EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The LGBTQ community is comprised of a considerable proportion of youth who are multisexual (i.e. those who are attracted to more than one sex and/or gender), often colloquially referred to as bisexual. Prevalence data suggest almost twice as many LGBTQ youth identify as multisexual compared to gay or lesbian. Youth with a multisexual identity may experience stigma from both the non-LGBTQ population, for having an identity that is not heterosexual, and from within the LGBTQ community for not having exclusively same-gender attractions and relationships (i.e. monosexually-identified). However, very little research has specifically explored the mental health of multisexually-attracted youth. Interestingly, as researchers have historically aggregated all LGBTQ youth into one group, what we know about the LGBTQ youth community could arguably be considered predominantly findings about multisexual youth, given its relative size. This report contributes to our understanding of multisexual youth mental health by using data from a national sample of nearly 25,000 multisexual youth ages 13–24 who participated in The Trevor Project’s 2020 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health to build upon and extend the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBS) findings reported in The Trevor Project’s research brief, Bisexual Youth Experience.

Key Findings

Multisexual youth represent a diversity of sexual, racial, and gender identities.

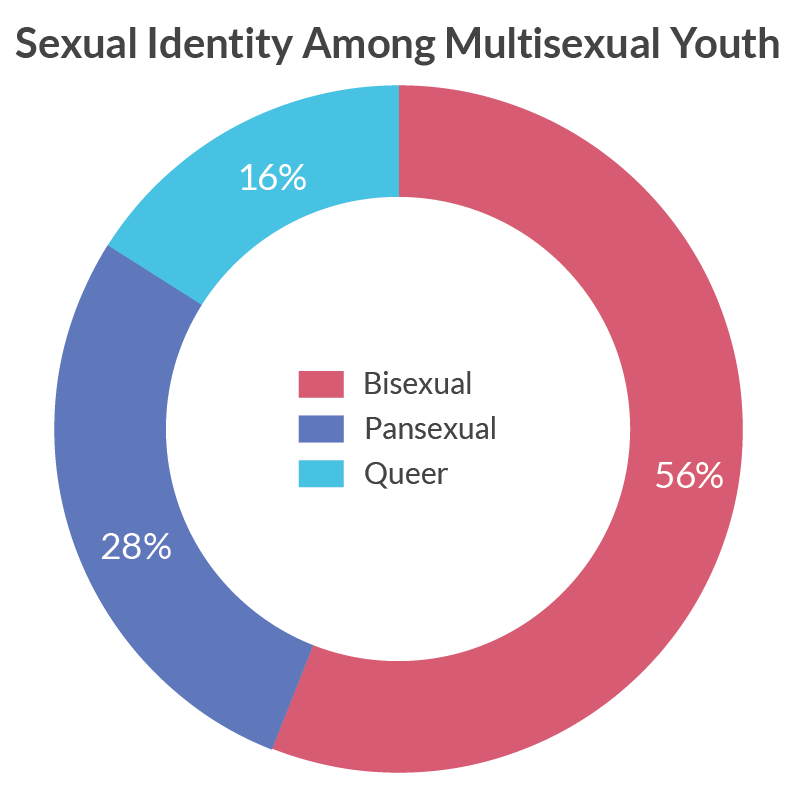

- 56% of multisexual youth identified as bisexual, 28% as pansexual, and 16% as queer

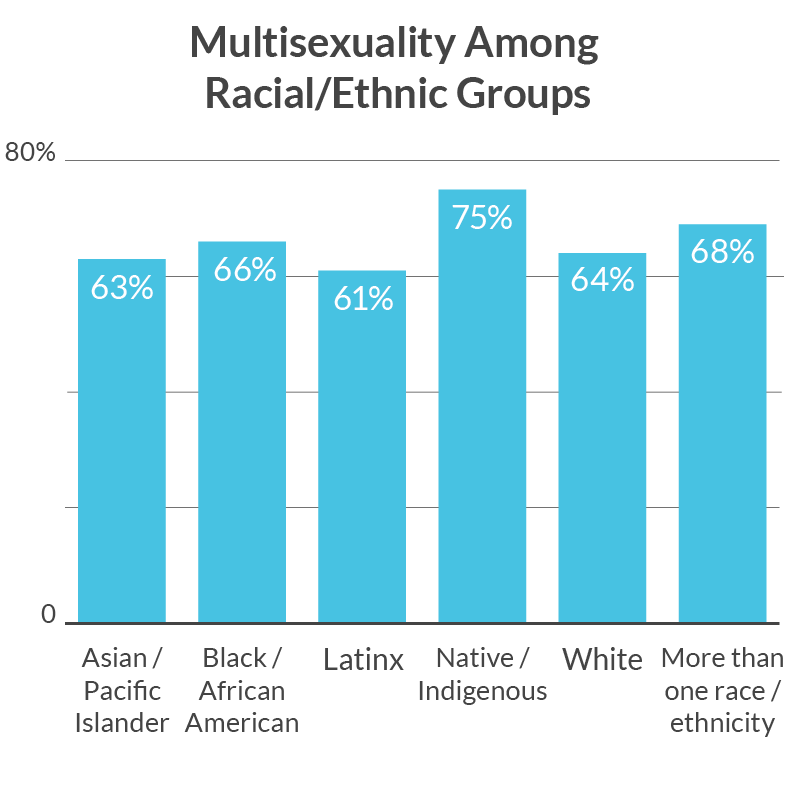

- Multisexual youth were represented among each race or ethnicity assessed in our survey

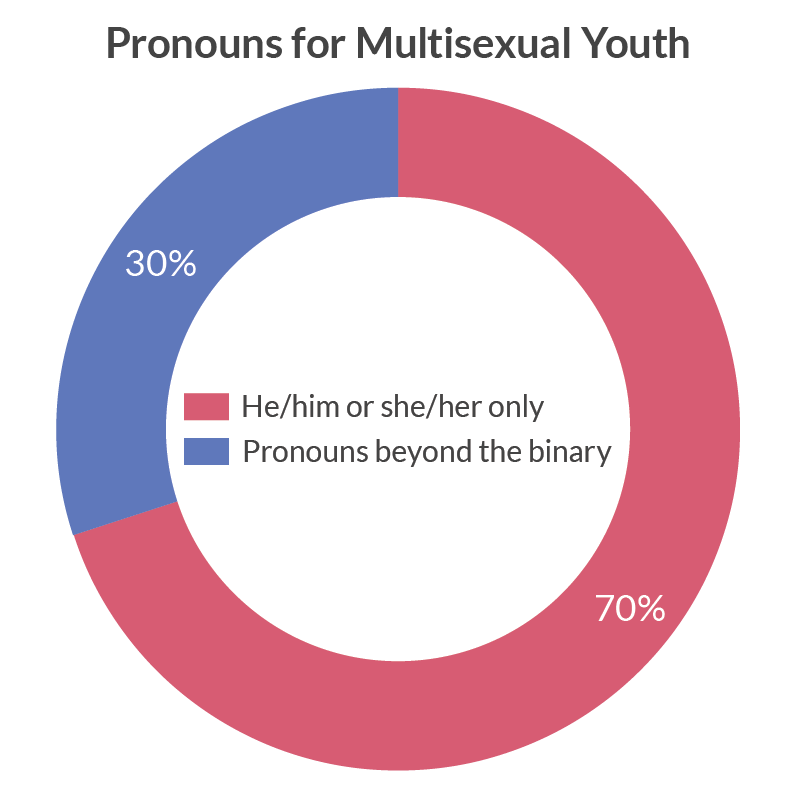

- More than 1 in 3 multisexual youth used pronouns or pronoun combinations that fall outside of the binary construction of gender

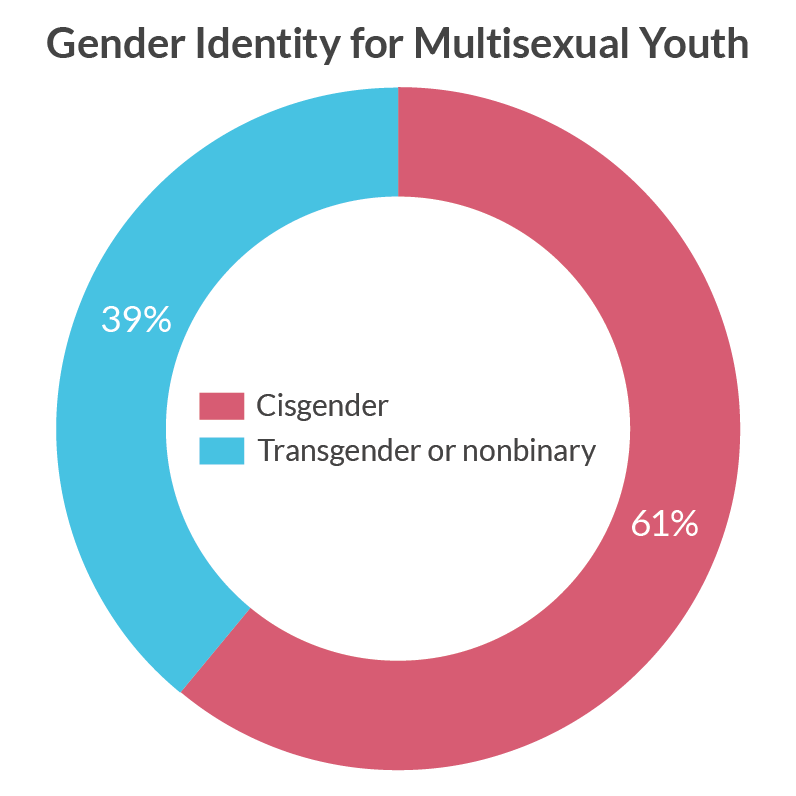

- 39% of multisexual youth identified as transgender or nonbinary

Multisexual youth report mental health challenges, including suicidal ideation, at rates often higher than monosexual youth

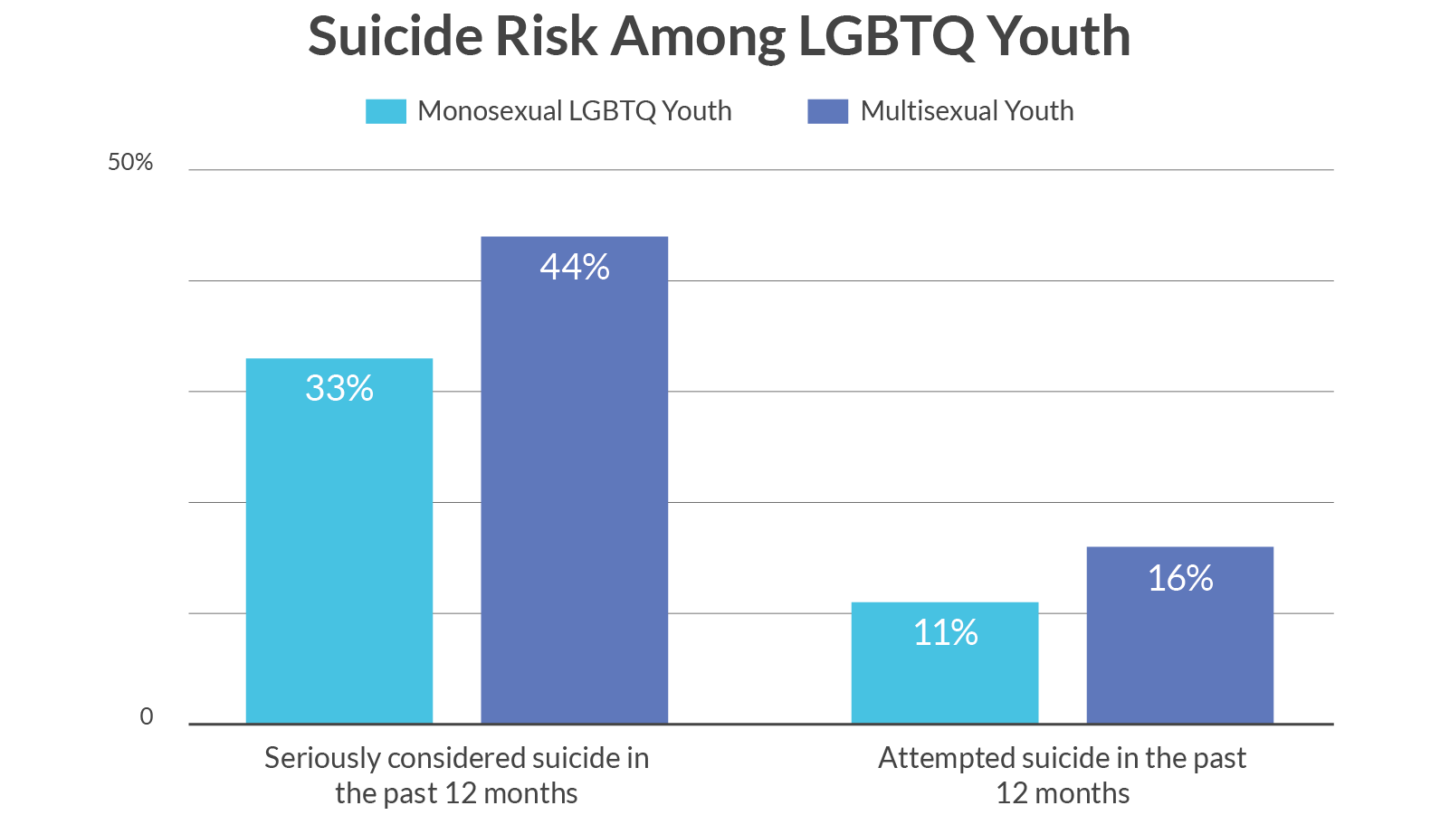

- 44% of multisexual youth seriously considered suicide in the past 12 months, including 54% of transgender and nonbinary multisexual youth

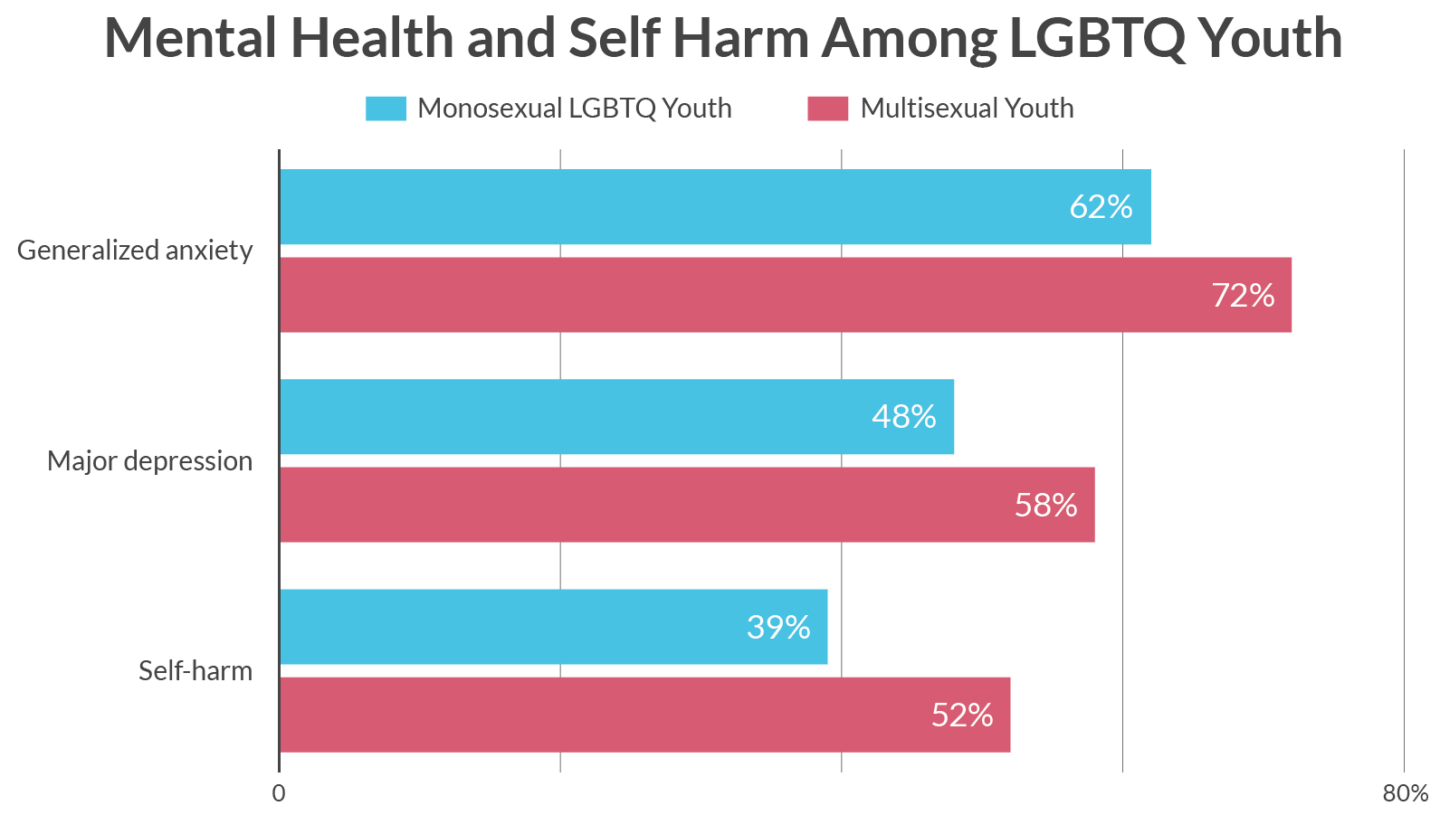

- Self-harm was reported in 52% of multisexual youth

- 72% of multisexual youth reported symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in the past two weeks

- 58% of multisexual youth reported symptoms of major depressive disorder

Our findings point to many risk factors contributing to poor mental health and suicide risk among multisexual youth.

- 10% of multisexual youth reported having undergone conversion therapy

- Nearly 60% of multisexual youth reported that someone tried to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity

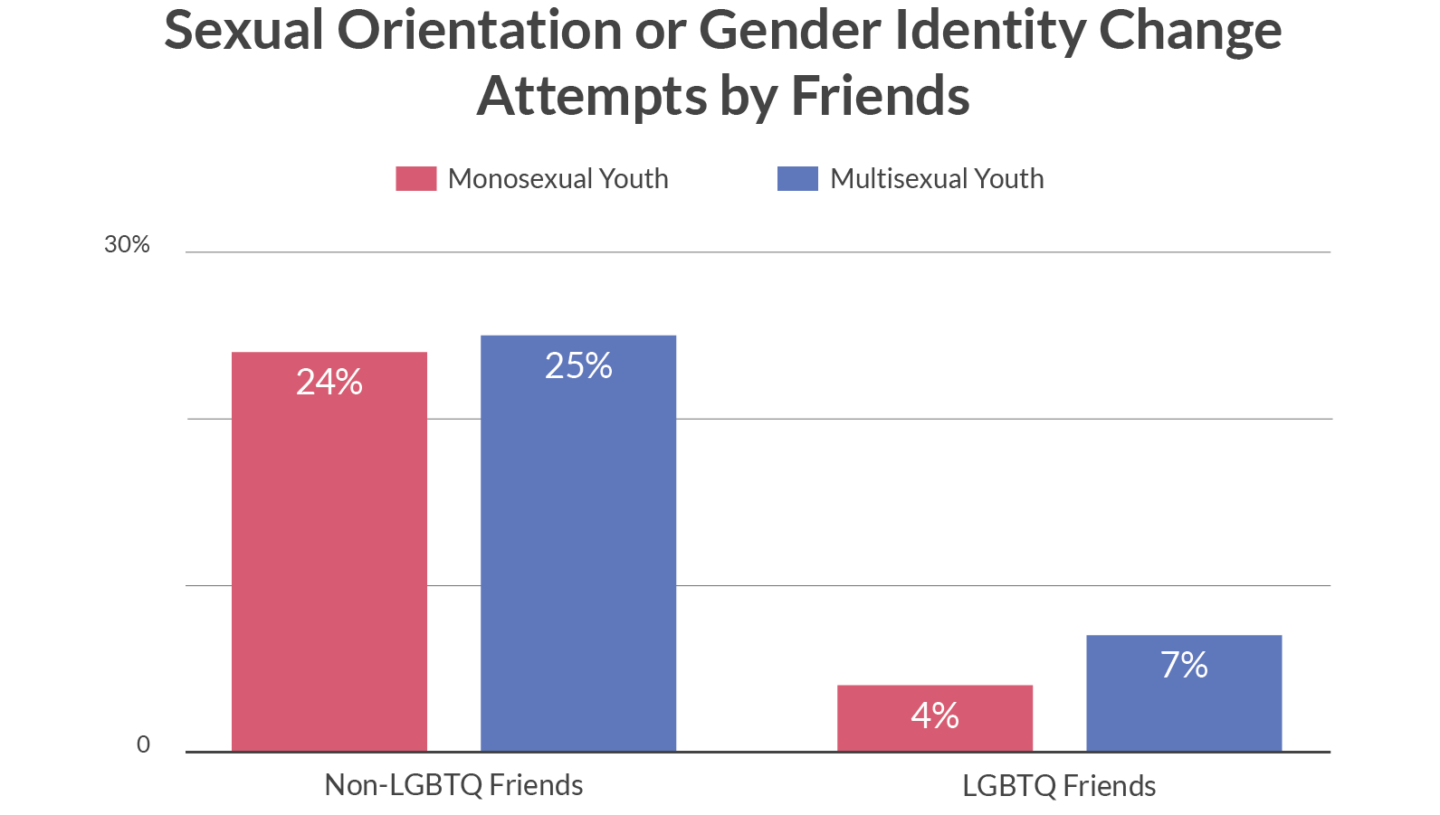

- More multisexual youth experienced an LGBTQ friend attempting to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity compared to monosexual youth

- Nearly half (48%) of multisexual youth reported having been bullied in the past 12 months

- 12% of multisexual youth, who had ever dated, reported experiencing dating violence in their lifetime, including 18% of multisexual transgender women

Multisexual youth also shared many opportunities where they find resiliency and ways to thrive.

- Most (86%) multisexual youth reported high levels of support from at least one family member, friend, or special person

- 76% of multisexual youth reported access to at least one in-person LGBTQ-affirming space

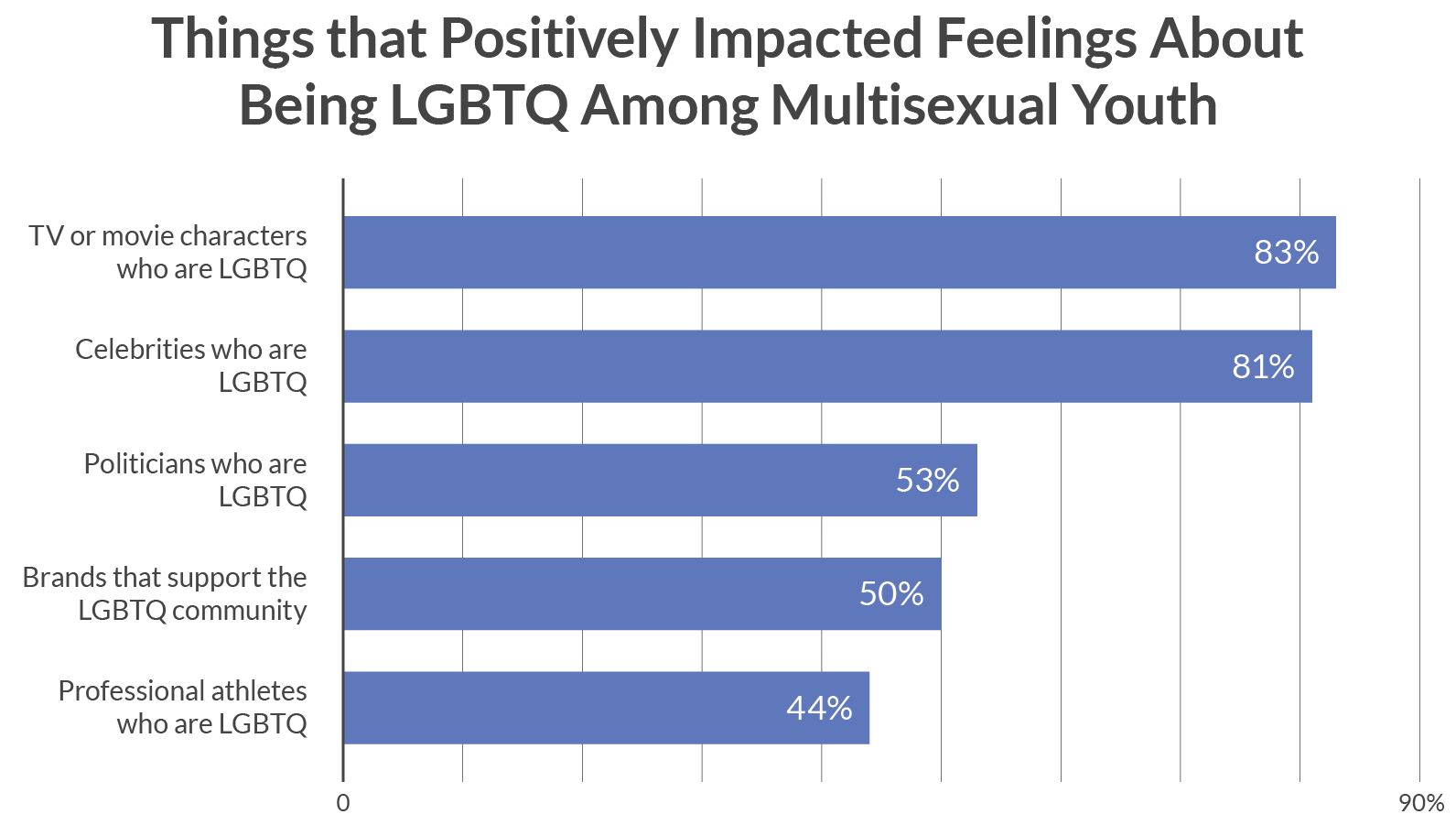

- Multisexual youth shared that TV or movies characters who are LGBTQ (83%) and celebrities who themselves are LGBTQ (81%) made them feel good about being LGBTQ

Methodology Summary

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data using an online survey platform between December 2, 2019 and March 31, 2020. An analytic sample of 40,001 youth ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. Youth were asked, “Which of these options best describes your sexual orientation. We understand that there are many different sexual identities (e.g. asexual, sapphic, sapiosexual, etc.), please pick the one that best describes you here first, and you will be given the option to elaborate in the next question” with options: straight or heterosexual, gay or lesbian, bisexual, queer, pansexual, or I am not sure. Youth were then given the opportunity to select additional sexual orientations or identities that applied to them from a list of over 30. The current analyses include the 24,852 youth who identified as either bisexual, queer, or pansexual in the initial question, henceforth referred to as multisexual or multisexually-attracted unless otherwise specified.

Recommendations

Multisexual youth report rates of mental health challenges and suicide risk that are often higher than those reported by LGBTQ youth who are attracted to one gender. Multisexual youth are confronted with risk factors that are similar to those of other LGBTQ youth but also very different, such as having friends who are members of the LGBTQ community attempt to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity. As is often the case when individuals hold more than one stigmatized identity, transgender and nonbinary multisexual youth show particularly high rates of poor mental health and risk outcomes. The multisexual youth experience must be specifically addressed in outreach and prevention programs. Efforts and initiatives aimed at the LGBTQ community must foster greater inclusion by refraining from using language that implies only same-sex attractions and by explicitly naming multisexual identities. Further, increased multisexual visibility in the media can have a profound impact on the mental health and well-being of LGBTQ youth. Finally, research must acknowledge the relative size of the multisexual youth population and make amends with the overall lack of findings specific to this group.

BACKGROUND

Copious research has found that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth experience significant mental health and suicide disparities compared to their straight and cisgender peers. Overall, LGBTQ youth report higher rates of depression, anxiety, and other forms of emotional distress compared to straight, cisgender youth (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020; Stettler & Katz, 2017; Underwood, et al., 2020) and are also more likely to engage in self-harm, seriously consider suicide, and to attempt suicide (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020; Underwood et al., 2020). LGBTQ youth also face external challenges such as higher rates of bullying (Birkett et al., 2009), discrimination (Almeida et al., 2009), and other forms of victimization. Although the LGBTQ youth community is often examined as a singular group, it consists of youth with valid and distinct identities.

Multisexual youth make up the vast majority of the LGBTQ youth community. For example, more than half of LGBTQ youth identified as bisexual on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), where only lesbian, gay, bisexual, and “not sure” were provided as options (Underwood et al., 2020). Multisexuality refers to sexual identities that include romantic and/or sexual attractions to more than one sex or gender, such as bisexual, pansexual, omnisexual, and queer. This is compared to monosexual identities such as gay, lesbian, and straight, which include romantic and/or sexual attractions to one sex and/or gender. Bisexuality has also been defined as romantic and/or sexual attractions to more than one sex and/or gender (Ochs, 2014), and we recognize the term bisexual in both its colloquial and research use to mean just that. However, for the purposes of this report, we use the term multisexual to describe this group of youth as a whole and specifically examine whether there are subgroup differences based on specific identities (i.e. bisexual, pansexual, queer) when appropriate.

Multisexual youth may be more susceptible to poor mental health and suicide risk compared to monosexual youth. Our previous report, Bisexual Youth Experience, using data from the 2015–2017 CDC YRBS, found that multisexual youth who identify as bisexual experienced more risk factors for suicide, such as sexual abuse and bullying compared to gay and lesbian youth (The Trevor Project, 2019). Multisexual youth who were bisexually-identified also reported higher rates of symptoms of major depressive disorder, seriously considering suicide, and attempting suicide compared to gay and lesbian youth (The Trevor Project, 2019). Although LGBTQ youth in general report significantly higher rates of mental health challenges and suicide risk compared to straight cisgender youth, these findings are associated with chronic stress stemming from their marginalized social status, which increases LGBTQ youth’s experiences with identity-based rejection, discrimination, and victimization (Meyer, 2003). Multisexual youth may experience stigma from both the majority population, from having an identity that is not straight, and from within the LGBTQ community for not having exclusively same-gender relationships and attractions (Callis, 2013). This added stigma contributes to the further isolation and erasure of multisexual youth in both the majority and LGBTQ communities. Indeed, youth who identify as bisexual report less access to protective factors, such as family and school connectedness, even when compared to gay and lesbian youth (Saewyc et al., 2009).

Despite their prevalence in the LGBTQ community, research has largely failed to explicitly capture the experiences of multisexual youth. Much research combines all LGBTQ youth together into analyses and findings, often citing sample size concerns. However, this practice has led to a dearth of findings that specifically address multisexual youth, despite the fact that they represent the largest group in the LGBTQ community. Interestingly, the relative size of the multisexual youth population, combined with the practice of aggregating all LGBTQ youth outcomes, suggests that most of the findings we know about the LGBTQ youth community are likely multisexual youth outcomes, though without this specific acknowledgment. The current report contributes to our understanding of multisexual youth mental health by examining data from a national sample of nearly 25,000 multisexual youth ages 13–24.

METHODOLOGY

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data through an online survey platform between December 2, 2019 and March 31, 2020. A sample of individuals ages 13–24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. The final analytic sample consisted of 40,001 LGBTQ youth. In the survey, participants were asked “Which of these options best describes your sexual orientation. We understand that there are many different sexual identities (e.g. asexual, sapphic, sapiosexual, etc.), please pick the one that best describes you here first and you will be given the option to elaborate in the next question.” The response options were: straight or heterosexual, gay or lesbian, bisexual, queer, pansexual, or I am not sure. The question that directly followed asked “Do you have any other way(s) of describing your sexual orientation? Please select all that apply.” and allowed participants to select from a list of 31 sexual identity labels or orientations including “I don’t prefer labels” and “something else (please specify).” The current analyses include the 24,852 youth who identified as either bisexual, queer, or pansexual in the initial question, henceforth referred to as multisexual unless otherwise specified. Although queer is often used as an umbrella term to describe multiple many identities within the LGBTQ community, in our sample only 3.5% of youth who selected “queer” further described their attractions as “only to women or girls” or “only to men or boys.” Thus, the label was predominately used as an identity for those with attractions to multiple genders and/or sexes. Youth who selected straight, gay, or lesbian were categorized as monosexually-attracted (n = 13,766). The overall survey included a maximum of 150 questions, including questions on considering and attempting suicide in the past 12 months taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

RESULTS

Who Are Multisexual Youth?

Overall, 64% of our sample of LGBTQ youth endorsed a multisexual identity. While this ranged from 32% of cisgender males to 80% of nonbinary youth, multisexual youth in our sample are represented in each age, gender identity, and race or ethnicity assessed in the overall survey. Multisexual youth also identified with an array of sexual identities. From our sample of multisexual youth, 56% identified as bisexual, 28% as pansexual, and 16% as queer. Older youth (ages 18–24) represented the majority of those who identified as queer (69%) compared to youth ages 13–17 (31%). Bisexual and pansexual identities were comparable between the two age groups. Cisgender youth endorsed a bisexual identity (39%) at higher rates than both queer or pansexual identities (18%). The reverse was true for transgender and nonbinary youth who endorsed queer and pansexual identities (44%) at higher rates than a bisexual identity (28%).

When given the opportunity, 64% of multisexual youth also chose an additional sexual identity, including 88% of multisexual youth who initially chose queer when asked to describe their sexual orientation. Multisexual youth who chose an additional identity most often chose another multisexual identity such as bisexual (21%), queer (18%), pansexual (13%), or demisexual (9%). Some multisexual youth also identified as asexual (11%) and others endorsed multigender attractions such as biromantic (10%) and panromantic (9%) or multiple relationship orientations such as polyamorous (9%).

One in three (30%) multisexual youth used pronouns or pronoun combinations that fell outside of the binary construction of gender such as they/them exclusively or a combination of they/them and she/her or he/him. This compares to 17% of monosexual youth. Additionally, 39% of multisexual youth in this sample identified as transgender or nonbinary, compared to 25% of monosexual youth.

Mental Health and Well-being Among Multisexual Youth

Multisexual youth report rates of mental health indicators that are similar to the overall LGBTQ sample, but higher than those reported among monosexual LGBTQ youth. Nearly 3 in 4 multisexual youth reported symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in the past two weeks (72%) compared to 62% of monosexual LGBTQ youth. Rates of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms were also higher among transgender and nonbinary multisexual youth (78%) compared to cisgender multisexual youth (67%). Specifically, among multisexual youth, cisgender men reported the lowest rate of generalized anxiety disorder (54%) and transgender men reported the highest (79%).

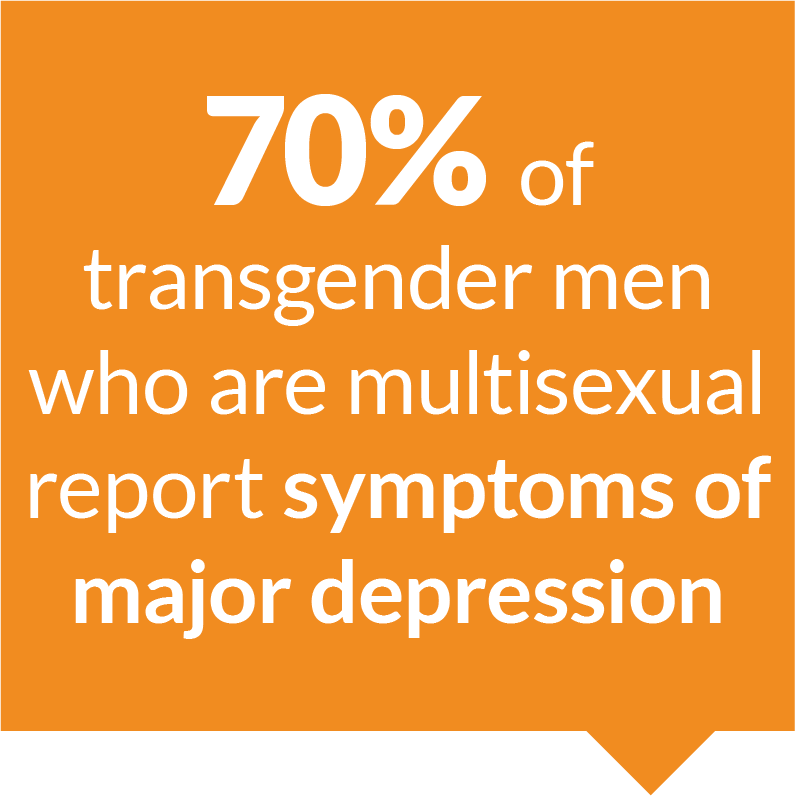

Symptoms of major depressive disorder in the past two weeks were reported by 58% of multisexual youth, a rate higher than that reported by monosexual LGBTQ youth (48%). Similar to anxiety, transgender and nonbinary multisexual youth reported a higher rate of major depressive symptoms (67%) compared to multisexual youth who were cisgender (52%), with cisgender men reporting the lowest rates (42%) and transgender men reporting the highest rates (70%).

Self-harm, or hurting oneself on purpose, was reported by 52% of multisexual youth, compared to 39% of monosexual LGBTQ youth. Consistent with previous findings, rates were higher among multisexual youth who were also transgender and nonbinary (63%) compared to those who were cisgender (47%). Further, transgender men who identified as multisexual reported the highest rate of self-harm (66%).

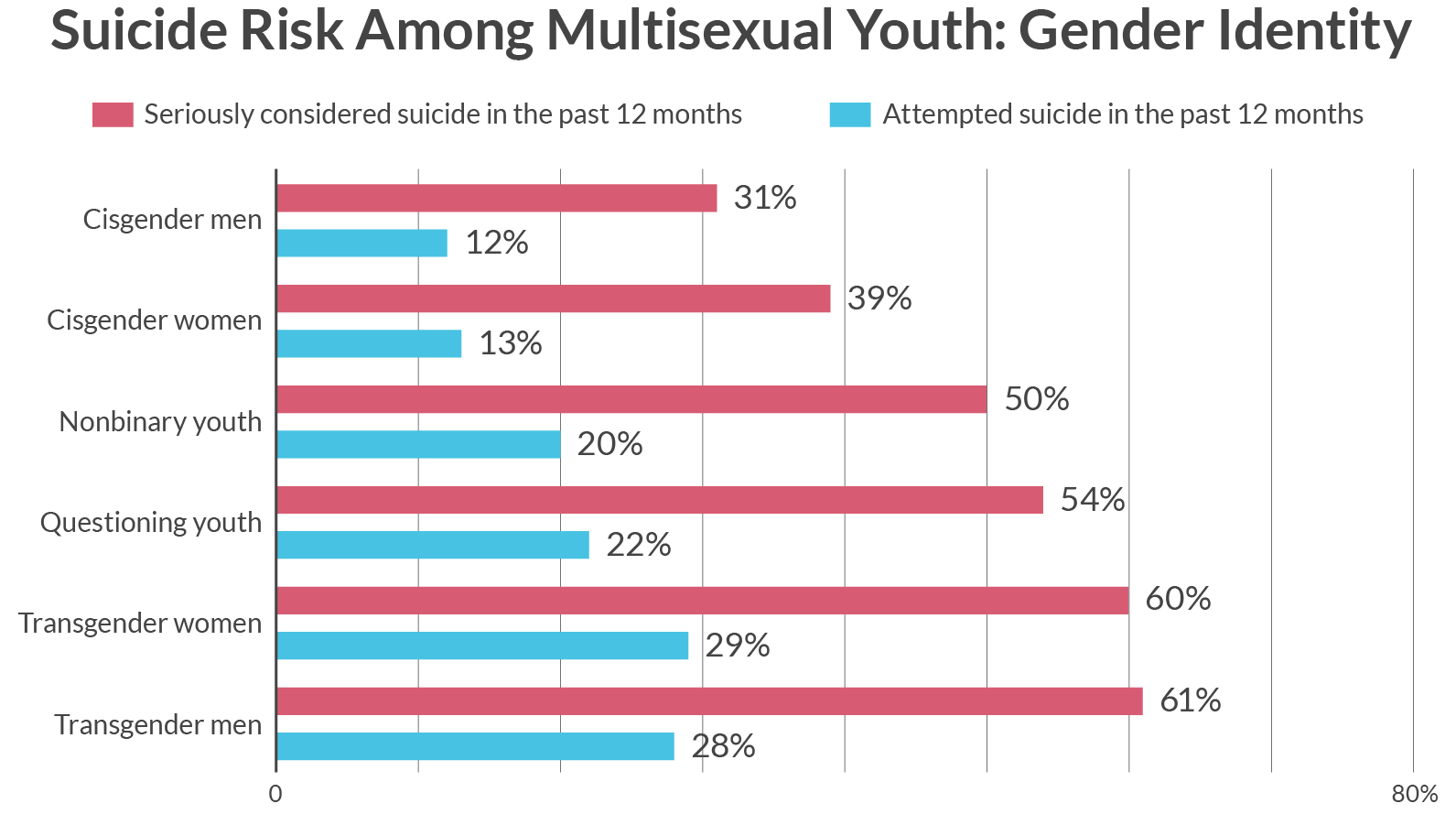

Forty-four percent (44%) of multisexual youth reported seriously considering suicide in the past 12 months, compared to 33% of monosexual youth. This rate was higher among transgender and nonbinary multisexual youth (54%), compared to cisgender multisexual youth (38%) and for 13–17-year-old multisexual youth (51%), compared to older multisexual youth (38%). Furthermore, 3 out of every 5 transgender women (60%) and transgender men (61%) who identified as multisexual seriously considered suicide in the past 12 months.

Overall, 16% of multisexual youth attempted suicide in the past 12 months, including more than 1 in 5 transgender and nonbinary youth who identified as multisexual. Specifically, 28% of transgender men and 29% of transgender women reported a suicide attempt in the past 12 months. Further, nearly twice as many multisexual youth ages 13–17 attempted suicide in the past 12 months (23%) compared to multisexual youth ages 18–24 (12%). Comparatively, 11% of monosexual youth reported a suicide attempt in the past 12 months.

Conversion Therapy and Change Attempts Among Multisexual Youth

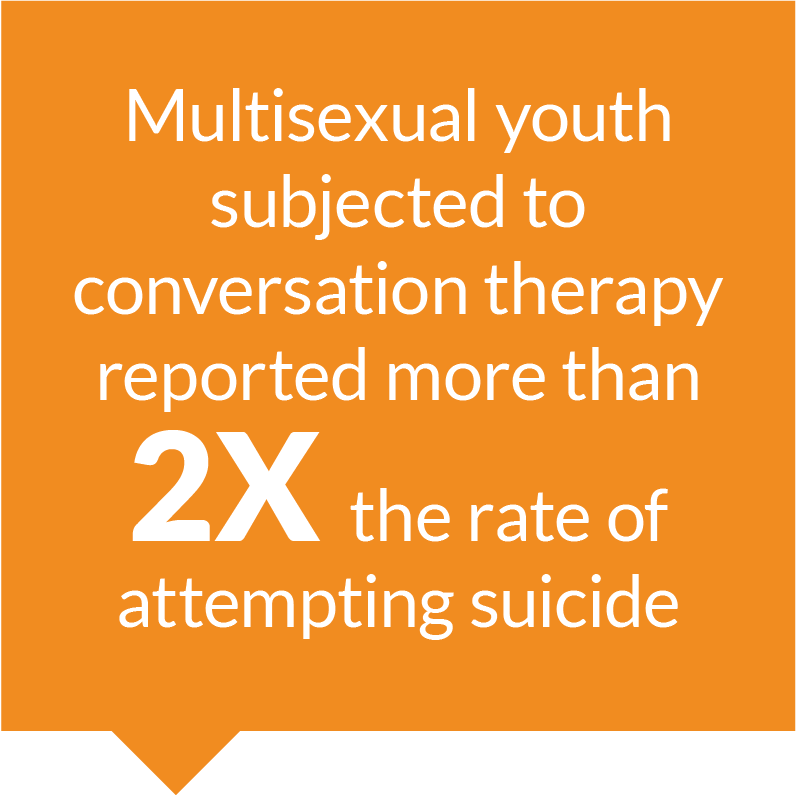

While there is mounting evidence of the negative outcomes associated with conversion therapy (Green, et al., 2020), it is still being practiced legally in the majority of states in the United States. Conversion therapy includes attempts by licensed professionals (e.g. psychologists or counselors) or practices by religious leaders to alter sexual attractions and behaviors, gender expression, or gender identity. Generally thought to be something associated with youth who are gay or lesbian, 10% of multisexual youth reported having been subjected to conversion therapy, 79% of whom did so before age 18. Multisexual youth who were transgender and nonbinary reported more than double the rate (17%) of having been subjected to conversation therapy compared to cisgender multisexual youth (7%) Multisexual youth subjected to conversion therapy reported more than twice the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (32%) compared to those who were not exposed to this practice (14%).

Much broader, but certainly inclusive of conversion therapy, are sexual orientation or gender identity change attempts. These are attempts by individuals to convince a young person to change their sexual orientation or gender identity. This is often thought to be someone attempting to convince another person to be straight or cisgender; however, it can also include others attempting to convince someone to be monosexual instead of multisexual. Indeed, more than half (58%) of multisexual youth reported that someone attempted to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity. This included 54% of bisexual youth, 64% of pansexual youth, and 65% of queer youth. With the exact same rate as the overall LGBTQ youth sample, multisexual youth reported that parents/caregivers (35%) and friends (28%) were the most common people reported to have attempted to convince them to change. However, where multisexual youth noticeably differ from other LGBTQ youth is in the type of friends who are engaging in these change attempts. While multisexual youth reported similar rates of change attempts from non-LGBTQ friends (25%) when compared to monosexual youth (24%), multisexual youth reported change attempts from LGBTQ friends at nearly twice the rate (7%) as monosexual youth (4%). Multisexual youth who reported any change attempt had suicide attempt rates more than twice as high (21%) as those who did not (9%).

Discrimination and Victimization Among Multisexual Youth

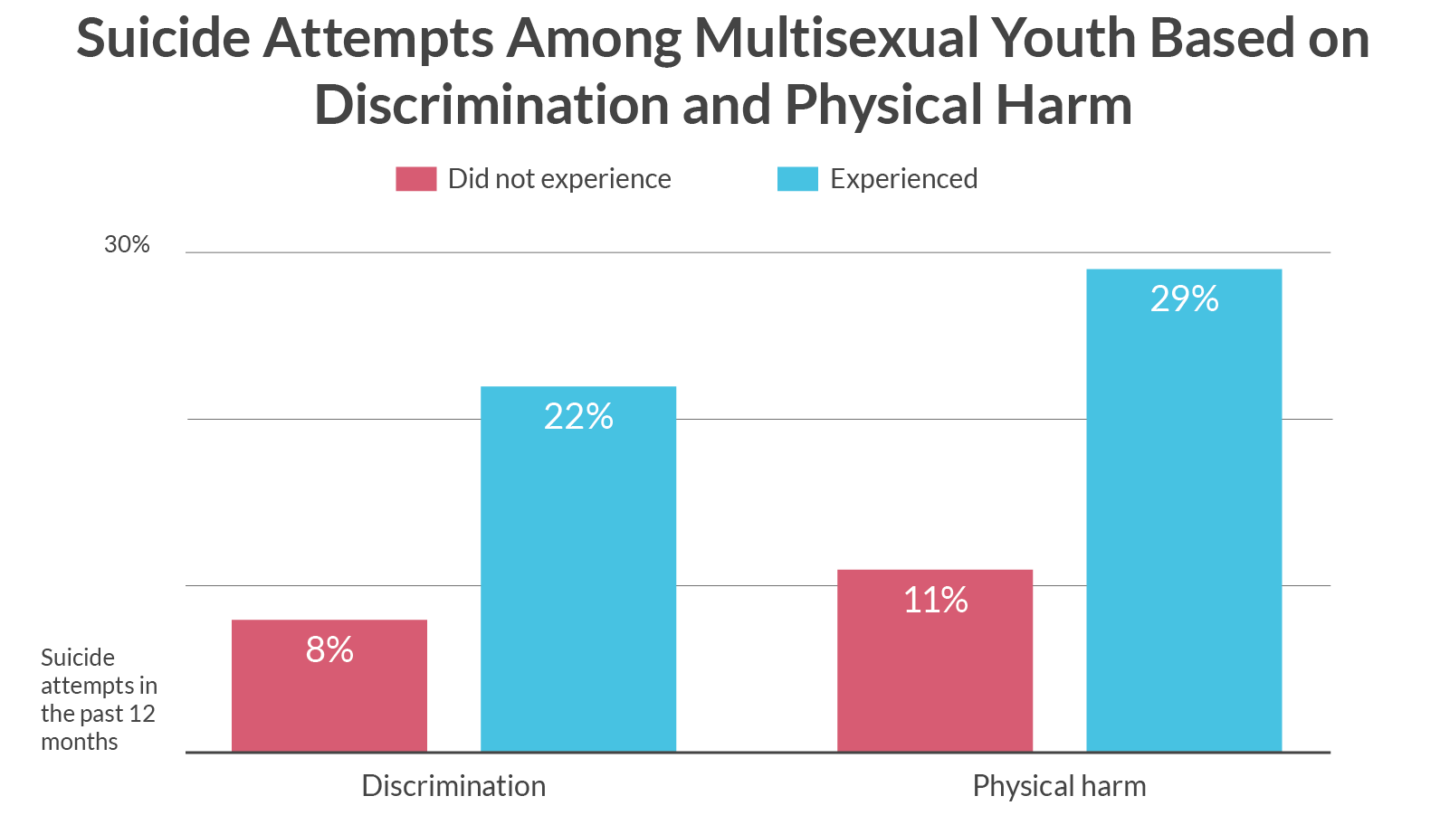

While multisexual youth’s rates of discrimination and physical threat or harm due to their sexual orientation or gender identity were lower than those reported by monosexual youth, these acts were still associated with higher rates of attempting suicide for multisexual youth.

Overall, 58% of multisexual youth reported ever having experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity compared to 65% of monosexual youth. Multisexual youth who reported ever having experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity reported nearly three times the rate of past-year suicide attempts (22%) compared to those who did not (8%).

Furthermore, nearly 1 in 3 (31%) multisexual youth have ever been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity compared to 36% of monosexual youth, and past-year experiences with physical threat or harm were nearly the same for both multisexual (18%) and monosexual (19%) youth. Monosexual youth who were physically harmed or threatened due to their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year reported more than two times the rate of suicide attempts in the past 12 months compared to those who were not. This suggests that the association between physical harm (or the threat of it) and suicide attempts is the same for multisexual youth as it is for monosexual youth.

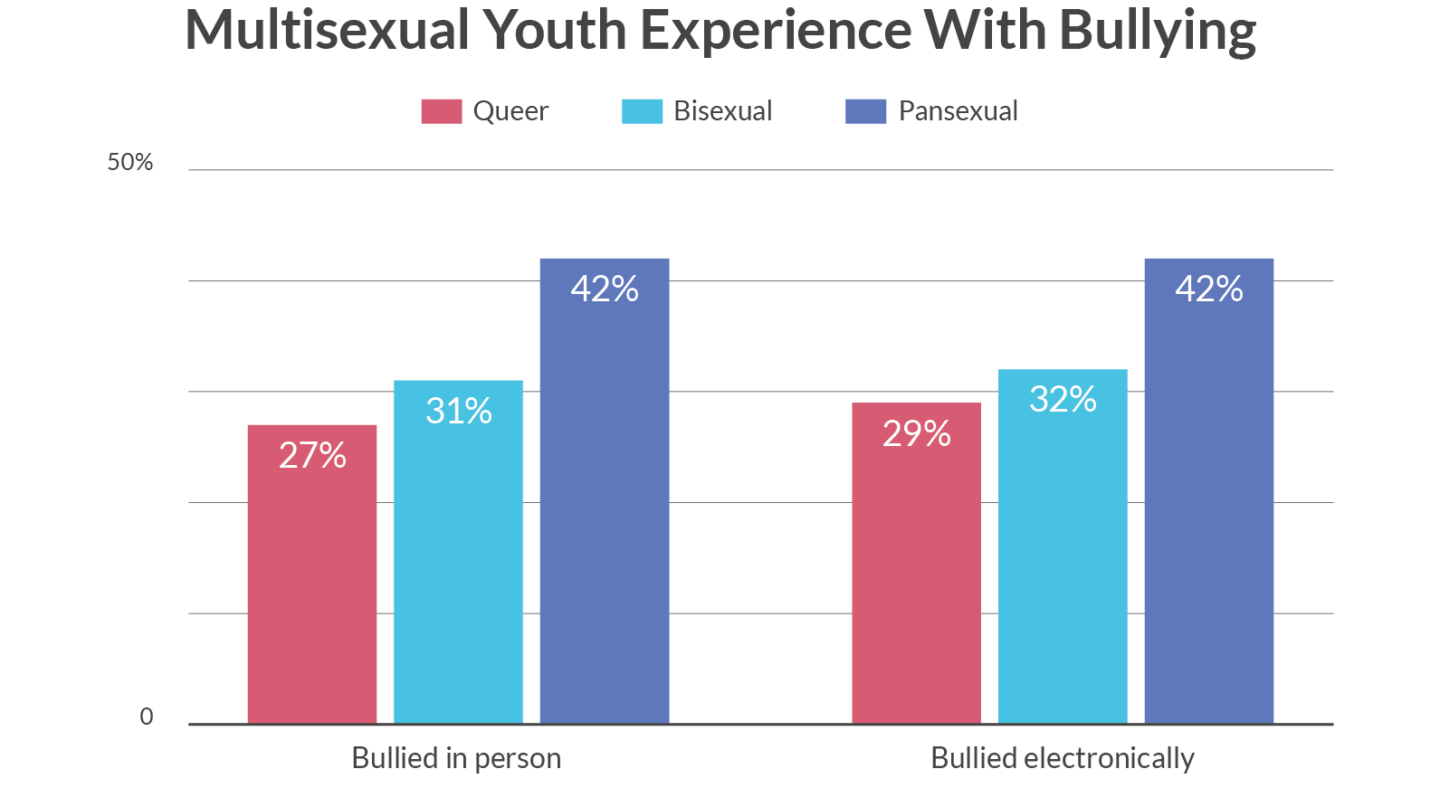

In contrast to discrimination and physical harm, multisexual youth reported higher rates of bullying–both in person and electronically–compared to monosexual youth. Nearly half of multisexual youth (48%) reported having been bullied in the past 12 months. This included one in three multisexual youth (33%) who reported having experienced in-person bullying compared to 29% of monosexual youth. Electronic, or bullying through text or social media, was reported by 34% of multisexual youth compared to 30% monosexual youth. Multisexual youth who reported either type of bullying reported more than three times the rate of a past-year suicide attempt compared to youth who did not.

Twelve percent (12%) of multisexual youth who dated or went out with someone in the past 12 months reported having experienced dating violence and multisexual youth who were survivors of dating violence reported more than twice the rate of past-year suicide attempts (40%) compared to multisexual youth who were not (15%). Among multisexual youth, transgender and nonbinary multisexual youth reported higher rates of dating violence (14%) compared to cisgender multisexual youth (11%). In particular, transgender women who identified as multisexual reported the highest rates of dating violence (18%), and cisgender multisexual women reported the lowest (11%).

Supportive People and Places for Multisexual Youth

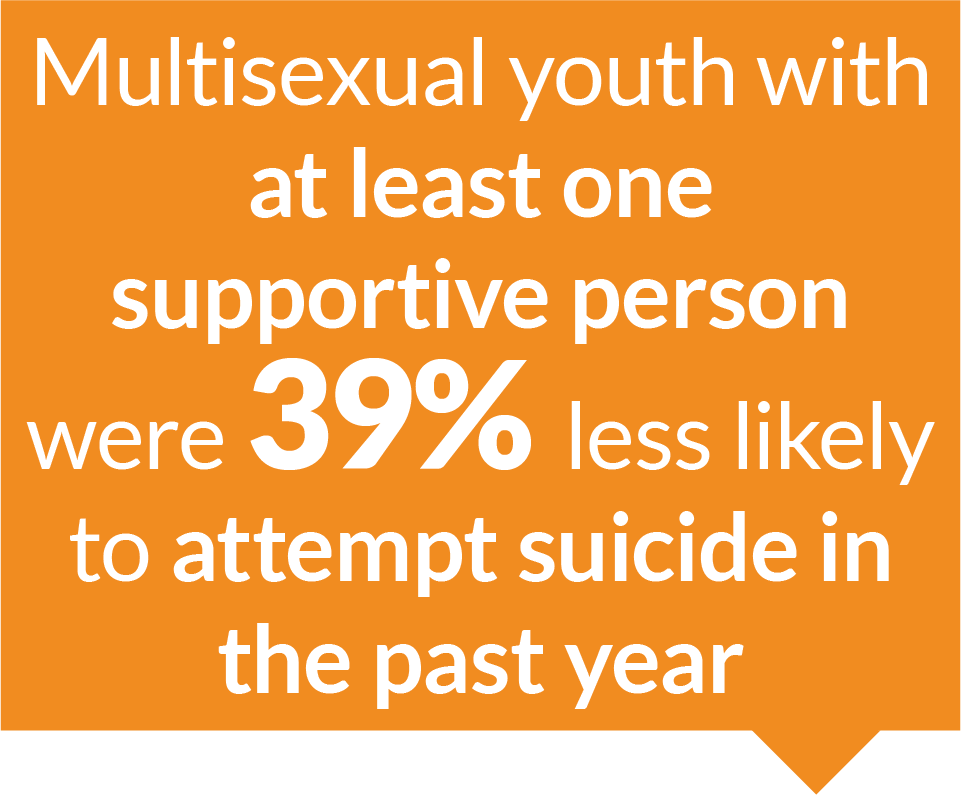

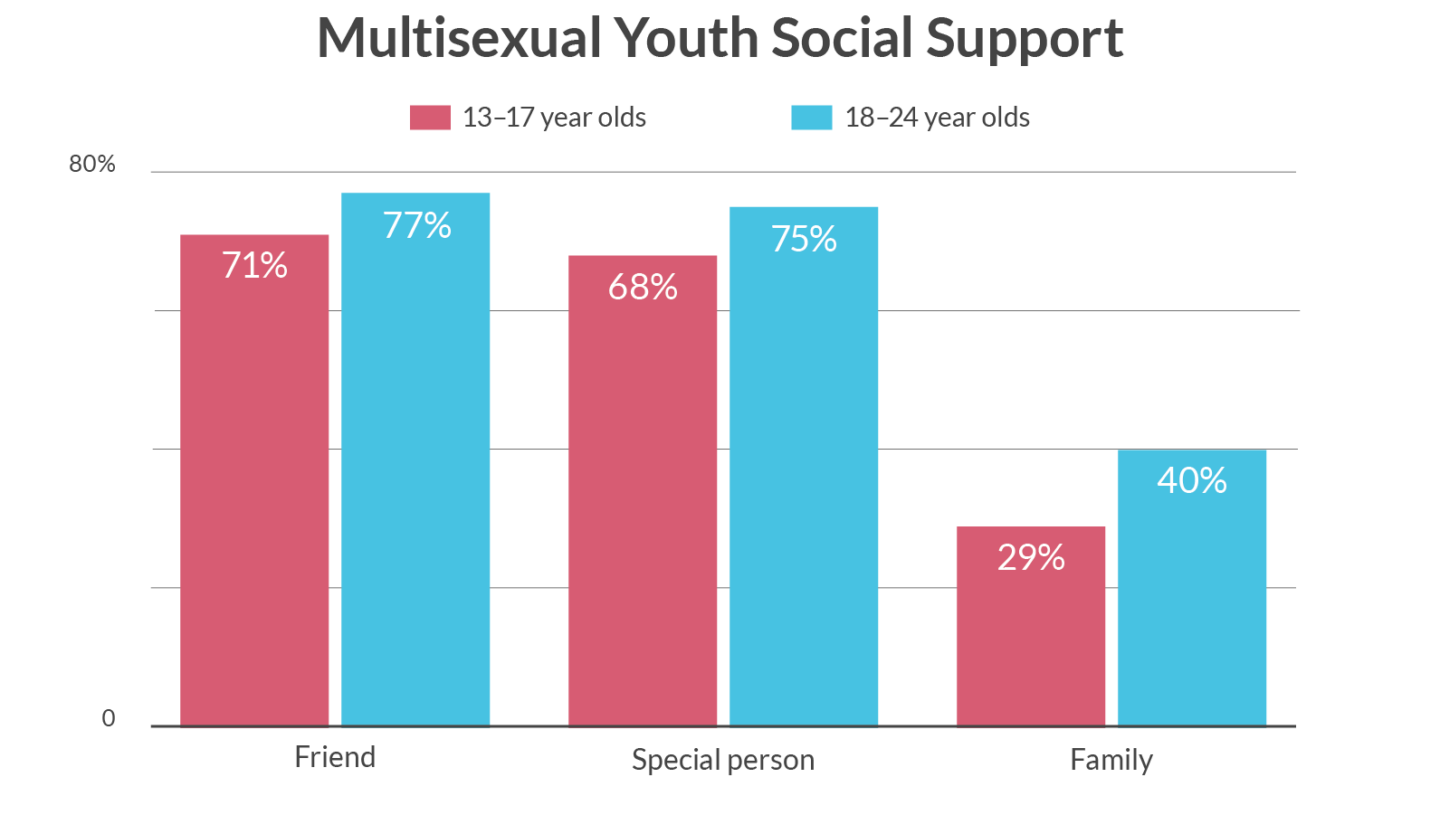

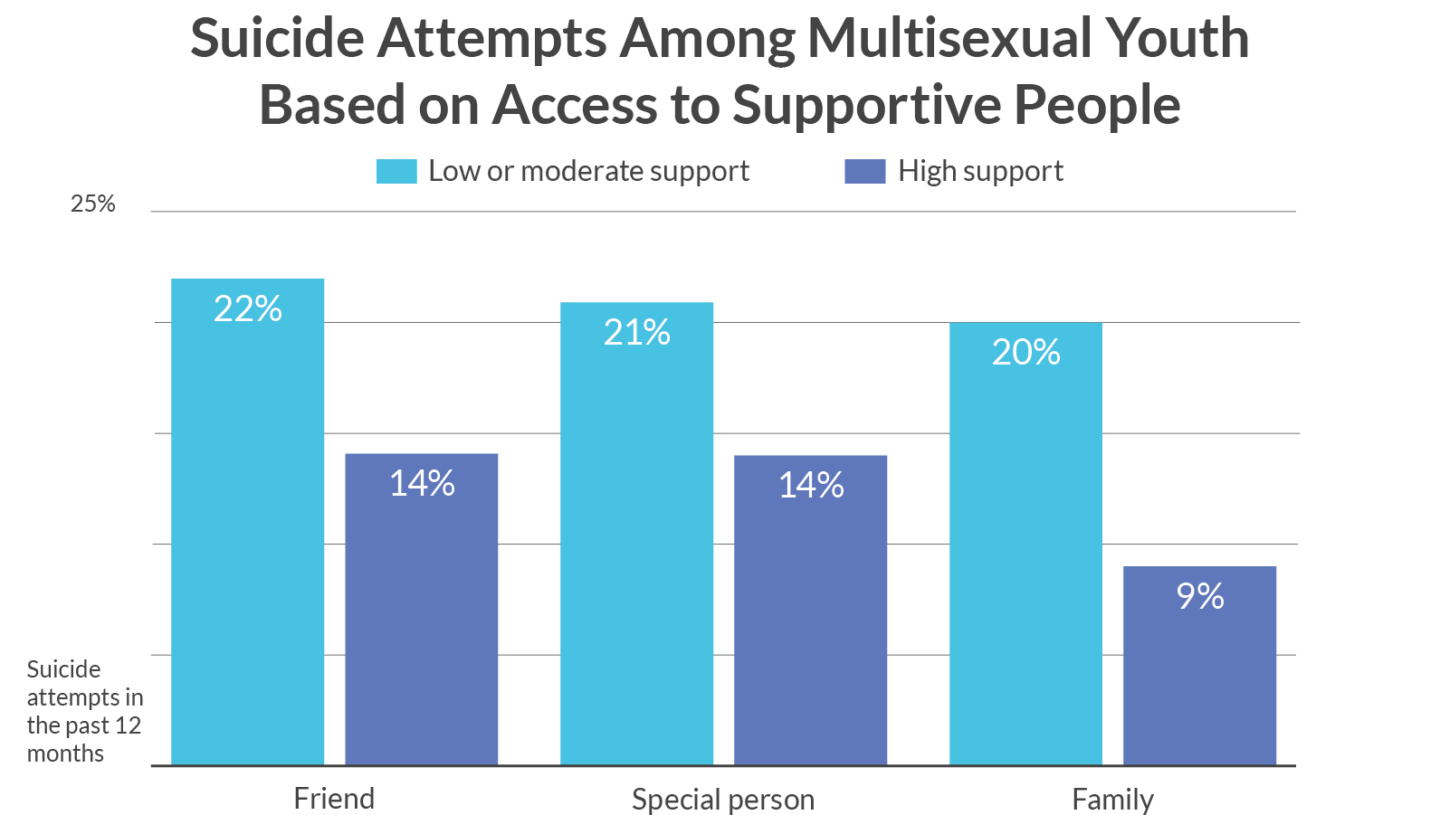

Despite the many negative findings associated with poor mental health and well-being for multisexual youth, it is important to also remember that they are continuing to find ways to thrive and get support. Similar to monosexual youth, multisexual youth thrive when they are able to find support in people (e.g. family) and places (e.g. school). Most (86%) multisexual youth report having high levels of support from at least one person in their life among family members, friends, or a special person, such as a romantic partner or someone else perceived as special outside of family or friends. Supportive relationships are protective: among multisexual youth who reported high levels of support from at least one person, 15% reported attempting suicide in the past year compared to 25% who did not have that support. However, fewer young multisexual youth (ages 13–17) report having supportive people in their lives compared to older multisexual youth (ages 18–24).

Multisexual youth showed lower rates of suicide attempts in the past year within each category of support. Similar to monosexual youth, family support was particularly meaningful for multisexual youth — youth who had high family support reported half the rate of past-year suicide attempts (9%) compared to those who did not (20%). However, family support was only reported by a little over 1 in 3 multisexual youth (35%) and even fewer multisexual youth who were younger (29%).

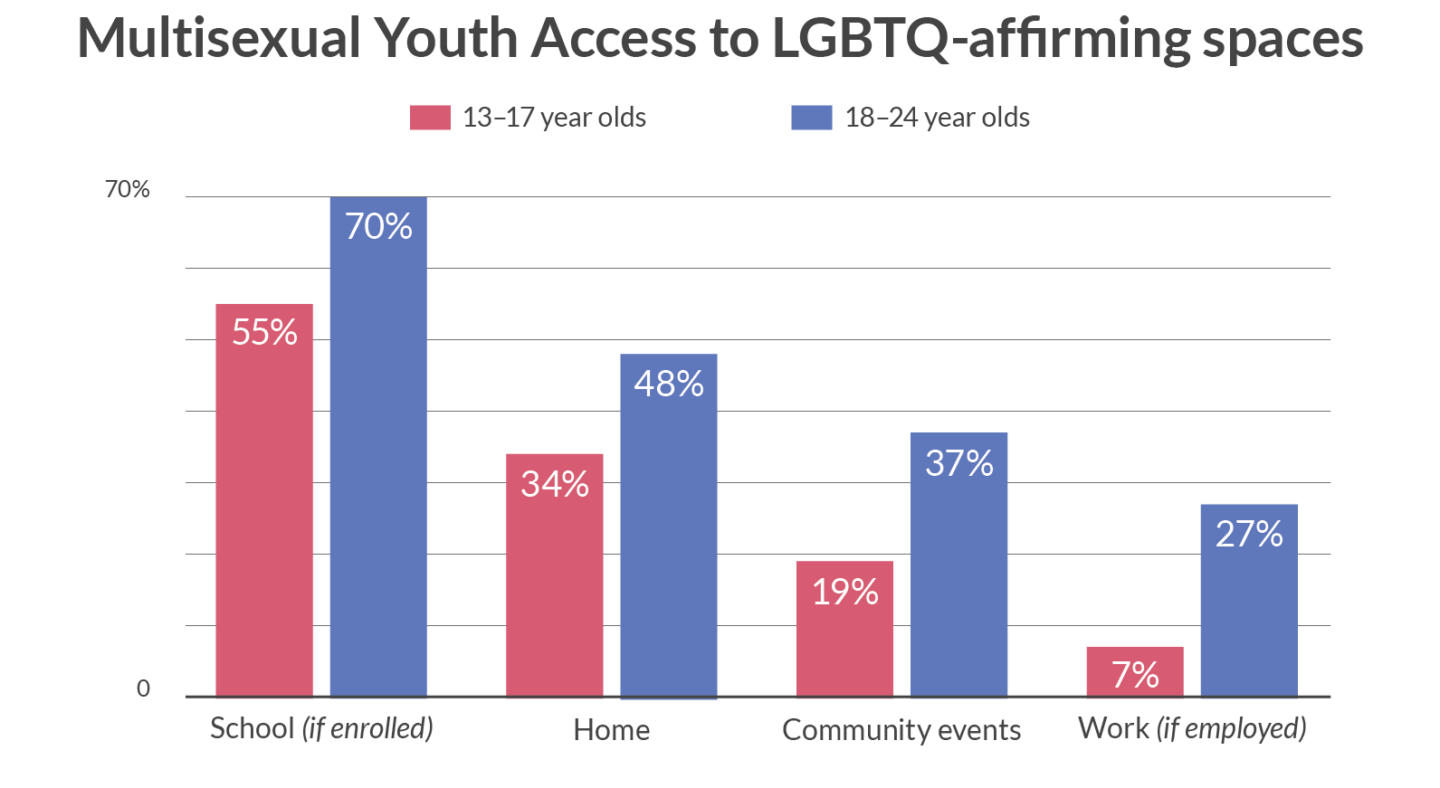

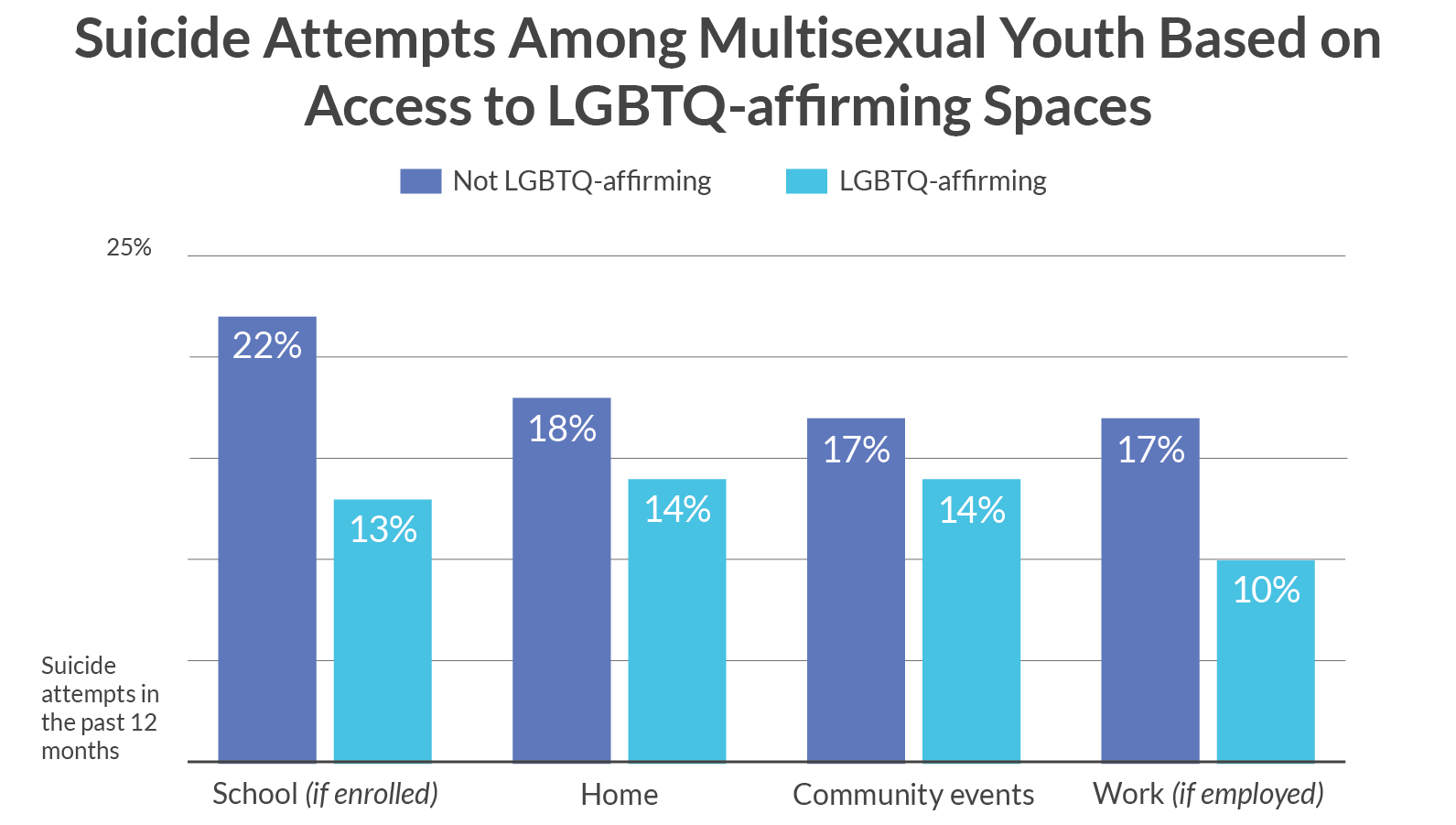

Finding LGBTQ-affirming spaces is also protective for multisexual youth mental health in the same way that it is for monosexual youth. Nearly 4 out of 5 (76%) multisexual youth report access to at least one in-person LGBTQ-affirming space. Multisexual youth who had access to at least one of these in-person LGBTQ-affirming spaces attempted suicide at 50% lower rates (14%) compared to multisexual youth without an in-person LGBTQ affirming space (22%).

However, as with supportive people, multisexual youth reported fewer LGBTQ-affirming spaces compared to monosexual youth, and also fewer young multisexual youth reported having at least one LGBTQ-affirming space (69%) compared to older multisexual youth (82%).

What Makes Multisexual Youth Feel Good About Being LGBTQ

Multisexual youth, who are often at odds with both the LGBTQ culture and the dominant heteronormative culture, are still able to find ways to feel good about being LGBTQ. When asked, over 80% of multisexual youth said that both TV or movie characters who are LGBTQ (83%) and celebrities who themselves are LGBTQ (81%) positively impacted how they felt about being LGBTQ. Furthermore, politicians and professional athletes who are LGBTQ as well as brands that support the LGBTQ community also positively impacted how they felt about being LGBTQ.

Multisexual youth also provided write-in responses about things that made them feel good about being LGBTQ and they included a variety of responses ranging from the people in their lives to representation in media and political support.

Other Things That Make Multisexual Youth Feel Good About Being LGBTQ

- People in their lives (such as teachers/professors, family members, friends, and coworkers) who were either LGBTQ or LGBTQ supportive

- Positive bisexual visibility

- LGBTQ-affirming churches

- YouTubers, influencers, bloggers, people on TikTok, and other social media users who are LGBTQ or support the LGBTQ community

- Access to books/art about LGBTQ history

- Representation of LGBTQ people in books and video games

- Ads that have LGBTQ people in them

- Adult role models who are LGBTQ

- Anytime someone gives love to the pansexual/bisexual and asexual/aromantic communities

- Artists who are LGBTQ, have LGBTQ themes or characters, or show support for the LGBTQ community

- LGBTQ organizations

- Laws that support the LGBTQ community

- Straight people fighting for queer rights

- Symbols of support (such as pride flags and rainbow crosswalks) in communities

RECOMMENDATIONS

It is imperative that the experiences of multisexual youth are not overlooked. Multisexual youth make up the majority of the LGBTQ youth population and deserve to have their experiences amplified. Multisexual youth identify with a diverse array of sexual identity labels including bisexual, pansexual, queer, and demisexual. Their rates of using pronouns outside of the gender binary and identifying as transgender or nonbinary are higher than among monosexual–gay, lesbian, or straight–youth. The current findings also show that multisexual youth reported higher rates of anxiety, depression, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts compared to monosexual youth. Multisexual youth are also exposed to similar rates of risk factors such as conversion therapy and physical threats or harm as their monosexual peers. Taken together, these findings support increased efforts to specifically address multisexual youth mental health and the development of tailored outreach and prevention programs.

Multisexual youth are more susceptible to unique risk factors for suicide. Our findings show that while multisexual reported similar rates of having had someone attempt to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity, multisexual youth specifically experienced more of this from their LGBTQ friends. In other words, multisexual youth report having experienced nearly twice the rate of having people in the LGBTQ community attempting to convince them to change who they are. This speaks to the experiences of stigma from both the majority population and from within the LGBTQ community for multisexual youth. Peers and friends are often a strong source of support for youth, particularly for LGBTQ youth, and multisexual youth, unfortunately, report having marginalizing experiences from them. Furthermore, multisexual youth reported higher rates of having been bullied, both in-person and electronically, compared to monosexual youth as well experiencing dating violence, particularly among transgender multisexual youth. As these risk factors are associated with increased suicide attempts among multisexual youth, more must be done to specifically address the needs of multisexual youth. These findings also illustrate the diverse experiences of subgroups within the LGBTQ youth population and further exemplify the need for separate analyses when appropriate and possible.

Multisexuality must be explicitly addressed in LGBTQ-inclusivity efforts. Youth who are multisexual, similar to monosexual youth, reported better mental health when they have LGBTQ support from people and are in LGBTQ-affirming environments. However, multisexuality is often forgotten in LGBTQ-inclusivity efforts. Workplace anti-discrimination policies and programs aimed at inclusion should explicitly state that they are inclusive of multisexual identities as well. Furthermore, advocacy efforts and supportive policies should refrain from using language that erases multisexual identities. Failing to acknowledge the very real presence of multisexual youth will diminish efforts to improve the well-being of LGBTQ youth overall.

Increasing visibility of multisexuality in the media can have a profound impact on multisexual youth mental health. Over 80% of multisexual youth reported that seeing LGBTQ television and movie characters made them feel better about being LGBTQ as did representation of LGBTQ people in books, video games, and social media. However, multisexual youth are often not afforded the opportunity to see their own identity reflected in this way. Only 3 of the 118 films depicting characters who identified as LGBTQ had multisexual representation in 2019, none of whom were male-identified (GLAAD Media Institute, 2020). Furthermore, despite making up more than half of the overall LGBTQ population, in the 2020–2021 season, multisexual characters will make up only 28% of the LGBTQ characters on television programs (GLAAD Media Institute, 2021). Companies and brands that do more to reflect the true diversity of the LGBTQ community, including multisexuality, can improve the overall well-being of multisexual youth.

Research must do more to acknowledge multisexual youth and their unique outcomes. The LGBTQ community is made up of diverse identities that may carry different levels of risks or have disparate protective factors (O’Brien et al., 2016). With multisexual youth making up the majority of the LGBTQ youth population, there is no excuse for the disparity in findings specific to this group. As researchers continue to aggregate all LGBTQ youth into one group, what we know about the LGBTQ youth community could arguably be considered predominantly findings about multisexual youth, given its relative size. Indeed, even the current analyses did not show differences between multisexual youth and the overall sample of LGBTQ. They did however show disparities between multisexual and monosexual youth. Yet, studies rarely point to specific findings as they relate to multisexual youth, calling the saliency of LGBTQ youth findings for multisexual youth into question and contributing to the historical and contemporary erasure of this group. Large-scale national surveys certainly have the sample size capabilities and should be used to further explore the experiences of multisexual youth. Further, 43% of youth in this sample selected a multisexual identity that was not bisexual. Researchers should be more intentional about including a variety of response options, including queer and pansexual, in youth surveys of sexual orientation and identity.

The Trevor Project is dedicated to increasing multisexual visibility and improving the mental health and well-being of multisexual youth. Included in our efforts have been resources outlining ways in which individuals can support multisexual youth. Furthermore, we aimed to increase the visibility of the multisexual community through Trevor Staff’s celebration of Bi Awareness Week. Our research team will continue to release findings specific to multisexual youth and inform our services and advocacy efforts. Our crisis services team aims to provide all LGBTQ youth with high-quality care and has worked to create a diverse team of counselors that aligns with the demographics of the youth we serve, including multisexual staff and volunteers. Until all of us are able to recognize and support the needs and contributions of multisexual individuals to the LGBTQ community, we will continue to see data that reflects significant mental health challenges and suicide risk among the LGBTQ population.Download the Reseach Report

ABOUT THE TREVOR PROJECT

The Trevor Project is the world’s largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer & questioning (LGBTQ) young people. The Trevor Project offers a suite of 24/7 crisis intervention and suicide prevention programs, including TrevorLifeline, TrevorText, and TrevorChat as well as the world’s largest safe space social networking site for LGBTQ youth, TrevorSpace. Trevor also operates an education program with resources for youth-serving adults and organizations, an advocacy department fighting for pro-LGBTQ legislation and against anti-LGBTQ rhetoric/policy positions, and a research team to discover the most effective means to help young LGBTQ people in crisis and end suicide. If you or someone you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386 via chat www.TheTrevorProject.org/Help, or by texting START to 678-678.

This report is a collaborative effort from the following individuals at The Trevor Project:

Myeshia N Price, PhD

Senior Research Scientist

Carrie Davis, MSW

Chief Community Officer

Amy E. Green, PhD

Vice President of Research

Recommended Citation: Price, M. N., Green, A.E, & Davis, C. (2021). Multisexual Youth Mental Health: Risk and Protective Factors for Youth Who are Attracted to More than One Gender. New York, New York: The Trevor Project.

Media inquiries:

Kevin Wong

Vice President of Communications

[email protected]

212.695.8650 x407

Research-related inquiries:

Amy Green, PhD

Vice President of Research

[email protected]

310.271.8845 x242

REFERENCES

Almeida, J., Johnson, R. M., Corliss, H. L., Molnar, B. E., & Azrael, D. (2009). Emotional distress among LGBT youth: the influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 1001–1014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9

Birkett, M., Espelage, D., & Koenig, B. (2009). LGB and questioning students in schools: the moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 989-1000. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1

Callis, A. S. (2013) The black sheep of the pink flock: Labels, stigma, and bisexual identity, Journal of Bisexuality, 13(1), 82-105, doi: 10.1080/15299716.2013.755730

GLAAD Media Institute (2021) Where We Are On TV Report-2020. New York, New York: GLAAD Media Institute.

GLAAD Media Institute (2020) Studio Responsibility Index 2020. New York, New York: GLAAD Media Institute.

Green, A. E., Price-Feeney, M., Dorison, S. H., & Pick, C. J. (2020). Self-reported conversion efforts and suicidality among US LGBTQ youths and young Adults, 2018. American Journal of Public Health, 110(8), 1221–1227.

Johns, M.M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L.C., Zewditu, D., McManus, T., et al. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school student–19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR, 68(3), 65-71.

Johns, M.M., Lowry R., Haderxhanaj, L.T., et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Suppl, 69,(Suppl-1):19–27.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697.

O’Brien, K.H.M., Putney, J.M., Hebert, N.W., Falk, A.M., & Aguinaldo, L.D. (2016). Sexual and gender minority youth suicide: Understanding subgroup differences to inform interventions. LGBT Health, 3(4), 248-251.

Ochs, R. (2014, January 7). Bisexual: A few quotes from Robyn Ochs. Robyn Ochs. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://robynochs.com/bisexual/ .

Saewyc, E., Homma, Y., Skay, C. L., Bearinger, L., Resnick, M. D., & Reis, E. (2009). Protective factors in the lives of bisexual adolescents in North America. American Journal of Public Health, 99(1), 110-7.

Stettler, N. M., & Katz, L. F. (2017). Minority Stress, Emotion Regulation, and the Parenting of Sexual-Minority Youth. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 13(4), 380-400. doi:10.1080/1550428X.2016.1268551

The Trevor Project. (2019). Research Brief: Bisexual Youth Experience. New York, New York: The Trevor Project.

The Trevor Project. (2020). 2020 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. New York, New York: The Trevor Project.

The Trevor Project. (2020). How to Support Bisexual Youth: Ways to Care for Young People Who Are Attracted to More Than One Gender. New York, New York: The Trevor Project. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/How-to-Support-Bisexual-Youth.pdf

The Trevor Project. (2020). Trevor’s Bi Staff Commemorate Bi Awareness Week. New York, New York: The Trevor Project. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/2020/09/23/trevors-bi-staff-commemorate-bi-awareness-week/

Underwood, J. M., Brener, N., Thornton, J., Harris, W. A., Bryan, L. N., Shanklin, S. L., Deputy, N., Roberts, A. M., Queen, B., & Chyen, D. (2020). Overview and methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System — United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 1.