Background

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) young people have higher rates of suicide risk and victimization than their cisgender and straight peers (Johns et al., 2020). An affirming environment, including school, for LGBTQ young people can improve their mental health and reduce their risk of suicide (Hatzenbuehler 2011; Russel et al., 2018); however, 68% of LGBTQ students reported feeling unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression (Kosciw et al., 2022). Young people between the ages of 13 and 18 spend a significant portion of their waking hours at schools, making it imperative to examine how schools can create affirming environments for LGBTQ students in middle or high school. That said, it remains unclear what adults in these spaces can specifically do to make them more affirming for LGBTQ students. Building on our previous work showing that LGBTQ students who learn about suicide prevention or LGBTQ issues in school have lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year (The Trevor Project, 2021), this current study uses data from The Trevor Project’s 2023 National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People to explore the protectiveness associated with five school-related factors among LGBTQ middle and high school students: 1) learning about LGBTQ people and experiences in sex education, 2) learning about LGBTQ stories and people in history class, 3) having access to a gender-neutral bathroom, 4) the presence of an on-campus Gender and Sexuality Alliance or a Gay Straight Alliance (GSA), and 5) teachers who respect student’s pronouns.

Results

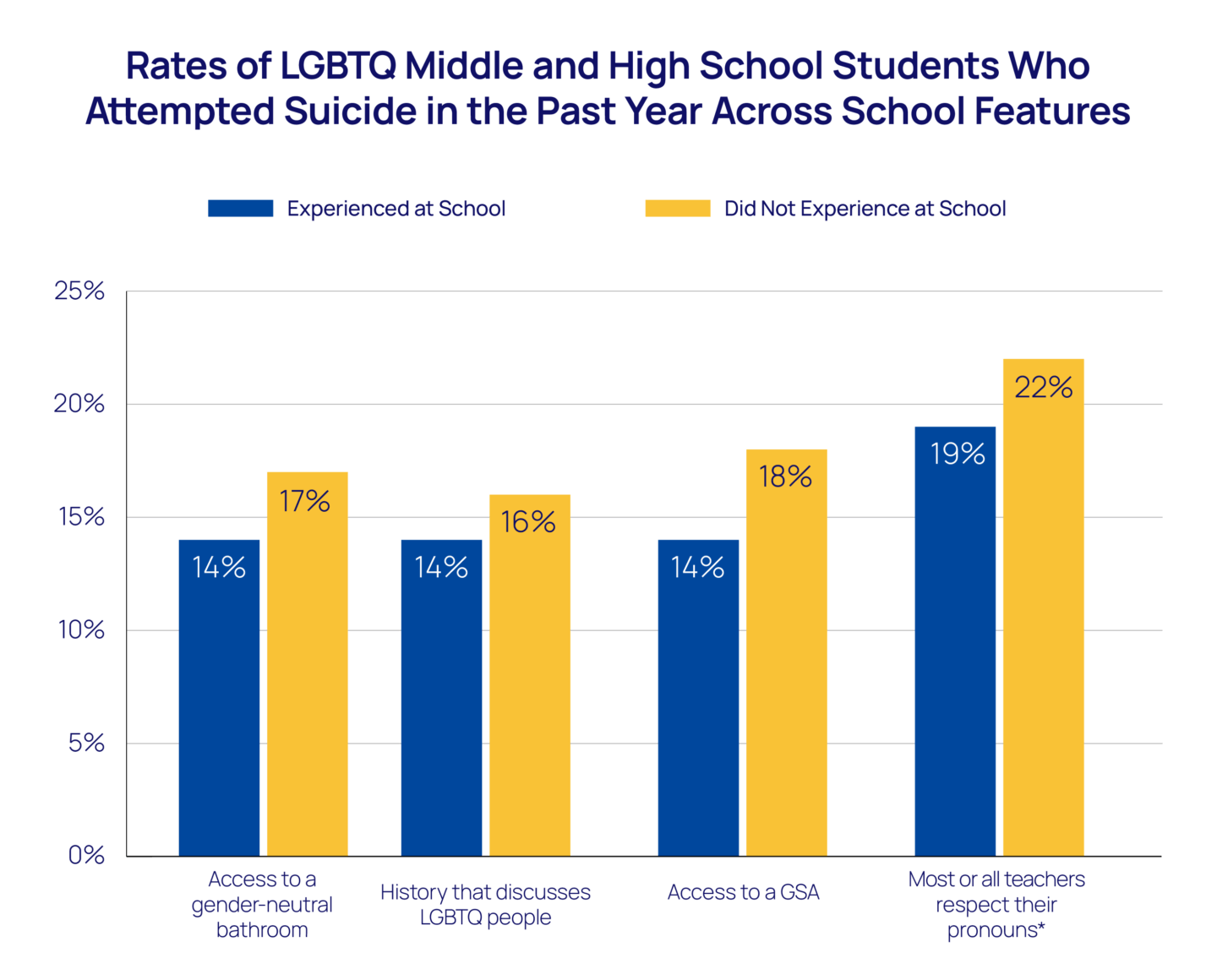

LGBTQ middle and high school students with access to at least one of these school-related protective factors had 26% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year. Specifically, 17% of LGBTQ middle and high school students who did not have access to gender-neutral bathrooms in school reported attempting suicide in the past year compared to 14% who did. Additionally, LGBTQ middle and high school students who were taught history that included LGBTQ stories and people reported lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year (14%) compared to those who were not (16%). Transgender and nonbinary middle and high school students who reported that most or all of their teachers respect their pronouns reported lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year (19%) compared to those who reported fewer teachers respected their pronouns (22%). Finally, LGBTQ middle and high school students with access to a GSA or similar club on campus reported lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year (14%) compared to those who did not (18%). Learning about LGBTQ experiences in sex education was not associated with significantly different rates of suicide attempts in the past year, but it was associated with lower rates of considering suicide in the past year. Overall, LGBTQ middle and high school students with at least one of these school-related protective factors had 26% lower odds of reporting a suicide attempt in the past year compared to LGBTQ middle and high school students who did not have any of these school-related protective factors (aOR=0.74, CI [0.67, 0.84], p < 0.01).

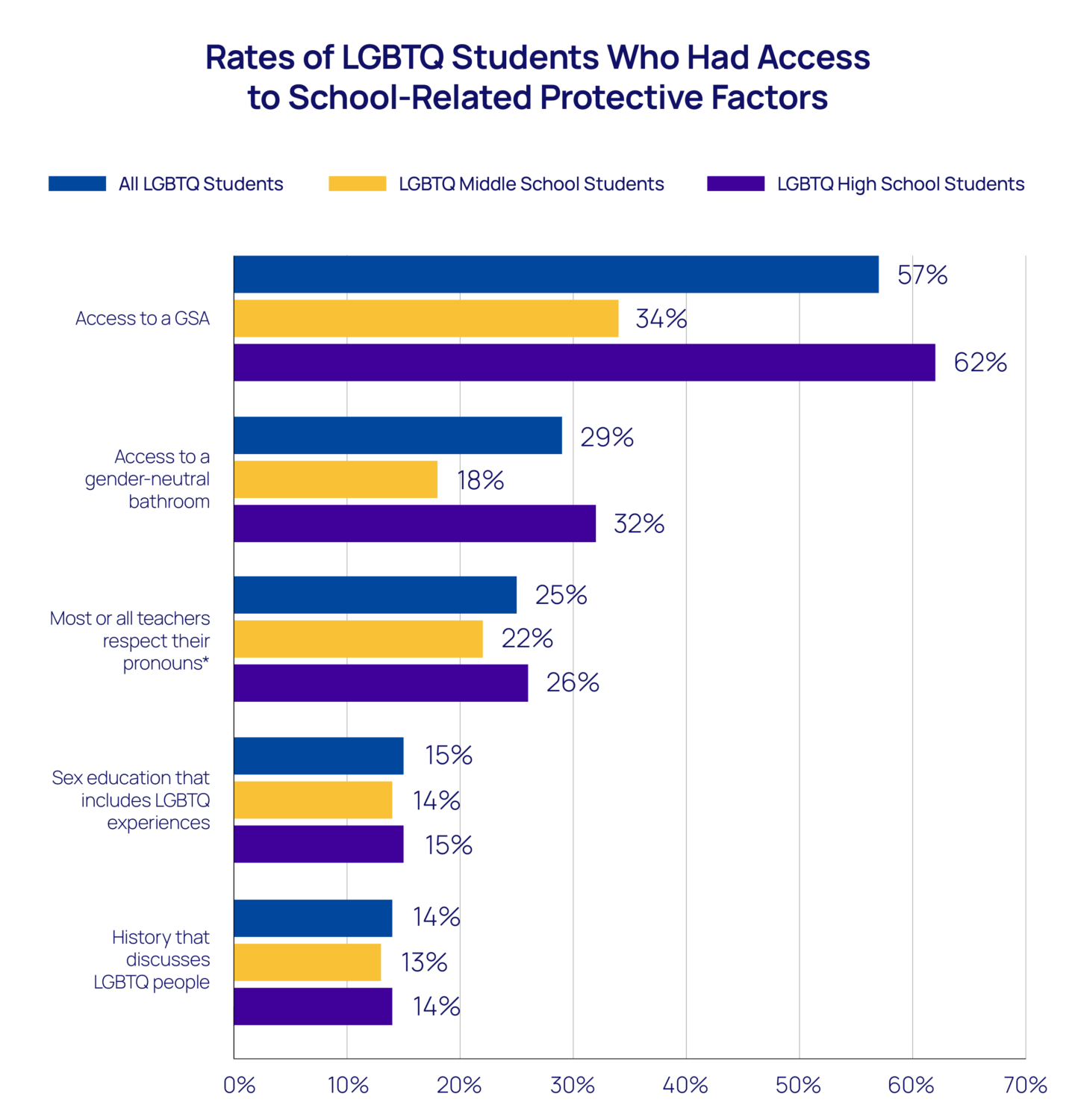

The majority of LGBTQ middle and high school students (70%) had access to at least one school-related protective factor. Among all LGBTQ students in middle school and high school, 57% attended a school with a GSA or similar club in the most recent school year, 29% had access to a gender-neutral bathroom, 15% were taught sex education that included discussions about LGBTQ people and experiences, and 14% were taught history that included LGBTQ stories and people. Additionally, 25% of transgender and nonbinary middle and high school students said most or all teachers respected their pronouns. That said, LGBTQ students in high school reported significantly higher rates of all of these school-related protective factors compared to their LGBTQ peers in middle school, with the exception of sex education that included discussions about LGBTQ people and experiences. Overall, 35% of LGBTQ students in middle and high school had access to only one of these protective factors, 36% had access to at least two, 14% had access to at least three of the protective factors, 4% had access to at least four, and only 1% of LGBTQ students in middle and high school had access to all five of the assessed protective factors.

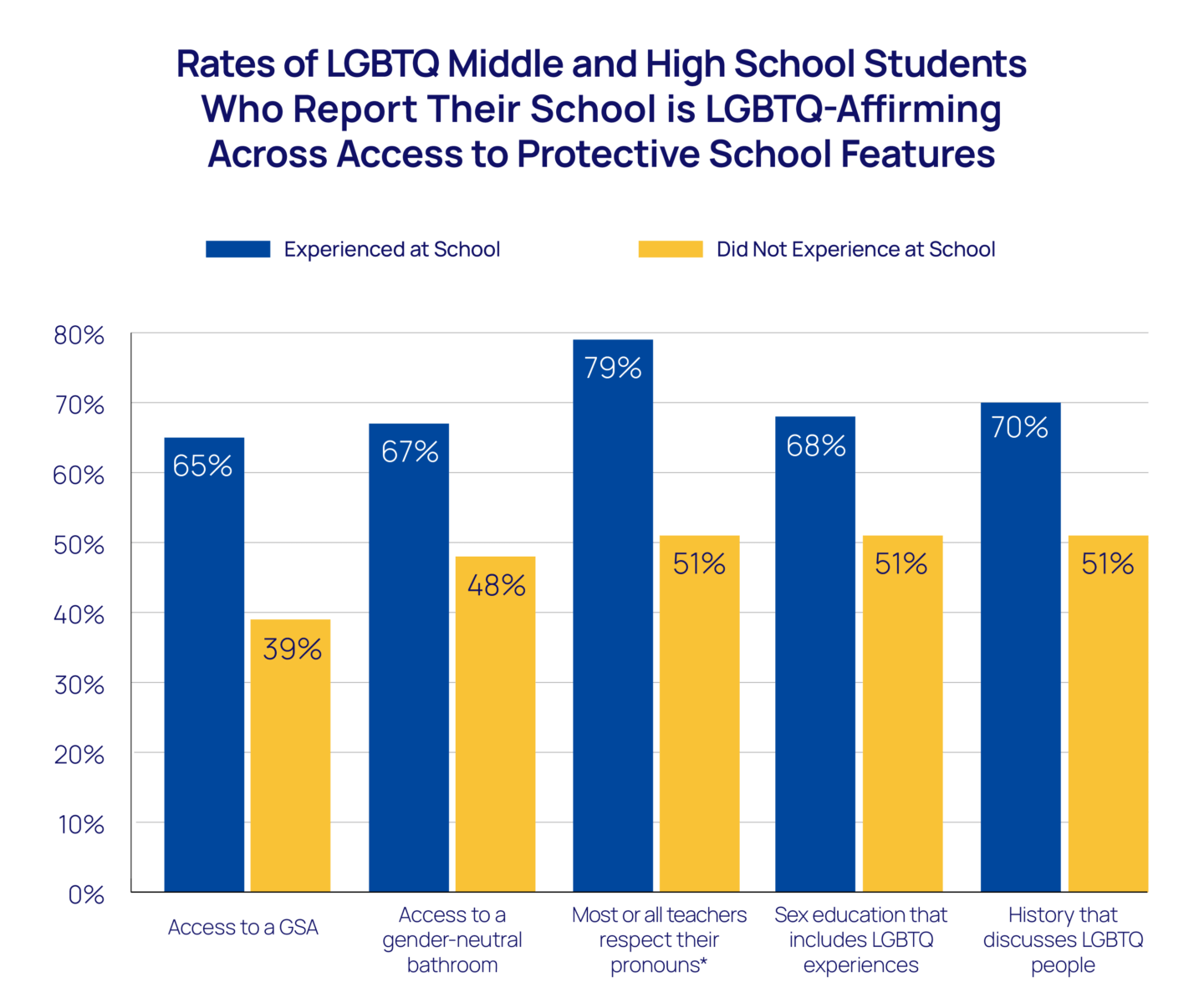

LGBTQ middle and high school students who had at least one of these school-related protective factors had three times higher odds of reporting their school as LGBTQ-affirming. Overall, 55% of LGBTQ middle and high school students reported that their school was LGBTQ-affirming. 65% of LGBTQ students in middle and high school who reported their school had a GSA or similar club in the past year reported their school was LGBTQ-affirming, compared to 39% when a GSA or similar club was not present. Two-thirds (67%) of LGBTQ students in middle and high school with a gender-neutral bathroom at school reported their school was LGBTQ-affirming compared to less than half (48%) of those who did not have a gender-neutral bathroom. When LGBTQ students in middle and high school were taught sex education that discussed LGBTQ people and experiences, 68% reported their school was LGBTQ-affirming compared to 51% who did not have sex education inclusive of LGBTQ people and experiences. The majority (80%) of transgender and nonbinary middle and high school students who reported that most or all of their teachers respected their pronouns said their school was LGBTQ-affirming compared to 51% of transgender and nonbinary students who reported their pronouns were respected by fewer teachers. Finally, when history that includes LGBTQ stories and people was taught, 70% of LGBTQ students in middle and high school reported their school as affirming compared to 51% when history that includes LGBTQ stories and people was not taught. Overall, when LGBTQ young people had at least one of these school-related protective factors, 62% reported their schools as LGBTQ- affirming compared to 34% who had none of these protective factors (aOR=3.15, 95% CI [2.85, 3.49], p < 0.01).

Methods

Data were collected from an online survey conducted between September 1 and December 12, 2022. Individuals between the ages of 13 and 24 who resided in the United States were recruited via targeted ads on social media. The sample for this brief was restricted to 15,791 young people who reported they were ages 13 to 18 and that they attended middle school or high school. The respondents were asked, “Have you ever learned about the following subjects in school?” Participants had the option to select any of the following which applied to them: “Suicide Prevention,” “Sex education that talks about LGBTQ people and experiences,” or “History that includes LGBTQ stories and people.” To determine information about students’ experiences with GSAs, young people were asked “Did the school that you attended during the most recent school year have a Gay/Straight Alliance (GSA) or another type of club that focuses on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) issues?” They could select from the response options “No,” “Yes,” “I am not sure what this is,” and “I know what this is, but do not know if my school had one.” Responses were dichotomized to compare those who answered “Yes” to any other selection. Participants were also asked, “How many of your teachers/professors respect your pronouns (as in, use the pronouns you want them to use for you)?” The response options were “None of them,” “A few of them,” “Some of them,” “A lot of them,” and “All or most of them,” which were dichotomized such that students who responded “All or most of them” were compared to all other students. Participants were also asked, “Is there a gender-neutral bathroom at your school?” to which they could respond, “No,” “Yes,” or “I don’t know.” The items for measuring considering and attempting suicide are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Chi-square tests were used to compare groups. Adjusted logistic regression controlling for age, Census Region, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual orientation was performed to calculate adjusted odds ratios. All reported comparisons and adjusted odds ratios are statistically significant at least at p<0.05. This means that there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance.

Looking Ahead

This brief demonstrates significant associations between school-related protective factors and LGBTQ middle and high school students’ suicide risk. The findings suggest that attending a school with a GSA or other similar club, learning about LGBTQ people and experiences, having access to a gender-neutral bathroom, and having teachers who respect their pronouns are all associated with lower suicide risk among LGBTQ students in middle and high school. Furthermore, students attending schools with these characteristics reported higher rates of having an LGBTQ-affirming school compared to those without them, which is also associated with lower suicide risk (Trevor, 2022). Alarmingly, just under 1 in 3 (30%) of LGBTQ students in middle school or high school report not having access to any of these protective factors. Furthermore, the disparity between middle and high school student access to them is particularly concerning given the higher rate of suicide attempts among LGBTQ students in middle school (20%) compared to high school (16%). Overall, these findings provide concrete actions for educators and administrators to take in ensuring that all of their students are safe and affirmed in the spaces they are mandated to be in.

Recently passed state laws may prevent many of these important actions to affirm LGBTQ young people such as creating curriculum and offering student clubs that affirm LGBTQ young people, implementing policies around respecting pronouns, and providing gender-neutral bathrooms, despite the protective associations they have for LGBTQ students’ mental health. As of June 2023, over 100 curriculum censorship state-level active bills have been proposed in the United States (The Trevor Project, 2023a). These bills are in direct contradiction to these findings and other scholarship (Russel et al, 2018.; Hatzenbuehler 2011), which have documented the relationships between the affirmation of LGBTQ identities in schools and better mental health among LGBTQ students. Parents/caregivers, teachers, school staff, and other stakeholders should advocate on behalf of LGBTQ young people to ensure they are just as comfortable, safe, and affirmed as their cisgender and straight peers at school.

The Trevor Project remains committed to providing support to LGBTQ young people in schools. Our advocacy team encourages schools to implement the Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention which was developed by The Trevor Project, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), the American School Counselor Association (ASCA), and the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP). Our website offers a number of resources for adults working with LGBTQ young people, including the Guide to Being an Ally to Transgender and Nonbinary Youth, How to Support Bisexual Youth, and Preventing Suicide. Our TrevorSpace social media platform connects young people with supportive peers, and our 24/7 crisis services are available in three different modalities – phone, chat, and text – for LGBTQ young people to connect with affirming counselors when they are in crisis.

References

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2011) The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics, 127(5):896-903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020.

- Johns MM, Lowry R, Haderxhanaj LT, et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly, 69(Suppl-1):19–27. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3external

- Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., & Menard, L. (2022). The 2021 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of LGBTQ+ youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN.

- Russell, S.T., Pollitt, A.M., Li, G., & Grossman, A. H. (2018) Chosen name use Is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(4):503-505. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003.

- The Trevor Project. (2021). The Trevor Project Research Brief: LGBTQ Youth Suicide Prevention in Schools.

- The Trevor Project. (2022). 2022 U.S. national survey on LGBTQ youth mental health. [PDF]

- The Trevor Project. (2023). 2023 U.S. national survey on the mental health of LGBTQ young people. [PDF]

- The Trevor Project. (2023a). LGBTQ Legislation Heatmap.

The authors of this brief acknowledge and extend our deepest thank you to J. Nicholas Hobbs, M.S. for its initial draft.

For more information please contact: [email protected]