Background

Research consistently shows that LGBTQ+ young people report higher rates of mental health concerns in comparison to their non-LGBTQ+ peers (McDonald, 2018). Of note, much of this research does not specifically focus on the experiences of LGBTQ+ girls and young women. However, there is literature documenting high rates of mental health problems in this community (Grant et al., 2023; Rogers & Taliaferro, 2020; Taliaferro et al., 2017), pointing toward a need for mental health services in this particular subgroup. These rates are often due to experiences of minority stress (Meyer, 2003), or negative experiences associated with one’s LGBTQ+ identity. Poor mental health among LGBTQ+ girls and young women may stem from negative experiences from living at the intersection of anti-LGBTQ sentiment, patriarchy, white supremacy, classism, or ableism, especially for those with multiple marginalized identities (Bowleg, 2017). Furthermore, there is limited data on the differences in mental health and experiences among specific identities within LGBTQ+ girls and young women. Thus, little is known about the mental health and experiences of LGBTQ+ girls and young women, especially in regard to their demographics, mental health, and mental health care-related needs, which could address possible disparities. This brief will explore the demographics, mental health, and mental health care-related needs of 8,298 LGBTQ+ girls and young women, ages 13 to 24, using data from The Trevor Project’s 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People.

Results

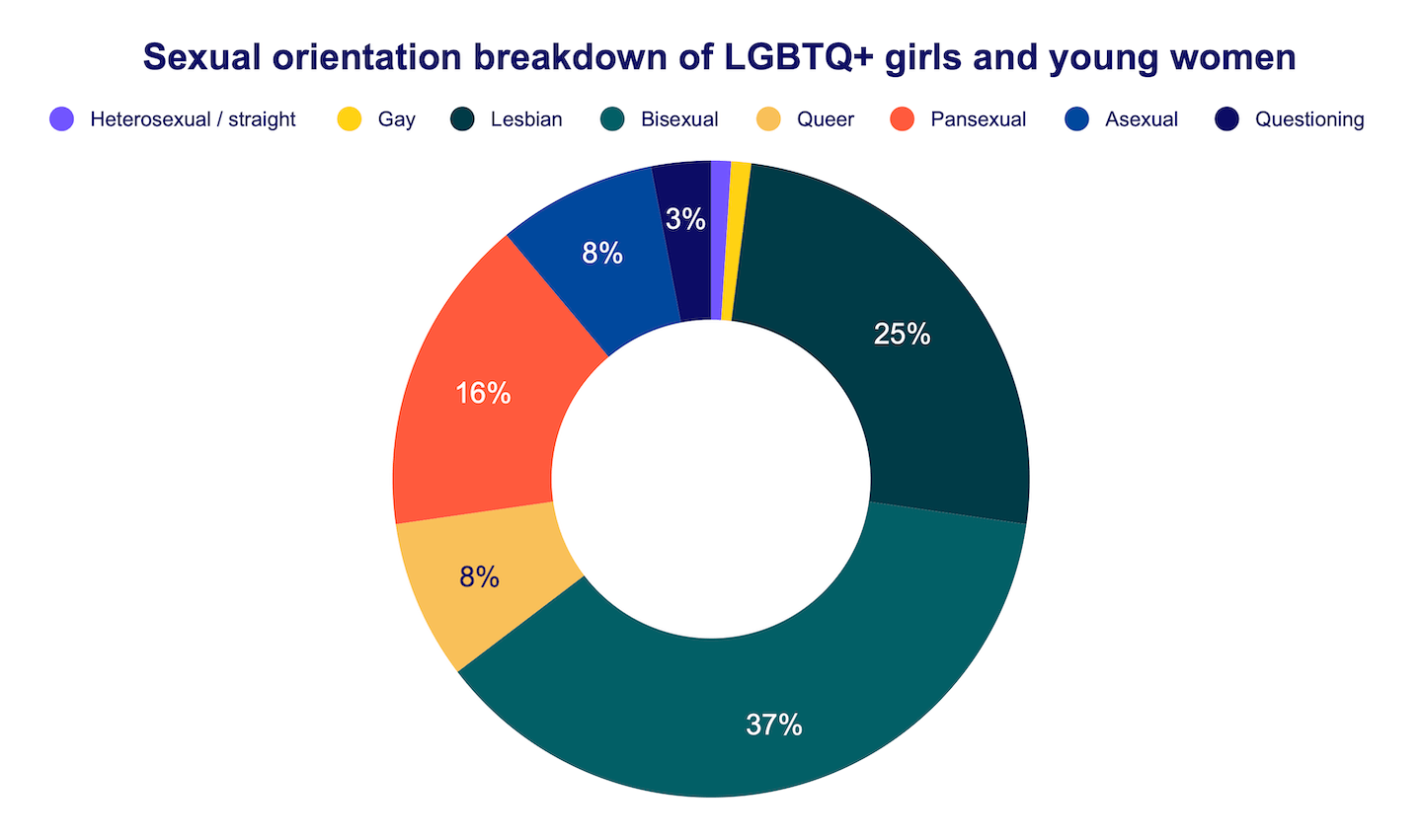

Demographics. Among the overall sample of LGBTQ+ girls and young women, 83% identified as cisgender and 17% as transgender. Regarding age, 59% were between the ages of 13-17 and 41% were between 18-24. For sexual orientation, 37% identified as bisexual, 25% as lesbian, 16% as pansexual, 8% as queer, 8% as asexual, 3% as questioning, 1% as gay, and 1% as straight or heterosexual (i.e., these participants were transgender women). Concerning race/ethnicity, 47% identified as White, 15% as Hispanic/Latinx, 7% as Asian American/Pacific Islander, 6% as Black/African American, 2% as Native/Indigenous, 1% as Middle Eastern/North African, and 23% as multiracial. Of note, cisgender participants more commonly identified as lesbian (26%), bisexual (39%), and queer (9%), while transgender participants more commonly reported being gay (2%), pansexual (29%), and questioning (6%), comparatively. White individuals tended to identify as lesbian (27%), pansexual (17%), and asexual (9%), compared to girls and women of color who identified with bisexual (39%) and queer (9%) identities. Younger participants (13-17) primarily identified as bisexual (38%), pansexual (17%), and questioning (5%), while the 18-24 group more frequently identified with queer (9%) and asexual (9%) labels.

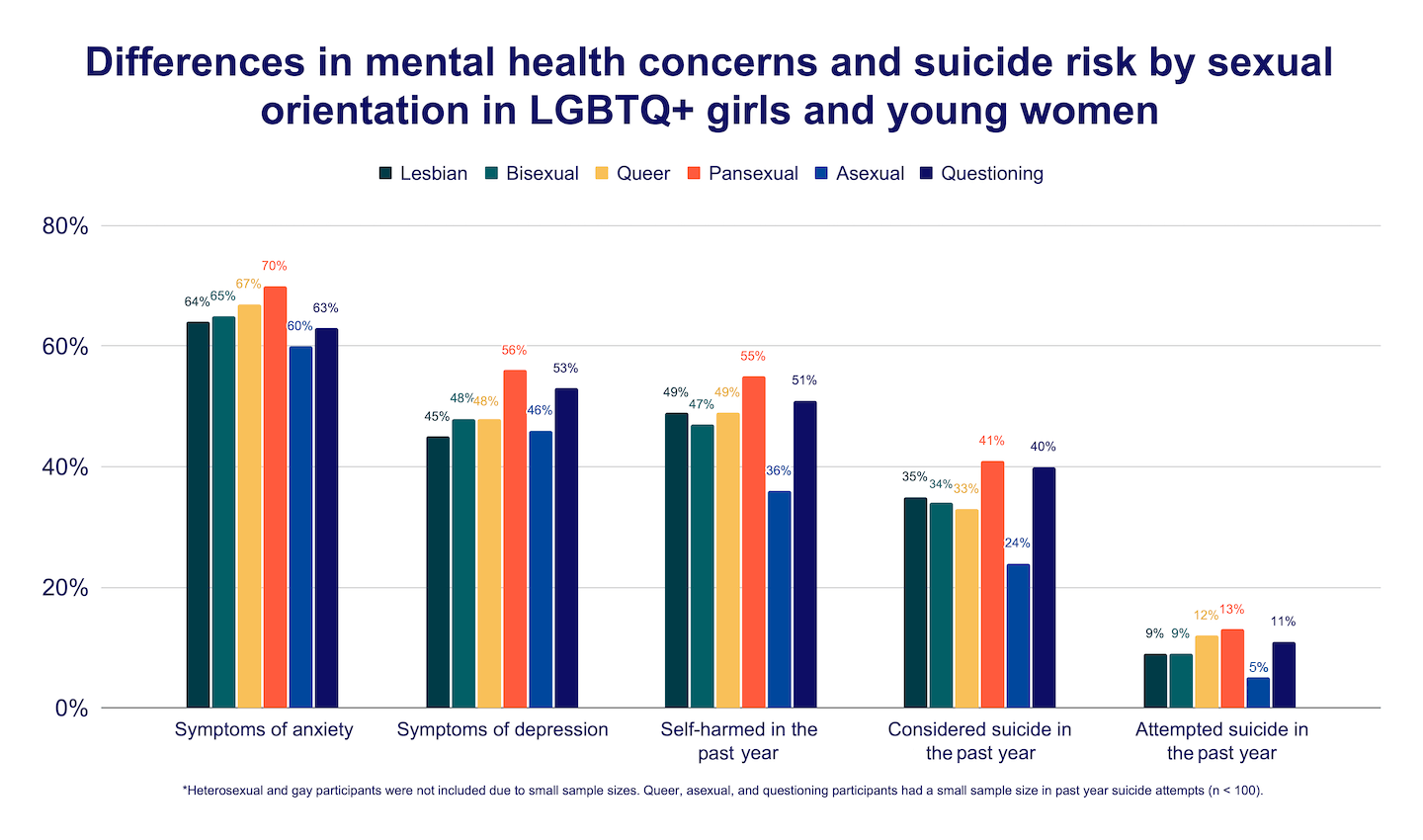

Mental Health. Among LGBTQ+ girls and young women, 65% reported symptoms of anxiety and 48% reported symptoms of depression in the past two weeks. In the past year, 48% reported self-harming, 34% considering suicide, and 10% attempting suicide. Compared to cisgender girls and women, transgender girls and women reported higher rates of all mental health concerns, as well as considering (48% vs. 31%) and attempting (16% vs. 8%) suicide in the past year. The chart below details the differences in mental health and suicidality by sexual orientation, with pansexual girls and young women consistently reporting the highest rates. Rates of mental health concerns and suicide risk for cisgender girls and women were consistently lower than individuals who identified as transgender.

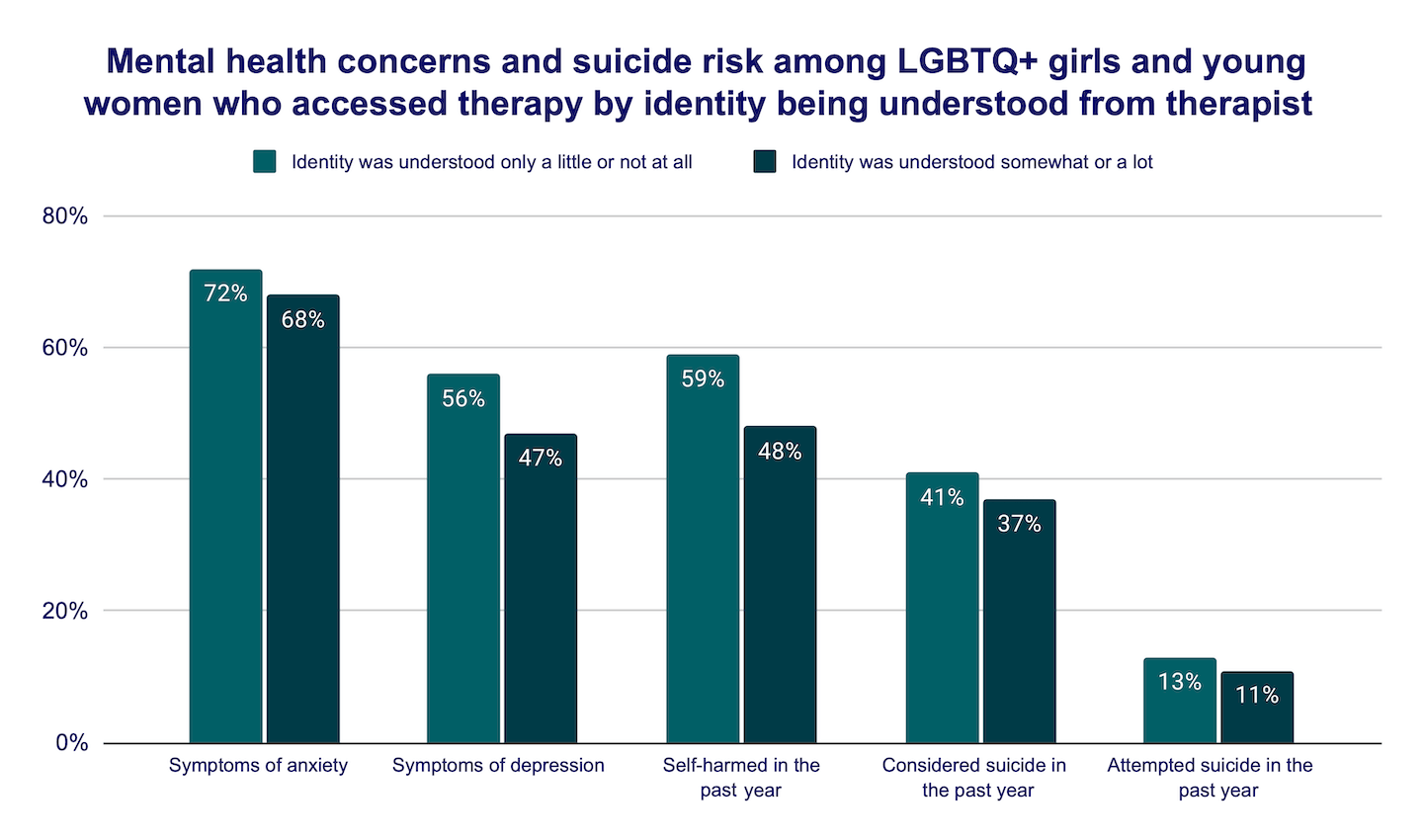

Mental Health Care Access. In total, 66% of LGBTQ+ girls and young women reported receiving mental health care in the past, with 58% of these individuals finding it helpful. Transgender girls and women were less likely to report that therapy was helpful (55%) when compared to cisgender girls and women (59%). In the past 12 months, 81% of LGBTQ+ girls and young women reported wanting mental health care, but of those, only 44% received it. For LGBTQ+ girls and young women, the primary barriers to accessing mental health care included fear of discussing mental health concerns (45%), not wanting to ask for parental permission (40%), affordability (36%), and fears of not being taken seriously (36%). For those who shared their LGBTQ+ identity with their therapist, 67% reported that the therapist understood their identity somewhat or a lot, while 33% felt it was understood only a little or not at all. Notably, transgender girls and women reported a higher rate of feeling understood (70%) when compared to cisgender girls and women (66%).

Of those who accessed therapy, individuals who felt their LGBTQ+ identity was understood somewhat or a lot reported lower rates of recent anxiety (68% vs. 72%) and depression (47% vs. 56%), as well as past-year self-harm (48% vs. 59%), considering suicide (37% vs. 41%), and attempting suicide (11% vs. 13%), compared to those who felt their identity was understood only a little or not at all. Feeling that their LGBTQ+ identity was understood by their therapist was also correlated with how helpful they perceived the therapy to be (Pearson correlation coefficient [r] = 0.88, p < 0.001). Specifically, LGBTQ+ girls and young women had over eight times the odds of finding therapy helpful if they felt their identity was at least somewhat understood by their therapist (aOR = 8.44, 95% CI = 7.07-10.08, p < 0.001) when compared to those who felt less understood. Those who had accessed therapy and found it helpful reported lower rates of recent anxiety (68% vs. 72%) and depression (47% vs. 56%), as well as past-year self-harm (48% vs. 59%), considering suicide (37% vs. 41%), and attempting suicide (11% vs. 13%), compared to those who did not find it helpful. More specifically, when therapy was helpful, LGBTQ+ girls and young women had 18% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 0.82, 95% CI = .68-.98, p < 0.05), compared to those who had therapy and did not find it helpful.

Methods

Data were collected through The Trevor Project’s 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People. In total, 28,524 LGBTQ+ young people between the ages of 13 to 24 were recruited via targeted ads on social media. Of these, a total of 8,298 participants identified as LGBTQ+ girls and young women and were included in this analysis.

Questions assessing past-year suicidality and self-harm were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Youth Risk Behavior Survey (CDC, 2023; Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020). Questions assessing symptoms of depression and anxiety were taken from the PHQ-2 and GAD-2, respectively (Löwe et al., 2005; Löwe et al., 2008). All other questions were created by The Trevor Project. Participants were asked, “Have you ever received psychological or emotional counseling from a counselor or mental health care professional?” and could respond “No,” “Yes, but it wasn’t helpful,” or “Yes, and it was helpful,” which was dichotomized for some analyses into “Not helpful” and “Helpful.” They were also asked, “In the past 12 months, have you wanted psychological or emotional counseling from a counselor or mental health professional?” and could respond “No,” “Yes, but I didn’t get it” or “Yes, and I got it,” which was also dichotomized for some analyses into “Did not receive” and “Received.” Additionally, they were asked, “Did you not see a counselor or mental health professional for any of the following reasons? Please select all that apply,” with a list of 20 possible reasons. Finally, they were asked, “How well did the counselor(s) or mental health care professional(s) you talked to understand LGBTQ identities?” and could respond “Not at all,” “A little bit,” “Somewhat,” and “A lot.” This was dichotomized for some analyses, combining “Not at all” with “A little” and “Somewhat” with “A lot.”

Chi-square tests were run to examine differences between groups. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was used to examine a correlation between therapy helpfulness and a therapist understanding their identity. All reported comparisons are statistically significant at least at p < 0.05. This means there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance. After checking assumptions, adjusted logistic regression models were run to examine the association between several variables (i.e., understanding LGBTQ+ identity and therapy helpfulness, therapy helpfulness and suicide), controlling for age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, and Census region.

Looking Ahead

LGBTQ+ girls and young women reported concerning rates of mental health concerns, with those who identified as multisexual and transgender reporting even higher rates of mental health problems and attempting suicide in the past year compared to their monosexual and cisgender peers. The vast majority of participants were interested in receiving mental health care, but most were unable to access it due to a variety of reasons ranging from financial struggles to internalized stigma surrounding their mental health. This is alarming, considering that mental health care — when LGBTQ+ centered and deemed helpful by LGBTQ+ girls and young women — was associated with lower rates of mental health concerns and significantly lower odds of a past-year suicide attempt. Thus, LGBTQ+ affirming mental health care can be lifesaving for LGBTQ+ youth.

Our findings reveal differences in the self-identification labels among LGBTQ+ girls and young women. For example, younger participants were more likely to identify as bisexual, pansexual, and questioning, while their older peers were more likely to identify as queer and asexual. Additionally, White youth were more likely to identify as lesbian, pansexual, and asexual, and participants of color identified more frequently as bisexual and queer. These variations highlight the diversity within LGBTQ+ girls and young women, underscoring that there are important differences to consider when attempting to understand a person’s identity. Learning about variations in self-identification among groups can assist individuals that work with LGBTQ+ girls and young women in effective communication about their identity or experiences when navigating the world. It can also help increase understanding about the ever-changing landscape of LGBTQ+ labels, or the words that youth use to describe their sexual orientation and gender identity.

Given these findings, it is essential that we work towards providing accessible and helpful mental health care for all those who need it. LGBTQ+ girls and young women who reported that their identity was understood by their therapist reported significantly lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year. Interestingly, in our sample, transgender girls and young women were more likely to report feeling understood by their therapist compared to cisgender girls and women, but less likely to find therapy helpful, which deserves further exploration. Mental health care providers working with LGBTQ+ girls and young women must be trained to support individuals who have had experiences stemming from the intersection of anti-LGBTQ sentiment and patriarchy. These experiences can include femme invisibility (i.e., feminine-presenting women presumed to be straight), harassment or violence for presenting one’s gender in non-traditional ways, or unequal pay. Specifically for transgender girls and women, this can also include being excluded from women’s spaces or celebrations of womanhood, such as International Women’s Day. Finally, intersectional analyses considering more demographic variables to better understand mental health care access is necessary.

At The Trevor Project, our Crisis Services team works 24/7 to help LGBTQ+ young people in crisis. We also focus on prevention efforts in order to limit the need for crisis resources in the future and reduce the risk of suicide for LGBTQ+ young people. We provide training to LGBTQ+ facing adults, including professionals who work with young girls and women (e.g., counselors, educators, nurses, social workers), to increase understanding of LGBTQ+ young people’s identities and provide guidance on trauma-informed suicide prevention efforts that are tailored to LGBTQ+ young girls and women. Additionally, Trevor’s Research team is committed to the ongoing dissemination of research that explores the experiences of LGBTQ+ young girls and women to prevent suicide in a vulnerable community, as well as improve their life experiences.

Recommended Citation: The Trevor Project. (2024). Mental Health and Access to Care for LGBTQ+ Girls and Young Women.

References

- Bowleg, L. (2017). Intersectionality: An Underutilized but Essential Theoretical Framework for Social Psychology. In B. Gough (Ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Social Psychology (pp. 507–531). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51018-1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs.

- Grant, J.M., & Alyasa, A.S., (2023). “We never give up the fight”: A report of the national LGBTQ+ women’s community survey. https://lalgbtcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/LGBT-Womens-Survey-Full-2023.pdf

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., & Underwood, J. M. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 States and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3external

- Löwe, B., Decker, O., Müller, S., Brähler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46, 266–274. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40221654

- Löwe, B., Kroenke, K., & Gräfe, K. (2005). Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2), 163–171. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006

- McDonald, K. (2018). Social support and mental health in LGBTQ adolescents: A review of the literature. Issues in mental health nursing, 39(1), 16-29. DOI: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1398283

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Rogers, M. L., & Taliaferro, L. A. (2020). Self-Injurious thoughts and behaviors among sexual and gender minority youth: A systematic review of recent research. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12, 335-350. DOI: 10.1007/s11930-020-00295-z

- Taliaferro, L. A., Gloppen, K. M., Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Eisenberg, M. E. (2018). Depression and suicidality among bisexual youth: A nationally representative sample. Journal of LGBT youth, 15(1), 16-31. DOI: 10.1080/19361653.2017.1395306

For more information please contact: [email protected]