Background

Nearly 1% of young people ages 12 to 19 in the United States report being deaf or having experienced significant hearing loss (Lin et al., 2011). While “deaf” refers to people who are unable to hear, “Deaf” with a capital “D” refers to the community and culture developed by and for deaf people, largely around a shared sign language (Pudans-Smith et al., 2019). This Brief will use the term “Deaf*” to include all forms of Deafness: medical and non-medical perspectives, Hearing Impaired, DeafBlind, and others (Beams, N.D.). Although being Deaf* is considered a disability by the Americans with Disabilities Act (Americans With Disabilities Act, 1990), many Deaf* people do not consider it a disability but simply a way of existing and communicating which is marginalized by the larger society (Hoffmeister, 2007). “Audism” describes the systematic marginalization of Deaf* people through discrimination, bias, and exclusion (Eckert & Rowley, 2013). Just as anti-LGBTQ bias contributes to minority stress and impacts the mental health of LGBTQ people (Meyer, 2003), audism contributes to minority stress and poor mental health among Deaf* individuals (Beese & Tasker, 2021). Research has found that Deaf* adults and youth report higher rates of depression and anxiety than their hearing peers (van Eldik et al., 2004; Kvam et al., 2006; Kushalnagar et al., 2019). Deaf* youth who are also LGBTQ must navigate a host of challenges related to the intersection of their identities: navigating outness among a small, close-knit Deaf community, lack of American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation and access in LGBTQ spaces, lack of LGBTQ awareness in Deaf* spaces, and others (Miller & Clark, 2020). However, many Deaf* LGBTQ people also report feeling welcomed and included as LGBTQ people in their Deaf communities, and that the intersection of their Deaf* and LGBTQ identities is a source of social connection, support, and community (Michaels & Gorman, 2020). This lack of representation in both communities extends to research, where there is little scholarly work on the mental health of youth who are both LGBTQ and Deaf*. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2020 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, this brief seeks to fill that gap by examining mental health and suicide risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) youth who are Deaf*.

Results

Overall, 5% of LGBTQ youth reported experiencing deafness or serious difficulty hearing. Only 36% of the youth who reported experiencing deafness or serious difficulty hearing also reported that they identified as a person with a disability. Deaf* LGBTQ youth had significantly higher rates of reporting that they struggled or were unable to meet their basic needs (25%) compared to LGBTQ youth who were not Deaf* (14%).

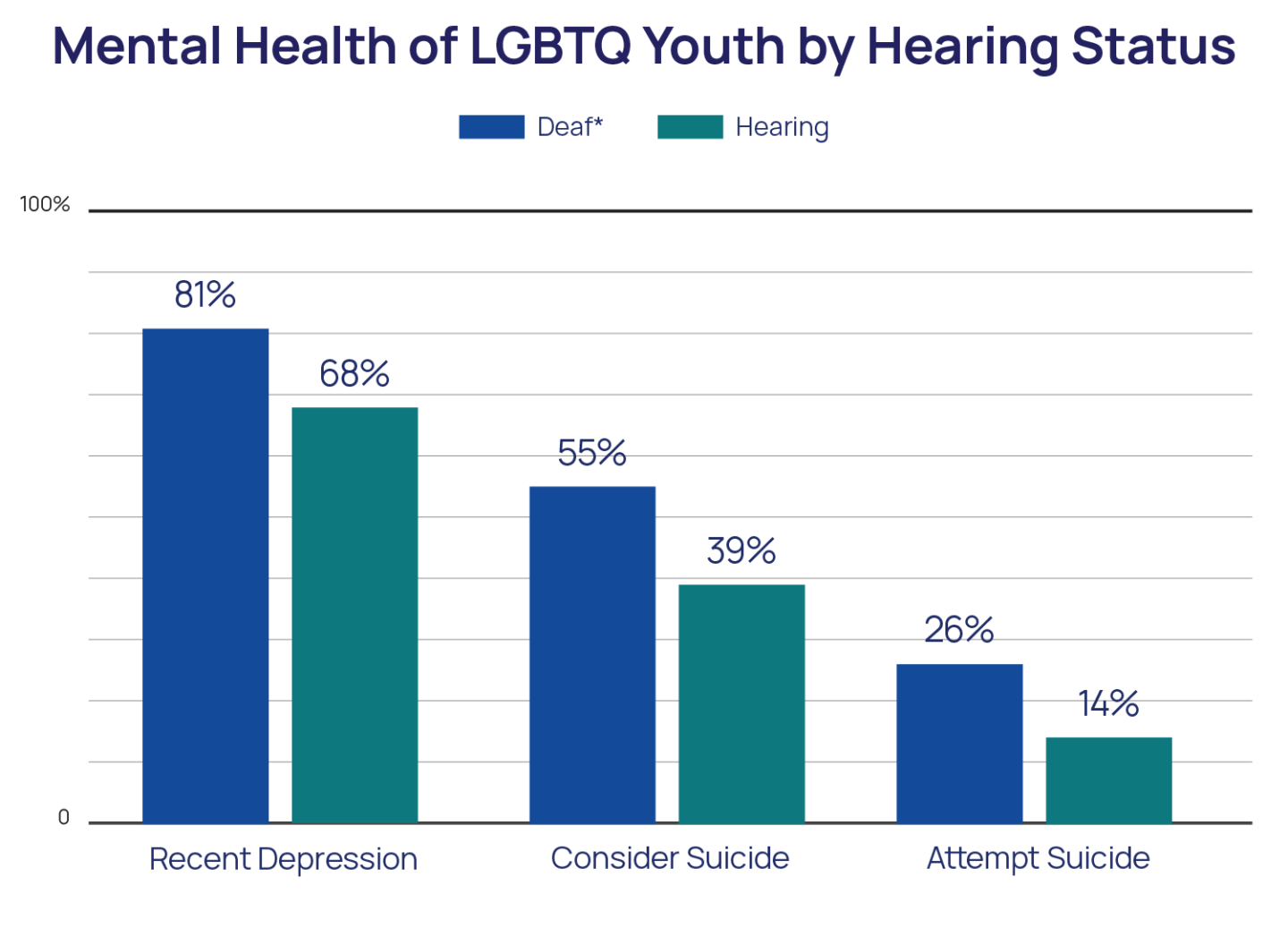

Deaf* LGBTQ youth reported significantly higher odds of symptoms of depression in the last two weeks (aOR = 1.70), considering suicide in the last year (aOR = 1.61), or attempting suicide in the last year (aOR = 1.88). Overall, 81% of Deaf* LGBTQ youth reported recent depression, compared to 68% of hearing LGBTQ youth. Further, 55% of Deaf* LGBTQ youth reported seriously considering suicide in the last year, and 26% reported attempting suicide in the last year, compared to 39% and 14% of hearing LGBTQ youth respectively.

Deaf* LGBTQ youth reported significantly higher rates of discrimination in the last year due to their sexual orientation or gender identity (59%), compared to their hearing peers (43%). Deaf* youth who reported discrimination due to their sexual orientation or gender identity in the last year reported nearly twice the odds of considering suicide in the last year (aOR = 1.90), and over twice the odds of attempting suicide in the last year (aOR = 2.42).

Deaf* LGBTQ youth who reported high levels of family support reported approximately half the odds of considering suicide (aOR = 0.56) or attempting suicide (aOR = 0.49) in the last year. Deaf* youth were less likely to report having high levels of family support for their sexual orientation or gender identity (35%) compared to their hearing peers (27%).

Methods

Data was collected from an online survey conducted between December 2019 and March 2020 of 40,001 LGBTQ youth recruited via targeted ads on social media. Respondents were identified to be Deaf* if they reported that they experienced “Deafness or serious difficulty hearing.” Their identification as a person with a disability was measured by asking “Do you identify as a person with a disability?” Questions assessing recent depression were taken from the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) (Richardson et al., 2010). Questions assessing suicide risk (“During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”, “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”) were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Adjusted logistic regression models controlled for age, race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual identity, and socioeconomic status.

Looking Ahead

Deaf* LGBTQ youth reported higher odds of recent depression, considering suicide, or attempting suicide in the last year. These findings align with larger trends (van Eldik et al., 2004; Kvam et al., 2006; Kushalnagar et al., 2019) and highlight the need for mental health services that are culturally competent for both the LGBTQ and Deaf* communities. Mental health care providers should be prepared to serve clients in ways that both affirm their LGBTQ identities and are accessible to their needs as Deaf* clients. Deaf* LGBTQ youth also reported higher rates of discrimination due to their sexual orientation or gender identity, and experiencing discrimination was also associated with higher odds of considering or attempting suicide in the last year. While Deaf* LGBTQ youth were less likely to report high levels of family support for their LGBTQ identity, high levels of family support were associated with decreased odds of considering or attempting suicide in the last year. These data demonstrate the need for more Deaf* inclusion in family support programming for LGBTQ youth and their families. LGBTQ spaces and organizations must be more accessible to Deaf* community members, including having ASL interpretation at community events, training staff to serve Deaf* people, explicitly mentioning support for Deaf* people on websites and promotional materials, hiring Deaf* staff, participating in Deaf* advocacy, building relationships with organizations that serve Deaf* people, and promoting the voices of Deaf* LGBTQ people.

It is important to note the limitations of this data. Our survey did not include more detailed questions about youths’ experiences as Deaf* individuals, such as whether they use ASL, whether they identify as a member of the Deaf community, or what kind of education they have received. Future research should capture more information about Deaf* LGBTQ youth’s experience navigating the intersection of these identities, and the challenges raised by audism and anti-LGBTQ bias.

The Trevor Project is dedicated to supporting Deaf* LGBTQ youth. Our Crisis Services are available 24/7 to any LGBTQ youth in need. Our text and chat services are accessible to Deaf* youth using text-based communication, and our phone Lifeline can be accessed with the support of an interpreter or voice-to-text/text-to-voice service. Our Media team has worked to add custom captions to our video content and will continue to add captions to all our social media content moving forward. We are also working to increase the accessibility of our Volunteer Training through captions, transcripts, and written directions. Finally, our Research Team will continue to explore risks and protective factors among LGBTQ youth to further understand and prevent suicide among this group.

References

- Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-336, 104 Stat. 328 (1990).

- Beams, D. (n.d.). Communication Considerations: Deaf Plus. Hands & Voices. Retrieved March 8, 2022, from https://www.handsandvoices.org/comcon/articles/deafplus.htm

- Beese, L. E., & Tasker, F. (2021). Toward an understanding of the experiences of deaf gay men: an interpretative phenomenological analysis to an intersectional view. Journal of Homosexuality, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.1940015

- Eckert, R. C. (2010). Toward a theory of deaf ethnos: deafnicity D/deaf (homaemon * homoglosson * homothreskon). Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 15(4), 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enq022

- Eckert, R. C., & Rowley, A. J. (2013). Audism: a theory and practice of audiocentric privilege. Humanity & Society, 37(2), 101–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597613481731

- Hoffmeister, R. J. (2007). Language and the deaf world: difference not disability. In M. E. Brisk & P. Mattai (Eds.), Language, Culture, and Community in Teacher Education (0 ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203857168

- Kvam, M. H., Loeb, M., & Tambs, K. (2006). Mental health in deaf adults: symptoms of anxiety and depression among hearing and deaf individuals. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 12(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enl015

- Kushalnagar, P., Reesman, J., Holcomb, T., & Ryan, C. (2019). Prevalence of anxiety or depression diagnosis in deaf adults. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 24(4), 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enz017

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Michaels, P., & Gorman, A. (2020). “Two communities, one family: experiences of young deaf LGBT+ people living in a minority within a minority.”, in young, disabled and LGBT+ voices, identities and intersections. In A. Toft & A. Franklin (Eds.), Young, Disabled and LGBT+ Voices, Identities and Intersections. Routledge.

- Miller, C. A., & Clark, K. A. (2020). Deaf and queer at the intersections: deaf LGBTQ people and communities. In C. A. Miller & K. A. Clark, Deaf Identities (pp. 305–335). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190887599.003.0013

- Pudans-Smith, K. K., Cue, K. R., Wolsey, J.-L. A., & Clark, M. D. (2019). To deaf or not to deaf: that is the question. Psychology, 10(15), 2091–2114. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2019.1015135

- Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1097–e1103.

- van Eldik, T., Treffers, Ph. D. A., Veerman, J. W., & Verhulst, F. C. (2004). Mental health problems of deaf dutch children as indicated by parents’ responses to the child behavior checklist. American Annals of the Deaf, 148(5), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2004.0002

Acknowledgements: The Trevor Project thanks Douglas Tapani for his time and expertise in reviewing this Brief.

For more information please contact: [email protected]

Suggested Citation:

The Trevor Project (2022). Research Brief: Mental Health of Deaf* LGBTQ Youth. Available at: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/mental-health-of-deaf-lgbtq-youth-mar-2022/. Accessed on [Date Accessed].