Background

Each new year, it is common for individuals to make resolutions associated with a personal goal, such as losing weight (Norcross et al., 2002). Although weight-based resolutions can lead to healthy changes for some, other people may find that resolutions contribute to unhealthy weight-control behaviors or body dissatisfaction, which can be defined as having negative attitudes and evaluations about one’s body. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people often report higher rates of unhealthy weight control and eating behaviors, eating disorders (see our brief on Eating Disorders for more information), and body dissatisfaction compared to their straight, cisgender peers (Parker & Harriger, 2020). These issues are of particular concern for transgender and nonbinary youth, who report even higher rates of poor body esteem (Grossman & D’Augelli, 2007). That said, many transgender and nonbinary youth have also reported that their body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors are associated with transgender-specific experiences, such as gender dysphoria and attempts to change one’s body or secondary sex characteristics (e.g., breast growth, widening of hips) to better match their gender identity (Jones et al., 2016). Transgender and nonbinary youth also report improved body satisfaction after receiving gender-affirming medical care (Tordoff et al., 2022). While previous research has found that poor body esteem is associated with attempting suicide among transgender youth (Grossman & D’Augelli, 2007), findings have not been replicated with a large, national sample, and data among LGB youth remains limited. Using the Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief aims to fill these gaps, examining rates of body dissatisfaction and its relationship with suicidality among a diverse national sample of LGBTQ youth.

Results

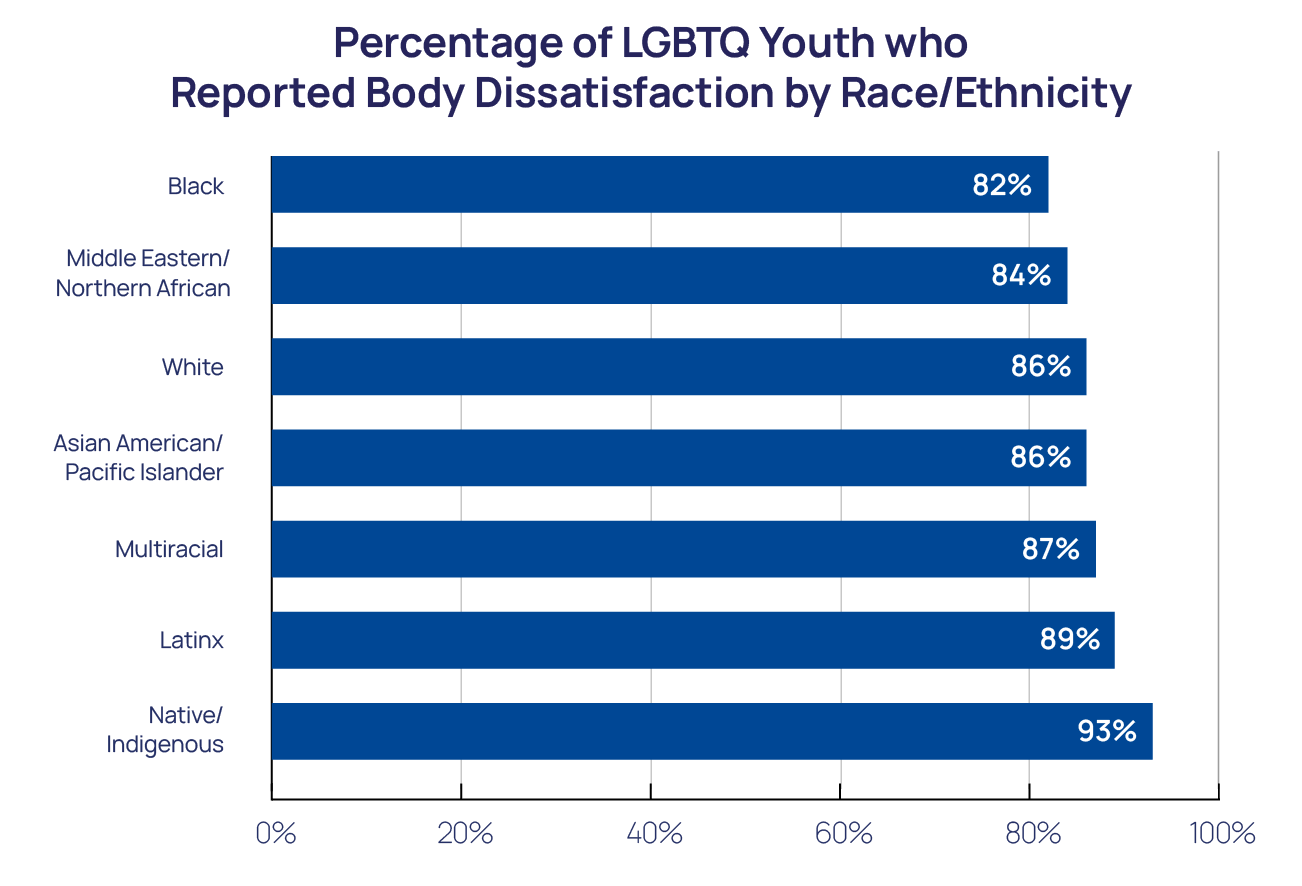

Nearly nine in ten (87%) LGBTQ youth reported being dissatisfied with their body. Although rates of body dissatisfaction were consistently high across racial groups, body dissatisfaction was highest among Native/Indigenous LGBTQ youth (93%) and lowest among Middle Eastern/Northern African (84%) and Black LGBTQ youth (83%). There were also high rates of body dissatisfaction across sexual orientations, with pansexual and questioning youth reporting the highest rates (91%), followed by queer (88%), asexual (87%), bisexual (86%), lesbian (85%), straight (83%), and gay (82%) youth. Furthermore, there were differences in body dissatisfaction between LGBTQ youth who were 18-24 years old (84%) compared to those who were 13-17 (88%).

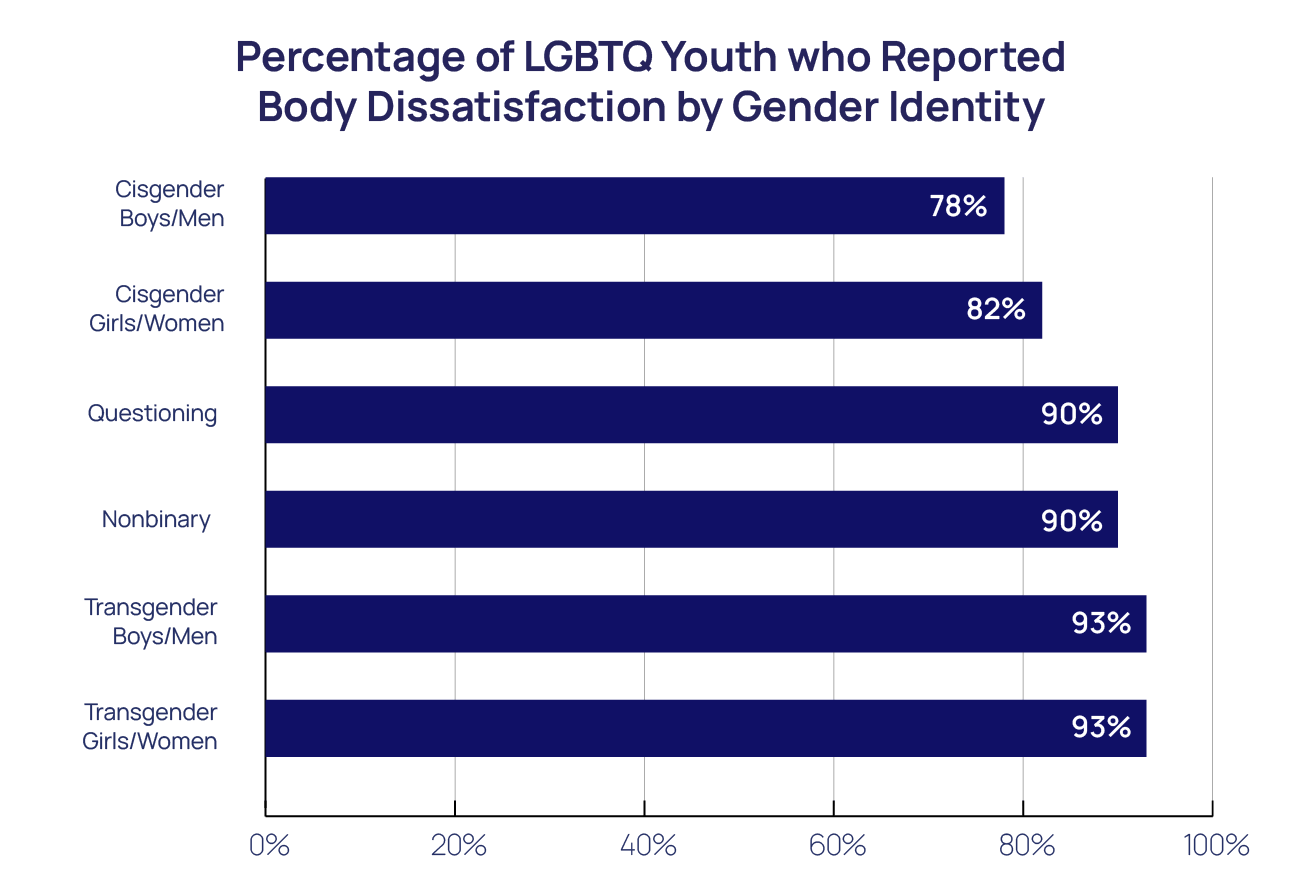

Rates of body dissatisfaction were higher among transgender and nonbinary youth (90%) compared to cisgender youth (80%). When looking at specific gender identities, transgender boys/men and girls/women reported the highest rates (93%), followed by questioning and nonbinary (90%) youth, cisgender girls/women (82%), and cisgender boys/men (78%). Nearly nine in ten (88%) transgender and nonbinary youth who were dissatisfied with their body reported that their body dissatisfaction was related to the difference between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth (i.e., gender-related body dissatisfaction). This included 41% of transgender and nonbinary youth who reported their dissatisfaction was gender-related to “a great extent” and 29% who reported “somewhat.”

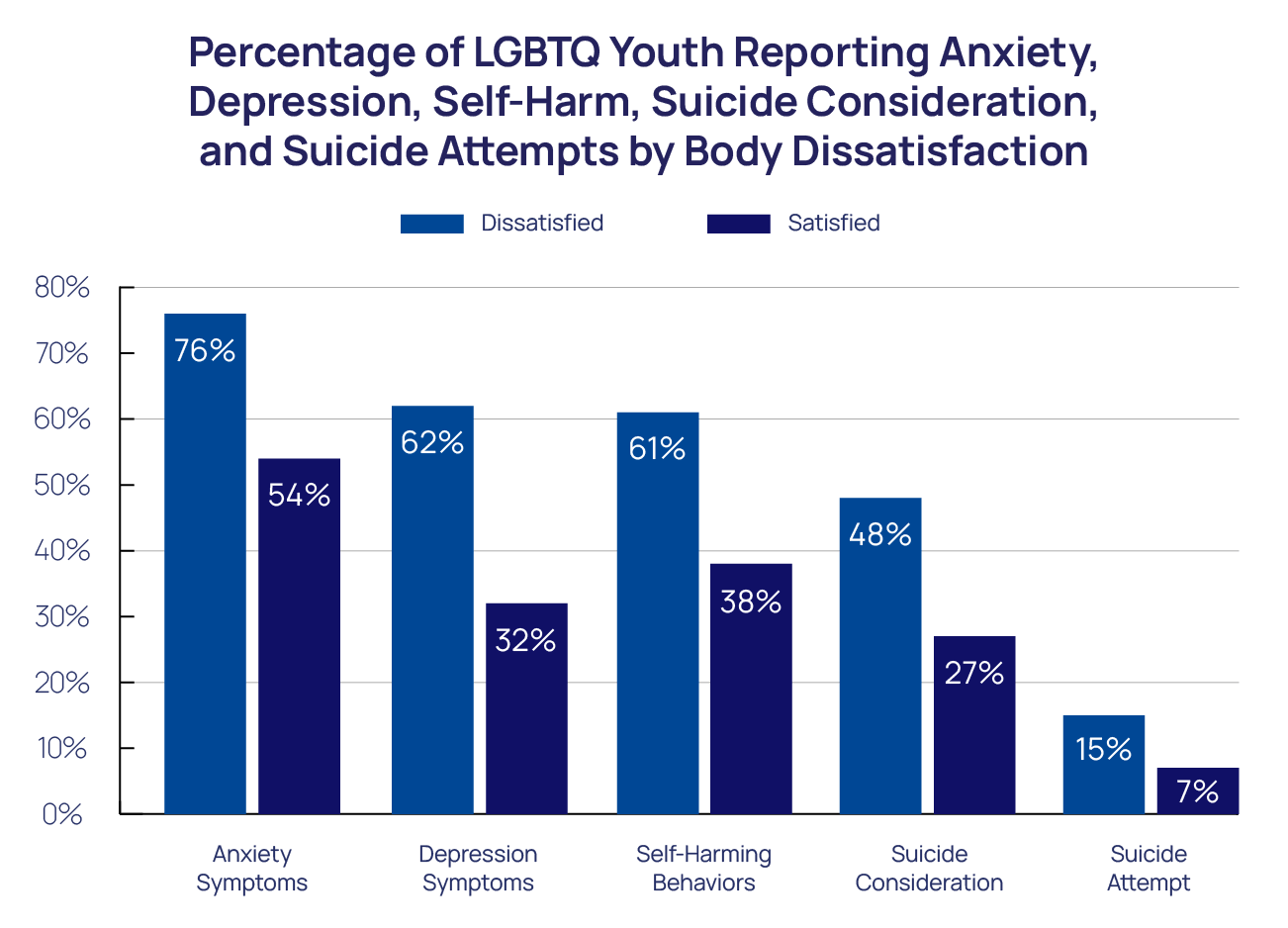

LGBTQ youth with body dissatisfaction reported higher rates of depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, self-harming behaviors, and considering suicide compared to LGBTQ youth with body satisfaction. LGBTQ youth who had body dissatisfaction reported higher rates of both recent depression symptoms (62%) and recent anxiety symptoms (76%) compared to youth with body satisfaction (32% and 54%, respectively). Similar findings existed for self-harming behaviors and seriously considering suicide. For LGBTQ youth who reported body dissatisfaction, 61% reported self-harm and 48% considered suicide, both in the last year. Comparatively, 38% of LGBTQ youth with body satisfaction reported self-harm, and 27% considered suicide.

LGBTQ youth with body dissatisfaction had twice the odds (aOR=1.96) of reporting a suicide attempt in the past year compared to LGBTQ youth with body satisfaction. LGBTQ youth who were dissatisfied with their body reported more than double the rate of attempting suicide in the past year (15%) compared to LGBTQ youth who were satisfied with their body (7%). Among transgender and nonbinary youth who were dissatisfied with their body, one in five (20%) who expressed gender-related body dissatisfaction reported a suicide attempt in the last year, which was higher than the suicide attempt rate for transgender and nonbinary youth who did not express gender-related body dissatisfaction (16%).

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September and December 2021 of 33,993 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. To assess body satisfaction, youth were asked, “During the past 12 months, how satisfied have you been with the way your body looks?” Response options included: 1) Very dissatisfied; 2) Dissatisfied; 3) Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; 4) Satisfied; and, 5) Very satisfied. Respondents who selected “Satisfied” or “Very satisfied” were coded as “Satisfied,” and those that selected a “Very dissatisfied,” “Dissatisfied,” or “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied” were coded as “Dissatisfied” with their body. Youth who selected “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied” were included in the “Dissatisfied” category because they did not specifically report being satisfied with their body. Youth who identified as transgender or nonbinary and selected either being “Very dissatisfied” or “Dissatisfied” were asked a follow-up question: “To what extent are your feelings about your body related to the difference in your gender and sex assigned at birth?” Response options included: 1) Not at all; 2) A little bit; 3) Somewhat; and, 4) To a great extent. Those who selected anything other than “Not at all” were coded as having reported that their body dissatisfaction was related to the difference between their gender identity and assigned sex at birth (i.e, gender-related body dissatisfaction). Questions assessing past-year suicidality and self-harm were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020), and questions assessing anxiety and depression were taken from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2). Individuals who endorsed symptoms above the cut-off for the GAD-2 and PHQ-2 (>2) were considered to have anxiety and depression symptoms. Chi-square tests were used to examine differences between groups. Adjusted logistic regression models were run to determine the association between body dissatisfaction and attempting suicide in the past year, controlling for race, sex assigned at birth, gender and sexual identity, and socioeconomic status.

Looking Ahead

Similar to previous findings, our results show that the vast majority of LGBTQ youth struggle with body dissatisfaction across race, age, gender, and sexual orientation. Additionally, rates of body dissatisfaction are higher for transgender and nonbinary youth, often being attributed to gender-related body dissatisfaction. Compared to their peers, LGBTQ youth may face additional pressure for body ideals through LGBTQ community standards and monolithic media representations of LGBTQ people (Gordon et al., 2016), which could particularly impact LGBTQ youth of color, as they have historically been misrepresented in the media. Given that our findings illustrate an association between body dissatisfaction and attempting suicide, it is essential to prioritize methods of improving body satisfaction among LGBTQ youth.

Our results found that the majority of transgender and nonbinary youth reported that their body dissatisfaction was specifically gender-related. In line with previous research, this suggests that gender-affirming medical care (e.g., hormone replacement therapy, puberty blockers) can positively impact body satisfaction, and therefore, the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth.

Affirming conversations and curricula should focus on providing education that explores the importance of body acceptance and having a healthy lifestyle (e.g., eating well, exercising), rather than achieving a certain physical appearance. This may be especially true when the desired appearance is based on unrealistic standards or during the new year, when youth are often surrounded by body-based resolutions. Affirming mental health care (e.g., therapy, support groups) is another space where discussion of body image and esteem could occur, as many therapeutic techniques have been found to be effective in improving body image (Alleva et al., 2015). Including questions about body satisfaction during initial meetings or intakes is also strongly encouraged, given the prevalence of body dissatisfaction among LGBTQ youth. Finally, it is essential to focus on policy and societal change to promote acceptance and understanding of LGBTQ youth, which can have systemic impacts on LGBTQ youth health.

At the Trevor Project, we are committed to supporting LGBTQ youth in all forms. Our crisis services, which are available 24/7 via phone, chat, and text, connect youth with culturally competent and LGBTQ-affirming counselors. We also operate TrevorSpace, a safe space social networking site, that allows youth to connect with supportive peers. Additionally, The Trevor Project’s research, advocacy, and education teams are focused on advancing policy to support LGBTQ youth. We will continue to examine the experiences of LGBTQ youth to illuminate the unique issues they may face, as well as possible solutions.

References

- Alleva, J. M., Sheeran, P., Webb, T. L., Martijn, C., & Miles, E. (2015). A meta-analytic review of stand-alone interventions to improve body image. PLoS One, 10(9), e0139177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139177

- Gordon, A. R., Austin, S. B., Pantalone, D. W., Baker, A. M., Eiduson, R., & Rodgers, R. (2019). 81. Appearance ideals and eating disorders risk among LGBTQ college students: The being ourselves living in diverse bodies (BOLD) study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(2), S43–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.096

- Grossman, A. H., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2007). Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 37(5), 527–537. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

- Jones, B. A., Haycraft, E., Murjan, S., & Arcelus, J. 2016. Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in trans people: A systematic review of the literature. International Review of Psychiatry, 281(1), 81–94. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1089217

- Norcross, J. C., Mrykalo, M. S., & Blagys, M. D. (2002). Auld lang Syne: Success predictors, change processes, and self-reported outcomes of New Year’s resolvers and nonresolvers. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(4), 397–405. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1151

- Parker, L. L., & Harriger, J. A. (2020). Eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors in the LGBT population: A review of the literature. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00327-y

- Tordoff, D. M., Wanta, J. W., Collin, A., Stepney, C., Inwards-Breland, D. J., & Ahrens, K. (2022). Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e220978. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

For more information please contact: [email protected]