primarily on adults. This brief examines how religiosity and parents’ religious beliefs about being LGBTQ are related to suicidality and sharing of identity among LGBTQ youth ages 13 to 24.

Results

One in four LGBTQ youth reported that religion was “important” or “very important” to them; however, youth who reported religion as important did not have reduced risk of attempting suicide. Rates of endorsing religion as important were comparable across socioeconomic status (SES), gender identity, and age. More Black (33%) and American Indian/Alaskan Native (33%) youth reported religion as important.

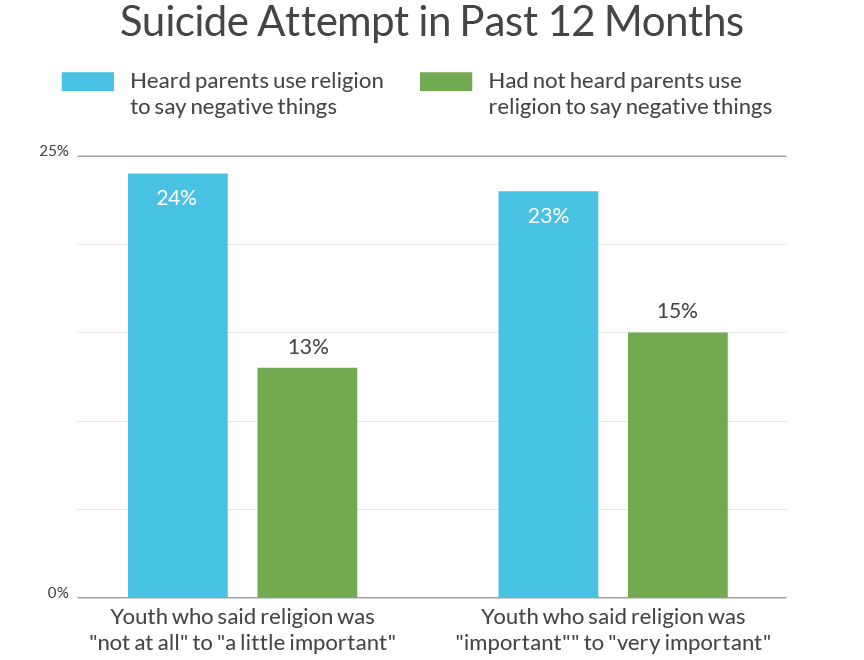

LGBTQ youth who report not hearing their parents use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ were at significantly reduced risk for attempting suicide in the past year, regardless of whether religion was important to them. Overall, half (51%) of youth reported not hearing their parents use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ, with lower rates among youth who said religion was important to them (44%). When adjusting for other related factors, LGBTQ youth who had not heard their parents use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ were at half the risk for attempting suicide in the past year compared to those who had (aOR = 0.50, p<.001).

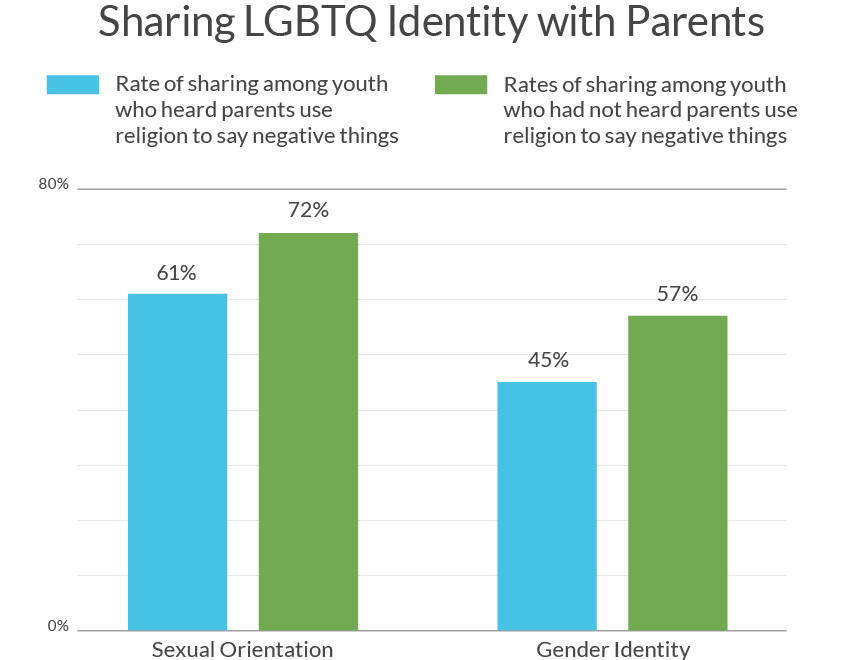

Rates of sharing sexual orientation or gender identity with parents were significantly higher among youth who did not report hearing their parents use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ. 72% of youth who did not hear their parents use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ shared their sexual orientation with a parent compared to 61% who did hear their parents use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ. Among transgender and/or nonbinary youth, 57% who did not hear their parents use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ shared their gender identity with a parent compared to 45% who did.

Methodology

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data through an online survey between February and September 2018. A sample of LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. A total of 34,808 youth consented to complete The Trevor Project’s 2019 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, with a final analytic sample of 25,896. To assess religiosity, youth were asked, “How important is your religion to you?” on a 4-point scale from “not at all important” to “very important.” Youth were also asked to respond to the statement, “I have heard my parents (or guardians) use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ,” with responses on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Youth who endorsed “agree” or “strongly agree” were coded as endorsing this item. Youth were included as sharing if they endorsed “your parents” when asked “Who have you shared your sexual orientation with” or “Who have you shared your gender identity with?” Past year suicide attempt was assessed with the question “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” A logistic regression model examined the odds of a past year suicide attempt for youth who heard their parents use religion to say negative things about being LGBTQ compared to those who did not. This model was adjusted for age, SES, gender identity, race/ethnicity, and religion importance.

Looking Ahead

Unlike in studies among straight/cisgender youth, no statistically-significant protective effect was found between religiosity and suicide attempts for LGBTQ youth. However, whether or not religion was used to say negative things about being LGBTQ was significantly associated with youth sharing their sexual orientation or gender identity with their parents and with suicide attempts in the past year. These findings highlight the complexities involved in understanding the role of religion in preventing suicide. For parents and caregivers, there is a need for increased awareness of the way negative religious statements about being LGBTQ can impact a youth’s risk for suicide as well as the likelihood that the youth chooses to “come out” to them. Further, individuals providing care to LGBTQ youth need to be cognizant that a substantial proportion of LGBTQ youth find religion to be important to them and should work to integrate religion as a strength, including helping them navigate holding on to their faith in a healthy way if they wish to do so.

Our previous research has highlighted the need for increased attention to the needs of Black and American Indian/Alaskan Native LGBTQ youth. These youth were also most likely to report that religion was important to them. Given previous research pointing to the protective impact of religion on suicidality, there is a need to encourage religious communities to be LGBTQ-inclusive and to help youth find supportive religious institutions, particularly among Black and American Indian/Alaskan Native youth. At The Trevor Project, our crisis services team works 24/7 to provide support that recognizes the benefits religion can provide for some while presenting conflicts for others, and for some youth both benefits and conflicts. Our public education team also provides trainings to help counselors, educators, and other stakeholders understand the unique needs of LGBTQ youth. Further, our research team continues to disseminate data on the diverse lives of LGBTQ youth so that The Trevor Project and other stakeholders will be best prepared to understand and protect all LGBTQ youth.

| ReferencesBarnes, D. M., & Meyer, I. (2012). Religious affiliation, internalized homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82, 505–515Gibbs, J. J., & Goldbach, J. (2015). Religious conflict, sexual identity, and suicidal behaviors among LGBT young adults. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(4), 472-488.Harris, J. I., Cook, S. W., & Kashubeck-West, S. (2008). Religious attitudes, internalized homophobia, and identity in gay and lesbian adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 12, 205–225.Lawrence, R. E., Oquendo, M. A., & Stanley, B. (2016). Religion and suicide risk: A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 20, 1-21. |

For more information please contact: [email protected]