EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

LGBTQ young people who are of Latino/a, Latiné, Latinx, or Hispanic origin, henceforth referred to as Latinx, hold multiple marginalized identities. This can increase their susceptibility to negative experiences based on both their race or ethnicity and their sexual orientation or gender identity. This intersection of identities may also act as a protective factor, allowing them to draw strength from multiple identities and sources of pride. However, research has largely failed to quantitatively explore their experiences. This report uses data from a national sample of nearly 6,900 Latinx LGBTQ youth ages 13 to 24 who participated in The Trevor Project’s 2023 National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People. The study contributes to our understanding of the mental health and well-being of LGBTQ young people who are Latinx, including findings specific to Mexican, Cuban, and Puerto Rican LGBTQ young people in the United States.

Key Findings

There is important racial, sexual, and gender diversity within our sample of Latinx LGBTQ young people that must be acknowledged.

- 28% of our sample of Latinx LGBTQ young people were Mexican, 5% were Puerto Rican, 2% were Cuban, with others representing Columbian, Spanish, Venezuelan, Guatemalan, Dominican, and Brazilian origins, to name a few

- 9% of Latinx LGBTQ young people were born outside of the U.S., including 13% of exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people and 5% of multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people

- 23% of Latinx LGBTQ young people primarily spoke Spanish at home

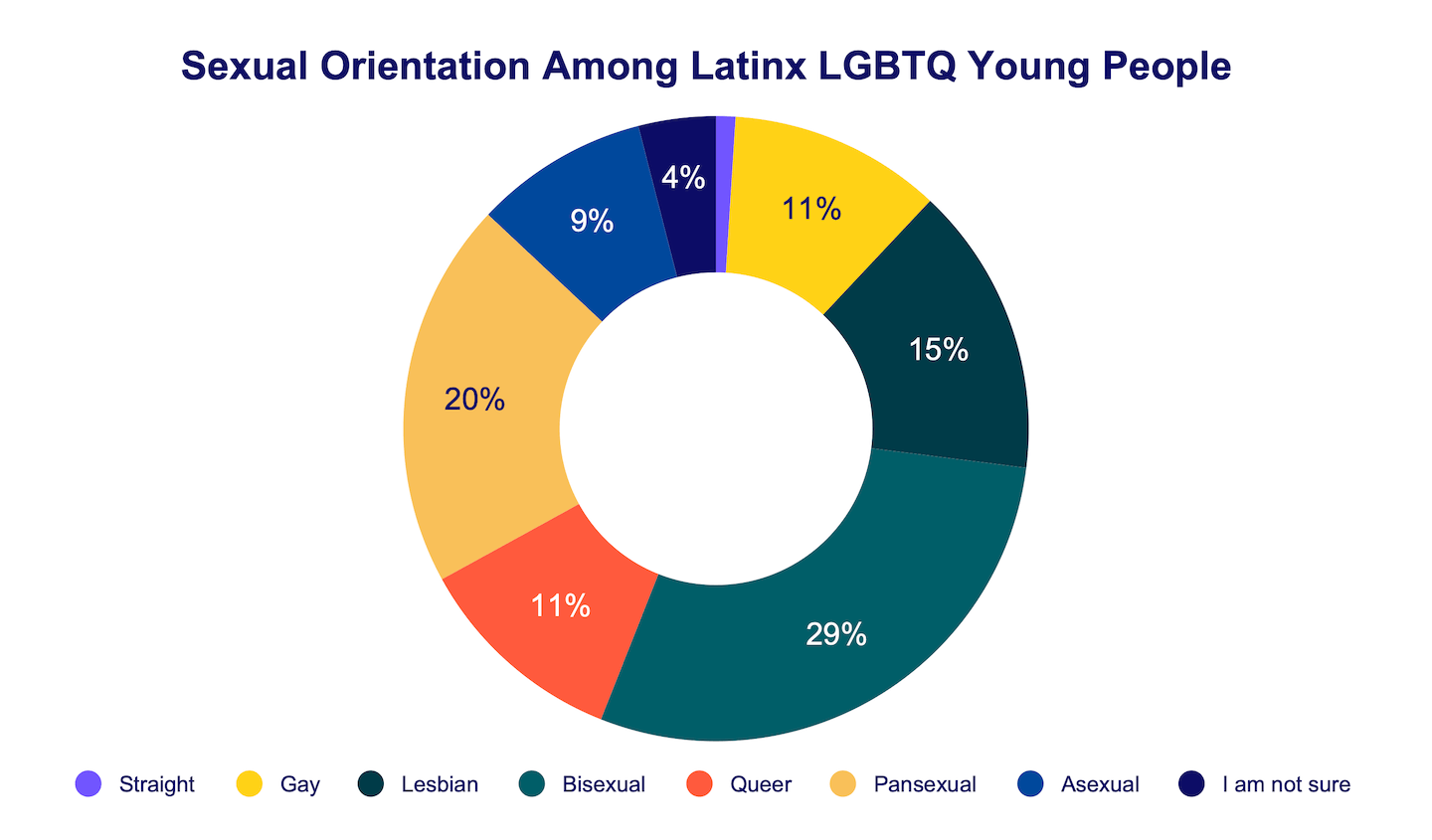

- 29% of Latinx LGBTQ young people identified as bisexual, 20% as pansexual, 15% as lesbian, 11% as gay, 11% as queer, and 9% as asexual

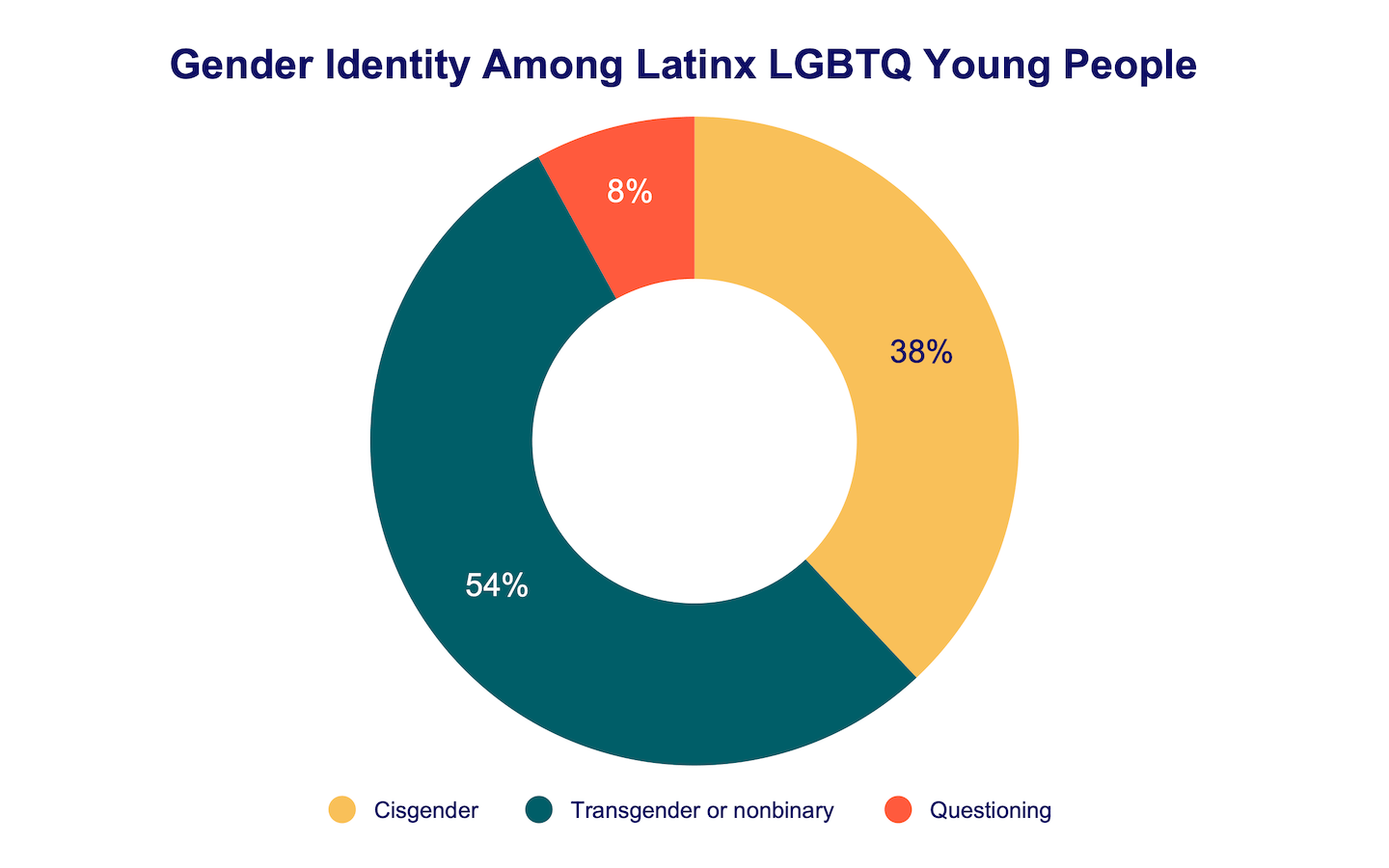

- 54% of Latinx LGBTQ young people were transgender or nonbinary

Latinx LGBTQ young people often report mental health challenges, including suicidal thoughts.

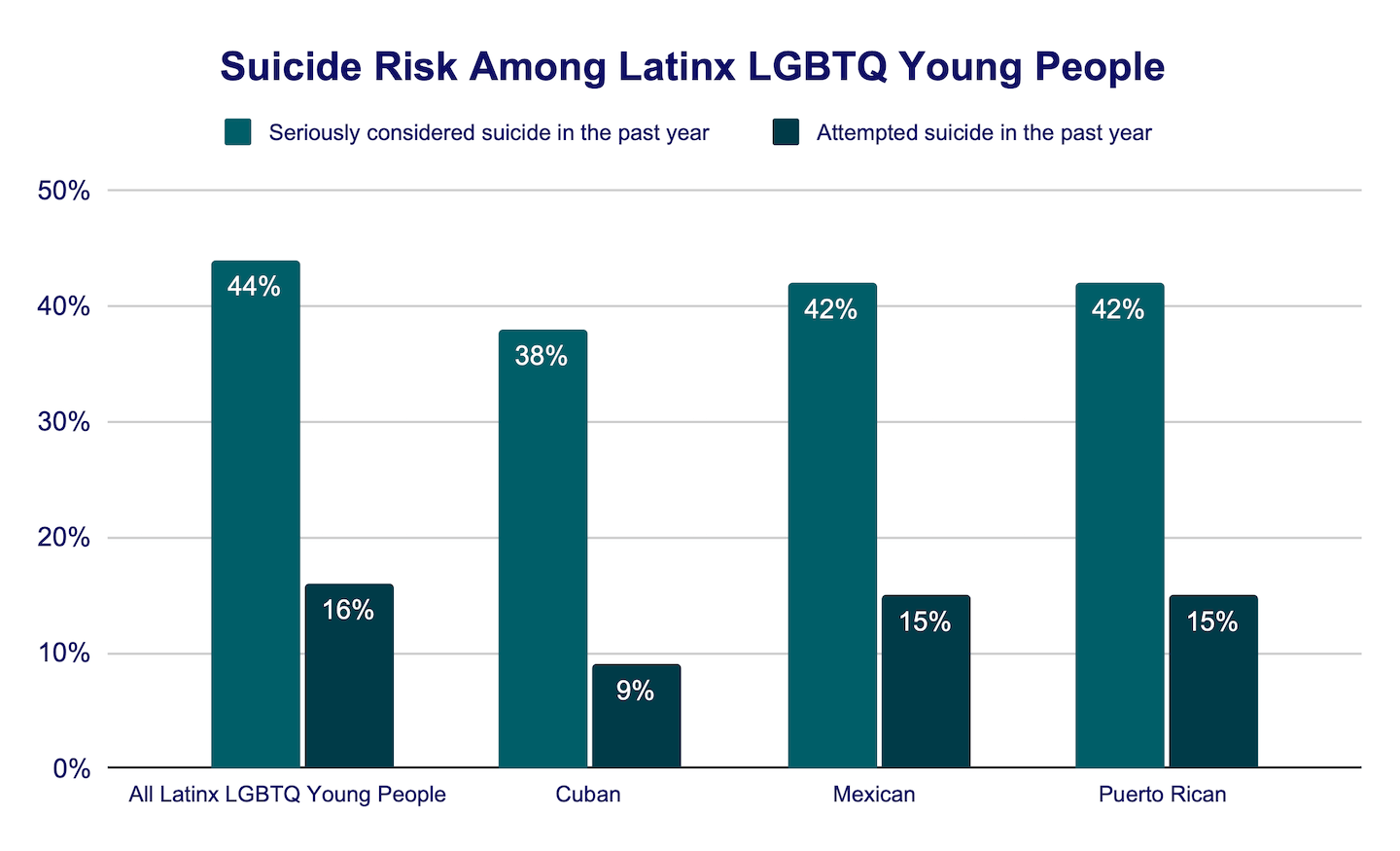

- 44% of Latinx LGBTQ young people seriously considered suicide in the past year, including 53% of Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people compared to 32% of Latinx cisgender LGBQ young people

- 16% of Latinx LGBTQ young people attempted suicide in the past year, including 21% of Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people compared to 9% of Latinx cisgender LGBQ young people

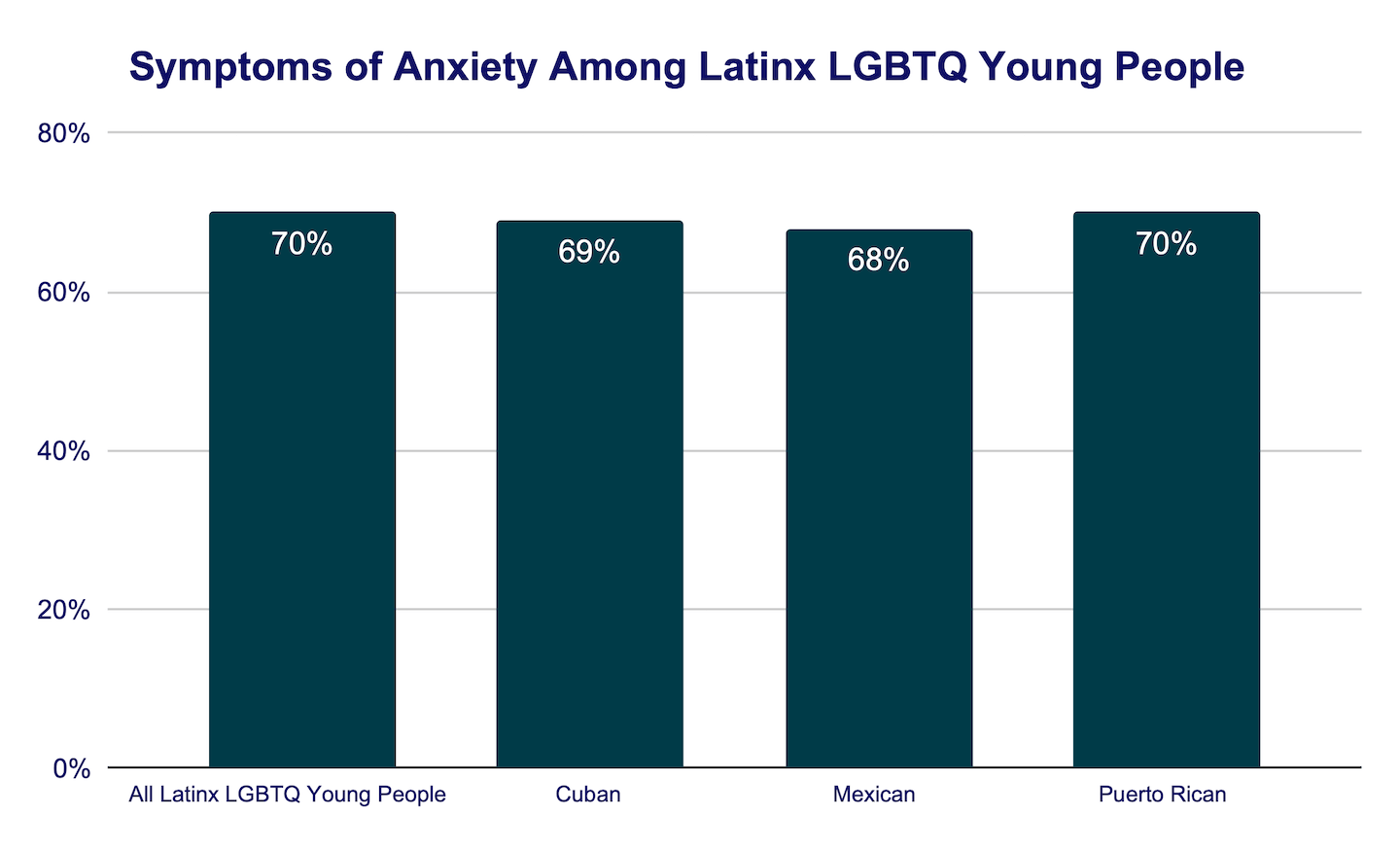

- 70% of Latinx LGBTQ young people reported having symptoms of anxiety in the past two weeks

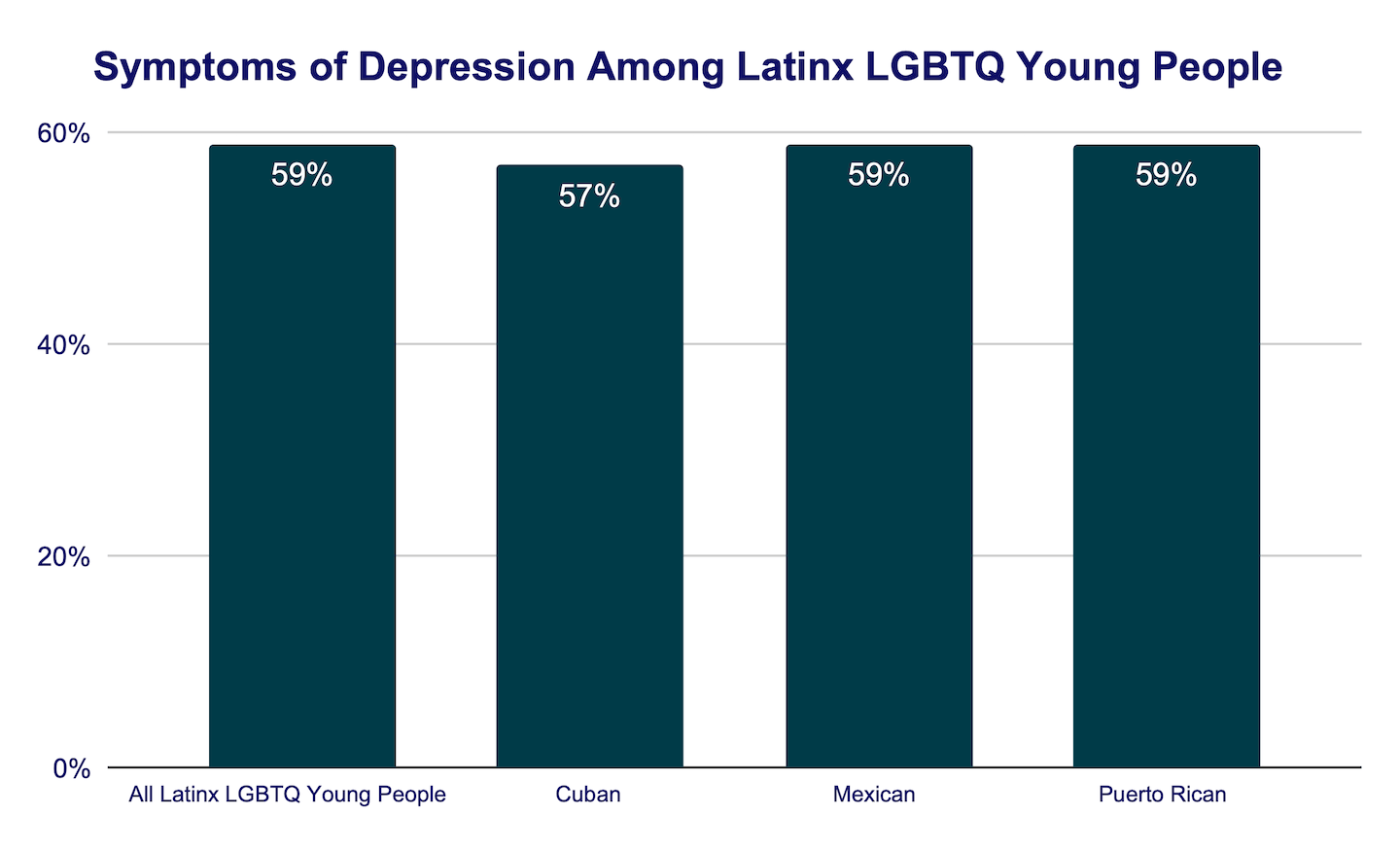

- 59% of Latinx LGBTQ young people reported having symptoms of depression in the past two weeks

Latinx LGBTQ young people experience unique stressors in addition to those common among all LGBTQ young people.

- 60% of Latinx LGBTQ young people reported that someone tried to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity, with 39% indicating that this pressure came from a parent or caregiver

- 39% of Latinx LGBTQ young people reported discrimination based on their race/ethnicity in the past year

- 66% of Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people reported discrimination based on their gender identity in the past year

- 23% of Latinx LGBTQ young people were physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year

- 34% of Latinx LGBTQ young people worried about themselves or someone in their family being detained or deported due to immigration policies, compared to only 5% of non-Latinx LGBTQ young people

While there are challenges faced by Latinx LGBTQ young people, several protective factors can mitigate their suicide risk.

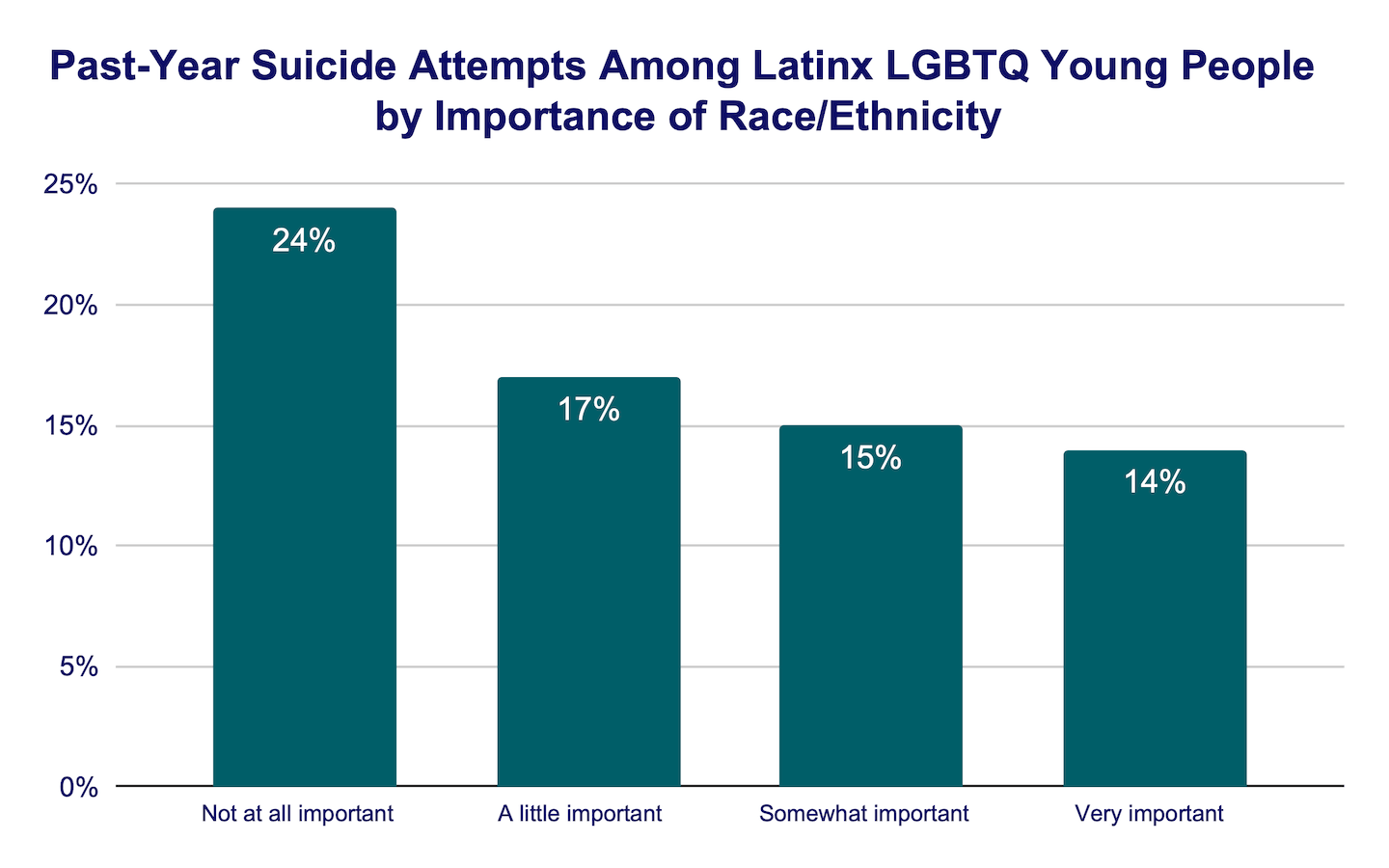

- Latinx LGBTQ young people who feel that their race/ethnicity is an important part of who they are had 24% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year

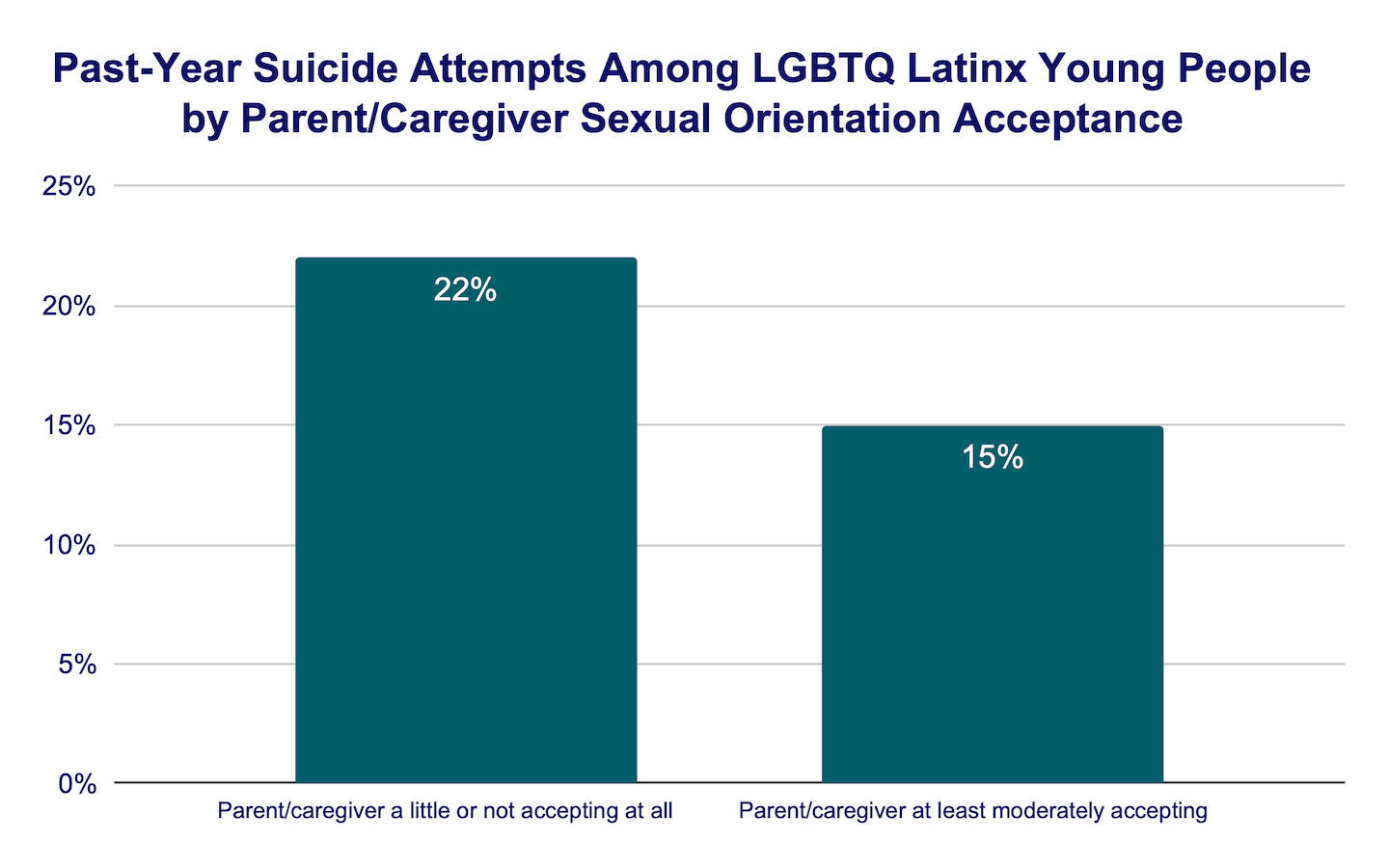

- Parental acceptance of their child’s sexual orientation or gender identity was a protective factor against suicide for Latinx LGBTQ young people

- Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people whose pronouns were respected by the people they lived with reported lower suicide rates than those who lived with people who did not respect their pronouns

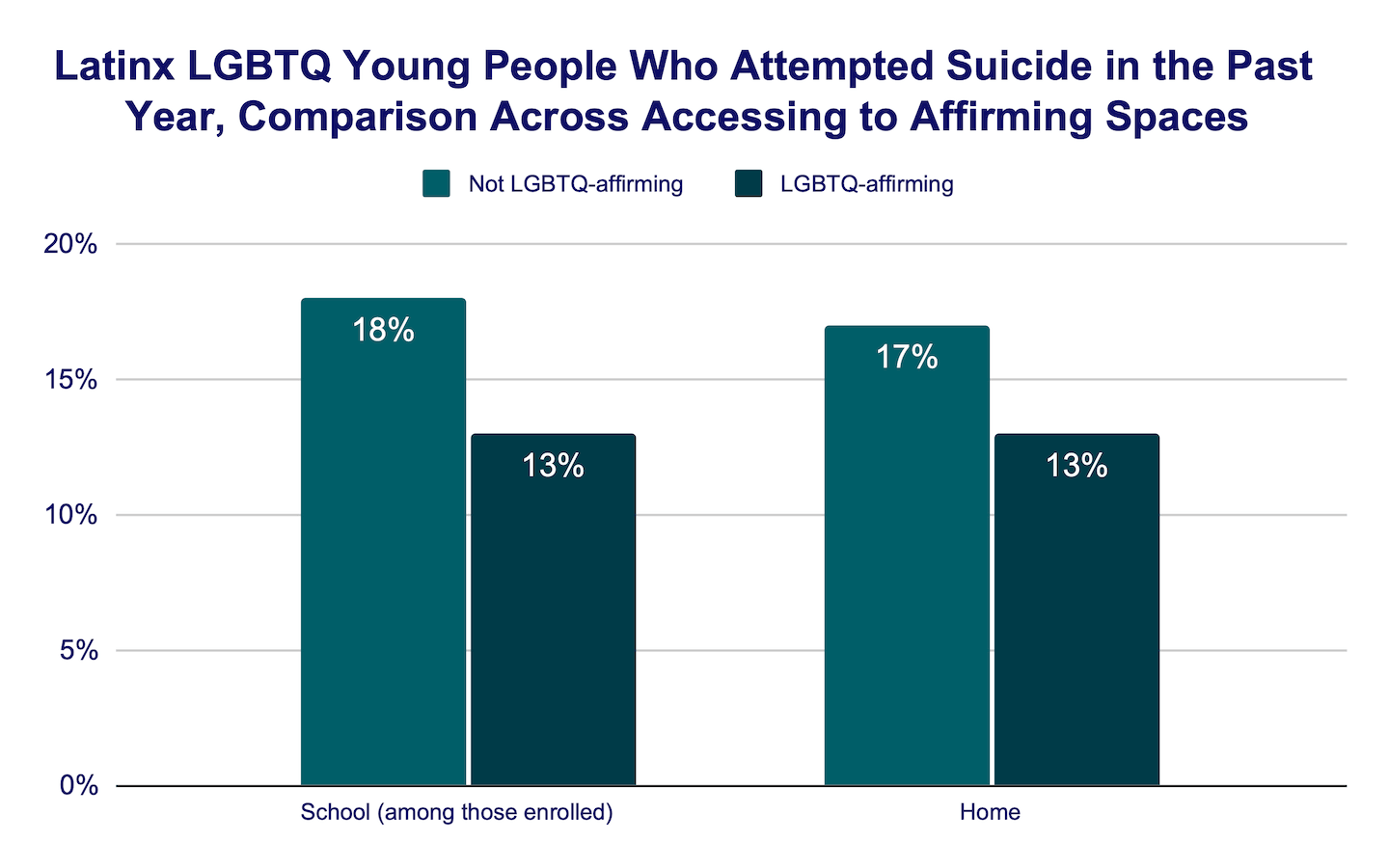

- Latinx LGBTQ young people who had access to LGBTQ-affirming homes and schools had lower rates of suicide attempts compared to Latinx LGBTQ youth without access to such spaces

Methodology Summary

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data through an online survey platform between September and December 2022. The survey was available in both English and Spanish. An analytic sample of over 28,000 young people ages 13 to 24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. All participants were asked, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” They were provided the following options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, White/Caucasian, Middle Eastern or North African, more than one race or ethnicity, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Young people who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question where they were able to select with which races or ethnicities they identified. The current analyses include the 6,867 LGBTQ young people who either identified as exclusively Hispanic or Latino/Latinx or who identified as multiracial Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, henceforth just referred to as Latinx, unless otherwise specified. We understand and respect that people of Hispanic or Latino/Latinx descent use a variety of terms to describe their shared heritage (Arevalo, 2023; McGee, 2023). We have opted to use the term Latinx to be as inclusive as possible of the transgender and nonbinary young people in our sample with the understanding that this term may not be used by everyone. Our upcoming National Survey will specifically ask Latinx LGBTQ young people to share the term which they feel most accurately captures the intersection of their racial and LGBTQ identities in order to be confident that our language is salient to the individuals we aim to support in our work.

Recommendations

Latinx LGBTQ young people report higher rates of mental health challenges, including suicide attempts in the past year, compared to our broader LGBTQ youth sample. In addition to risk factors that all LGBTQ young people are frequently exposed to (e.g., anti-LGBTQ discrimination and victimization), Latinx LGBTQ young people also experience stressors unique to their experience as Latinx individuals in the U.S., such as fears associated with immigration policies and race- and immigration-based discrimination. However, their risk for suicide is ameliorated when they have LGBTQ supportive and affirming people, schools, and homes. Therefore, stakeholders must confront both systemic barriers to Latinx LGBTQ young people’s mental health and well-being as well as work toward LGBTQ inclusion in existing Latinx mental health frameworks. Given the importance and protectiveness of culture and family, intervention efforts must be culturally salient, available in multilingual formats, and mindful of the impact that immigration policies can have on Latinx LGBTQ young people’s mental health.

BACKGROUND

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people often face mental health disparities compared to their straight and cisgender peers. LGBTQ young people report higher rates of anxiety and depression and are more likely to engage in self-harm, seriously consider suicide, and attempt suicide compared to straight, cisgender young people (Gaylor, et al., 2023; Johns et al., 2020). This disparity in mental health outcomes is not inherent to being LGBTQ. Instead, it arises from chronic stress stemming from negative experiences associated with holding a marginalized social status in society (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003). Quite often, in addition to common stressors faced by most young people, LGBTQ young people are challenged with additional stressors such as rejection, victimization, bullying, and discrimination (Kosciw et al., 2020). Such experiences can lead to internalized homophobia, biphobia (Baams et al., 2015), and transphobia (Pellicane & Ciesla, 2021); perceived burdensomeness or beliefs that others would be better off without them (Baams et al., 2015), and overall poor mental health (Green, Price, & Dorison, 2021). However, the LGBTQ community is diverse, with this diversity bringing strength and its own set of unique experiences that may lend to either decreased or increased exposure to these negative experiences and resultant poor mental health outcomes. For example, research finds that transgender and nonbinary young people report rates of poor mental health that are higher than cisgender young people (Johns et al., 2019), even when compared to cisgender LGBQ young people (Price-Feeney et al., 2020). Young people who are bisexual, pansexual, queer, or multisexual often report more mental health challenges compared to young people who are gay or lesbian (Price et al., 2021). Important intersectional differences also exist among LGTBQ young people who hold multiple marginalized identities, such as young people who are both Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) and LGBTQ (Price et al., 2022) or Black and LGBTQ (Price et al., 2020).

Latinx people in the United States face their own distinctive challenges and experiences that may put them at increased risk for poor mental health outcomes. To understand the intersection of being both Latinx and LGBTQ, one must also understand the historical and present context of many Latinx people in the U.S. Spanish-speaking and Spanish-surnamed individuals are often subjected to racist and xenophobic stigma and, as a result, face discrimination and other negative experiences, such as reduced income, poor health care, inadequate nutrition, among others (Perez-Escamilla, 2010). Research finds that Latinx people also have adverse psychological reactions to prejudice and discrimination, including self-hatred (Feagin & Cobas, 2015). While recent immigration policies and rhetoric have heightened anti-immigration sentiments in the U.S., Latinx people have historically been uniquely targeted by such discrimination, and in turn, experienced decreased access to needed services (Massey, 2009). It is important to note that the category of Latinx is inclusive of individuals from many different countries who have a variety of cultural practices and experiences within the U.S.; however, despite intra-group differences, researchers have found some universal cultural values across many Latinx families that may impact mental health. Within the Latinx community, Latinx young people may find that familismo, or close family relations that place the needs of the family above one’s own (Falicov, 2014), is frequently associated with well-being (Stein et al., 2015); however, it may also place Latinx young people at risk for not taking care of their own mental health needs (Barrera & Longoria, 2018). Relatedly, machismo and marianismo, or strict adherence to traditional gender roles within the Latinx community, may prevent Latinx young people from acknowledging and discussing the mental health challenges they may be experiencing (Barrera & Longoria, 2018).

Latinx LGBTQ young people may be at higher risk for poor mental health due to the unique stressors arising from the intersection of their LGBTQ and Latinx identities. The intersectional perspective suggests that a person’s social position in society, influenced by factors such as race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and physical abilities, as well as how these factors interact, creates unique experiences (Crenshaw, 2017). This is particularly true for those who have multiple marginalized identities (Collins & Bilge, 2020). Despite its potential implication, the mental health experiences at the intersection of being Latinx and LGBTQ are not frequently explored among young people. That said, existing qualitative research finds that experiences related to racial-ethnic discrimination, immigration, religious messaging, and acculturation may all contribute to stress for Latinx LGBTQ young people (Schmitz et al., 2019; Silvia et al., 2018; Valentín-Cortés et al., 2020). Additionally, GLSEN’s report on Latinx LGBTQ youth in schools concluded that they have distinctive school experiences due to their identities, such as feeling unsafe due to their race/ethnicity or being harassed or assaulted due to their sexual orientation (Zongrone, Truong, & Kosciw, 2020). Furthermore, while familismo can be linked to positive outcomes, research finds that Latinx parents and caregivers are less likely to embrace their LGBTQ children (Ryan et al., 2010). In some cases, the bonds of familismo may weaken when a child comes out as LGBTQ, causing feelings of rejection (Gonzalez, Connaughton-Espino, & Reese, 2023). Finally, family and community adherence to machismo and marianismo might exacerbate challenges for Latinx LGBTQ young people, particularly Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people (Ascencio, 2021; Gattamorta, Salerno, & Quidley-Rodriquez, 2019).

It is important to consider that having multiple identities may also serve as a protective factor for Latinx LGBTQ young people. Using a resiliency framework (Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005), embracing multiple identities may in fact be a source of strength for Latinx LGBTQ young people. While one identity may be marginalized in a given context, another identity, or the support one receives from that identity, may be adaptive in that same context. For example, Latinx LGBTQ young people often show higher levels of self-esteem compared to their White counterparts (Ryan et al., 2010), suggesting potential sources of well-being may exist specific to Latinx LGBTQ young people. Furthermore, in response to structural stigma, qualitative research finds that Latinx LGBTQ young people adapt by establishing a sense of control over their own mental and physical health autonomy, which can help counter potential harms (Shmitz, Sanchez, & Lopez, 2019). Latinx young people may also find strength in family support and connection to culture (Przeworski & Piedra, 2020).

To date, research has not adequately examined how Latinx LGBTQ young people’s intersecting identities might affect their mental health risks and well-being. Often citing the lack of Latinx representation in sample sizes for subgroup analyses, quantitative research on the experiences of LGBTQ young people frequently fails to explore the specific within-group experiences of Latinx young people. Additionally, much of the research exploring mental health among Latinx young people does not consider how young people’s sexual orientation and gender identity may influence their experiences and therefore, well-being (Perreira et al., 2019), leaving Latinx LGBTQ young people strikingly understudied. A notable exception is GLSEN’s 2020 report in partnership with the Hispanic Federation and UnidosUS that explored the experiences of Latinx students in schools (Zongrone, Truong, & Kosciw, 2020). Still, the mental health and well-being of Latinx LGBTQ young people remains largely understudied, and their unique needs are under-addressed.

Using a national U.S. sample of nearly 6,900 Latinx LGBTQ young people ages 13 to 24 who participated in our 2023 National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People, this report is the first to exclusively study the mental health and well-being of Latinx LBGTQ young people.

METHODOLOGY

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data using an online survey platform between September and December 2022. An analytic sample of over 28,000 young people ages 13 to 24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. The survey was offered in both English and Spanish. All participants were asked, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, White/Caucasian, Middle Eastern or North African, more than one race or ethnicity, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Young people who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question where they were able to select with which races or ethnicities they identified. While young people who exclusively selected Hispanic or Latino/Latinx reported better mental health outcomes compared to young people who identified as multiracial Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, this difference was accounted for by the fact that multiracial Hispanic or Latino/Latinx young people had higher odds of being transgender or nonbinary and multisexual, both of which are associated with higher odds of mental health risk. Therefore, the current analyses include the 6,867 LGBTQ young people who either identified as exclusively Hispanic or Latino/Latinx or who identified as multiracial Hispanic or Latino/Latinx.

The overall survey included a maximum of 150 questions, including questions on considering and attempting suicide in the past 12 months taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020) and measures of anxiety and depression based on the GAD-2 and PHQ-2, respectively (Plummer et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2010). We conducted separate analyses for Latinx LGBTQ young people: one for those who identified exclusively as Latinx and another for those who identified as multiracial, being Latinx and another race/ethnicity. Where sample sizes were adequate, we also shared findings specific to Mexican, Cuban, and Puerto Rican LGBTQ young people residing in the U.S. These specific analyses did not include multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people. Logistic regression models were used to predict attempting suicide in the past year, adjusting for sex assigned at birth, age, gender identity, and sexual orientation. All reported comparisons and adjusted odds ratios are statistically significant at least at p<0.05. This means that there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance. However, we did not conduct tests for significance in the comparisons between Latinx LGBTQ young people and all LGBTQ young people. This is because the latter group includes Latinx LGBTQ young people, making direct statistical tests inappropriate. The comparison is therefore provided solely for informational purposes.

RESULTS

Diversity of Latinx LGBTQ Young People

Race, Ethnicity, Culture

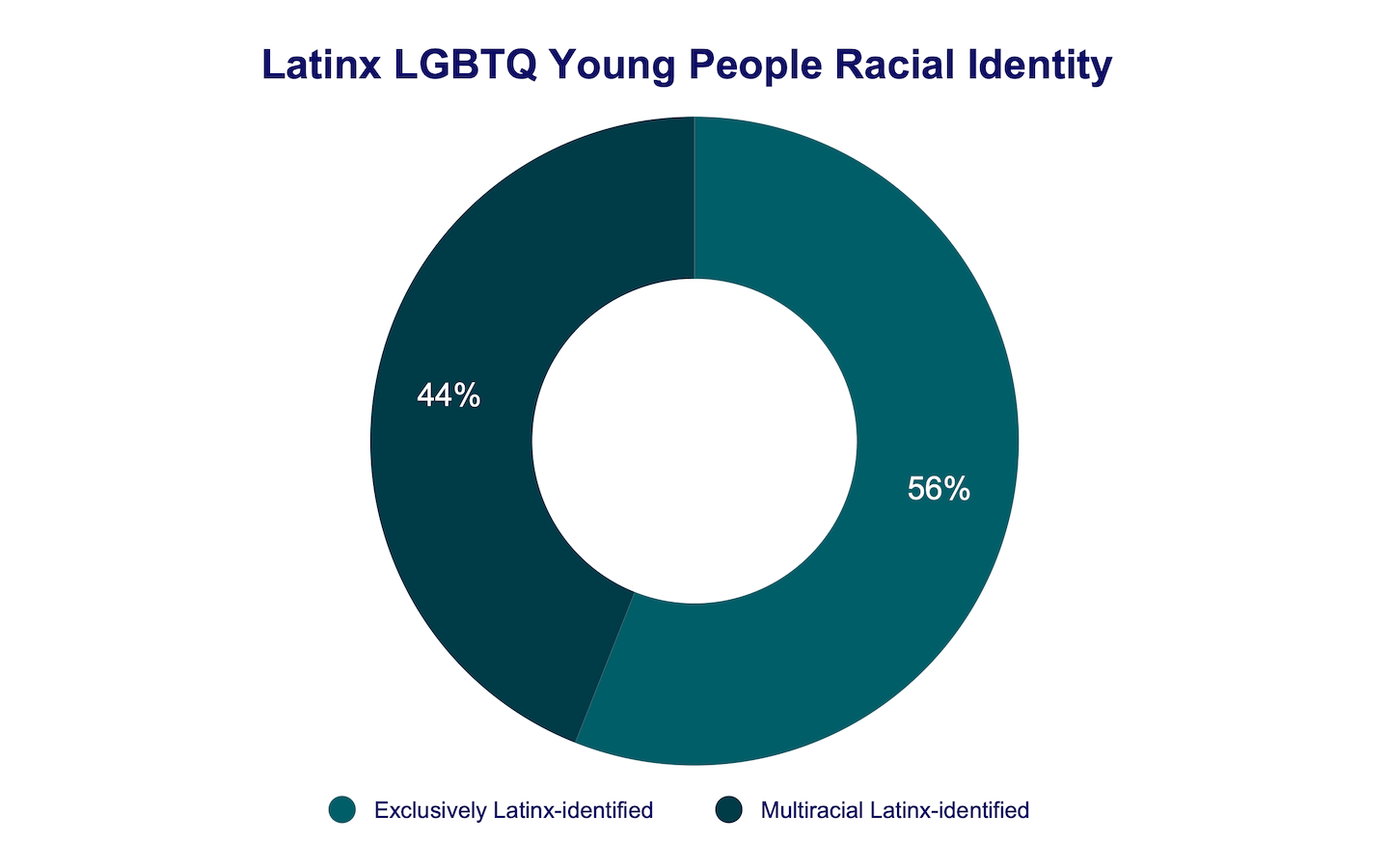

The Latinx LGBTQ people young people in our sample span a diverse range of cultures and experiences. Overall, 56% of them exclusively identified as Latinx and 44% as multiracial Latinx (see sample demographics on Page 36). Within the sample, 28% were exclusively Mexican, 5% Puerto Rican, 2% Cuban, and 1% each identified as Brazilian, Colombian, Dominican, Guatemalan, Peruvian, Salvadorian, Spanish, and Venezuelan. Additionally, 2% belonged to other Latinx identities not listed (e.g., Argentinean, Costa Rican, Nicaraguan, and Portuguese, among others) and 12% were multiracial within Latinx identities (e.g., Mexican and Peruvian). Less than 1% identified as Afro-Latinx, Bolivian, or Ecuadorian. Among those who were multiracial Latinx, 77% also identified as White, 18% as Native/Indigenous, 15% as Black, 13% as Asian American/Pacific Islander, and 3% as North African/Middle Eastern.

Overall, 9% of Latinx LGBTQ young people in our sample were born outside of the U.S. This includes 13% of those who identified as exclusively Latinx, 5% of multiracial Latinx, 20% of Cuban young people, 15% of Puerto Rican young people, and 7% of Mexican young people. For comparison, 7% of the overall LGBTQ sample were born outside the U.S. Additionally, 52% of Latinx LGBTQ young people had at least one parent who was born outside of the U.S. (64% of exclusively identified Latinx young people’s parents and 37% of multiracial Latinx young people), compared to 27% of the entire LGBTQ sample.

While the majority (74%) of the Latinx LGBTQ young people in our sample primarily spoke English at home, 23% spoke Spanish, 1% spoke Portuguese, and another 2% used other languages including a mixture of English and Spanish (often referred to as Spanglish) and American Sign Language.

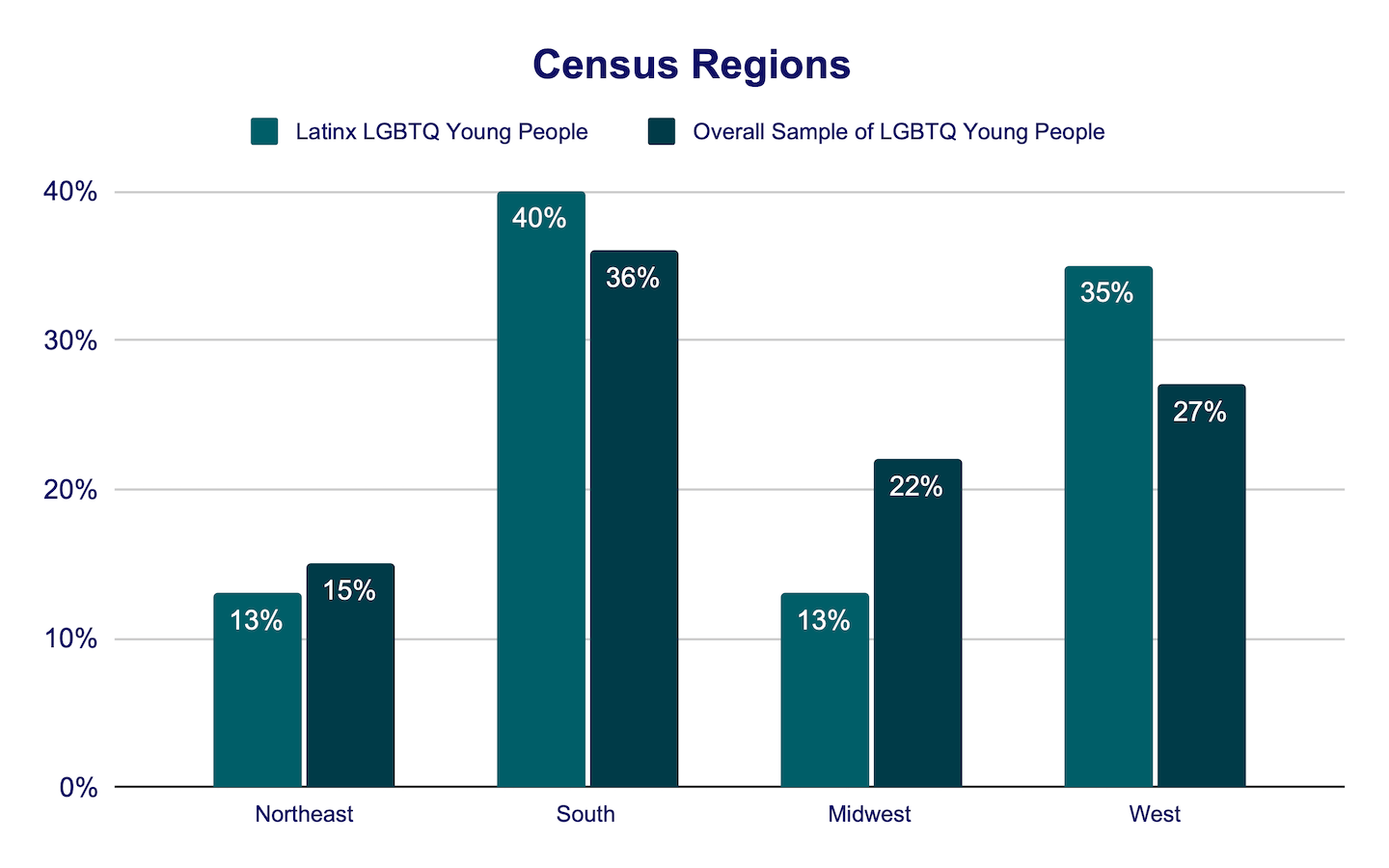

Geographically, Latinx LGBTQ young people were more concentrated in the Southern (40%) and Western (34%) regions of the U.S. compared to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people (36% and 27%, respectively). Latinx LGBTQ young people were also less represented in the Midwest (13%) compared to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people (22%).

Sexual Orientation

Latinx LGBTQ young people most commonly identified as bisexual (29%). This was followed by 20% who identified as pansexual, 15% as lesbian, 11% as gay, 11% as queer, 9% as asexual, 1% as straight, and 4% who were unsure or questioning of their sexual orientation. These percentages are nearly identical to those of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people.

Gender Identity and Expression

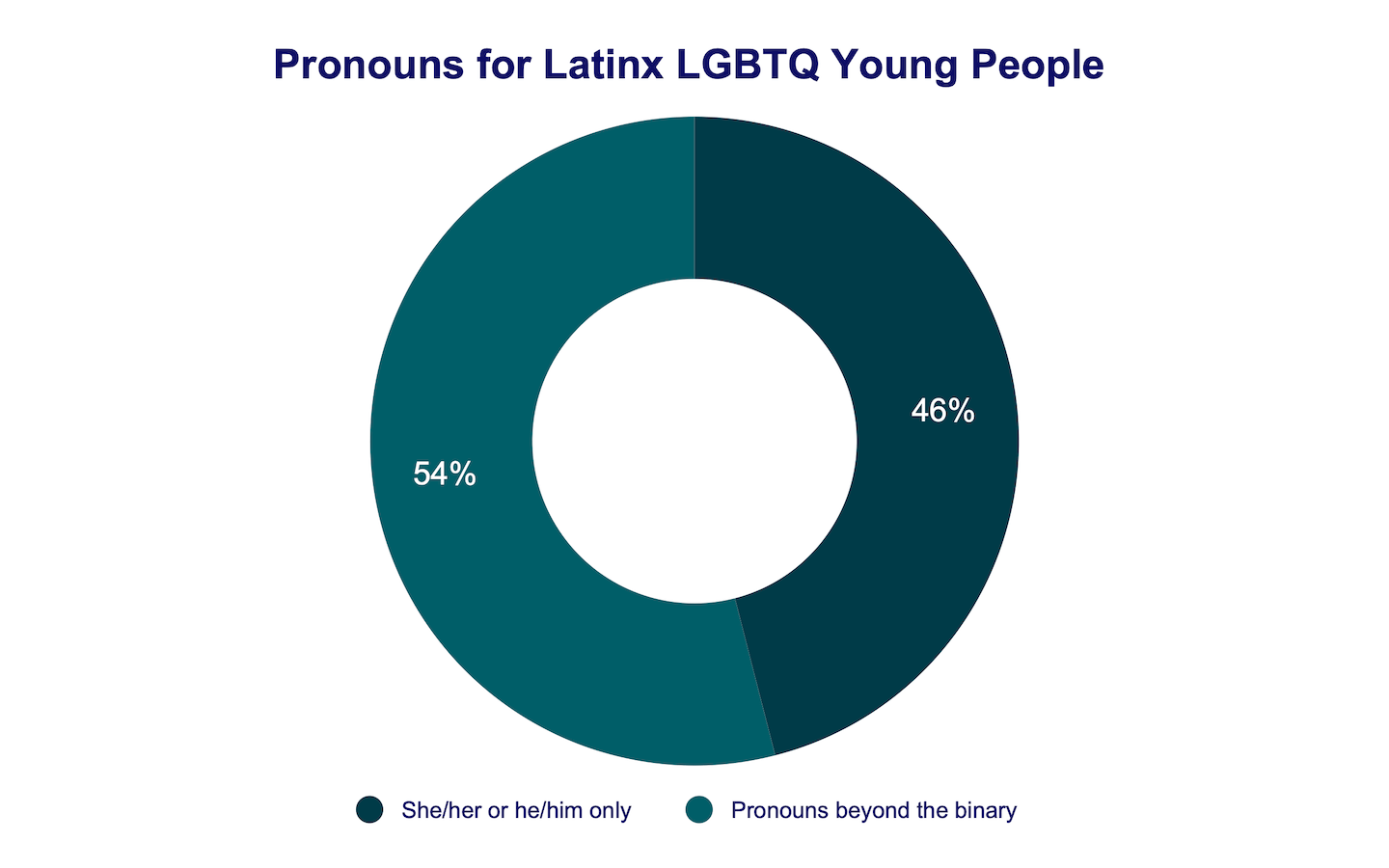

In our sample, 54% of the Latinx LGBTQ young people identified as transgender or nonbinary. This is slightly higher than the 51% in the overall LGBTQ sample. Within specific subgroups of Latinx LGBTQ young people that we could analyze based on sample size, the percentages were similar: 51% identified as transgender or nonbinary among Mexican LGBTQ young people, 48% among Puerto Rican LGBTQ young people, and 50% among Cuban LGBTQ young people. Additionally, 54% of the Latinx LGBTQ young people in our sample used pronouns or pronoun combinations outside the traditional binary construction of gender. This included 12% who used ‘they/them’ exclusively and 21% who combined ‘they/them’ with ‘she/her’ or ‘he/him’. For comparison, 51% of the broader LGBTQ young people sample used such pronouns.

Mental Health and Well-Being Among Latinx LGBTQ Young People

Anxiety and Depression

Latinx LGBTQ young people reported rates of anxiety and depression that were slightly higher when compared to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Seven out of 10 Latinx LGBTQ young people reported symptoms of anxiety in the past two weeks (70%). This compares to 67% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Cuban (69%), Mexzican (68%), and Puerto Rican (70%) LGBTQ young people reported comparable rates of symptoms of anxiety in the past two weeks, however, rates were higher for Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people (76%) compared to cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (62%).

Overall, nearly three in five Latinx LGBTQ young people (59%) reported symptoms of depression in the past two weeks. Similar to symptoms of anxiety, depression symptoms were higher among Latinx LGBTQ young people compared to the overall LGBTQ youth sample (54%). Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people (76%) reported higher rates of depression compared to cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (62%). Rates of recent depression symptoms were similar for Cuban (57%), Mexican (59%), and Puerto Rican (59%) LGBTQ young people.

Self-Harm and Suicide Risk

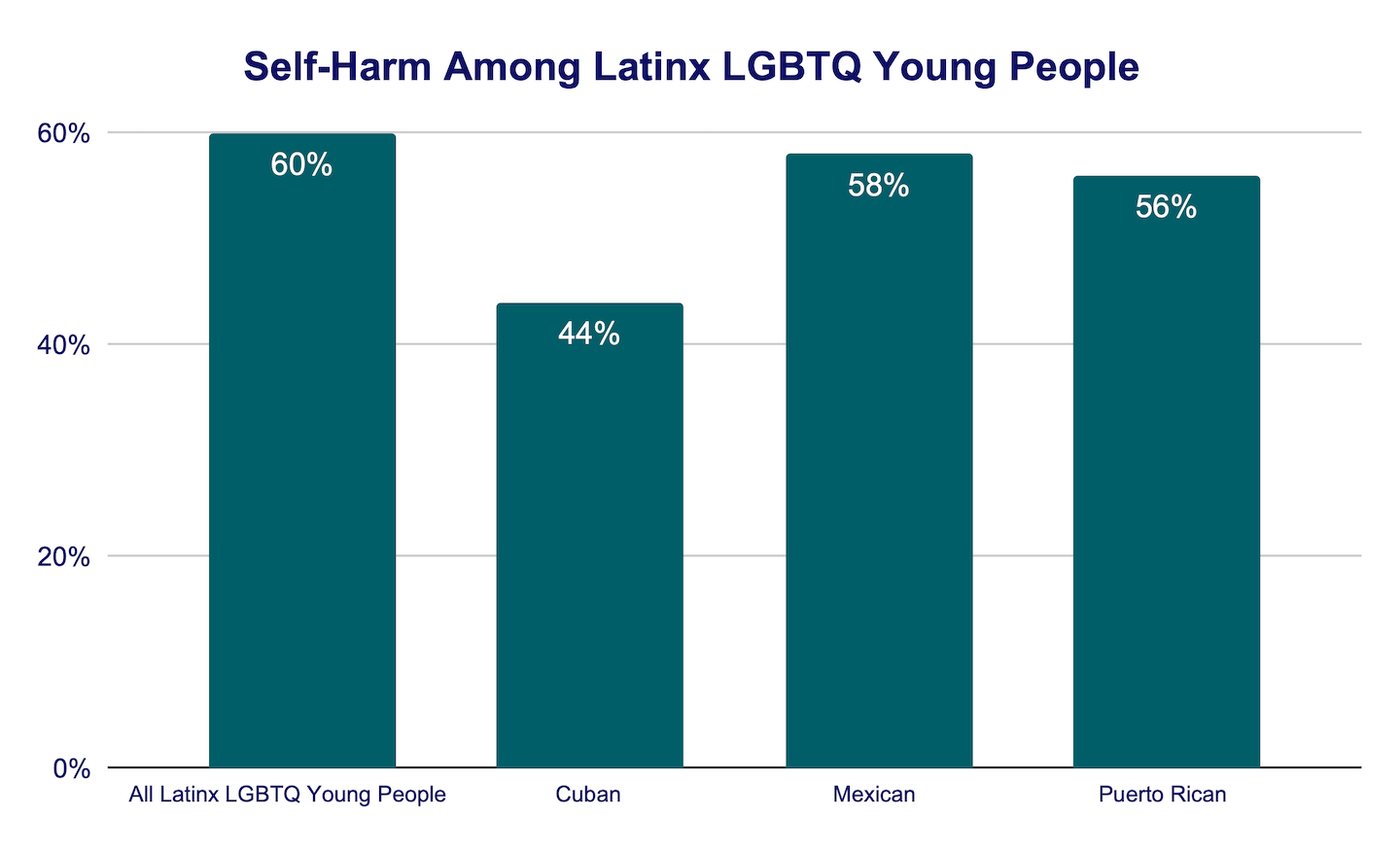

Self-harm, also termed nonsuicidal self-injury or hurting one’s self on purpose, in the past year was reported by 60% of Latinx LGBTQ young people. This compares to 54% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Furthermore, there were significant within-in group disparities by age and gender identity, with Latinx LGBTQ young people ages 13 to 17 reporting higher rates of self-harm (66%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ young people ages 18 to 24 (49%) and transgender and nonbinary Latinx young people reporting higher rates of self-harm (60%) compared to cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (44%). Additionally, Cuban LGBTQ young people reported significantly lower rates of self-harm (44%) compared to both Mexican (58%) and Puerto Rican (56%) LGBTQ young people.

Latinx LGBTQ young people also reported higher rates of suicide risk when compared to the entire sample of LGBTQ young people. Specifically, 44% of Latinx LGBTQ young people seriously considered suicide in the past year, in contrast to 41% in the overall sample of LGBTQ youth. The rates diverge significantly between specific identity groups: over half of transgender and nonbinary Latinx young people (53%) reported seriously considering suicide in the past year compared to just under one in three cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (32%). Furthermore, Latinx LGBTQ young people ages 13 to 17 reported higher rates of seriously considering suicide in the past year (48%) compared to 18 to 24-year-old Latinx LGBTQ young people (38%). Rates were comparable across specific backgrounds with Cuban (38%), Mexican (42%), and Puerto Rican (42%) LGBTQ young people reporting similar percentages.

Across our sample, 16% of Latinx LGBTQ young people attempted suicide in the past year, compared to 14% of all LGBTQ young people in the sample. Latinx LGBTQ young people have 22% higher odds of suicide attempts in the past year compared to non-Latinx LGBTQ young people (aOR=1.22, 95% CI [1.12, 1.34], p<.001). Similar to other mental health indicators, there were disparities across gender identity and age. Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people reported more than two times the rate of attempting suicide in the past year (21%) compared to cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (9%). Similar to seriously considering suicide in the past year, Latinx LGBTQ young people ages 13 to 17 reported higher rates of attempting suicide in the past year (19%) compared to Latinx young people ages 18 to 24 (11%). Finally, while LGBTQ young people who were Cuban reported lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year (9%) compared to those who were Mexican (15%) and Puerto Rican (15%), this difference was not statistically significant.

Risk Factors for Suicide Among Latinx LGBTQ Young People

Access to Mental Health Care

Access to Care

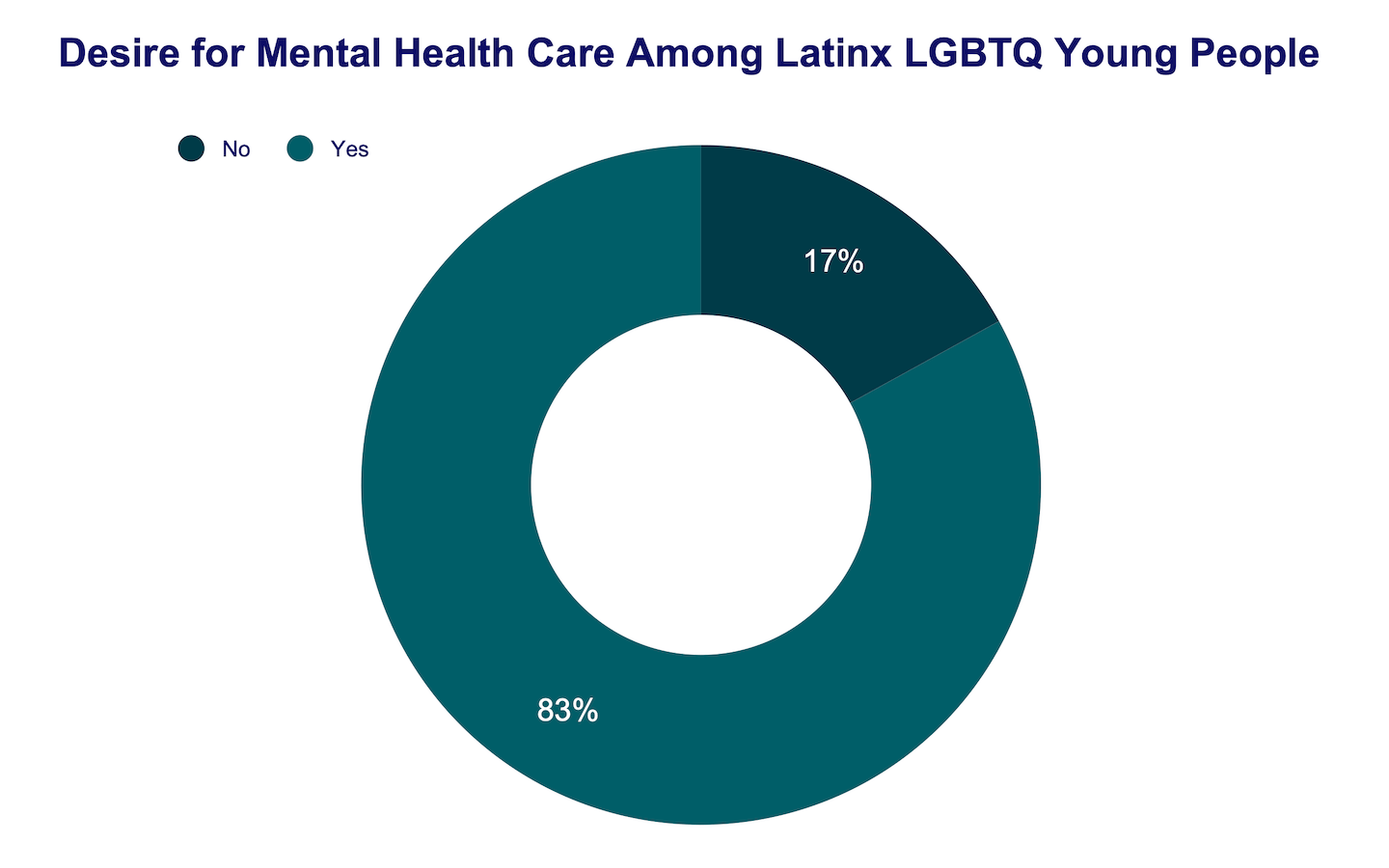

Despite having higher rates of mental health concerns compared to the overall LGBTQ youth sample, Latinx LGBTQ young people often could not access the mental health care they wanted. Of Latinx LGBTQ young people, 83% reported wanting mental health care.

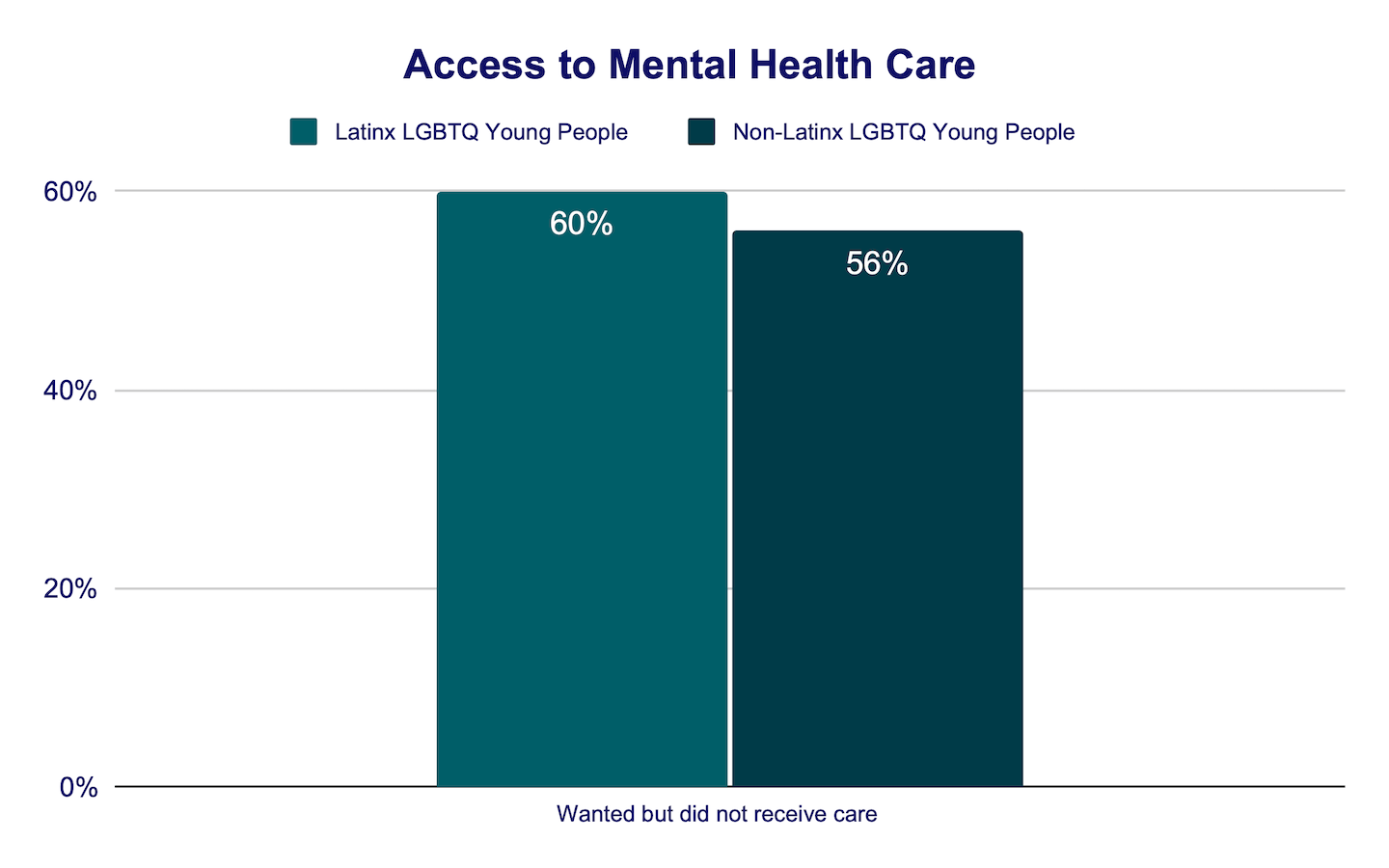

However, 60% of Latinx LGBTQ young people did not receive the care they wanted, which is higher than for the full sample of LGBTQ young people (56%). Furthermore, Latinx LGBTQ young people who were 13 to 17 years old reported higher rates of not accessing wanted mental health care (63%) compared to older Latinx LGBTQ young people (57%), as did LGBTQ young people who were exclusively Latinx (63%) compared to multiracial Latinx (56%). Transgender and nonbinary Latinx young people reported lower rates of not accessing wanted mental health care (57%) compared to cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (63%).

Barriers to Care

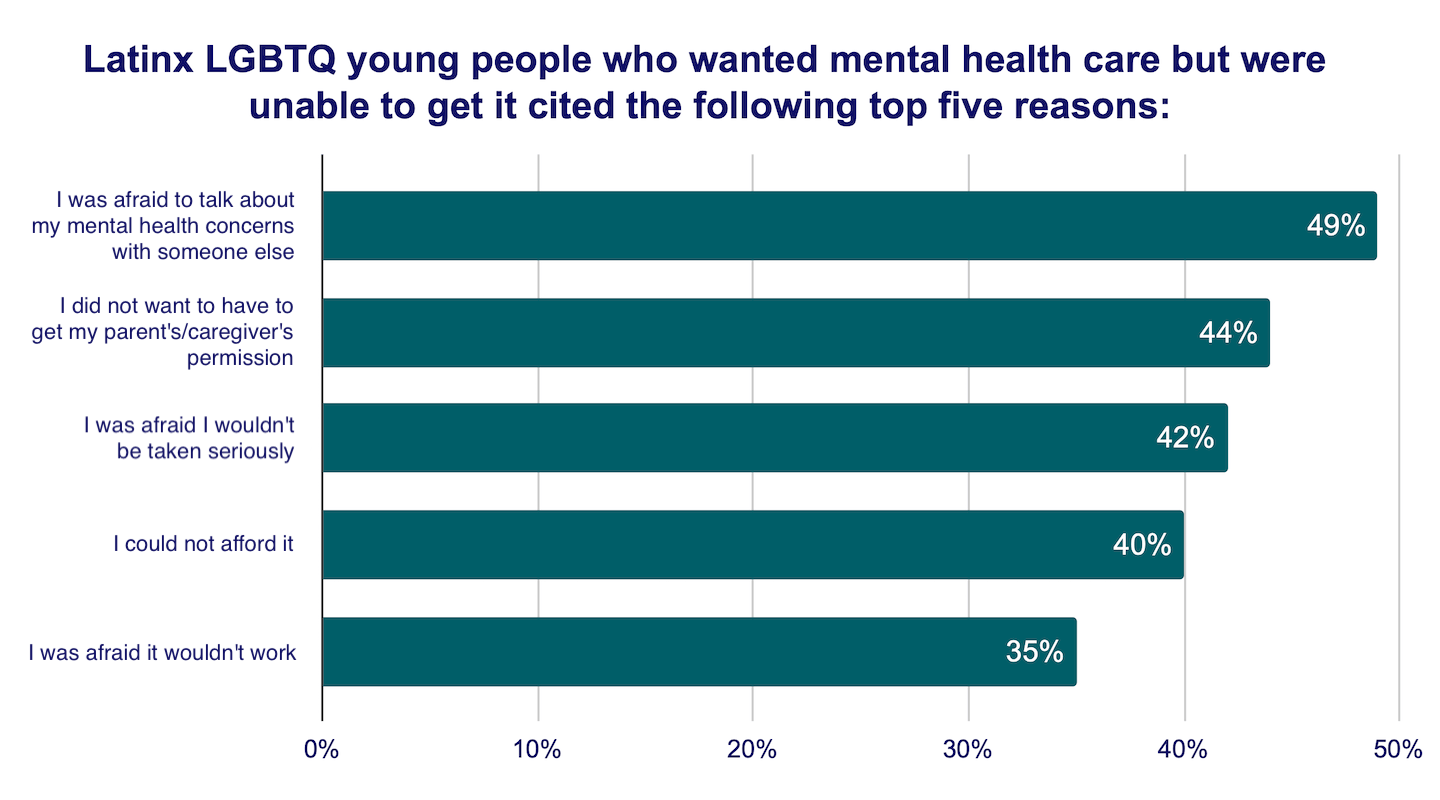

When asked about the barriers preventing them from receiving desired mental health care, nearly half of Latinx LGBTQ young people (49%) said they were afraid to discuss their mental health issues with someone else. Other commonly reported barriers included not wanting to get parental permission (44%), fears of not being taken seriously (42%), concerns about affordability (40%), and doubts about the effectiveness of the treatment (35%).

Conversion Therapy and Change Attempts

Conversion Therapy

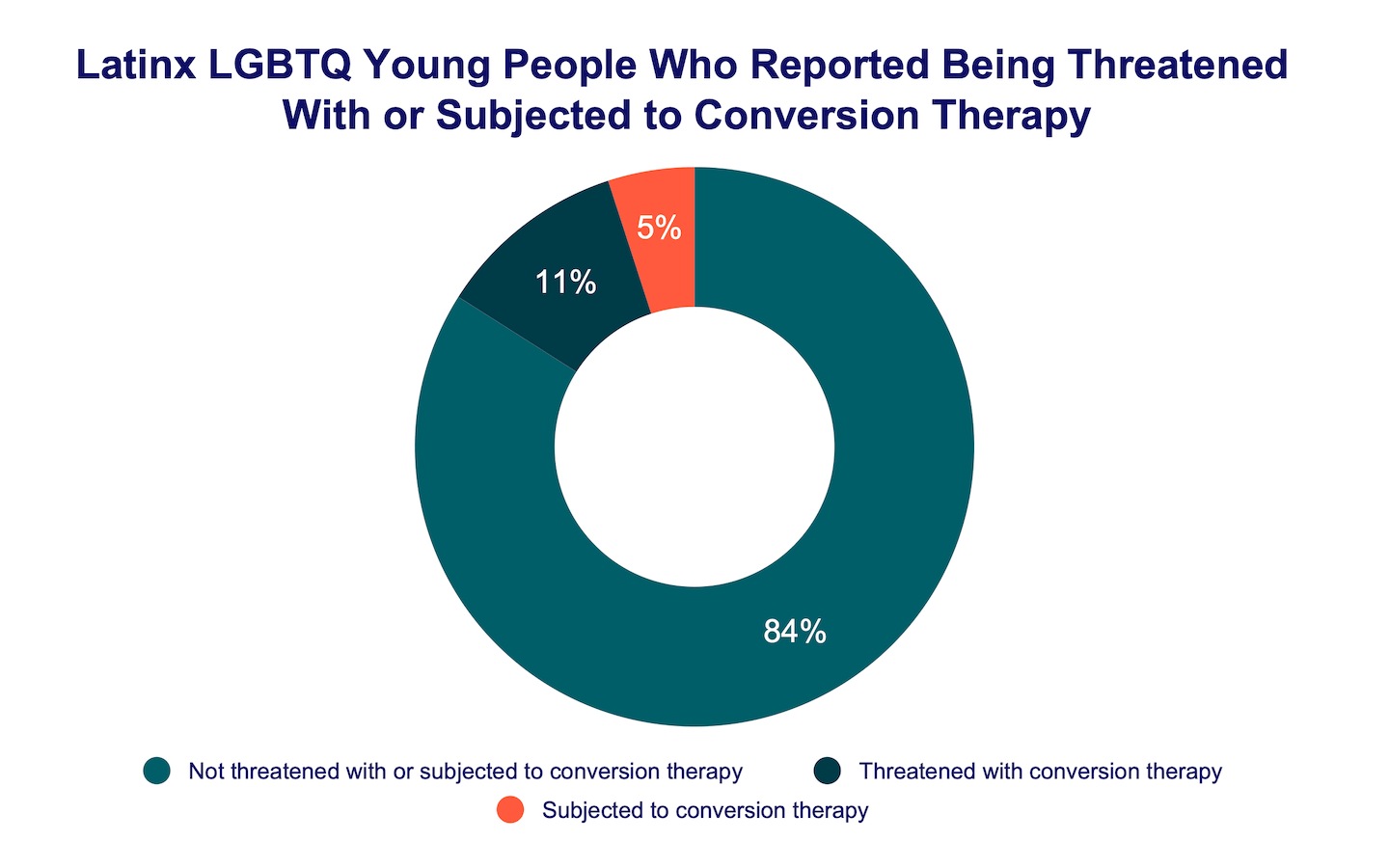

Conversion therapy — attempts by licensed professionals (e.g., psychologists or counselors) or practices by religious leaders to alter sexual attractions and behaviors, gender expression, or gender identity — is still happening in the U.S. despite documented evidence of its harm on the health of LGBTQ young people (Green et al., 2020; Forsythe et al., 2022). Of Latinx LGBTQ young people surveyed, 5% reported ever having been exposed to conversion therapy, while 11% had been threatened with it. Nearly all Latinx LGBTQ young people who were exposed to conversion therapy reported that it happened when they were under the age of 18 (96%), compared to 92% of the entire sample of LGBTQ young people.

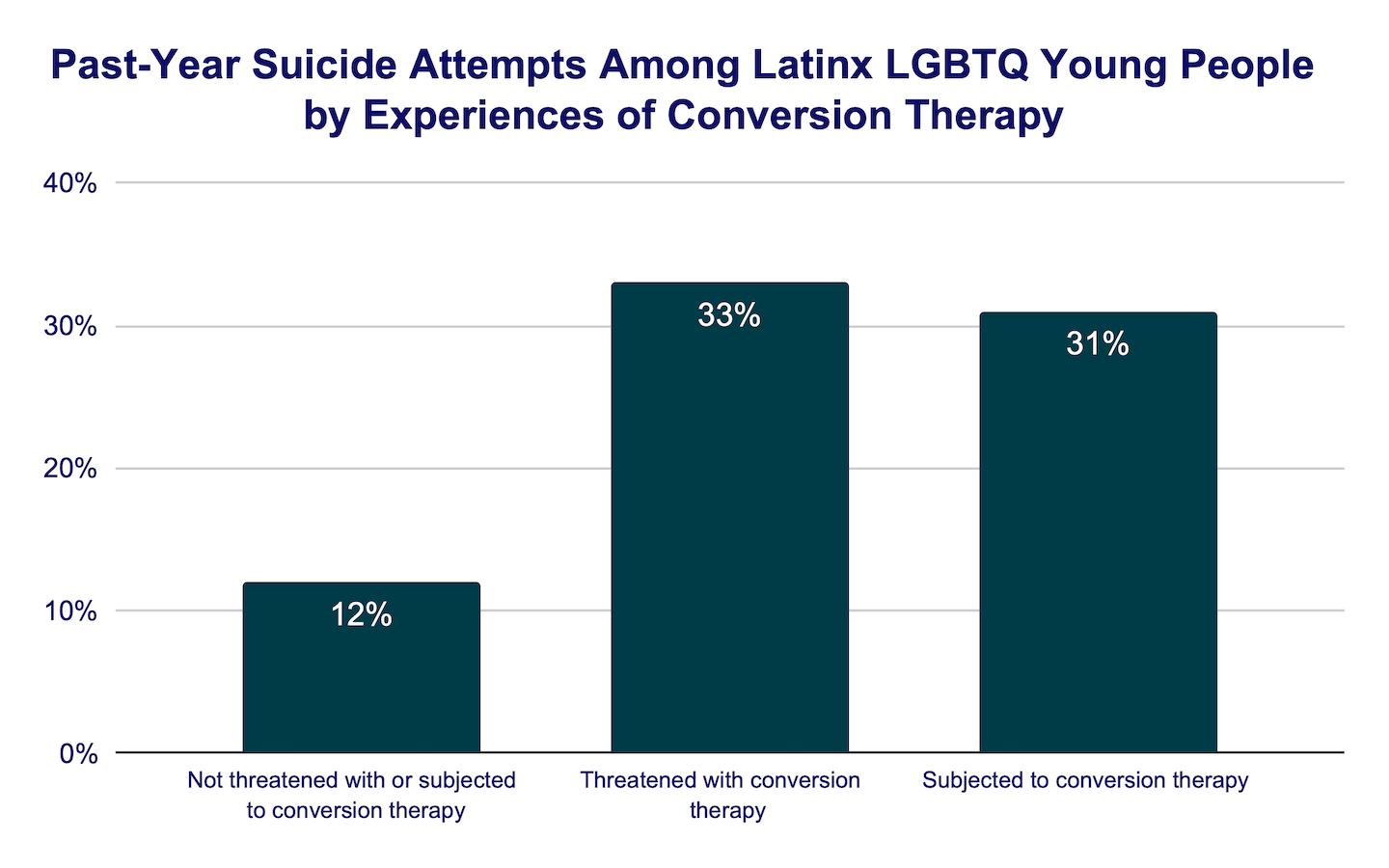

Additionally, 66% of the Latinx LGBTQ young people exposed to conversion therapy reported that it was administered by a personal pastor or priest. This is higher than 59% of the full sample of LGBTQ young people. Just over 1 in 3 (36%) Latinx LGBTQ young people said that a pastor or priest outside of their personal church delivered the therapy, and 27% reported it was from a healthcare provider. Given conversion therapy is a form of identity-related rejection, Latinx LGBTQ young people who were subjected to conversion therapy had almost two and a half times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR = 2.48, 95% CI [1.86, 3.32], p<.001). Importantly, Latinx LGBTQ young people who were ever threatened with conversion therapy, but never subjected to it, reported higher rates of suicide attempts in the past year (33%) compared to those who were neither subjected nor threatened with conversion therapy (12%).

Change Attempts

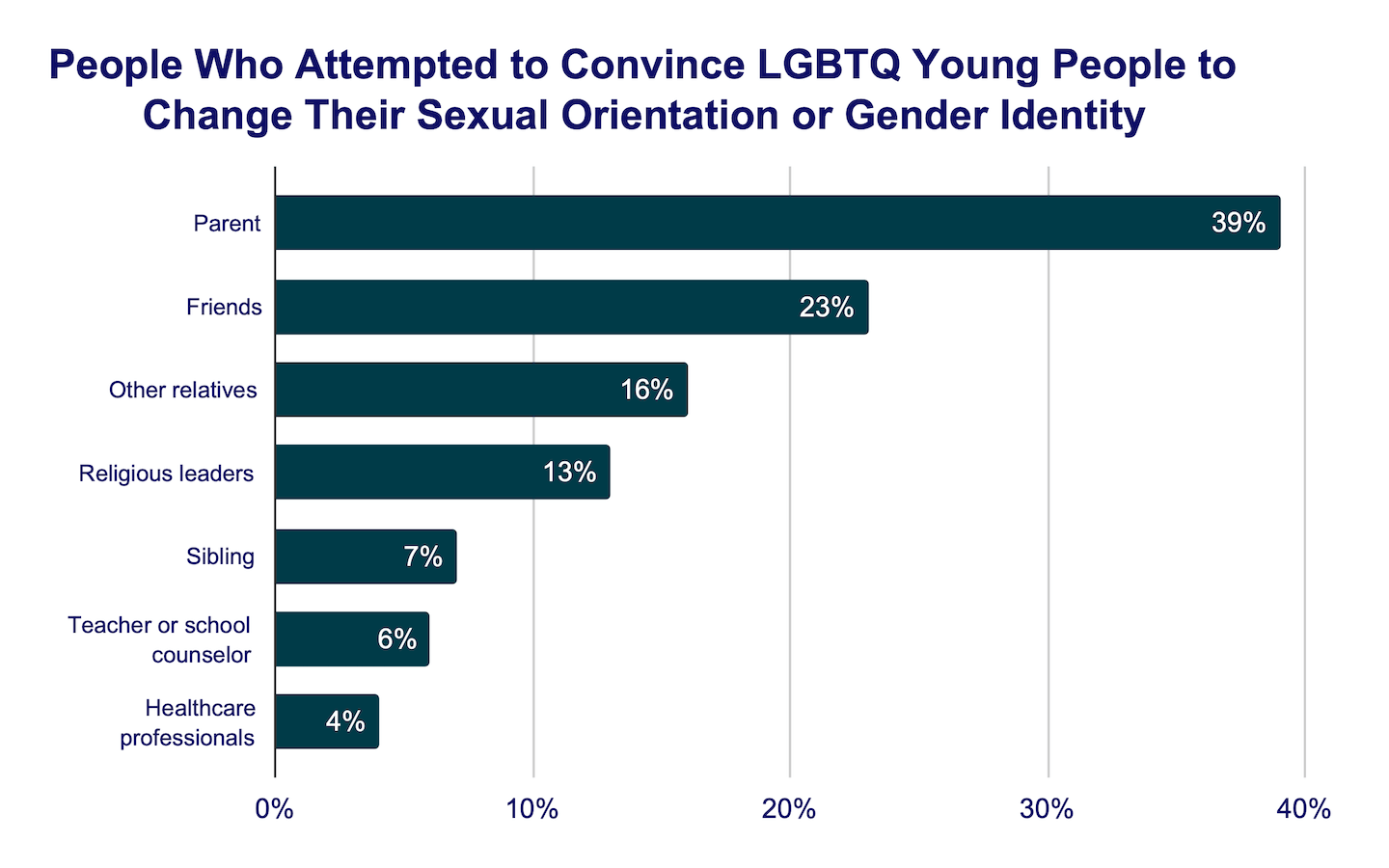

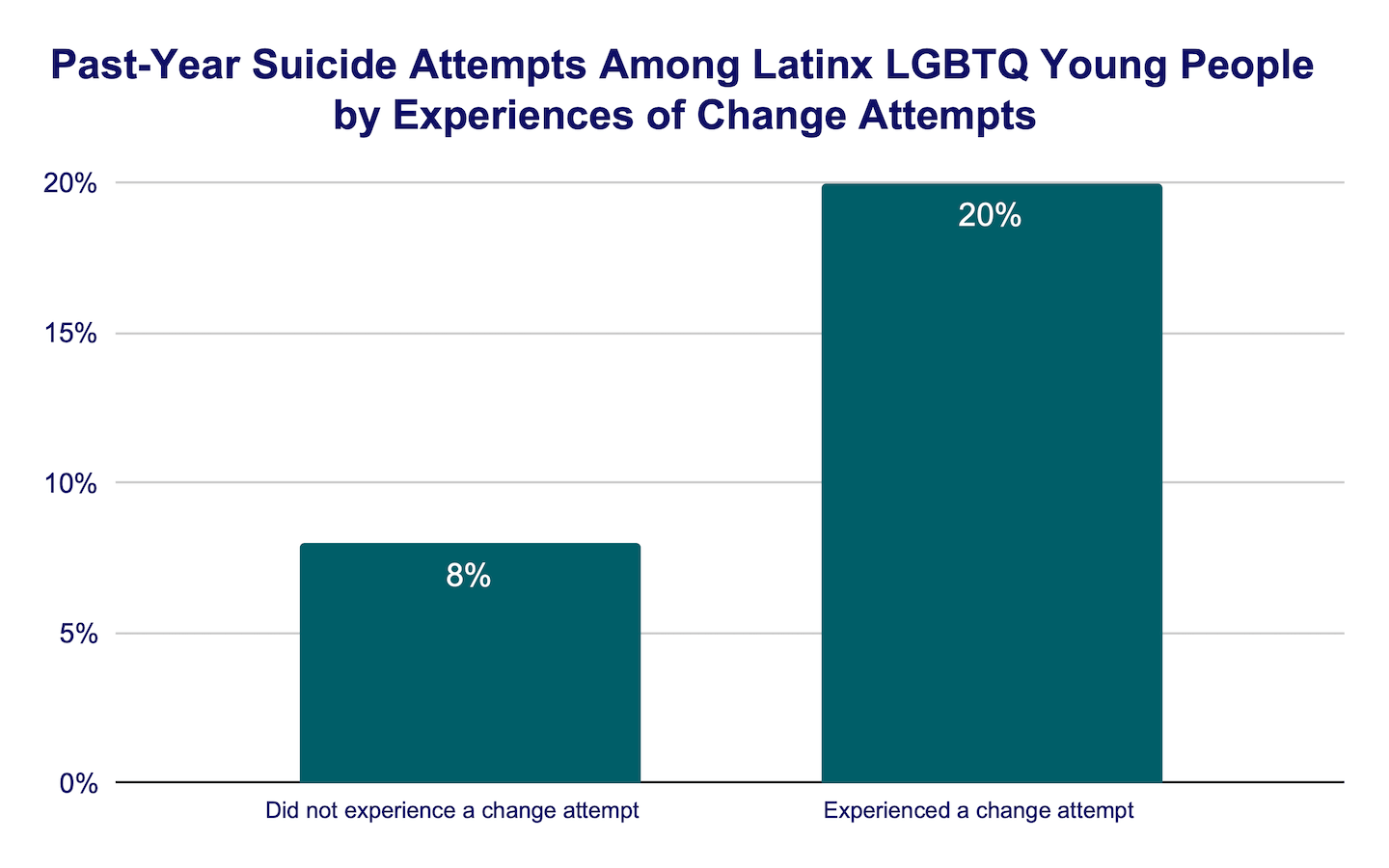

Alongside formal conversion therapy, many young people face other informal change attempts by individuals trying to persuade them to alter their sexual orientation and gender identity. In fact, three in five Latinx LGBTQ young people reported that someone tried to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity. The majority of these attempts came from parents (39%) and friends (23%). While the rate for change attempts among friends matched that of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people (23%), Latinx LGBTQ young people experienced a higher rate of change attempts from parents (39%) compared to the broader LGBTQ young sample (34%). Additionally, Latinx LGBTQ young people reported that other sources of change attempts included other relatives (16%), religious leaders (13%), siblings (7%), teachers or school counselors (6%), and healthcare professionals (4%). Latinx LGBTQ young who indicated that someone tried to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity reported nearly three times the rate of suicide attempts (20%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ who did not report experiencing these attempts (8%).

Structural Inequities

Economic stability, which encompasses both housing stability and food security, is one of the five social determinants of health identified by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) (ODPHP, 2020). This highlights the crucial influence factors on the overall well-being of young people.

Housing Instability

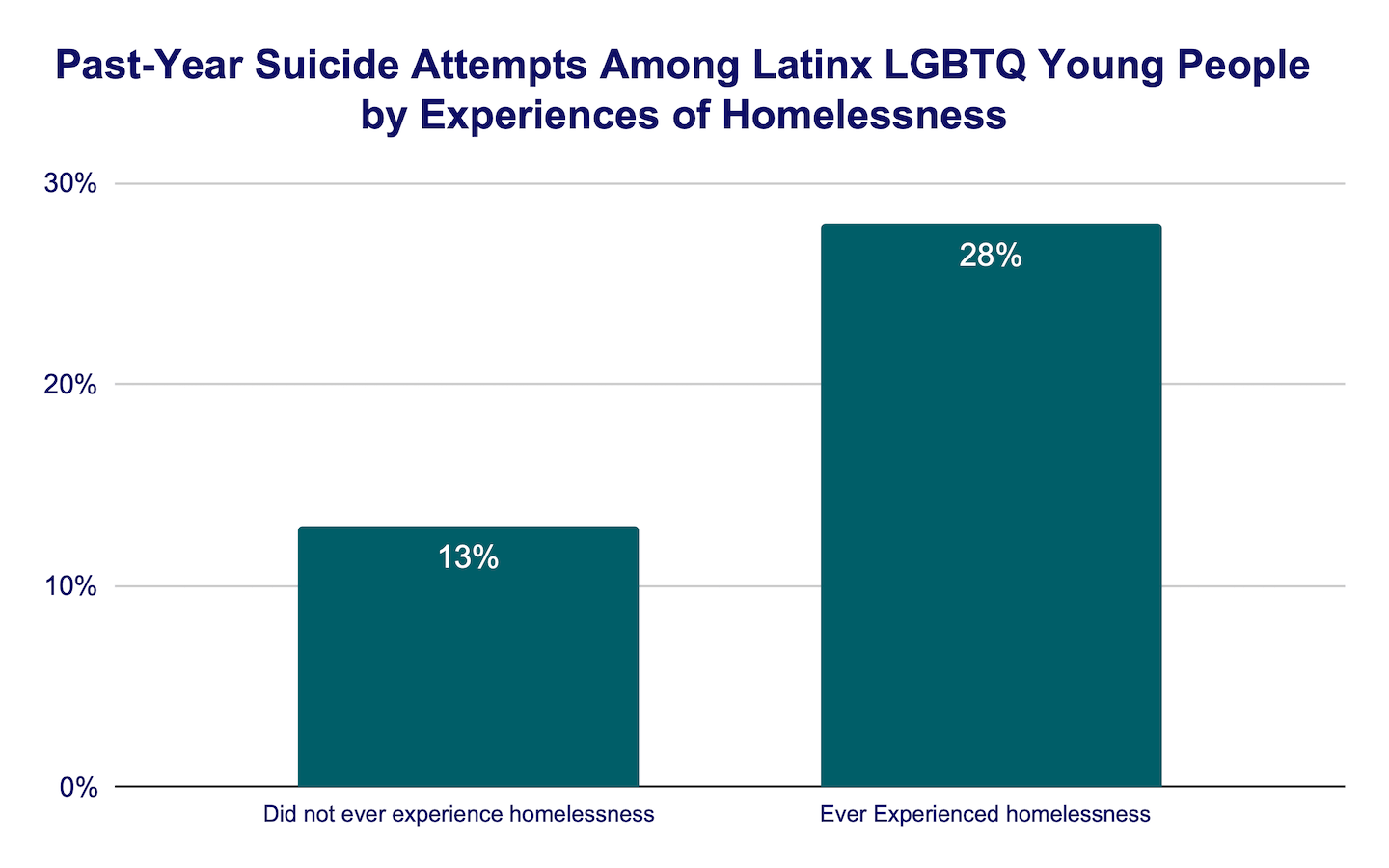

Among Latinx LGBTQ young people, 18% reported being currently or ever homeless. This is higher compared to the 16% of LGBTQ young people in the entire sample. Similar to other findings, multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of homelessness (22%) compared to exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people (15%), as did Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people (22%) compared to cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (13%). That said, Latinx young people aged 18 to 24, whose parents either face fewer legal repercussions for evicting them or who may have decided to leave home on their own, reported higher rates of homelessness (18%) compared to their younger counterparts aged 13 to 17 (14%). Latinx LGBTQ young people who were experiencing or had ever experienced homelessness reported attempting suicide in the past year at more than twice the rate (28%) of those who have not faced homelessness (13%).

Food Insecurity

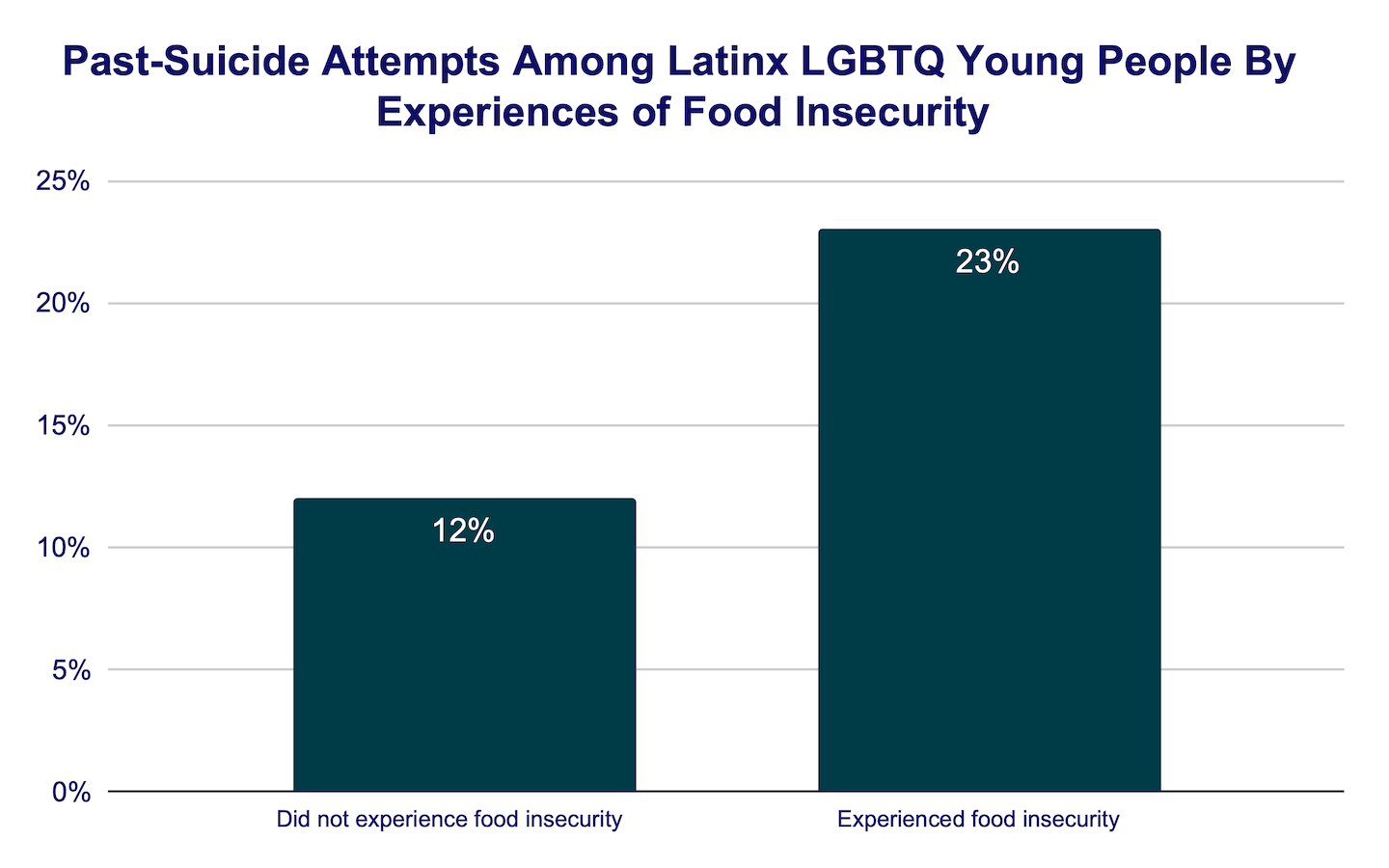

Food insecurity, defined as the disruption of food intake or eating patterns because of money or other resources (Yousefi-Rizi et al., 2021), was reported by 33% of Latinx LGBTQ young people in the past month compared to 29% of the entire sample. As with other findings, food insecurity was higher among multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people (36%) and Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people (39%) compared to exclusively Latinx (31%) and cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (26%). Likely related to higher rates of homelessness, Latinx LGBTQ young people ages 18 to 24 reported higher rates of food instability (34%) compared to their 13- to 17-year-old counterparts (27%). Latinx LGBTQ young people who reported food insecurity had nearly double the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (23%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ young people who did not (12%).

Discrimination Based on Multiple Identities

Latinx LGBTQ young people are vulnerable to discrimination and victimization based on several identities including, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual identity, and immigration status. All of the young people in our sample were asked about experiences of discrimination based on their actual or perceived identity in several different categories.

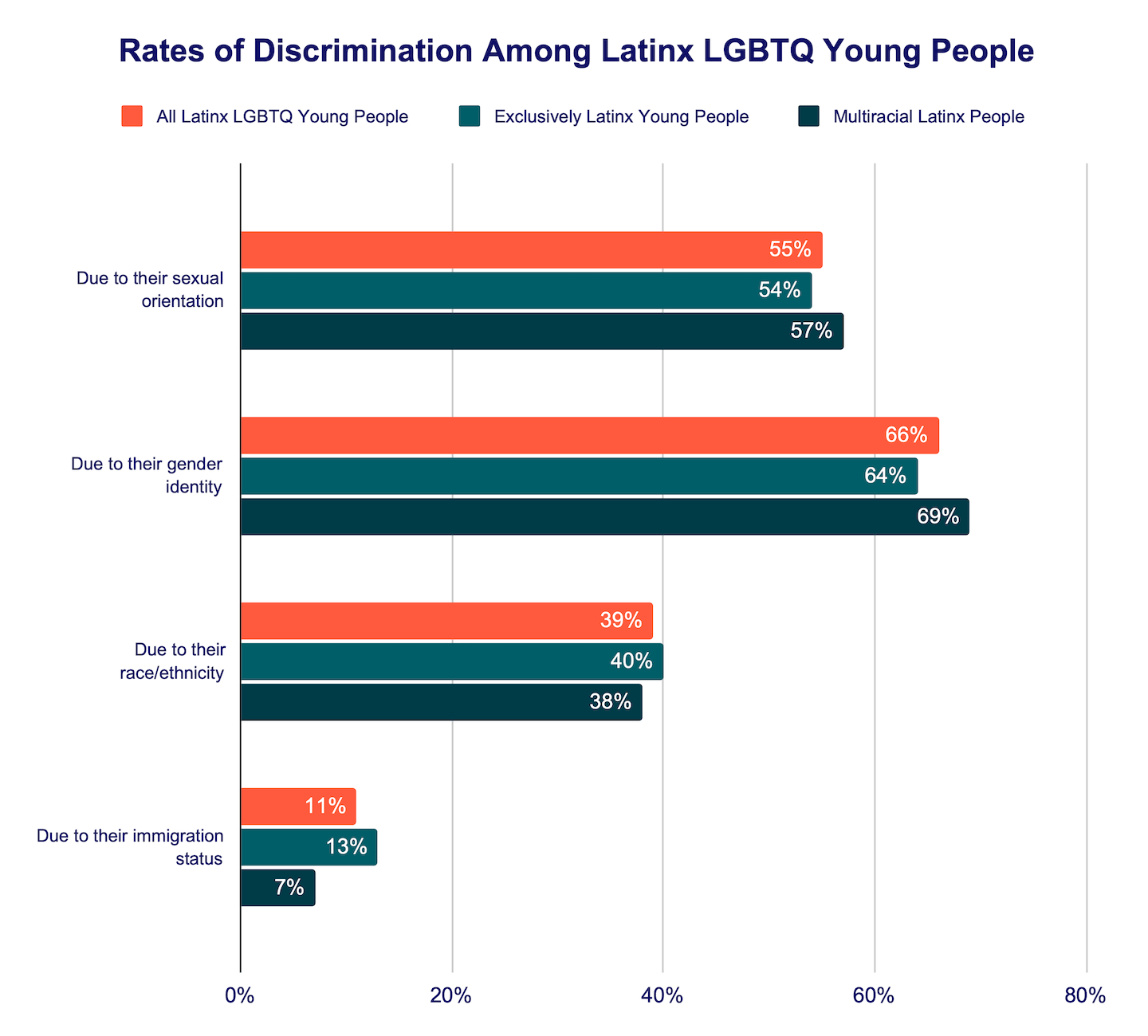

In our sample of Latinx LGBTQ young people, 39% reported experiencing discrimination based on their race/ethnicity in the past year. This includes 40% of exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people and 38% of multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people. For comparison, 25% of the entire sample of LGBTQ youth reported such discrimination. Over half (55%) of Latinx LGBTQ young people reported discrimination based on their sexual orientation in the past year. Among transgender and nonbinary Latinx youth, two in three (66%) reported past-year discrimination based on their gender identity. Likely because a higher proportion of multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people identify as transgender and nonbinary and/or multisexual, they reported higher rates of discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity (57% and 69%, respectively) compared to exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people (54% and 64%, respectively). Finally, 11% of Latinx LGBTQ young people reported having been discriminated against based on their actual or perceived immigration status, which was higher for exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people (13%) compared to multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people (7%). Comparatively, while rates of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity for Latinx LGBTQ youth aligned with the overall LGBTQ youth sample, discrimination based on race/ethnicity was notably higher. Moreover, discrimination based on immigration status was more than double.

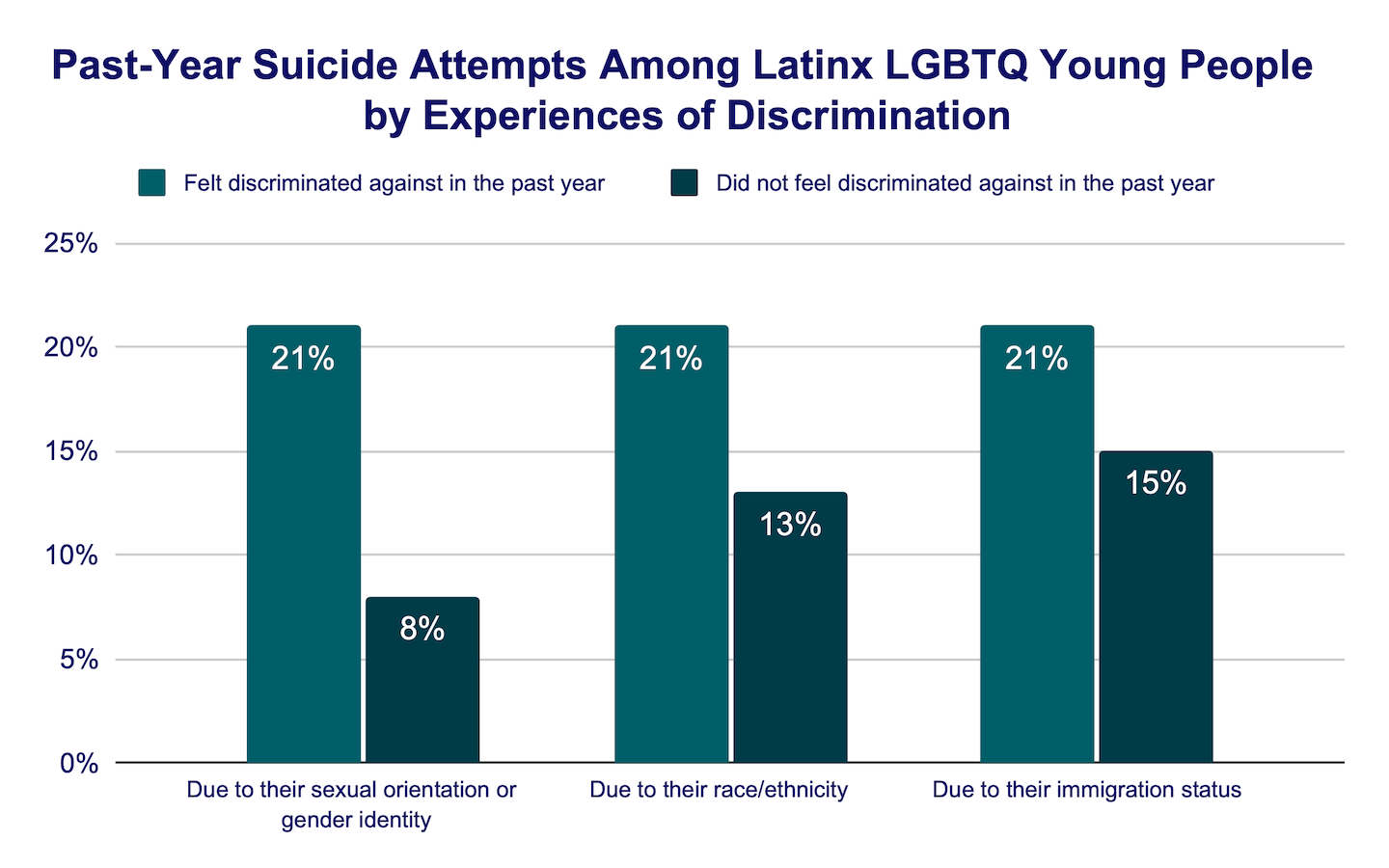

Among Latinx LGBTQ young people in our sample, those who experienced discrimination due to their sexual orientation or gender identity reported nearly three times the rate of suicide attempts in the past year (21%) compared to those who did not face such discrimination (8%).Those who faced immigration-based discrimination had higher rates of suicide attempts in the past year (21%) than their counterparts who did not experience this discrimination (15%). Similarly, Latinx LGBTQ young people reporting race-based discrimination showed a higher rate of suicide attempts in the past year (21%) compared to those who did not face racial discrimination (13%).

Victimization Based on Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity

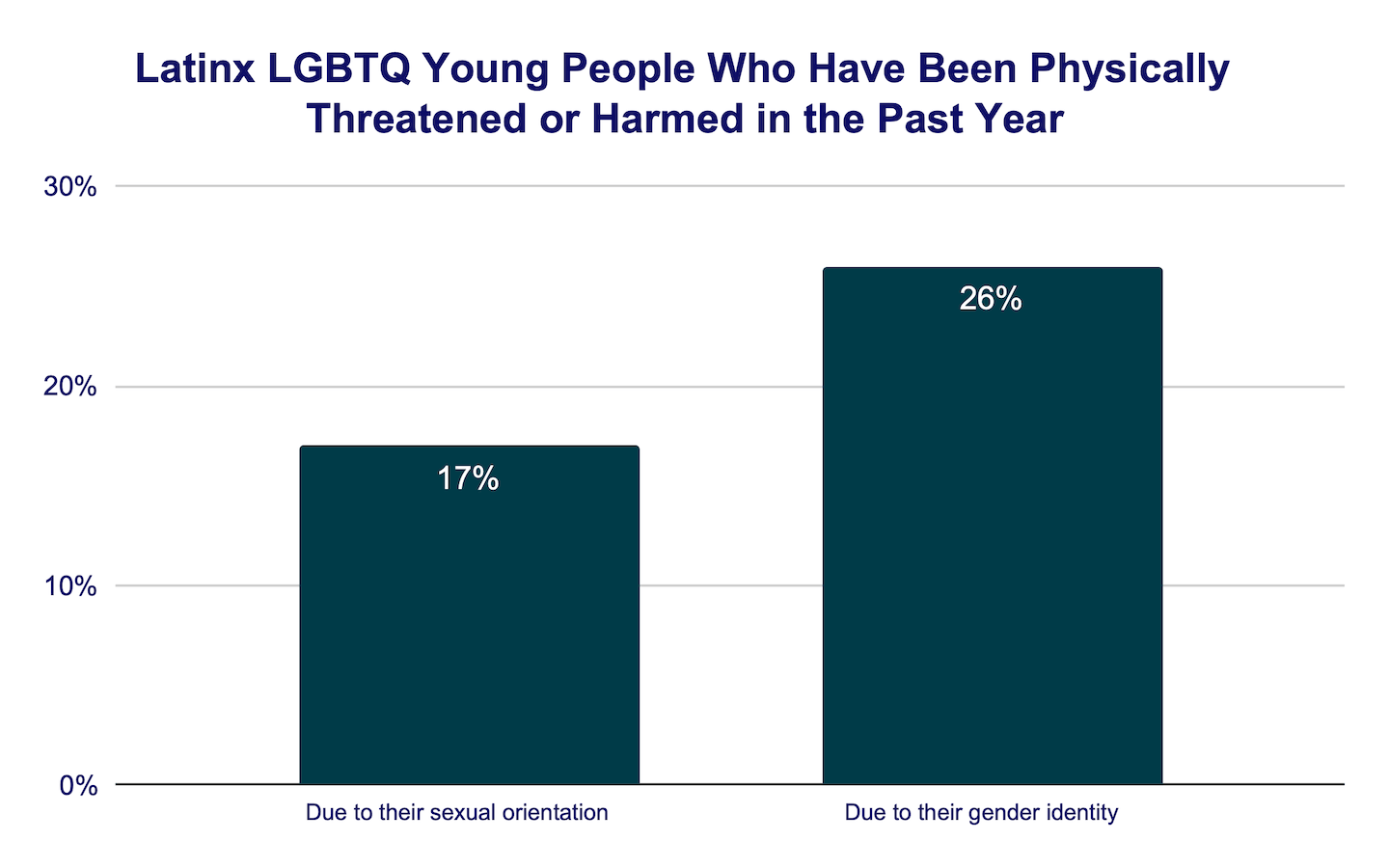

Overall, 23% of Latinx LGBTQ young people reported having been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year, which is similar to the broader sample of LGBTQ young people (24%). Of Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people, 26% experienced threats or physical harm based on their gender identity, while 17% of Latinx LGBTQ young people faced such threats or harms based on their sexual orientation. Additionally, multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of having been physically threatened or harmed due to their sexual orientation or gender identity (26%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ young people who did not identify as multiracial (20%).

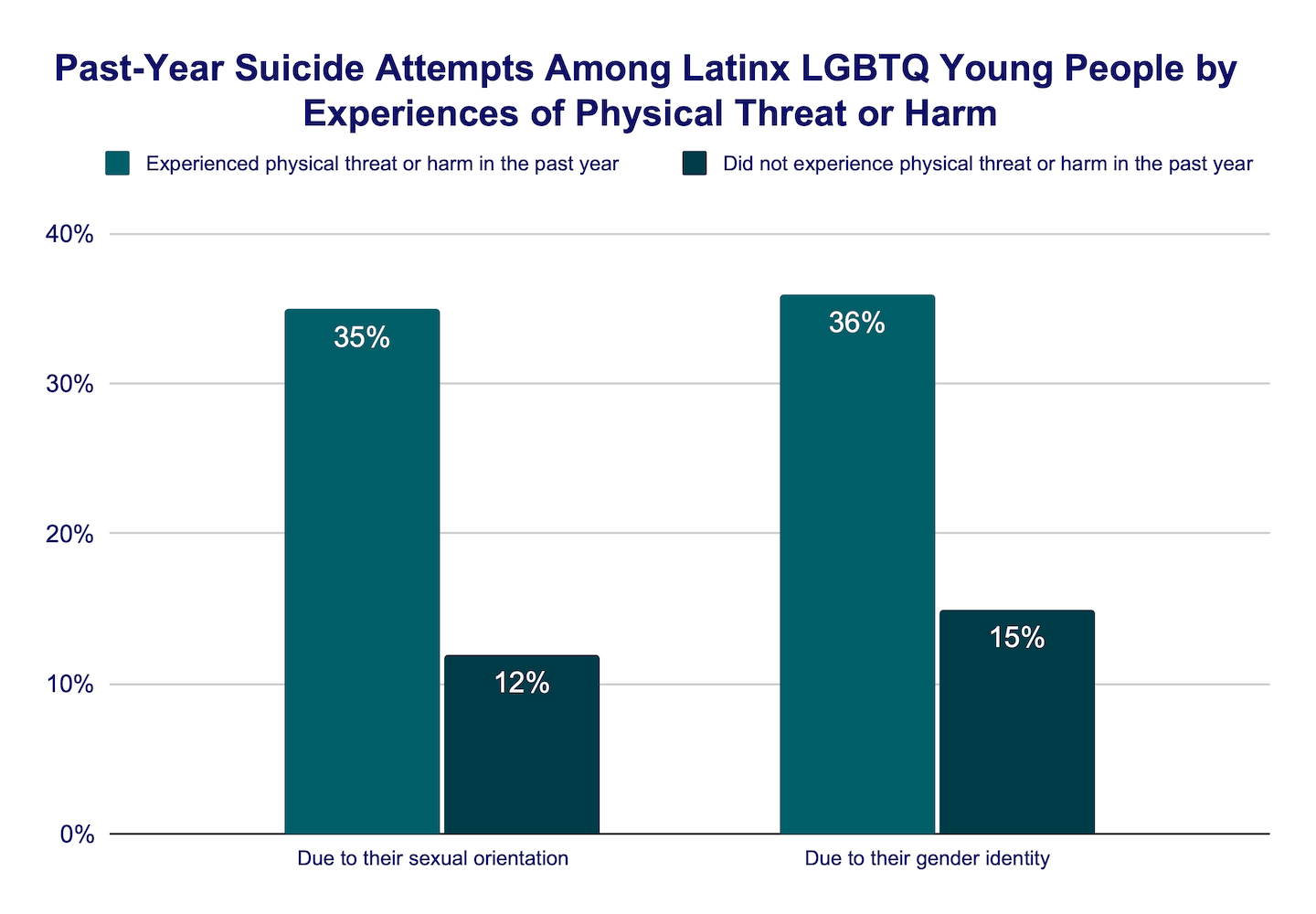

Latinx LGBTQ young people who had been physically harmed or threatened due to their sexual orientation or gender identity reported nearly three times the rate of past-year suicide attempts (32%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ young people who did not (11%).

Immigration Concerns

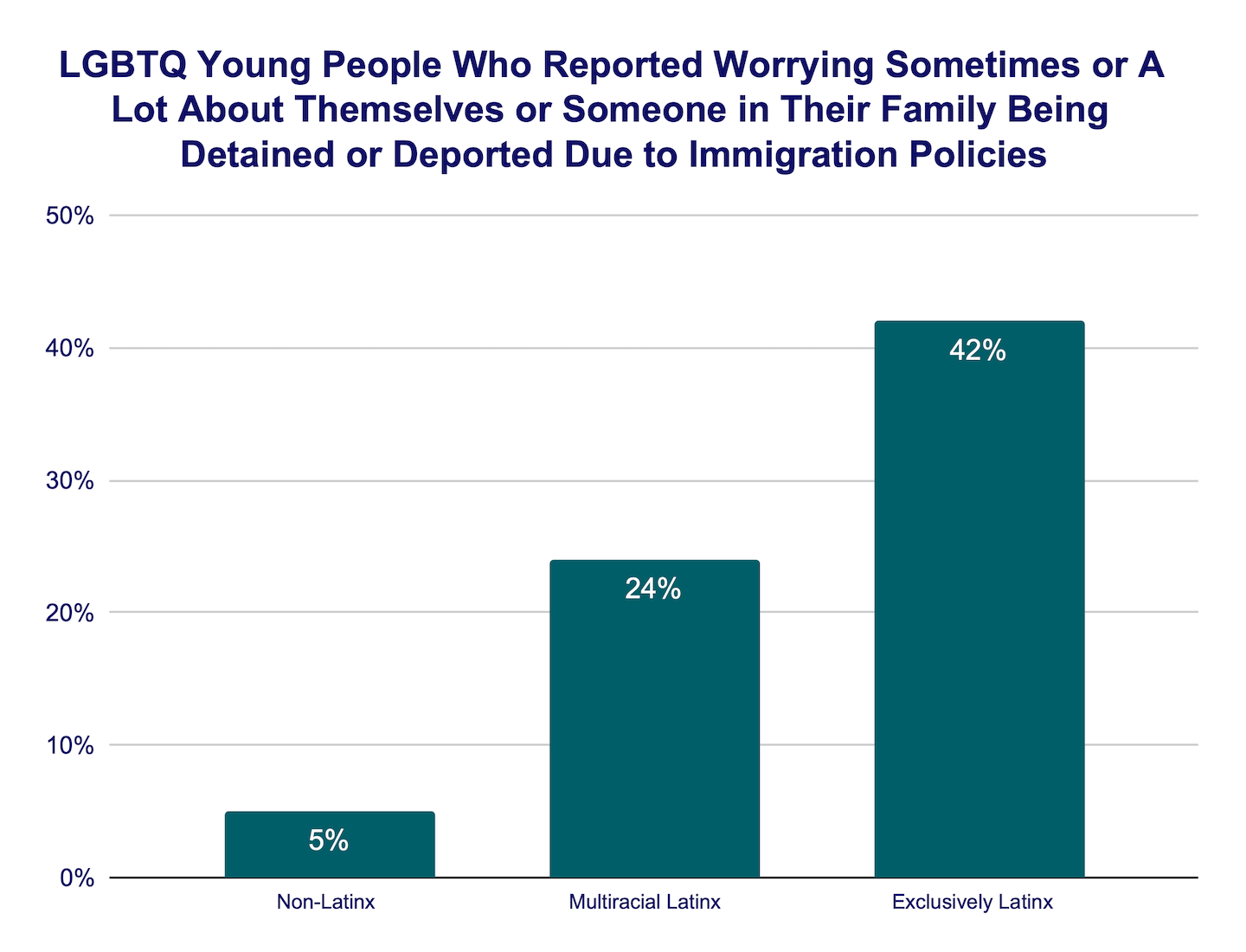

While Latinx communities are not the only ones to immigrate to the U.S., they often face negative attention directed at immigration. As aforementioned, 9% of the Latinx LGBTQ young people in our sample, and 52% of their parents, were born outside of the U.S. In contrast, our previous report (Price, et al., 2021) indicated that 15% of Asian American/Pacific Islander LGBTQ young people in the sample and 69% of their parents in our 2022 sample were born abroad. Although the immigration status of neither Latinx young people in the sample nor their parents directly correlated with mental health outcomes, a significant relationship between concerns about potential detention or deportation due to immigration policies and their mental health arose. Specifically, 34% of Latinx LGBTQ young people worried sometimes or a lot about themselves or a family member facing detainment or deportation due to immigration policies compared to only 5% of non-Latinx young people. Moreover, within the Latinx LGBTQ sample, disparities emerged based on racial identity. Exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people expressed higher levels of concern about immigration issues (42%) compared to their multiracial Latinx LGBTQ counterparts (24%).

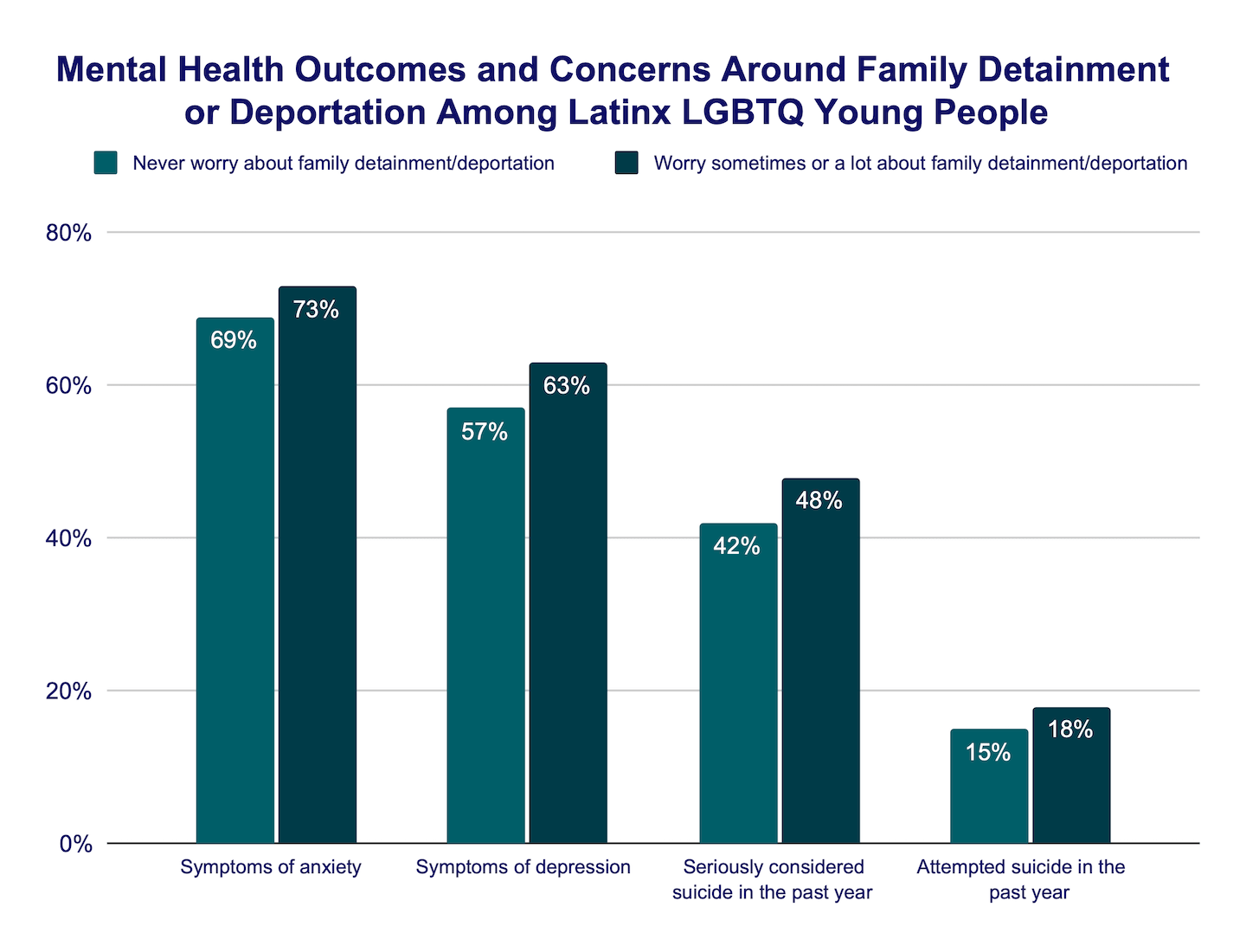

Latinx LGBTQ young people who worry sometimes or a lot about themselves or a family member facing detainment or deportation due to immigration policies reported higher rates of recent symptoms of anxiety (73%) and depression (63%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ youth who never worry about detainment or deportation (69% and 57%, respectively). They also reported higher rates of seriously considering suicide (48%) and attempting suicide in the past 12 months (18%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ young who did not have these concerns (42% and 15%, respectively). In addition, while Latinx LGBTQ young people had a 22% higher likelihood of attempting suicide in the past year compared to non-Latinx young people (aOR=1.22, 95% CI: 1.12-1.34), this difference disappeared when accounting for immigration worries (aOR=1.09, 95% CI: 0.99-1.20). This illustrates that the fear of personal or family detention or deportation is linked to a notably higher odds of suicide attempts among Latinx LGBTQ young people.

Protective Factors for Suicide Among Latinx LGBTQ Young People

Importance of Race

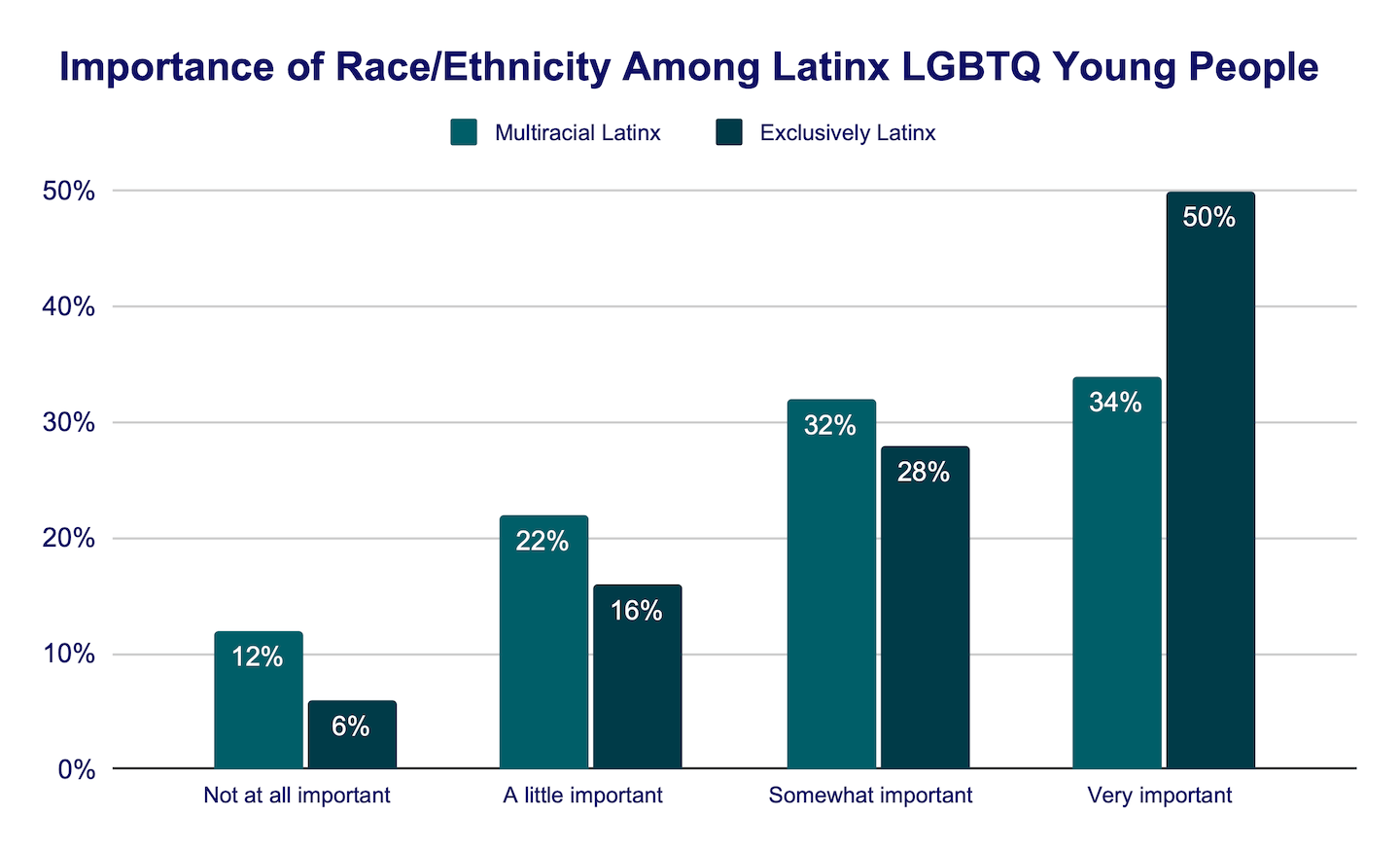

Despite the many stressors Latinx LGBTQ young people may face, they continue to find ways to thrive. Therefore, it is important to consider aspects of their lived experiences that help mitigate the risks they are up against. One such protective factor for Latinx young people is a strong connection to their cultural background (Przeworski & Piedra, 2020). As a proxy for this, all LGBTQ young people in our sample were asked if their race/ethnicity was an important part of who they are. More than two out of three (73%) Latinx LGBTQ young people stated that their race/ethnicity was a somewhat or very important part of who they were.

Latinx LGBTQ youth who felt that their race/ethnicity was an important part of who they were had 24% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year compared to Latinx LGBTQ young people who reported that their race/ethnicity was not at all or a little important to them (aOR= .76, 95% CI [.64, .89], p<.001). In general, the more important Latinx LGBTQ young people’s race/ethnicity was to who they were, the lower their rate of past-year suicide attempts. Importantly however, fewer multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people reported that their race/ethnicity was a somewhat or very important part of who they were (67%) compared to exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people (78%).

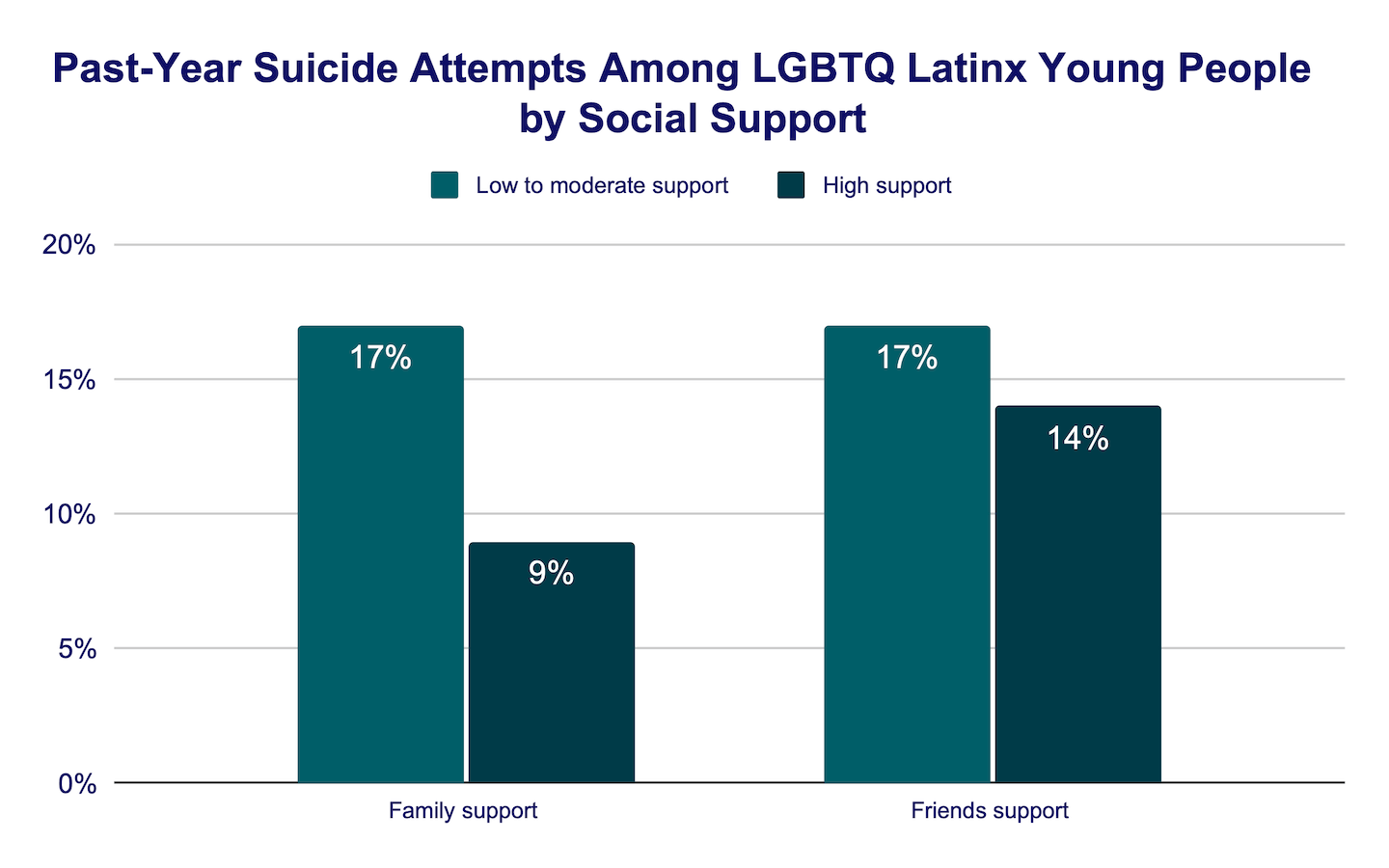

Supportive People

Social support is when family members and friends are present and helpful during times of need or when facing challenges. This kind of support was protective for Latinx LGBTQ young people in our sample. Latinx LGBTQ young people who reported high levels of family social support had about half the rate of attempting suicide in the past year (9%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ young people who did not report high family social support (17%). Additionally, Latinx LGBTQ young people with high levels of social support from friends reported lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year (14%) compared to those without such support (17%).

Despite the protectiveness of social support, only 21% of Latinx LGBTQ young people reported high levels of family social support. Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people reported lower rates of family support (16%) compared to cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (29%) as did Latinx young people ages 13 to 17 (17%) compared to Latinx young people ages 18 to 24 (27%). Furthermore, while Mexican LGBTQ young people reported significantly lower rates of social support from family (19%) compared to Puerto Rican LGBTQ young people (27%), Cuban LGBTQ young people’s rate of family support (22%) was not significantly different from either Mexican or Puerto Rican LGBTQ young people’s rates of family social support. That said, rates of social support from friends were higher among all Latinx LGBTQ young people (68%) compared to family social support. They were also higher for Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people (70%) compared to Latinx cisgender LGBQ young people (66%). Additionally, older Latinx LGBTQ young people (ages 18 to 24) reported higher rates of social support from friends (71%) compared to younger (ages 13 to 17) Latinx LGBTQ young people (65%).

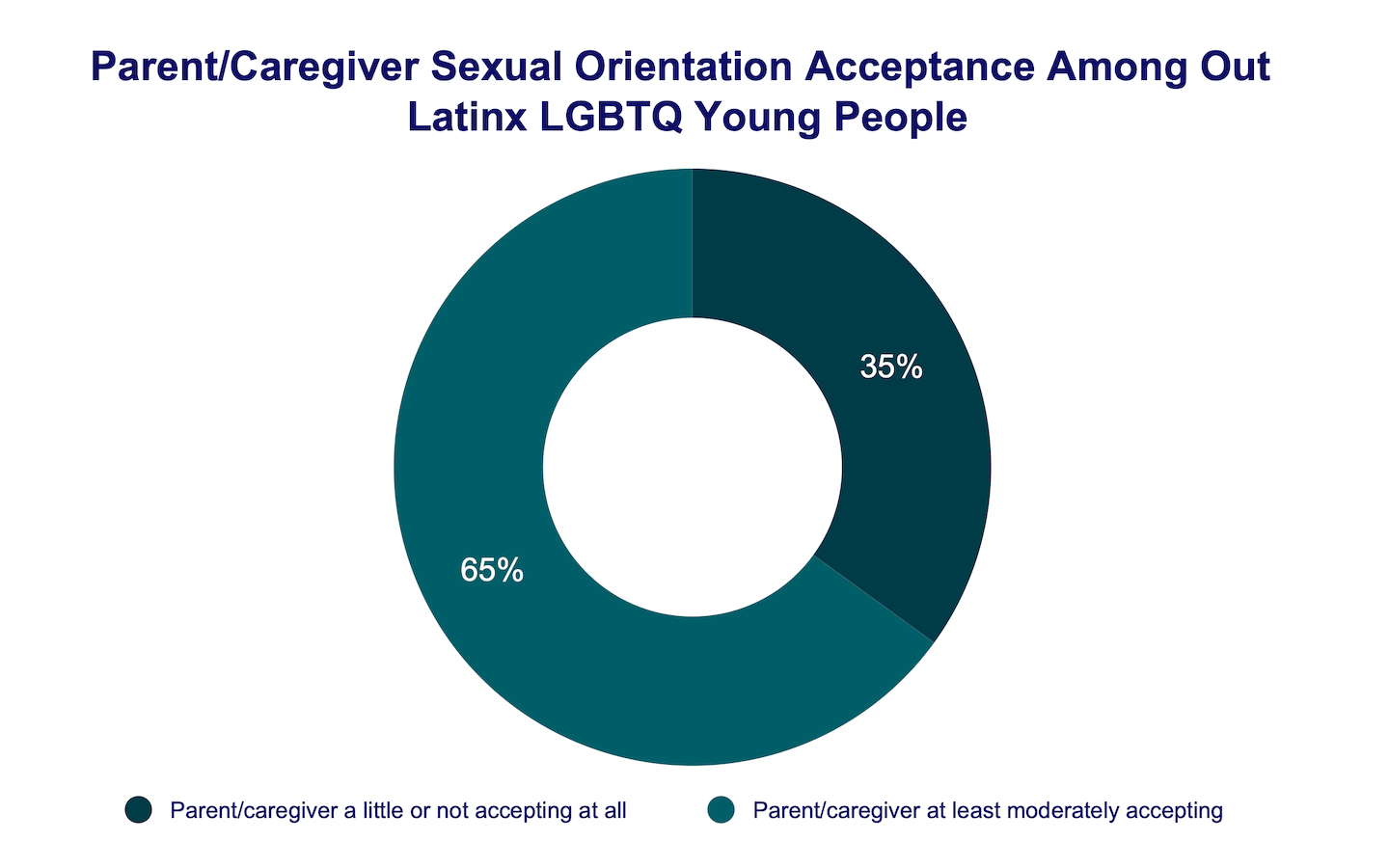

It is notable that general social support is different from LGBTQ acceptance, the latter of which can make youth feel specifically accepted and affirmed by others in their LGBTQ identities. Overall, 29% of Latinx LGBTQ young people were not out to parents or caregivers about their sexual orientation, which was comparable to 28% of the entire sample of LGBTQ young people. Among those who were out to a parent or caregiver about their sexual orientation, Latinx LGBTQ young people who had at least one parent who was accepting of their sexual orientation reported lower rates of past-year suicide attempts (16%) compared to Latinx LGBTQ young people whose parents or caregivers were not accepting of their sexual orientation (26%).

While Latinx LGBTQ young people reported low rates of family social support, 65% indicated that at least one parent or caregiver was accepting of their sexual orientation. These acceptance rates were higher among cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people (70%) compared to Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people (63%). Additionally, Latinx LGBTQ young people ages 18 to 24 reported higher sexual orientation acceptance (68%) compared to those aged 13 to 17 (63%). Finally, multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people reported higher acceptance (71%)compared to exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people (61%).

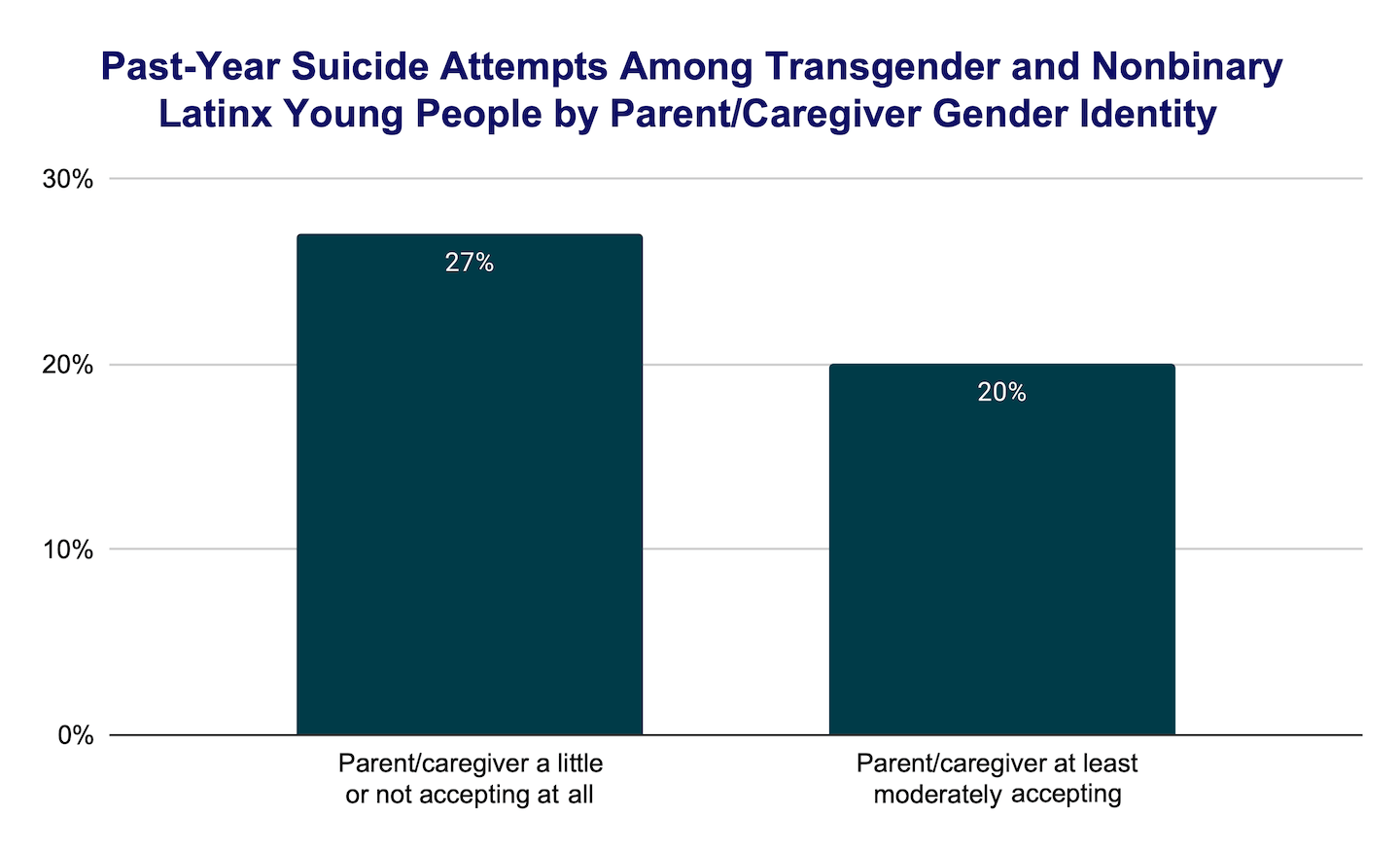

Additionally, 42% of Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people were not out to a parent or caregiver about their gender identity, compared to 40% of the overall sample of transgender and nonbinary young people. Similar to sexual orientation acceptance, among those who were out about their gender identity to their parent/caregiver, Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people who had at least one parent who was accepting of their gender identity also reported lower rates of past-year suicide attempts (20%) compared to those without accepting parents (27%).

While nearly two in three Latinx LGBTQ young people reported their parent or caregiver was supportive of their sexual orientation, less than half of Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people reported their parent or caregiver was accepting of their gender identity (46%). The rates of gender identity support were higher among multiracial Latinx young people (49%) compared to exclusively Latinx young people (43%), and Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people ages 18 to 24 (49%) compared to those ages 13 to 17 (44%).

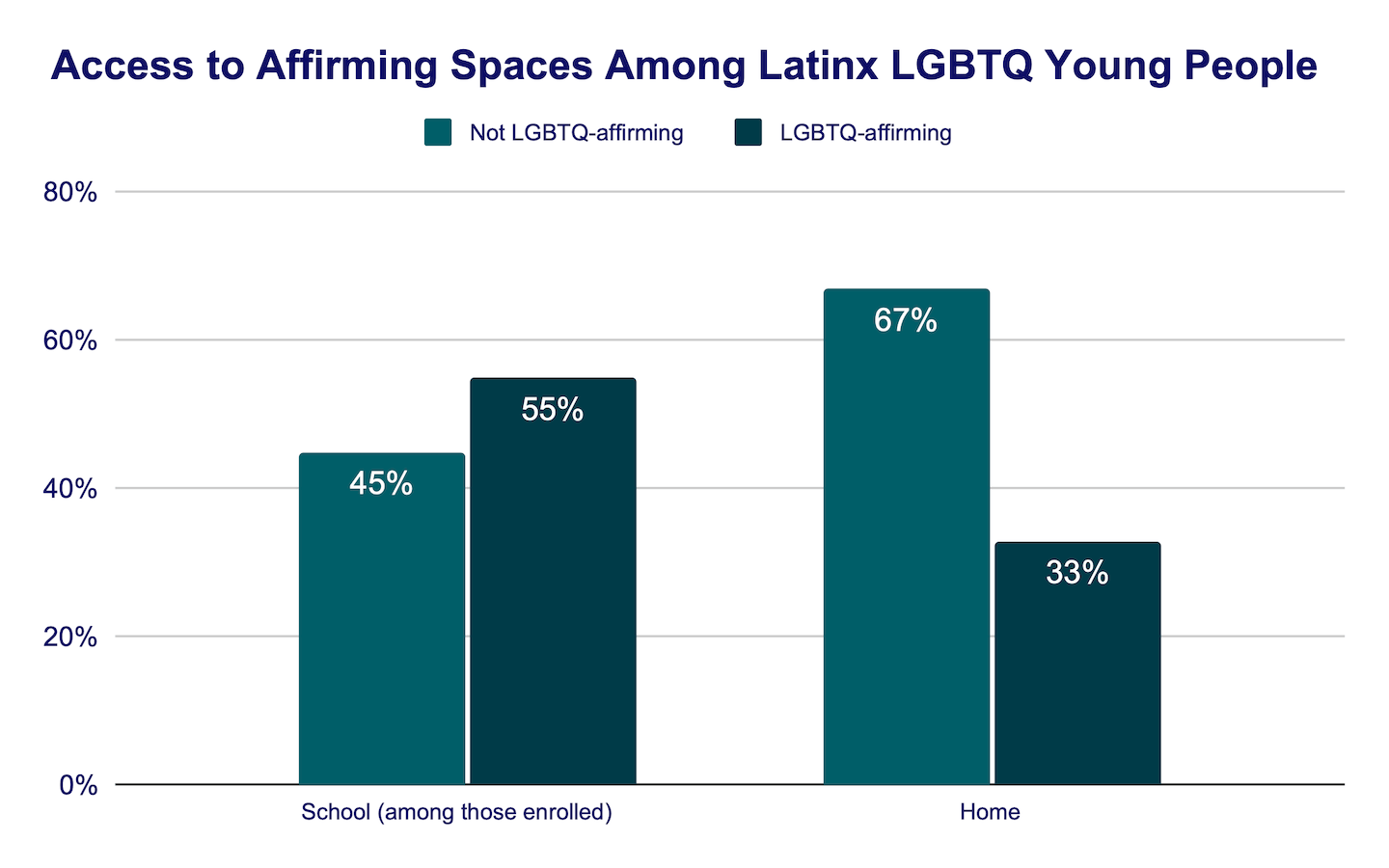

Supportive Places

For Latinx LGBTQ young people, having access to LGBTQ affirming spaces was associated with lower rates of suicide attempts. Overall, 55% of Latinx LGBTQ students reported their school was LGBTQ-affirming, including 58% of cisgender Latinx LGBQ young people and 54% of Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people.

Latinx LGBTQ young people who attended LGBTQ-affirming schools reported lower rates of suicide attempts in the past year (13%) compared to those who did not attend such schools (18%). Similarly, those who lived in LGBTQ-affirming homes had a lower rate of past-year suicide attempts (13%) compared to those living in non-affirming homes (17%). However, only 33% of Latinx LGBTQ young people said they lived in an LGBTQ-affirming home. These rates were even lower for Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people (31%) when compared to Latinx cisgender LGBQ young people (44%). In addition, 29% of exclusively Latinx LGBTQ young people lived in an LGBTQ affirming home which is less than that of multiracial Latinx LGBTQ young people (38%). Similarly, only 26% of 13-17-year-old Latinx LGBTQ young people reported living in LGBTQ-affirming homes, in contrast to 45% of those aged 18 to 24 years.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Latinx LGBTQ young people have diverse identities, experiences, and needs. Their unique circumstances demand attention from various stakeholders to improve their mental health outcomes. The current findings show that Latinx LGBTQ young people are diverse in regard to sexual orientation, gender identity, and background, both within their own group and compared to other LGBTQ young people. While their sexual and gender identities mirrored those of the general LGBTQ youth population, Latinx LGBTQ young people report higher rates of mental health challenges such as anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicidal ideation. Specifically, they have a 22% higher odds of attempting suicide in the past year compared to non-Latinx LGBTQ young people. These heightened rates can be attributed to common risk factors faced by LGBTQ young people, such as discrimination and physical threats or harms based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Additionally, Latinx LGBTQ young people encounter unique stressors stemming from their dual minority identity (Latinx and LGBTQ), such as racial discrimination, systemic inequities, and issues related to immigration. Currently, 60% of Latinx LGBTQ youth in our sample were unable to access the mental health care they desired. This underscores the urgent need for increased investment in their mental health and well-being. Given the protectiveness of culture and family support, programs aimed at suicide prevention and treatment should be culturally relevant, reflect the intercultural strengths of this community, and be linguistically accessible. It is also vital to offer resources and support for parents, families, and valued community members to better support the well-being of Latinx LGBTQ young people.

Latinx LGBTQ young people are not a homogenous group; important disparities exist within this group that need consideration when allocating resources. While our study did not have the sample size to consider important within-group differences by country of origin or race (e.g., Afro-Latinx), we identified significant disparities by gender identity and age. With 21% of transgender and nonbinary Latinx young people attempting suicide in the past year, their mental health is a serious public health concern that demands immediate attention. Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people face challenges related to their sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity, particularly as they navigate expectations related to machismo and marianismo, while also being confronted with stressors faced by all young people regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity, such as passing a final exam. Moreover, Latinx LGBTQ individuals between the ages of 13 to 17 are especially vulnerable to mental health issues, often exacerbated by limited support from family and friends and difficulties accessing desired mental health care. The convergence of these developmental challenges and inadequate support is deeply concerning. Targeted attention and prevention programs are essential for Latinx transgender and nonbinary young people, and/or those who are 13 to 17 years old in order to address their distinct challenges and experiences.

Suicide intervention and prevention programs for Latinx LGBTQ young people must factor in key contextual elements of their environment. The influence of one’s surroundings and societal policies can profoundly affect one’s well-being (Alegria et al., 2018; Hatzenbuehler, 2010). For instance, we found that the fear of personal or family detention or deportation is linked to a notably higher odds of suicide attempts among Latinx LGBTQ young people. Importantly, the increased odds of suicide between Latinx LGBTQ young people and non-Latinx LGBTQ young people disappeared after adjusting for the impact of these worries. Thus, to effectively reduce this suicide risk, interventions must address immigration concerns among Latinx LGBTQ young people. This could involve supporting young people and their families in navigating the legal system or assisting with citizenship or legal residency processes. LGBTQ organizations should adopt a decolonizing and anti-racist stance to truly support Latinx young people, while Latinx organizations need to affirm and support LGBTQ identities. Lastly, to counteract the heightened suicide risks associated with structural inequities, prevention strategies must tackle economic challenges and discriminatory practices threatening Latinx families.

There is a pressing need to address the research gaps that fail to accurately capture the experiences of Latinx LGBTQ young people. There is a serious lack of health research with Latinx participants (Sage et al., 2019). Historical transgressions, such as the unethical birth control drug trial on Puerto Rican women in 1955 (Blake, 2018), have understandably fostered mistrust of research within the Latinx community. Moreover, current U.S. immigration policies pose additional hurdles for research participation and retention. However, one of the main ways to address mental health inequities is through collecting quality data; therefore, the research community must do better to explore and document Latinx LGBTQ young people’s experiences. Large-scale national studies, which have the sample size to perform advanced analyses and draw rigorous conclusions, should be used to examine outcomes specific to Latinx LGBTQ young people. Upcoming research initiatives should prioritize forging robust ties with the Latinx community, and interventions should be co-designed with community partners, especially Latinx young people. Institutions of higher education should champion diversity in their programs, ensuring access to Latinx LGBTQ researchers for young people. Finally, researchers should prioritize the broad dissemination of their findings on Latinx LGBTQ youth — from easily accessible online summaries to presentations for organizational leaders — ensuring a wide array of stakeholders benefit from the insights.

The Trevor Project is devoted to improving the mental health and well-being of Latinx LGBTQ young people. The Trevor Project’s mission of ending suicide among LGBTQ young people necessarily understands that a “one-size-fits-all” approach does not work. Included in the Trevor Project’s existing efforts to uplift the voices and experiences of Latinx LGBTQ young people are our celebrations of Latinx Heritage Month and our previous brief exploring Latinx LGBTQ Youth Suicide Risk. As The Trevor Project Mexico marks its first year of operations supporting LGBTQ young people in Mexico, our crisis services teams aim to provide all LGBTQ youth with high-quality, culturally-grounded care, working together to ensure our diverse team of counselors and staff aligns with the demographics of the youth we serve. Additionally, our research team will continue existing efforts to explore and disseminate findings specific to Latinx LGBTQ young people to support a better understanding of their unique experiences and address the mental health and well-being of Latinx LGBTQ young people.

| The authors of this report acknowledge and extend our deepest thanks to Hannah R. Rosen, for providing support on the creation of this report. |

About The Trevor Project

The Trevor Project is the leading suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, & questioning (LGBTQ) young people. The Trevor Project offers a suite of 24/7 crisis intervention and suicide prevention programs, including TrevorLifeline, TrevorText, and TrevorChat as well as the world’s largest safe space social networking site for LGBTQ youth, TrevorSpace. Trevor also operates an education program with resources for youth-serving adults and organizations, an advocacy department fighting for pro-LGBTQ legislation and against anti-LGBTQ policies, and a research team to examine the most effective means to help young LGBTQ people in crisis and end suicide. If you or someone you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386, via chat TheTrevorProject.org/Help, or by texting 678-678.

This report is a collaborative effort from the following individuals at The Trevor Project:

Myeshia N. Price, PhD

Director of Research Science

Ronita Nath, PhD

Vice President of Research

Jonah P. DeChants, PhD

Senior Research Scientist

Steven Hobaica, PhD

Research Scientist

Kasey Suffredini

Interim Senior Vice President of Prevention

Recommended Citation: Price, M.N., Nath, R., DeChants, J.P., Hobaica, S., Suffredini, K.(2023). The Mental Health and Well-Being of Latinx LGBTQ Young People. The Trevor Project.

Media inquiries:

[email protected]

Research-related inquiries:

[email protected]

REFERENCES

- Alegría, M., NeMoyer, A., Falgàs Bagué, I., Wang, Y., & Alvarez, K. (2018). Social determinants of mental health: where we are and where we need to go. Current psychiatry reports, 20, 1-13.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0969-9 - Arevalo, S. (2023, May 16). Latino, Latinx, Latine or Hispanic: Fenton’s Guidance on How to Reference People of Latin American Descent. LinkedIn.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/latino-latinx-latine-hispanic-fentons-guidance-how - Baams, L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038994 - Barrera, I., & Longoria, D. (2018). Examining cultural mental health care barriers among Latinos. Journal for Leadership, Equity, and Research, 4(1).

- Blakemore, E. (2018, May 9). The first birth control pill used Puerto Rican women as guinea pigs. History.com.

https://www.history.com/news/birth-control-pill-history-puerto-rico-enovid - Brooks VR: Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1981.

- Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

- Falicov, C. J. (2014). Psychotherapy and supervision as cultural encounters: The multidimensional ecological comparative approach framework.

- Feagin, J. R., & Cobas, J. A. (2015). Latinos facing racism: Discrimination, resistance, and endurance. Routledge.

- Forsythe, A., Pick, C., Tremblay, G., Malaviya, S., Green, A., & Sandman, K. (2022). Humanistic and economic burden of conversion therapy among LGBTQ youths in the United States. JAMA pediatrics, 176(5), 493-501.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0042 - Gattamorta, K. A., Salerno, J., & Quidley-Rodriguez, N. (2019). Hispanic parental experiences of learning a child identifies as a sexual minority. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 15(2), 151–164.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2018.1518740 - Gaylor, E.G., Krause, K.H., Welder, LE., Cooper, A.C., Ashley, C., Mack, K.A., Crosby, A.E., Trinh, E., Ivey-Stephenson, A.Z., Whittle, L. (2023). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among high school students —Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 72, 45-54.

- Gonzalez, M., Connaughton-Espino, T., & Reese, B.M. (2023). “A little harder to find your place:” Latinx LGBTQ youth and family belonging. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 35(3), 271-297.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2022.2058143 - Green, A. E., Price, M. N., & Dorison, S. H. (2022). Cumulative minority stress and suicide risk among LGBTQ youth. American journal of community psychology, 69(1-2), 157-168.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12553 - Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2010). Social factors as determinants of mental health disparities in LGB populations: Implications for public policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 4(1), 31-62.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2010.01017.x - Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Underwood, J. M.(2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students — 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3 - Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3 - Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., Truong, N. L., & Zongrone, A. D. (2020). The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN.

https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/NSCS-2019-Full-Report_0.pdf - Massey DS. Racial formation in theory and practice: The case of Mexicans in the United States. Race and Social Problems. 2009;1(1):12–26.

- McGee, V. (2023, July 18). Latino, Latinx, Hispanic, or Latine? Which Term Should You Use? BestColleges. https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/hispanic-latino-latinx-latine/

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 - Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Social determinants of health. Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

https://health.gov/healthypeople - Pellicane, M. J., & Ciesla, J. A. (2022). Associations between minority stress, depression, and suicidal ideation and attempts in transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 91, 102113.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102113 - Perreira, K. M., Marchante, A. N., Schwartz, S. J., Isasi, C. R., Carnethon, M. R., Corliss, H. L., Kaplan, R. C., Santisteban, D. A., Vidot, D. C., Van Horn, L., & Delamater, A. M. (2019). Stress and Resilience: Key correlates of mental health and substance use in the Hispanic community health study of Latino youth. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 21(1), 4–13.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0724-7 - Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005 - Price, M. N., DeChants, J. P., & Davis, C. K. (2022).The mental health and well-being of multiracial LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

- Price, M. N., Green, A. E., DeChants, J. P., & Davis, C. K. (2021).The mental health and well-being of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

- Price-Feeney, M, Green, A.E. & Dorison, S. (2020). All Black lives matter: Mental health of Black LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

- Price-Feeney, M., Green, A. E., & Dorison, S. (2020). Understanding the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), 684–690.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.11.314 - Przeworski, A., & Piedra, A. (2020). The role of the family for sexual minority Latinx individuals: A systematic review and recommendations for clinical practice. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 16(2), 211–240.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2020.1724109 - Perez-Escamilla, R. (2010). Health care access among Latinos: implications for social and health care reforms. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 9(1), 43-60.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192709349917 - Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 126(6), 1117–1123.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0852 - Ryan, C., S. T. Russell, D. Huebner, R. Diaz, and J. Sanchez. 2010. “Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 23(4): 205–213.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x - Sage, R., Benavides-Vaello, S., Flores, E., LaValley, S., & Martyak, P. (2018). Strategies for conducting health research with Latinos during times of political incivility. Nursing open, 5(3), 261–266.

https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.166 - Schmitz, R.M., Robinson, B.A., Tabler, J., Welch, B, & Rafaqut, S (2019). LGBTQ+ Latino/a young people’s interpretations of stigma and mental health: An intersectional minority stress perspective. Society and Mental Health, 1-17.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869319847248 - Schmitz, R.M., Sanchez, J., Lopez, B. (2019).LGBTQ+ Latinx young adults’ health autonomy in resisting cultural stigma. Culture, Health, & Sexuality, 21(1): 16-30.

- Silva, C., & Van Orden, K. A. (2018). Suicide among Hispanics in the United States. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 44–49.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.013 - Stein, G.L., Gonzalez, L.M., Cupito, A.M., Kiang, L., & Supple, A.J. (2015). The protective role of familism in the lives of Latino adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 36, 1255–1273.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13502480 - Valentín-Cortés, M., Benavides, Q., Bryce, R., Rabinowitz, E., Rion, R., Lopez, W. D., & Fleming, P. J. (2020). Application of the minority stress theory: Understanding the mental health of undocumented Latinx immigrants. American Journal of CommunityPsychology, 66(3–4), 325–336.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12455 - Yousefi-Rizi, L., Baek, J. D., Blumenfeld, N., & Stoskopf, C. (2021). Impact of housing instability and social risk factors on food insecurity among vulnerable residents in San Diego County. Journal of Community Health, 46, 1107–1114.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-00999-w - Zongrone, A. D., Truong, N. L., & Kosciw, J. G. (2020). Erasure and resilience: The experiences of LGBTQ students of color, Latinx LGBTQ youth in U.S. schools. New York: GLSEN.

| Table 1: Latinx LGBTQ Young People Characterics | |||

| Age (n =6,867) | Race and Ethnicity (n =6,867 ) | ||

| Under 18 | 64% | Multiracial Latinx (inclusive of other races) | 44% |

| 18 and over | 36% | Exclusively Latinx | 56% |

| Sex Assigned at Birth (n=) | Mexican | 28% | |

| Female | 83% | Puerto Rican | 5% |

| Male | 17% | Cuban | 2% |

| Sexual Orientation (n =6,832 ) | Colombian | 1% | |

| Bisexual | 29% | Another Latinx | 8% |

| Pansexual | 20% | Multiracial Latinx (not inclusive of other race/ethnicities) | 12% |

| Lesbian | 15% | Pronouns (n = 6,817) | |

| Gay | 11% | He/Him or She/Her only | 46% |

| Queer | 11% | Pronouns outside of the gender binary | 54% |

| Asexual | 9% | Speaks a language other than English at home (n=6,845 ) | 26% |

| I am not sure | 4% | Just meeting basic needs or less (n = 6,271) | 24% |

| Straight | 1% | U.S. Immigrant Status (n =6,791) | |

| Gender Identity (n =6,580) | Youth born outside of the U.S. | 9% | |

| Nonbinary | 37% | At least one parent/caregiver born outside of the U.S. | 52% |

| Cisgender woman | 28% | Region (n =6,831) | |

| Cisgender man | 10% | South | 40% |

| Transgender man | 15% | Midwest | 13% |

| Questioning | 8% | West | 35% |

| Transgender woman | 2% | Northeast | 13% |