Background

LGBTQ young people experience significantly greater rates of both eating disorders and attempting suicide compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Johns et al., 2020; Parker & Harriger, 2020). Among the broader population of U.S. adults, those with a history of an eating disorder were found to have nearly 5–6 times greater odds of attempting suicide compared to those who have never had an eating disorder (Udo et al., 2019). In alignment with the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), past studies have found higher rates of eating disorders and suicide risk among LGBTQ individuals to be related to experiences of bullying and discrimination, as well as internalized stigma based on their LGBTQ identity and the concealment of their LGBTQ identity (Parker & Harriger, 2020). Additionally, previous research indicates that particular subgroups of the LGBTQ community, such as those who are transgender or nonbinary, may be at greater risk for eating disorders (Nagata et al., 2020). A review of disordered eating among transgender individuals found that body dissatisfaction is a common stressor and places some transgender individuals at greater risk for disordered eating (Jones et al., 2015). However, less is known about eating disorders among LGBTQ youth, particularly those who are transgender or nonbinary, or youth of color. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief examines eating disorders among LGBTQ youth, including which particular subgroups of LGBTQ youth report the highest rates of eating disorders and how eating disorders relate to suicide attempts among LGBTQ youth.

Results

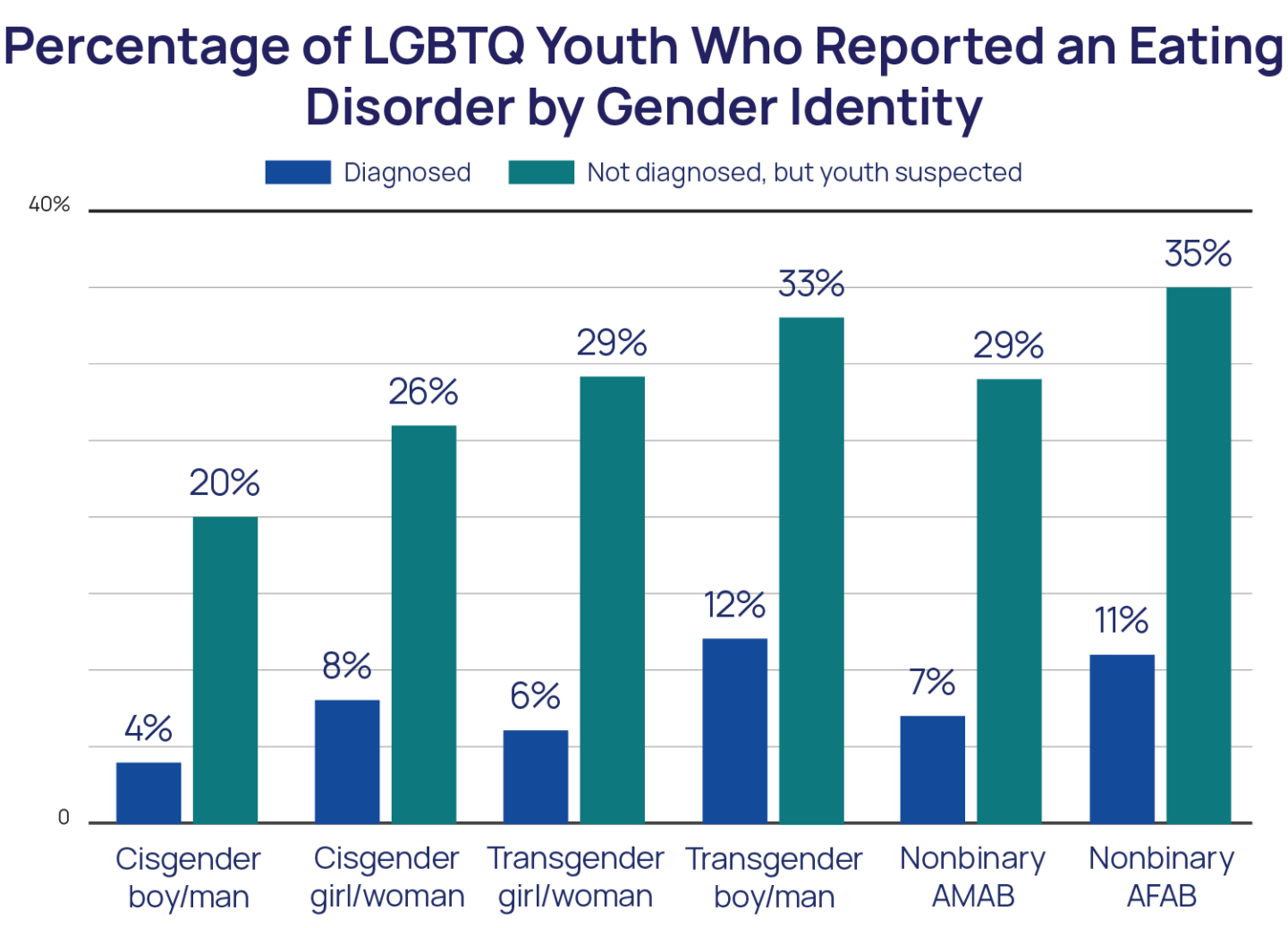

Overall, 9% of LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 stated that they have been diagnosed with an eating disorder, with an additional 29% stating they haven’t ever been diagnosed but suspect that they might have an eating disorder. Cisgender LGBQ boys/men reported the lowest rates of both being diagnosed with or suspecting they have an eating disorder. Transgender boys/men and nonbinary youth assigned female at birth (AFAB) had the highest rates of both being diagnosed with and suspecting they have an eating disorder. Cisgender girls/women, transgender girls/women, and nonbinary youth assigned male at birth (AMAB) had similar rates of being diagnosed with or suspecting they have an eating disorder.

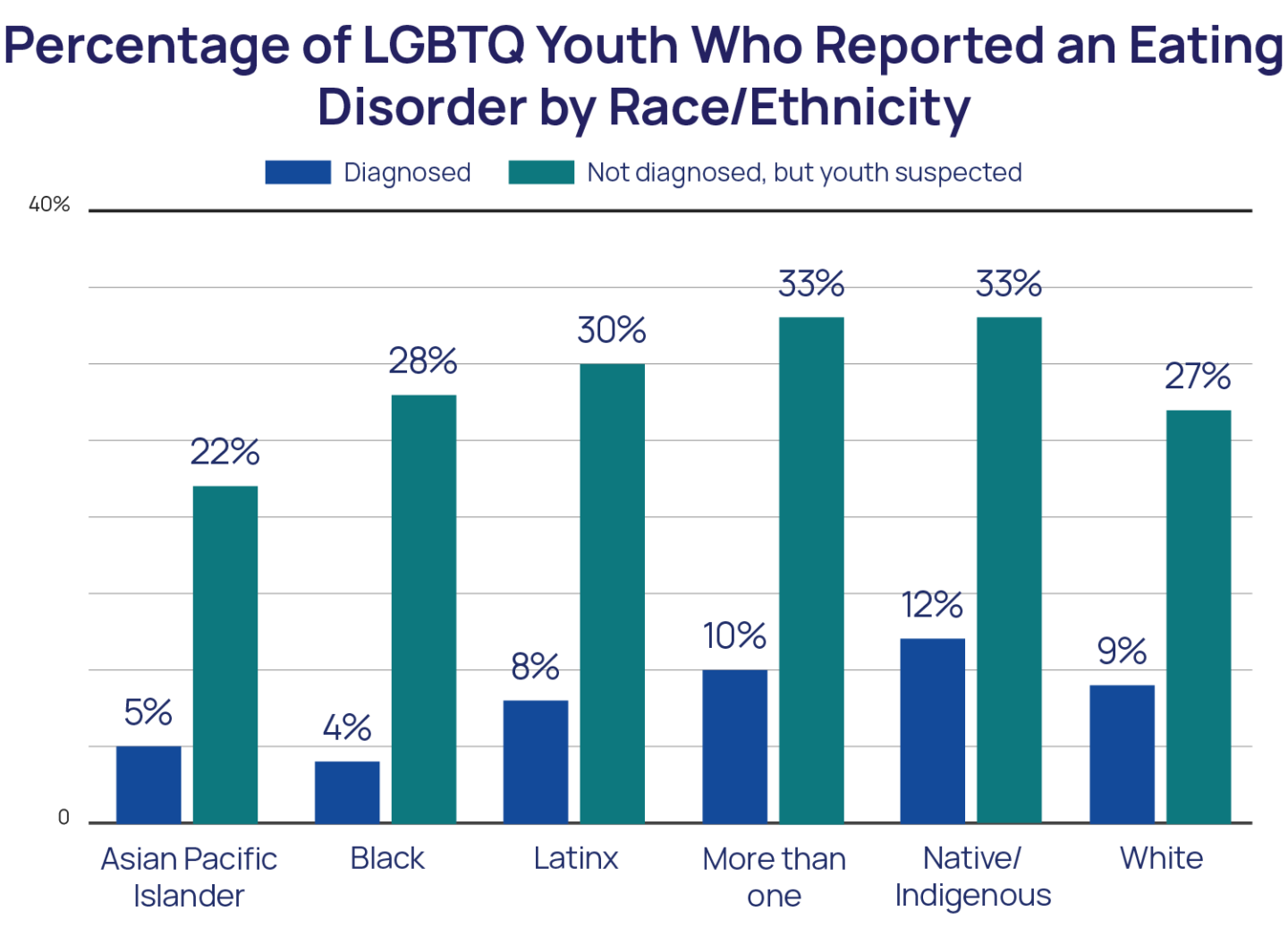

LGBTQ youth who are Native/Indigenous (12%) or Multiracial (10%) reported the highest rates of being diagnosed with an eating disorder, with an additional third (33%) of both groups suspecting they have an eating disorder. LGBTQ youth who are Asian Pacific Islander (5%) or Black (4%) reported the lowest rates of being diagnosed with an eating disorder. However, Black LGBTQ youth reported comparable rates of suspecting they have an eating disorder to White LGBTQ youth (28% Black vs. 27% White), despite White LGBTQ youth being diagnosed at more than twice the rate of Black LGBTQ youth (9% White vs. 4% Black).

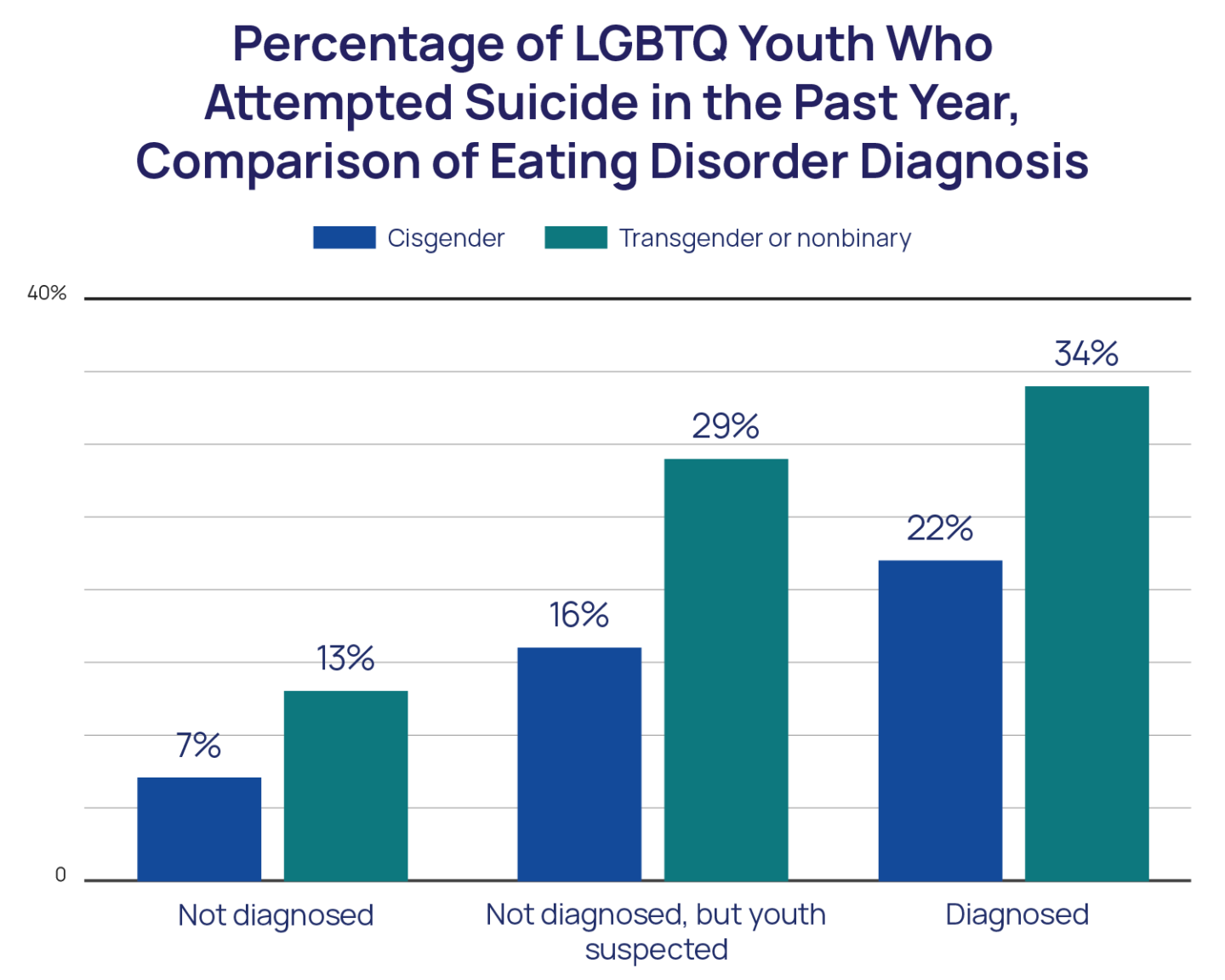

LGBTQ youth who have ever been diagnosed with an eating disorder had nearly four times (aOR=3.94) greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year compared to those who have never suspected nor had an eating disorder diagnosis. Suicide risk is also higher among those who suspected they had an eating disorder, despite never being diagnosed. These youth reported more than two times (aOR=2.38) greater odds of a suicide attempt in the past year compared to those who have never suspected they had an eating disorder. Although transgender and nonbinary youth reported higher rates of attempting suicide than cisgender youth overall, the strength of the relationship between eating disorder diagnosis and attempting suicide was similar for both cisgender LGBQ and transgender and nonbinary youth.

Methodology

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between October and December 2020 of 34,759 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. To assess self-reported eating disorders, youth were asked, “Have you ever been diagnosed as having an eating disorder?” with response options of 1) No, 2) No, but I think I might have one, and 3) Yes. Our item on attempting suicide in the past 12 months was taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). An adjusted logistic regression model was conducted to determine the association between eating disorder diagnosis and a past-year suicide attempt while controlling for age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual identity.

Looking Ahead

In alignment with results on studies of LGBTQ adults, our data showed that LGBTQ young people reported being diagnosed with an eating disorder at higher rates than those found in previous general U.S. population studies of lifetime prevalence for both adolescents ages 13–18 (3%; Swanson et al., 2011) and young adults ages 18–29 (5%; Hudson et al., 2007). Rates of eating disorders were even greater for transgender and nonbinary youth – particularly among transgender boys/men and nonbinary youth assigned female at birth. Multiracial and Native/Indigenous LGBTQ youth also had high rates of suspecting or being diagnosed with an eating disorder. Further, Black LGBTQ youth suspected they had an eating disorder at four times the rate of actually being diagnosed. The relationship between eating disorders and suicide risk in LGBTQ youth suggests providers must do more to close the gap between youth suspecting they have an eating disorder and receiving a clinical diagnosis in order to receive care. Healthcare providers working with LGBTQ youth should routinely assess risk for potential mental health concerns such as eating disorders and suicidal ideation. To create an environment in which youth feel more comfortable disclosing to healthcare professionals, healthcare organizations and training programs should focus on developing and maintaining high levels of provider cultural competence regarding all aspects of youth identity, including their sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity. Further, there is a need for greater attention to cultural competencies in the assessment and treatment of eating disorders, particularly regarding ways presentations and underlying causes may vary based on gender identity and race/ethnicity.

Given that previous research has found significant relationships between minority stress and both eating disorders and suicide risk, there is a need to focus on policies and practices that confront LGBTQ-based victimization and aim to reduce minority stress. This can include the creation of safe and supportive school environments, the enactment of anti-discrimination policies, and increased access to gender-affirming care for transgender and nonbinary youth. By reducing minority stress and improving access to culturally competent and affirming care, LGBTQ youth’s risk for both eating disorders and suicide can be reduced.

The Trevor Project is committed to finding ways for all LGBTQ youth to feel safe and supported. Our 24/7 crisis services connect youth with culturally competent and affirming adults, and our TrevorSpace platform connects youth with supportive peers. Further, Trevor’s research, advocacy, and education teams are focused on using data, policies, and education to enhance the ability of youth-serving professionals to understand and address their mental health needs.

References

- Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope Jr, H. G., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348-358.

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students—Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 79(Suppl-1), 19–27.

- Jones, B. A., Haycraft, E., Murjan, S., & Arcelus, J. (2016). Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in trans people: A systematic review of the literature. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 81-94.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697.

- Nagata, J. M., Ganson, K. T., & Austin, S. B. (2020). Emerging trends in eating disorders among sexual and gender minorities. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(6), 562-567.

- Parker, L. L., & Harriger, J. A. (2020). Eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors in the LGBT population: a review of the literature. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8(1), 1-20.

- Swanson, S. A., Crow, S. J., Le Grange, D., Swendsen, J., & Merikangas, K. R. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 714-723.

- Udo, T., Bitley, S., & Grilo, C. M. (2019). Suicide attempts in US adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders. BMC medicine, 17(1), 1-13.

For more information, please contact: [email protected]

Suggested Citation:

The Trevor Project (2022). Research Brief: Eating Disorders among LGBTQ Youth. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/eating-disorders-among-lgbtq-youth-feb-2022/. Accessed on [Date Accessed].