Youth's Lives Every Day

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Trevor Project is a remote organization with staff and volunteers located across the land now known as the United States and Mexico. These lands are the traditional and ancestral homelands of countless Indigenous communities who were violently displaced by European settler colonialism. Despite enduring centuries of oppression and exploitation, Indigenous people continue to thrive – stewarding their lands and relations, nurturing their traditional knowledge and practices, and healing from historical and contemporary traumas.

We encourage readers to continue building their knowledge of Indigenous communities and cultures. Take a moment to learn the original names and the first peoples of your own local community, and to engage with the work of Indigenous scholars and researchers.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Indigenous LGBTQ young people face numerous social threats that can harm their overall mental health and well-being, including the historical and ongoing impact of colonization and anti-LGBTQ sentiments. Despite this, significant gaps in research persist due to the underrepresentation of Indigenous young people in U.S. studies. The failure to obtain adequate sample sizes to examine the unique experiences of Indigenous LGBTQ young people perpetuates inequities and inhibits progress toward dismantling structural forces that continue to oppress them. This report uses data from a national sample of nearly 2,000 Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 24 who participated in The Trevor Project’s 2023 National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People to contribute to our understanding of their mental health and well-being.

Key Findings

Indigenous LGBTQ young people are diverse with respect to nation/tribe, sexuality, and gender.

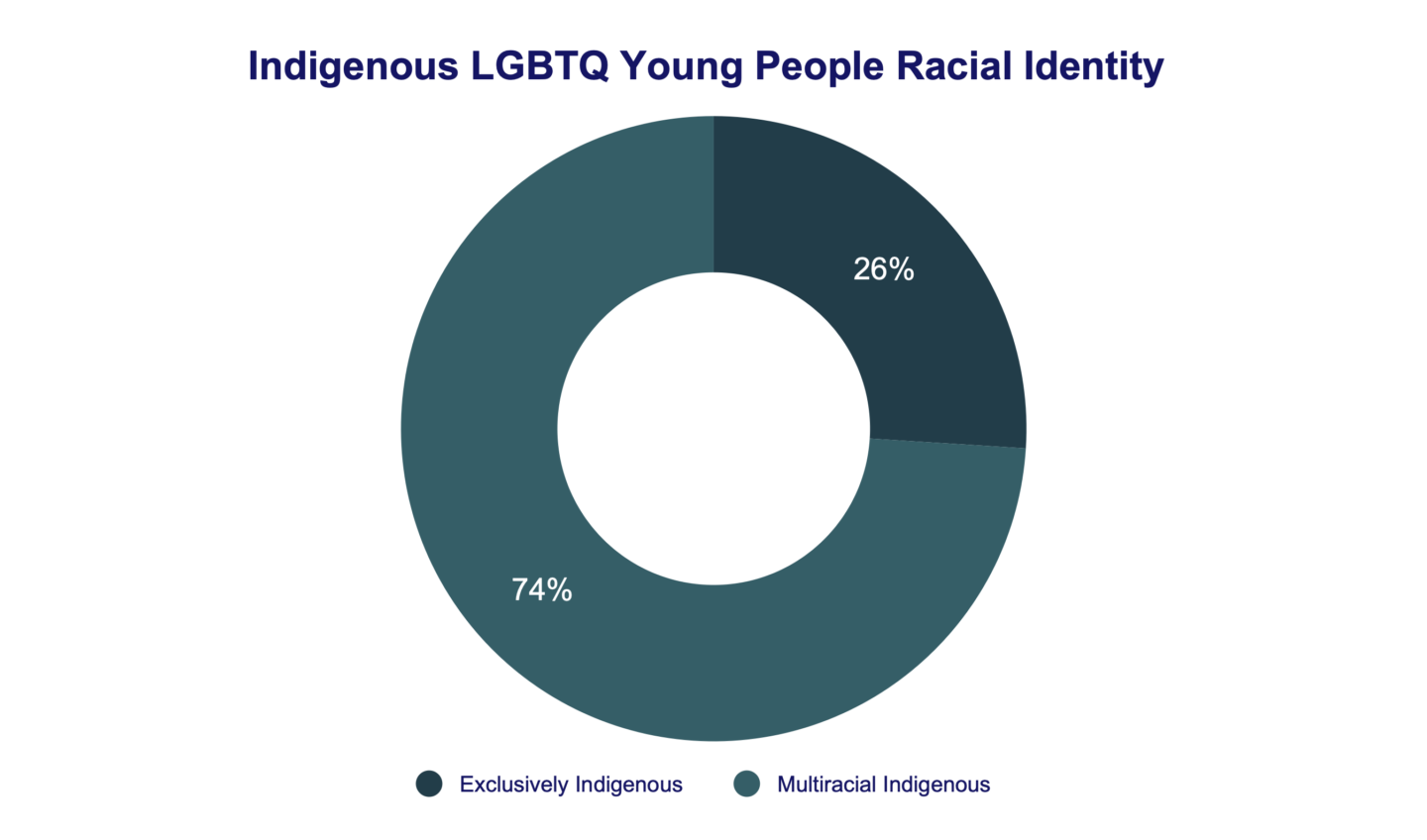

- Of the 1,792 Indigenous LGBTQ young people in our sample, 26% identified as exclusively Indigenous and 74% identified as multiracial Indigenous.

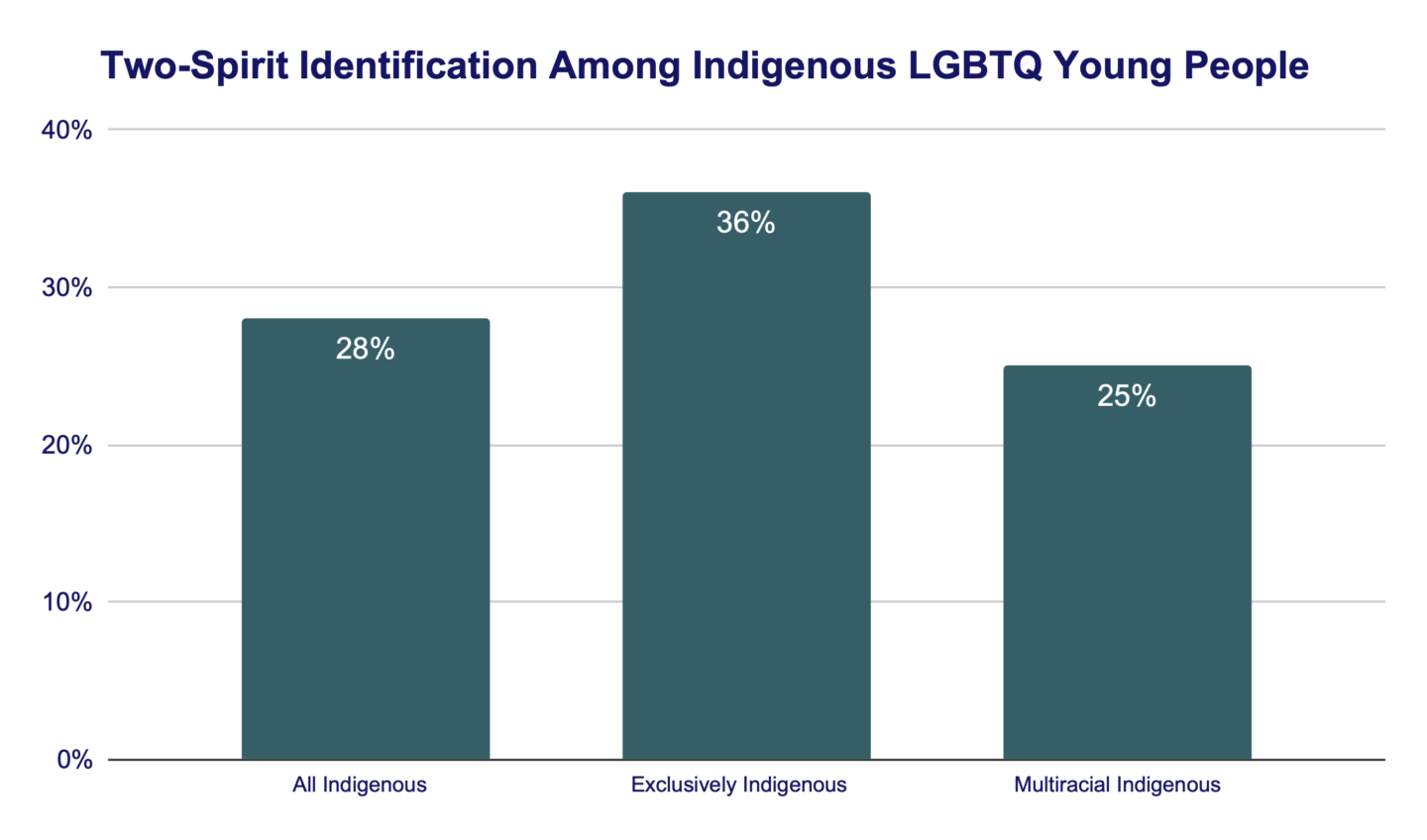

- Just over a quarter (28%) of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported that they identify as Two-Spirit, a term used in many tribal communities to describe those who embody diverse sexualities, genders, gender expressions, and/or gender roles in their community.

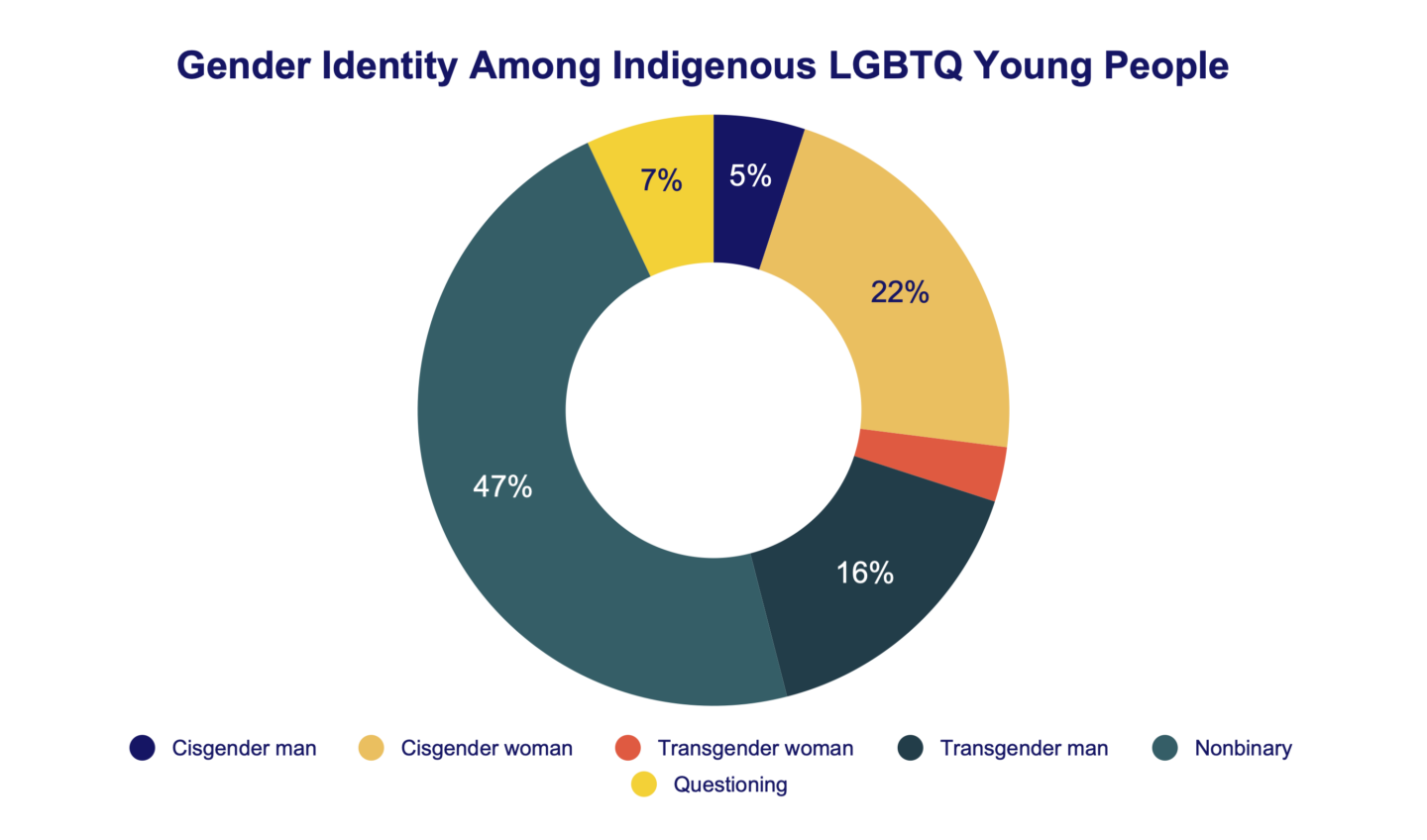

- Two-thirds (66%) of Indigenous LGBTQ young people self-identified as transgender or nonbinary.

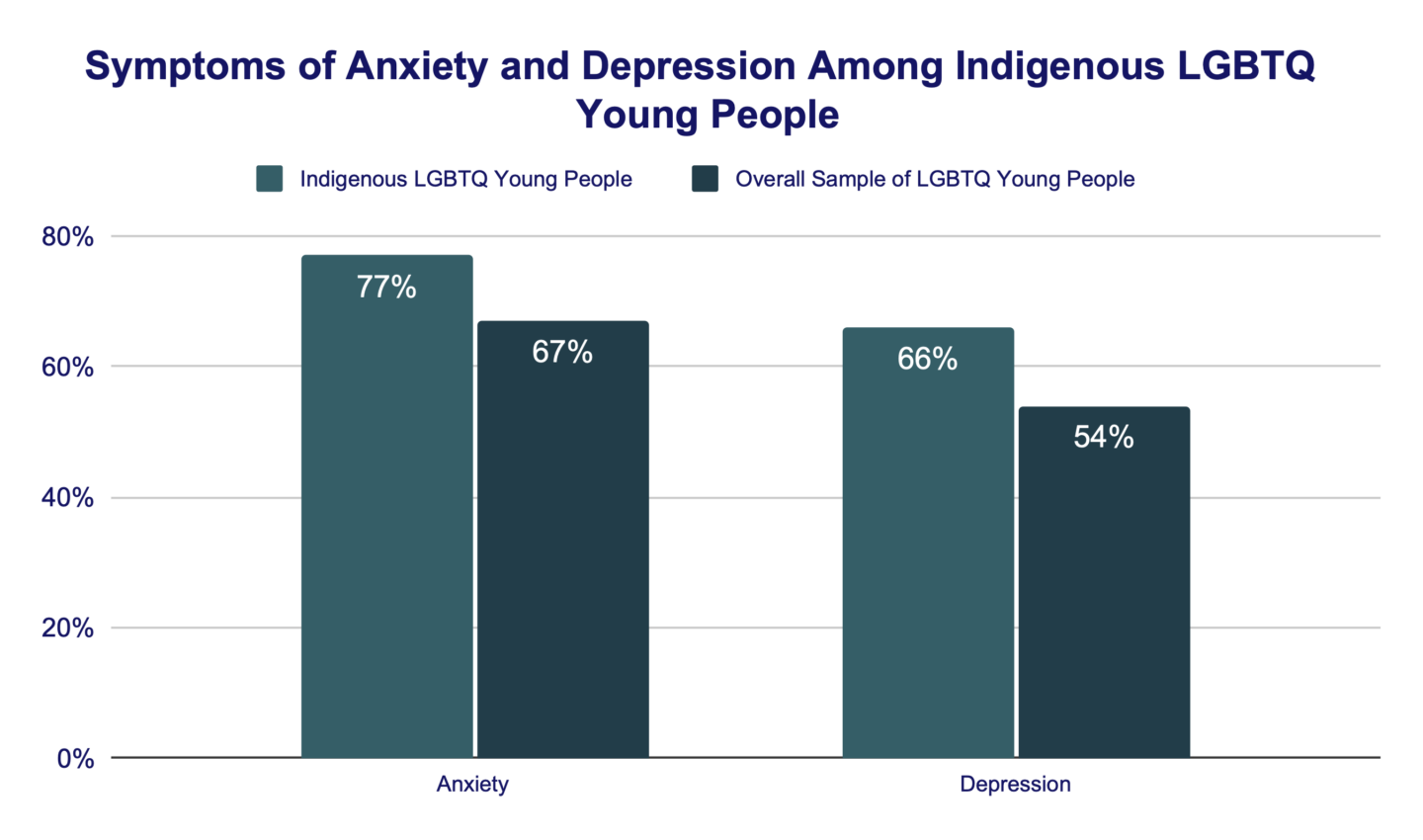

Indigenous LGBTQ young people report higher rates of mental health challenges compared to other LGBTQ young people.

- Over three quarters of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (77%) reported recent symptoms of anxiety and 66% reported recent symptoms of depression.

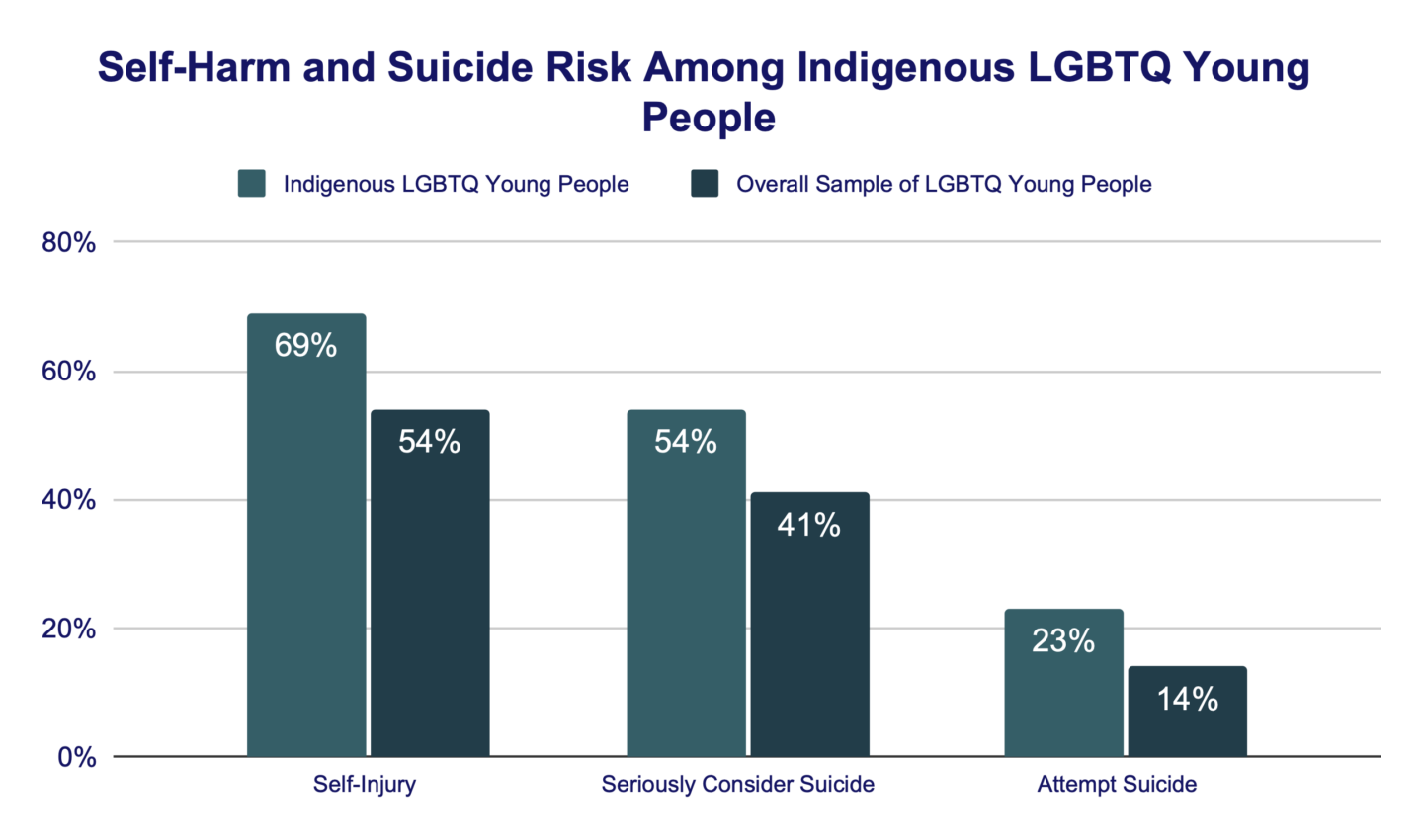

- Over half of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (54%) reported seriously considering suicide in the past year, compared to 41% in the broader sample of LGBTQ young people.

- Nearly a quarter of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (23%) reported attempting suicide in the past year, compared to 14% among the overall sample of LGBTQ young people.

Indigenous LGBTQ young people experience disproportionate structural inequities, as well high rates of anti-LGBTQ stressors.

- Nearly one in ten Indigenous LGBTQ young people (8%) reported having been subjected to conversion therapy, and 70% reported experiencing an attempt to change their LGBTQ identity.

- Over a third of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (34%) reported past or current homelessness, which is more than double the rate of homelessness among their non-Indigenous LGBTQ peers.

- Nearly half of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (48%) reported experiencing food insecurity, compared to just under a third of non-Indigenous LGBTQ young people (30%).

Support from others is an important protective factor for Indigenous LGBTQ young people.

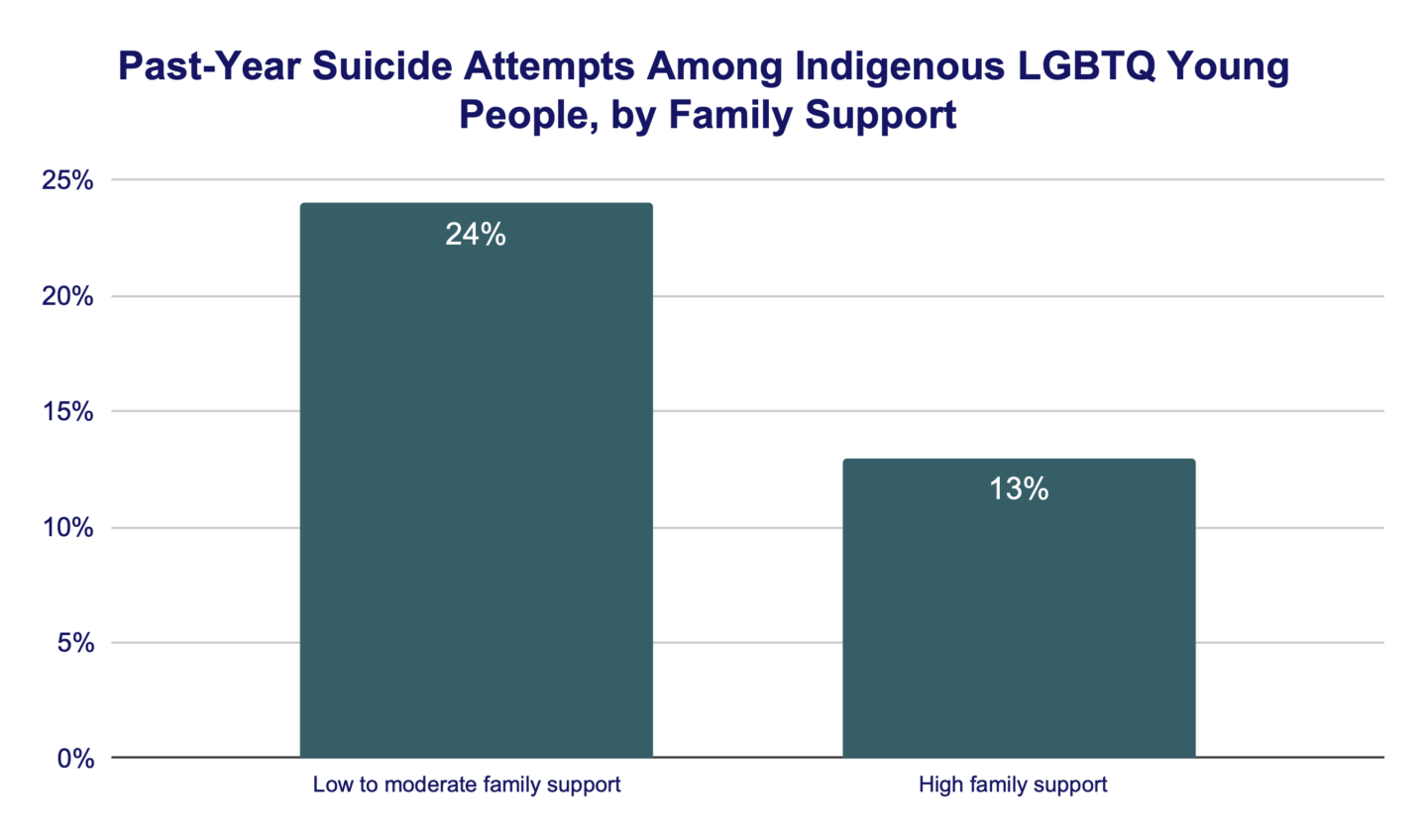

- Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported high levels of support from their families had significantly lower rates of attempting suicide in the past year (13%), compared to their Indigenous LGBTQ peers who reported low levels of family support (24%).

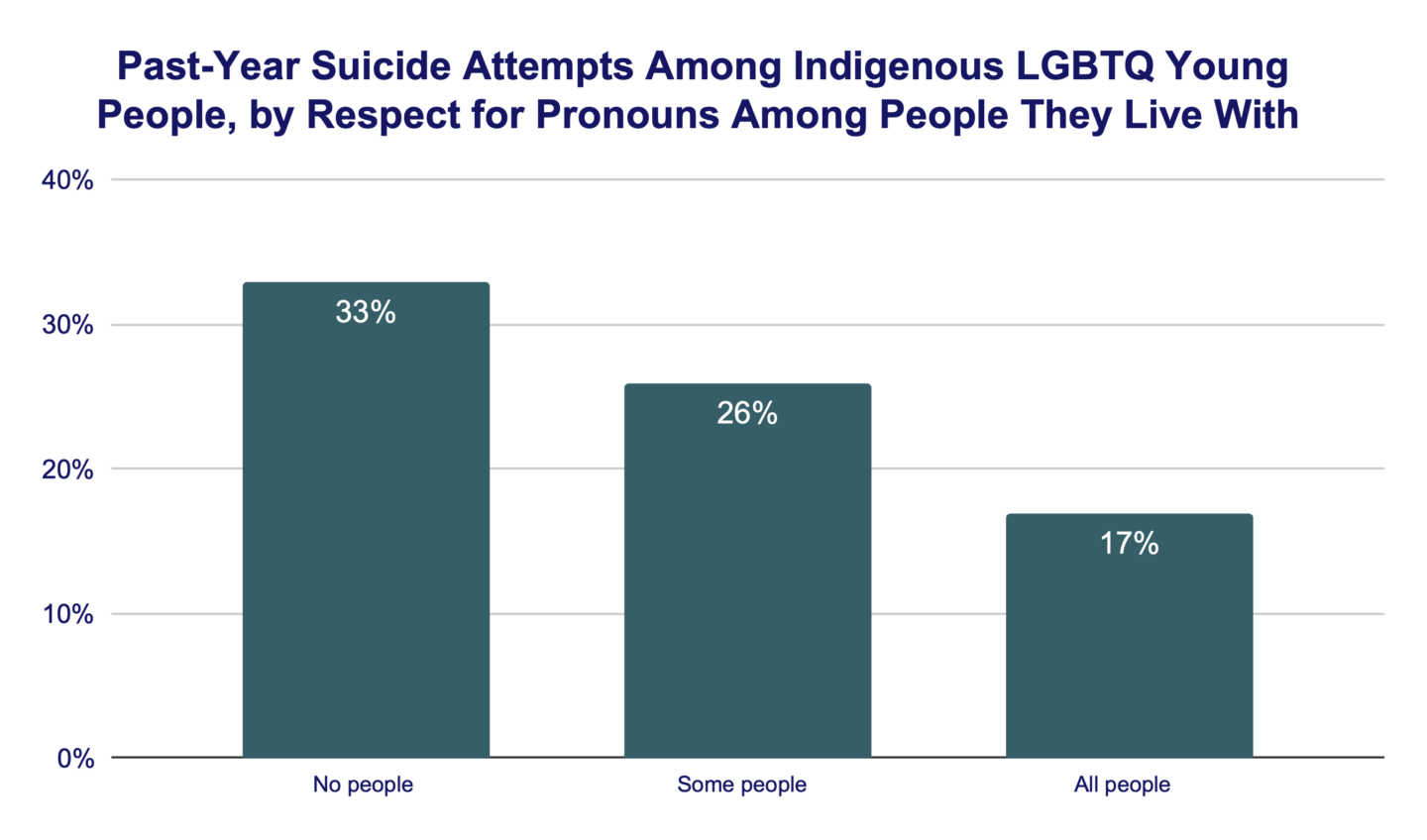

- Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people who reported that all of the people they live with respect their pronouns reported having attempted suicide in the past year at nearly half the rate of those who reported that none of the people they live with respect their pronouns (17% vs. 33%).

Methodology Summary

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data using an online survey platform between September and December 2022. The survey was offered in both English and Spanish. An analytic sample of over 28,000 LGBTQ young people ages 13 to 24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. All participants were asked, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, more than one race or ethnicity, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, Middle Eastern or North African, White/Caucasian, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Young people who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question where they were able to select with which races or ethnicities they identified. The current analyses include the 1,792 LGBTQ young people who either identified as exclusively American Indian/Alaskan Native or as multiracial American Indian/Alaskan Native, henceforth referred to as Indigenous unless otherwise specified.

Recommendations

Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported rates of poor mental health indicators that were much higher than the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Indeed, 23% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people attempted suicide in the past year compared to 14% of the overall sample. These findings not only highlight the hardships that Indigenous LGBTQ young people face due to systemic oppression (e.g., housing instability, foster care, food insecurity), but also due to their LGBTQ identity (e.g., increased rates of discrimination and victimization). This compounding exposure to stressors places Indigenous LGBTQ young people at greater risk for suicide. There is an urgent need to decolonize systems that oppress Indigenous LGBTQ young people. Decolonizing could include cultural competency training for healthcare providers to improve understanding and support, and supporting initiatives that are led by Indigenous communities, ensuring that suicide prevention strategies are culturally relevant and community-specific. Additionally, it is crucial to increase funding to existing community services, such as Native Health Services, specifically for Indigenous suicide intervention and prevention initiatives. Furthermore, given the protectiveness of family support and home environments, individuals in the lives of Indigenous LGBTQ young people, such as family members, community leaders, and other young people, must be involved in the development of suicide prevention strategies.

Note: Decolonization has several meanings but here we are using it to mean a process of opposing or removing traditional colonial ways of thinking and acting and instead centering Indigenous peoples, knowledge, and values (Sium et al., 2012)

BACKGROUND

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people report disproportionately poor mental health compared to their straight and cisgender peers. More specifically, LGBTQ young people report higher rates of anxiety, depression, self-harm, seriously considering suicide, and attempting suicide compared to straight, cisgender young people (Gaylor, et al., 2023; Johns et al., 2020). These mental health symptoms are not inherent to being LGBTQ. Rather, they arise from the minority stress associated with the societal challenges that come with holding a marginalized identity (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003). LGBTQ young people often confront additional stressors beyond those of their peers, including family or caregiver rejection, discrimination, and violence (Kosciw et al., 2020). Such negative experiences can lead to the internalization of homophobic, biphobic (Baams et al., 2015), and transphobic (Pellicane & Ciesla, 2021) attitudes, feelings of burdensomeness, and deteriorating mental health (Green, Price, & Dorison, 2022). It is important to note, however, that the experiences within the LGBTQ community are not monolithic; diversity in identities and backgrounds can compound stress and worsen mental health outcomes. For example, transgender and nonbinary young people report poorer mental health than cisgender young people (Johns et al., 2019), even when compared to their cisgender LGBQ peers (Price-Feeney et al., 2020). Bisexual, pansexual, queer, or multisexual young people also report worse mental health challenges than their gay or lesbian peers (Price et al., 2021). Furthermore, intersectional differences within LGBTQ young people of different racial and ethnic identities have been observed among young people who are both Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) and LGBTQ (Price et al., 2022), Latinx and LGBTQ (Price et al., 2023), Black and LGBTQ (Price et al., 2020), or Multiracial and LGBTQ (Price et al., 2022).

The history of Indigenous peoples in what is now known as North America has been significantly shaped by the effects of European colonization and expansion, resulting in profound changes to their traditional ways of life. Exposure to unfamiliar diseases and advanced military technologies had catastrophic effects for Indigenous individuals, families, and communities (Woolford et al., 2014). The effects of this violence and deprivation can still be observed among contemporary Indigenous communities. A robust body of research on historical trauma among Indigenous communities has found that loss of historic lands and cultural traditions is associated with poorer physical and mental health among Indigenous individuals (Fast & Collin-Vezina, 2020). In addition, Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and cultural communities and placed in residential boarding schools where they were forced to assimilate to the Christian faith and dominant White culture. This forced assimilation has been documented to have detrimental effects on the health of residential school survivors and their descendants (Fast & Collin-Vezina, 2020). Colonization impacted various aspects of Indigenous identity, including those who identified with non-traditional gender roles and sexualities, historically recognized within many tribes as Two-Spirit—a term that acknowledges the unique cultural context of these individuals (Pruden, 2019). The term Two-Spirit originated in 1990 at the Third Annual Intertribal Native American/First Nations Gay And Lesbian Conference to describe those who embody diverse sexualities, genders, gender expressions, and/or gender roles in their community (Pruden, 2019; Pruden, 2020). Pre-colonization societies often held Two-Spirit people in high esteem (Jacobs, 1997), but the arrival of White settlers and the Christian Church disrupted this acceptance, leading to significant social challenges that continue to affect these communities today (Robinson, 2022).

The legacies of dispossession and violence are evident in the contemporary challenges faced by Indigenous individuals and communities. Today, there are approximately 9.7 million Indigenous people living in the U.S. (Jones et al., 2022). Indigenous individuals experience disproportionately high rates of homelessness, poverty, and lack of access to education or employment services (Sarche & Spacer, 2008). Violence is a significant problem for many Indigenous Americans. The Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women (MMIW) campaign has done important work in recent years to raise awareness of the high rates of violence experienced by Indigenous women in North America and the lack of attention paid by law enforcement to these crimes (Joseph, 2021). Anti-Native racism and discrimination are also pervasive challenges. Indigenous people report high rates of discrimination in the domains of health care, employment, and interactions with law enforcement (Findling et al., 2019). It is well-documented that suicide rates are alarmingly high among Indigenous young people. Nearly 20% of Indigenous American students have contemplated suicide and almost one in six reported a suicide attempt in the last year (Schuler et al., 2023).

These structural challenges and consequentially, accumulated stress, often result in poor mental health among Indigenous individuals, particularly those who are LGBTQ. LGBTQ Indigenous people also report higher rates of anxiety and depression compared to their non-LGBTQ Indigenous peers (Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto, 2018). Bisexual Indigenous students report the highest rates of suicide attempts, followed by their gay and lesbian peers, all of whom report higher rates than their heterosexual peers (Schuler et al., 2023). LGBTQ Indigenous people are more likely to report having suicidal thoughts if they are a survivor of residential boarding school or raised by a survivor of a residential boarding school (Evans-Campbell et al., 2012). LGBTQ Indigenous people report higher rates of violence than their non-LGBTQ Indigenous peers, including higher rates of physical assault, sexual assault, childhood trauma, and intimate partner violence (Balsam et al., 2004; Lehavot et al., 2010). Violence can have tangible impacts on mental health, with LGBTQ Indigenous individuals who have been violently victimized reporting higher rates of anxiety than their peers who have not endured such trauma (Walters, 2010). Indigenous LGBTQ people also experience anti-LGBTQ bias and discrimination. Transgender Indigenous individuals report high rates of experiencing transphobia and racial discrimination (Marcellin et al., 2014). LGBTQ Indigenous people also report high rates of unemployment and low household incomes (Walters, 2010), which can make it challenging to access mental health care.

Suicide prevention efforts in many tribal and urban Indigenous communities have highlighted the need for culturally specific mental health interventions. The combined effects of both anti-LGBTQ discrimination and racial discrimination can make it challenging for Indigenous LGBTQ people to access mainstream mental health services (Ferlatte et al., 2019). Some LGBTQ Indigenous people report that anti-LGBTQ biases in tribal communities make it harder for them to access cultural support and services (Alaers, 2011; Walters et al. 2006). However, many tribal communities are returning to their historical acceptance of Two-Spirit tribal members, with LGBTQ Indigenous people reporting very high rates of cultural belonging and cultural pride (Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto, 2018). Engagement with one’s traditional culture is associated with better mental health outcomes among LGBTQ Indigenous people (Fieland et al. 2007). One study among Two-Spirit Indigenous men found that the practice of smudging – or ritual cleansing – is associated with lower suicidality (Ferlatte et al., 2019). Annual gatherings of Two-Spirit Indigenous people have also been found to provide collective healing from trauma (Meyer-Cook & Labelle, 2004; Taylor & Peter, 2011). Learning more about one’s traditional culture and building community with other LGBTQ Indigenous people may be effective interventions for decreasing suicide risk among LGBTQ Indigenous young people (Robinson, 2022; Sylilboy et al., 2022).

While there is a growing body of literature on mental health and suicide risk among LGBTQ Indigenous young people, much of this work relies on small samples. One notable exception is a report produced in 2020 by GLSEN and the Center for Native American Youth, which examined experiences of Indigenous LGBTQ young people in schools (Zongrone et al., 2020). Using a national U.S. sample of nearly 1,800 Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 24 who participated in our 2023 National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People, this report examines the mental health and well-being of Indigenous LGBTQ young people.

METHODOLOGY

A quantitative cross-sectional design was used to collect data using an online survey platform between September and December 2022. The survey was offered in both English and Spanish. An analytic sample of over 28,000 LGBTQ young people ages 13 to 24 who resided in the United States was recruited via targeted ads on social media. All participants were asked, “What best describes your race or ethnicity?” with options: Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino/Latinx, more than one race or ethnicity, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, Middle Eastern or North African, White/Caucasian, and another race or ethnicity (please specify). Young people who selected more than one race or ethnicity were asked a follow-up question where they were able to select with which races or ethnicities they identified. The current analyses include the 1,792 LGBTQ young people who either identified as exclusively American Indian/Alaskan Native or who identified as multiracial American Indian/Alaskan Native, henceforth just referred to as Indigenous unless otherwise specified. Please note that young people who identified exclusively as Native Hawaiians and not American Indian/Alaskan Native were not included in these analyses but were included in our previous report: The Mental Health and Well-Being of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) LGBTQ Youth. Young people who indicated a Indigenous identity were asked to provide the name of their nation/tribe and whether they are Two-Spirit (Canadian Institutes for Health Research Institute of Gender and Health, 2020).

The overall survey included a maximum of 150 questions, including questions on considering and attempting suicide in the past 12 months taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020) and measures of anxiety and depression based on the GAD-2 and PHQ-2, respectively (Plummer et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2010). Each analysis was run separately for Indigenous young people who identified as exclusively Indigenous compared to those who were multiracial Indigenous and another race/ethnicity. Logistic regression models were used to predict attempting suicide in the past year, adjusting for sex assigned at birth, age, gender identity, and sexual orientation. All reported comparisons and adjusted odds ratios are statistically significant at least at p<0.05. This means that there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance.

RESULTS

Diversity of Indigenous LGBTQ Young People

Race, Ethnicity, Tribal Affiliation, and Language

Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported a diverse range of cultural, tribal, and linguistic identities. Of the 1,792 Indigenous LGBTQ young people in our sample, 457 (26%) identified as exclusively Indigenous and 1,335 (74%) identified as multiracial, which included Indigenous heritage. Other races and ethnicities reported by multiracial Indigenous LGBTQ young people included White (82%), Latinx (40%), Black (20%), Asian American (10%), Middle Eastern or North African (4%), and Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (4%).

Just over 60% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people in our sample provided their tribal affiliation(s). The most commonly cited tribal affiliations were Cherokee (12%), Choctaw (2%), Navajo (2%), and Ojibwe (1%). Most Indigenous LGBTQ young people (96%) reported that English is the language most spoken in their home. A much smaller portion, just under 2%, reported Spanish as their main language at home, while 0.4% reported that their family uses American Sign Language (ASL), and 1% reported another language such as Navajo, Apache, and Patois.

LGBTQ Identities

Just over a quarter (28%) of Indigenous LGBTQ young people identified as Two-Spirit. LGBTQ young people who were exclusively Indigenous reported higher rates of identifying as Two-Spirit (36%), compared to their LGBTQ peers who were multiracial Indigenous (25%).

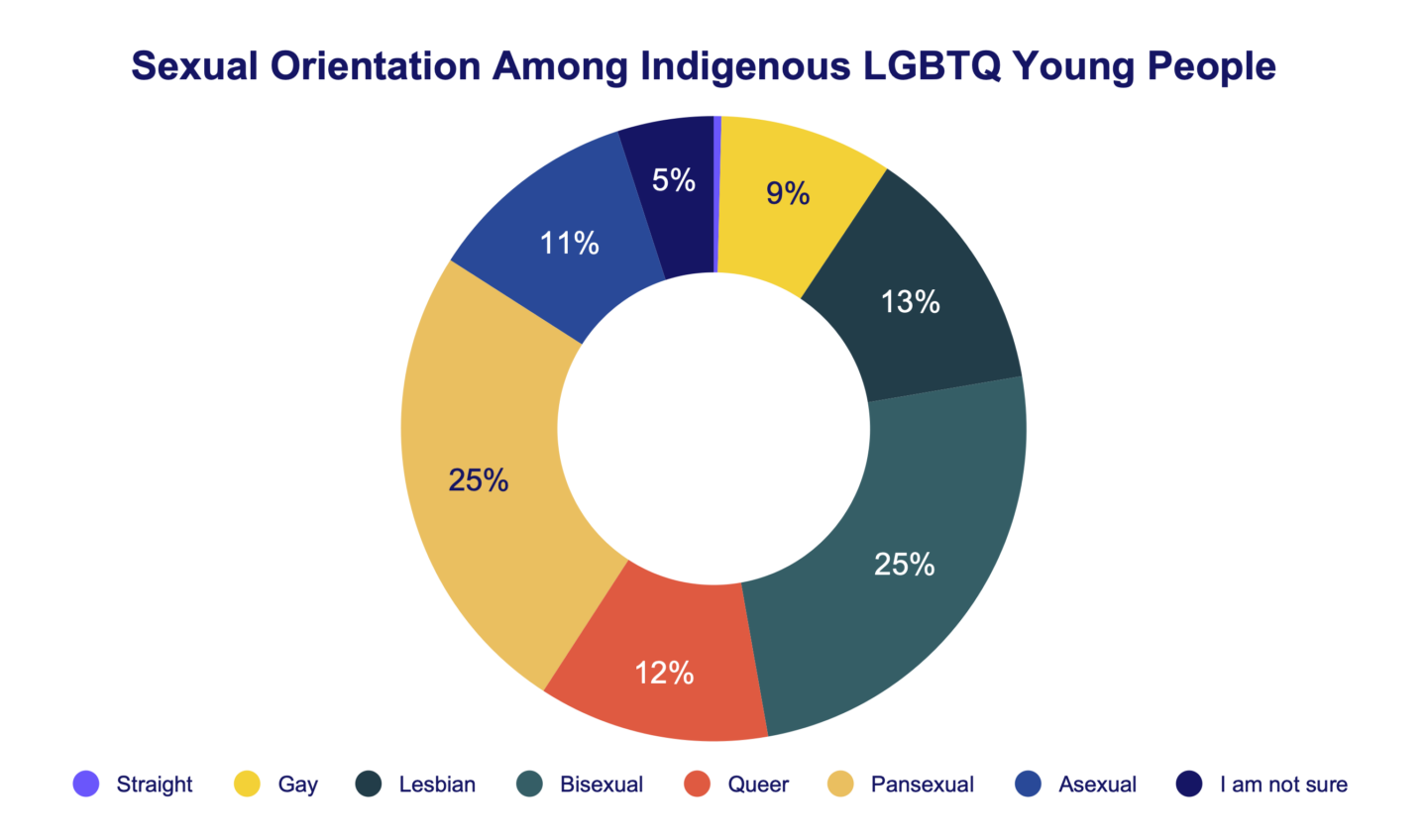

In terms of sexual orientation, bisexual and pansexual were the most frequently endorsed sexual orientations among Indigenous LGBTQ young people, with 25% identifying with each of these orientations, followed by lesbian (13%), queer (12%), asexual (11%), gay (9%), questioning (5%), and straight (0.4%). These rates are similar to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people.

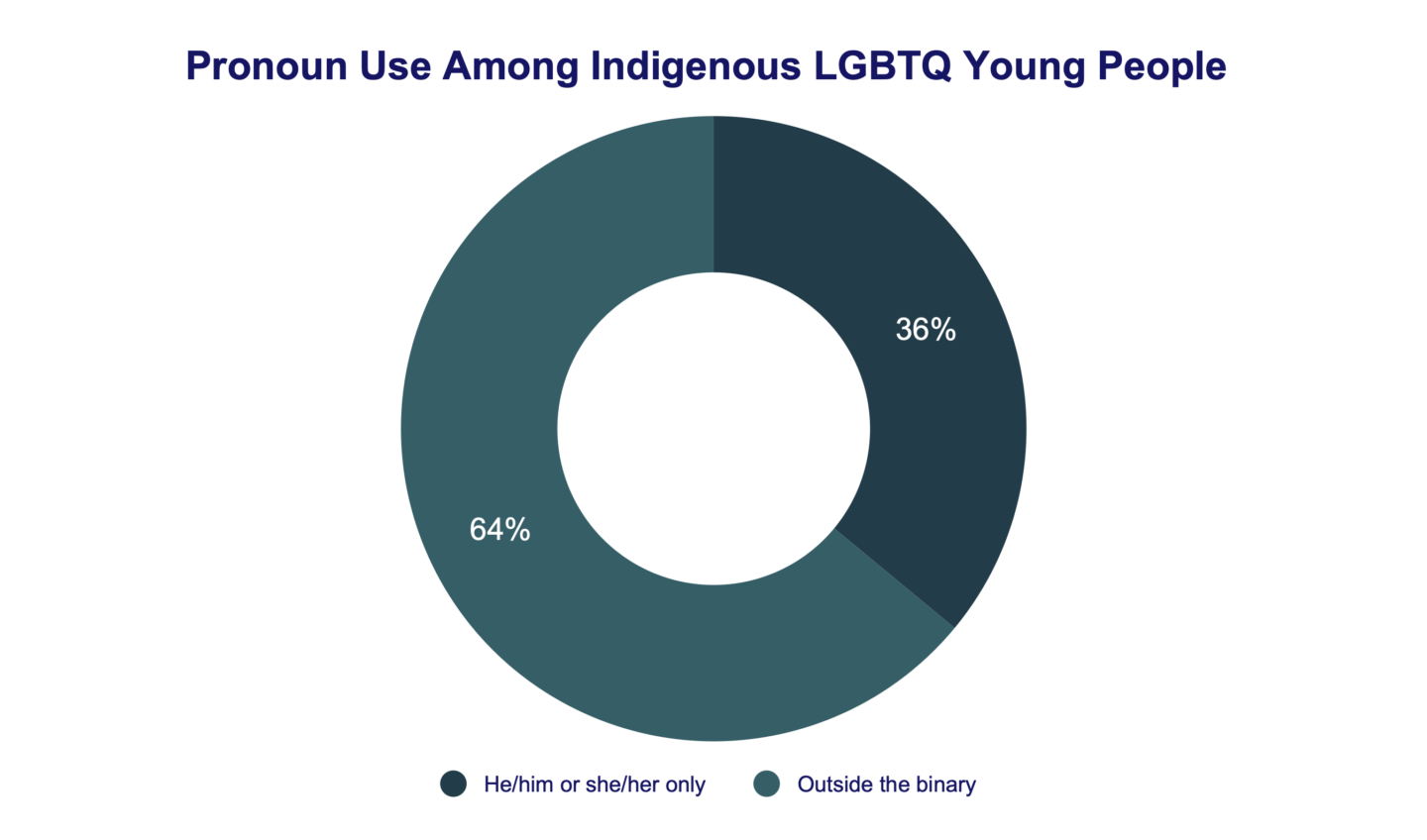

Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of gender diversity compared to their LGBTQ peers of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. For example, 66% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people are transgender or nonbinary compared to 51% in the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. Nearly half of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (47%) identified as nonbinary, 22% as cisgender women or girls, 16% transgender men or boys, 7% were questioning their gender identity, 5% as cisgender men or boys, and 3% as transgender women or girls. Additionally, Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of using pronouns outside of the traditional gender binary (64%) compared to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people (51%). Among them, 13% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported exclusively using they/them pronouns, while 22% reported using them/them in conjunction with he/him or she/her. Finally, more Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported that they identify as a person with a disability (44%), compared to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people (29%).

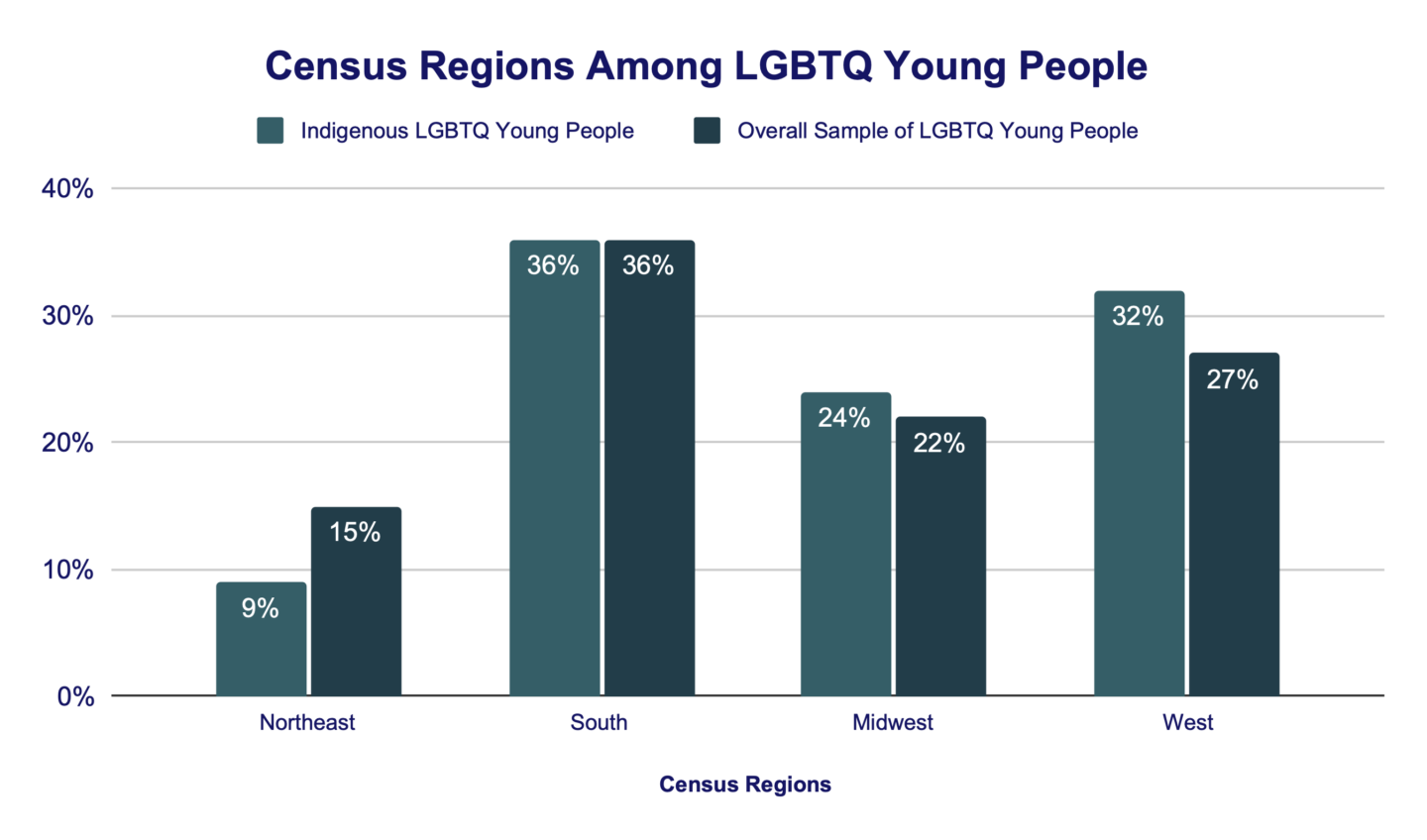

Environmental Demographics

Over a third of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (36%) reported living in the South, followed by 32% in the West, 24% in the Midwest, and 9% in the Northeast. A third (34%) reported that their household only just met their basic economic needs or less, compared to 21% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Additionally, 73% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people were currently enrolled in school. Of those enrolled, 61% were in high school, 19% in middle school, 8% at a four-year university, and 6% at a community or junior college. The majority of these students attended public schools (87%), while 7% were homeschooled, 4% attended private non-religious schools, and 3% attended private religious schools.

Fewer Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported having been born outside the U.S. (3%) compared to the entire sample of LGBTQ young people (7%). Indigenous LGBTQ young people also reported lower rates of having a parent or caregiver born outside of the U.S., although different rates were observed among LGBTQ young people who were exclusively Indigenous (7%) and multiracial Indigenous (19%). Both groups reported lower rates of having a parent or caregiver born outside of the U.S. compared to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people (27%).

Religion and Spirituality

Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported that their religion or spirituality was important or very important to them at significantly higher rates than their non-Indigenous LGBTQ peers. While one in five non-Indigenous LGBTQ young people (21%) reported that their religion or spirituality was important or very important to them, 37% of exclusively Indigenous LGBTQ young people and 32% of multiracial Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported that their religion or spirituality was important or very important to them.

Mental Health and Well-Being

Anxiety and Depression

Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of anxiety and depression than the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. Specifically, 77% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported recent symptoms of anxiety compared to 67% among the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 18 to 24 reported significantly higher rates of recent anxiety (79%) than those aged 13 to 17 (74%). Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people also reported significantly higher rates of recent anxiety (81%) than their Indigenous cisgender LGBQ peers (69%). No significant differences were found in recent anxiety rates between exclusively Indigenous LGBTQ youth and multiracial Indigenous LGBTQ youth.

Furthermore, almost two-thirds of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (66%) reported recent symptoms of depression, which is higher than the rate of recent depression measured in the broader sample of LGBTQ young people (54%). Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 reported significantly higher rates of recent depression (68%) than their peers aged 18 to 24 (61%). Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people also reported significantly higher rates of recent depression (70%) than their Indigenous cisgender LGBQ peers (53%). No significant differences were observed between LGBTQ young people who were exclusively Indigenous and those who were multiracial Indigenous.

Self-Harm and Suicide Risk

Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of self-harm and suicide risk compared to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. The findings had similar demographic differences as those for anxiety and depression, with Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 and those who are transgender and nonbinary reporting higher rates of self-harm and suicide risk .

Overall, more than two thirds of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (69%) reported engaging in self-harm in the past year, compared to 54% of the broader LGBTQ youth sample. Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 reported significantly higher rates of self-harm in the past year (75%) than their peers aged 18 to 24 (58%). Furthermore, Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people reported significantly higher rates of self-harm in the past year (54%) than their Indigenous cisgender LGBQ peers (75%). No significant differences in rates of self-harm were observed between LGBTQ young people identifying as exclusively Indigenous and those who identified as multiracial Indigenous.

Over half of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (54%) reported seriously considering suicide in the past year. This was higher than the rate in the overall sample of LGBTQ young people (41%). Among age groups, Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 reported significantly higher rates of seriously considering suicide in the past year (59%) than their peers aged 18 to 24 (46%). Similarly, Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people reported significantly higher rates of seriously considering suicide in the past year (58%) than their cisgender LGBQ peers (43%). No significant differences in rates of seriously considering suicide were observed between LGBTQ young people who exclusively identified as Indigenous and those identifying as multiracial Indigenous.

Nearly a quarter of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (23%) reported attempting suicide in the past year, compared to 14% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 reported significantly higher rates of suicide attempts in the past year (27%) compared to Indigenous LGBTQ their peers aged 18 to 24 (15%). Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people also reported significantly higher rates of suicide attempts in the past year (27%) than their Indigenous cisgender LGBQ peers (13%). No significant differences in rates of attempting suicide were observed between LGBTQ young people who exclusively identified as Indigenous and those who identified as multiracial Indigenous. Controlling for sex assigned at birth, age, gender identity, and sexual orientation, Indigenous LGBTQ young people had 66% higher odds of attempting suicide in the past year compared to LBGTQ young people who were not Indigenous (aOR =1.66, 95% CI [1.44, 1.90], p<0.001).

Risk Factors for Suicide Among Indigenous LGBTQ Young People

Access to Mental Health Care

Access to Care

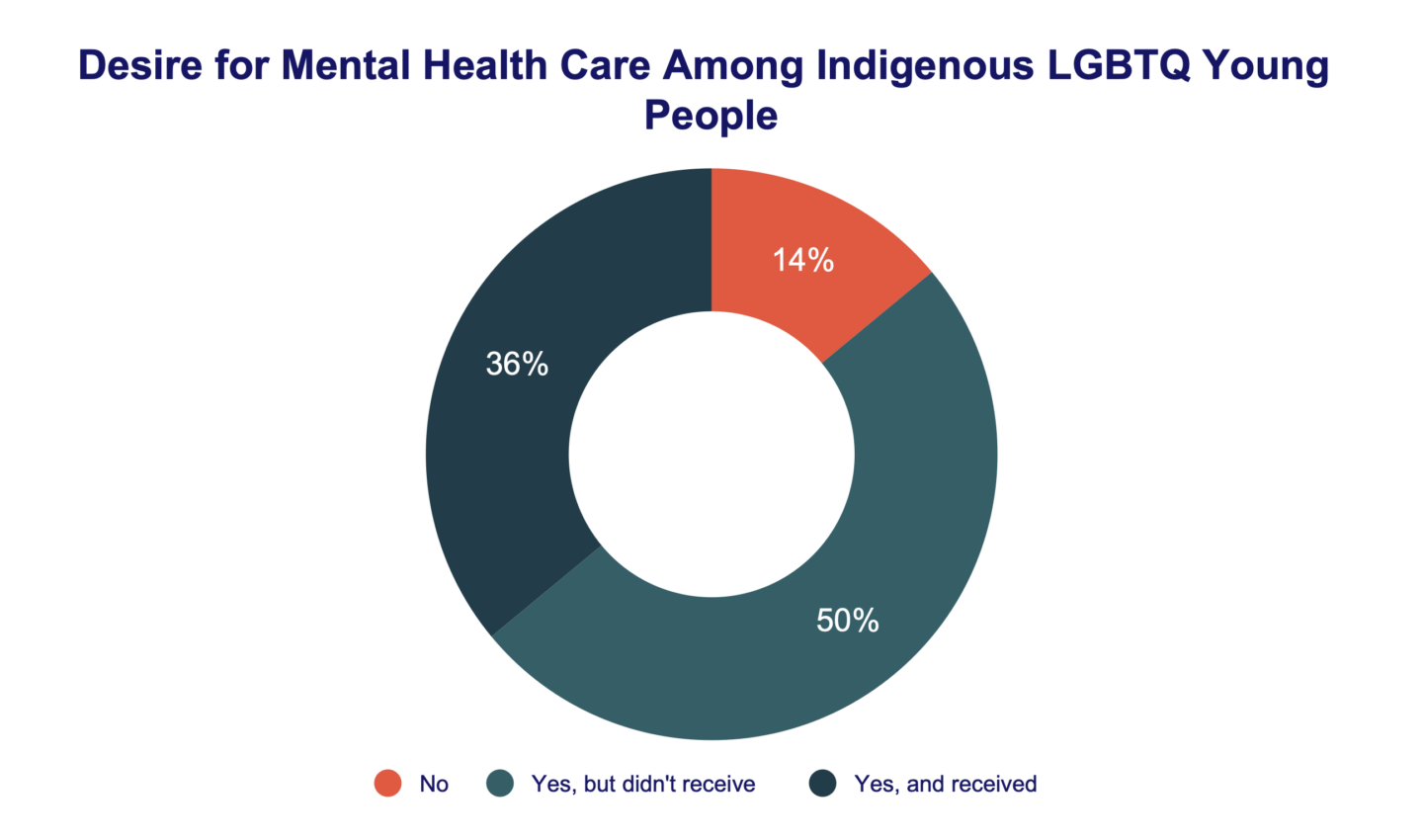

Despite reporting disproportionately high rates of mental health symptoms and suicide risk, Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported a number of barriers to accessing mental health care. A substantial majority of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (86%) reported that they wanted psychological or emotional counseling from a counselor or mental health professional in the past year, and 14% reported that they did not want any mental health care in the past year. Among Indigenous LGBTQ young people who did want mental health care, 36% reported that they did not receive it. Rates of not receiving desired mental health care were higher among Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 (62%) than their peers aged 18 to 24 (52%).

Barriers to Care

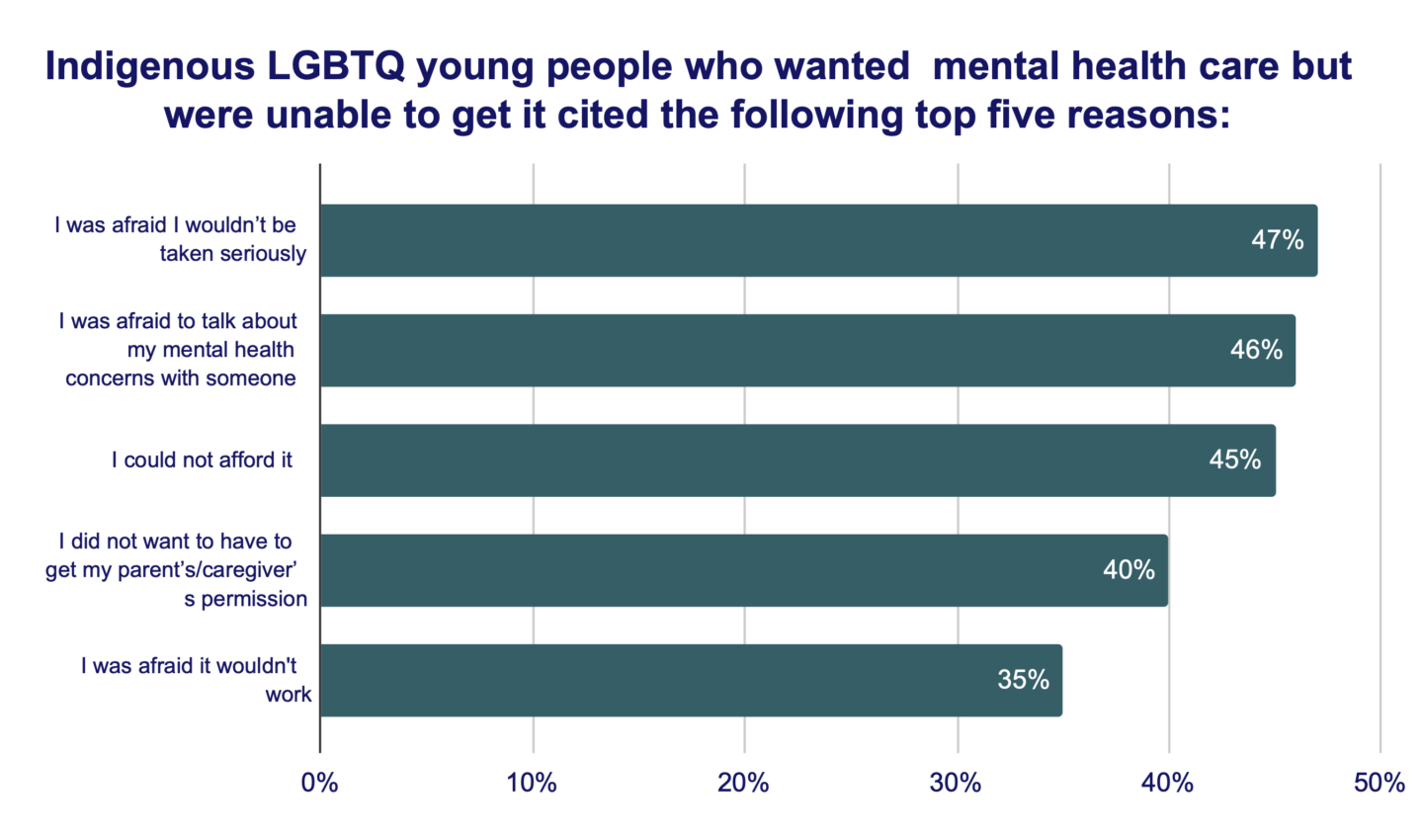

When asked about barriers to receiving mental health care, 47% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported concerns about not being taken seriously, 46% were afraid to discuss their mental health concerns with someone else, 45% cited financial constraints, 40% did not want to have to receive a parent’s/caregiver’s permission, and 35% were afraid mental health care would not work. These were also the top five barriers to access to mental health care for the broader sample of LGBTQ young people; however, notably, Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of economic barriers.

Conversion Therapy and Change Attempts

Conversion Therapy

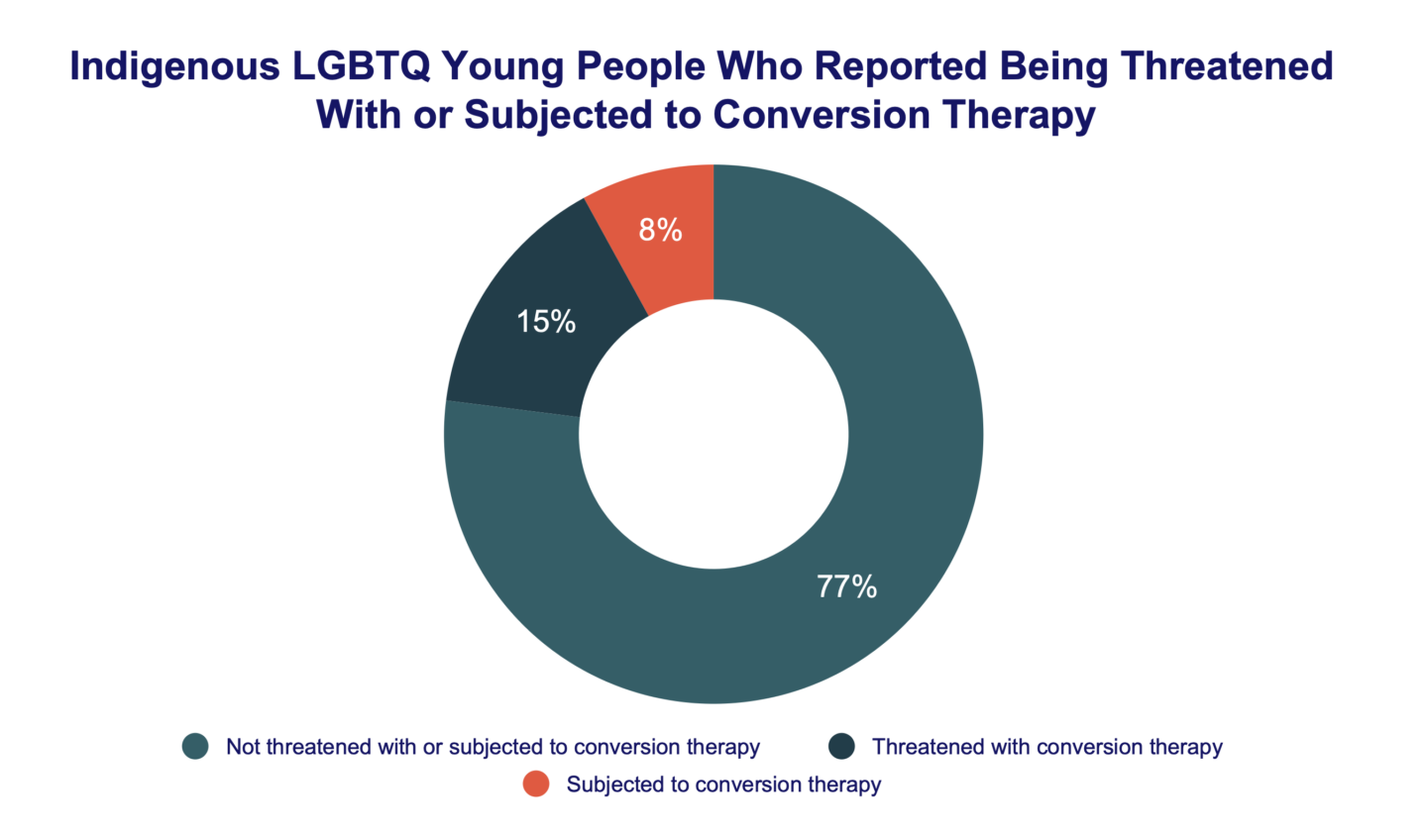

Conversion therapy, defined as attempts by licensed professionals (e.g., psychologists or counselors) or religious leaders to alter sexual attractions and behaviors, gender expression, or gender identity, still occurs regularly in the U.S. despite well-documented evidence of its harm on the health of LGBTQ young people (Forsythe et al., 2022; Green et al., 2020). Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of experiencing conversion therapy than the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. Eight percent of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported having been subjected to conversation therapy, compared to 5% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. An additional 15% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported that they were threatened with conversion therapy (but not subjected to it), compared to 9% of the broader sample of LGBTQ young people.

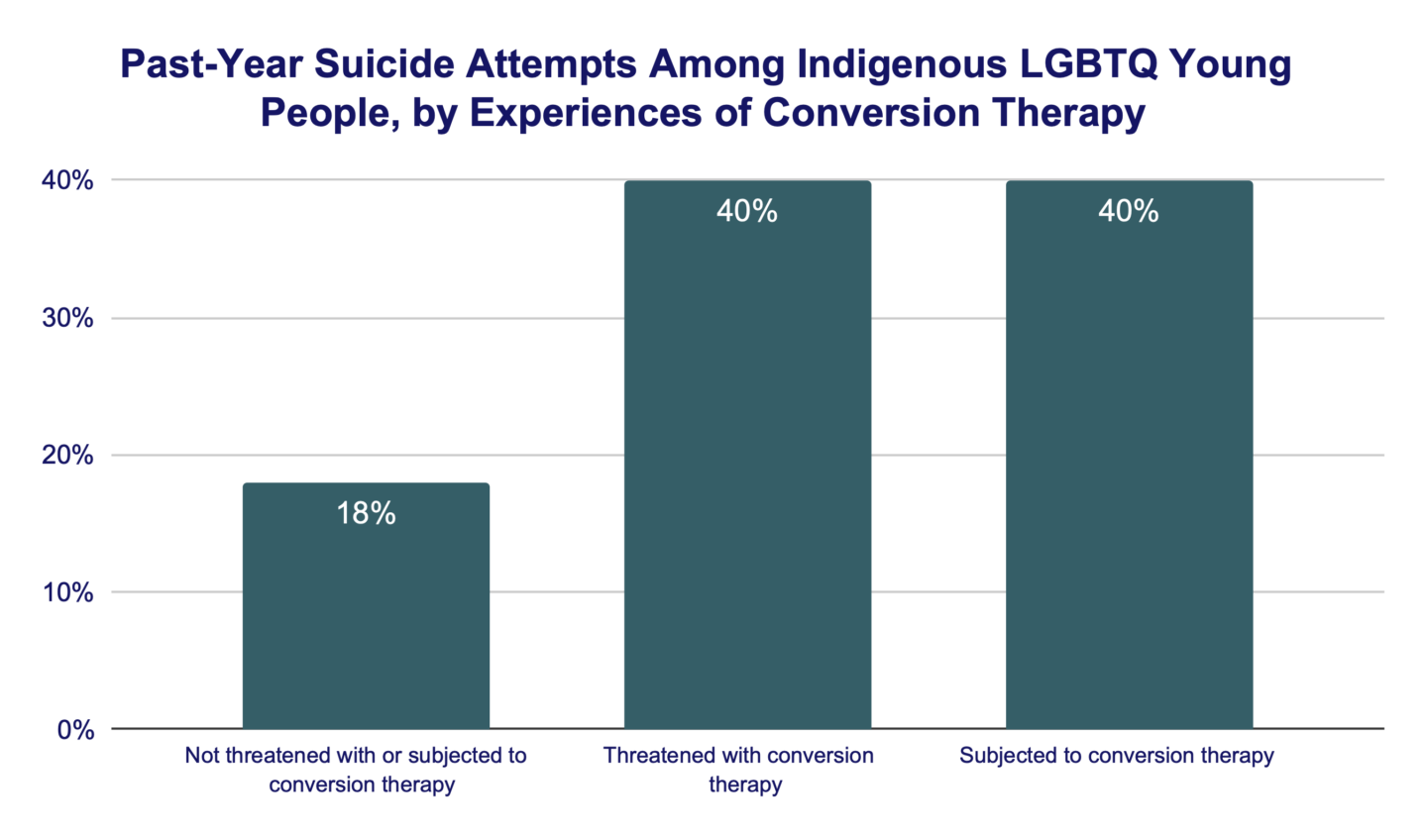

Among Indigenous LGBTQ young people who had undergone conversion therapy, 54% disclosed receiving it from a pastor or priest at their church or house of worship, 50% indicated that a religious leader not affiliated with their church or house of worship administered it, and 34% reported receiving it from a healthcare professional. As of the writing of this report, licensed professionals are banned from engaging in conversion therapy practices in 22 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, making this finding even more alarming. For Indigenous LGBTQ young people, experiencing conversion therapy was associated with more than two times higher odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR=2.29, 95% CI [1.45, 3.60], p<0.001). Furthermore, 40% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported either being subjected to conversion therapy or threatened with it also reported attempting suicide in the past year, compared to 18% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people who had neither been subjected nor threatened with conversion therapy.

Change Attempts

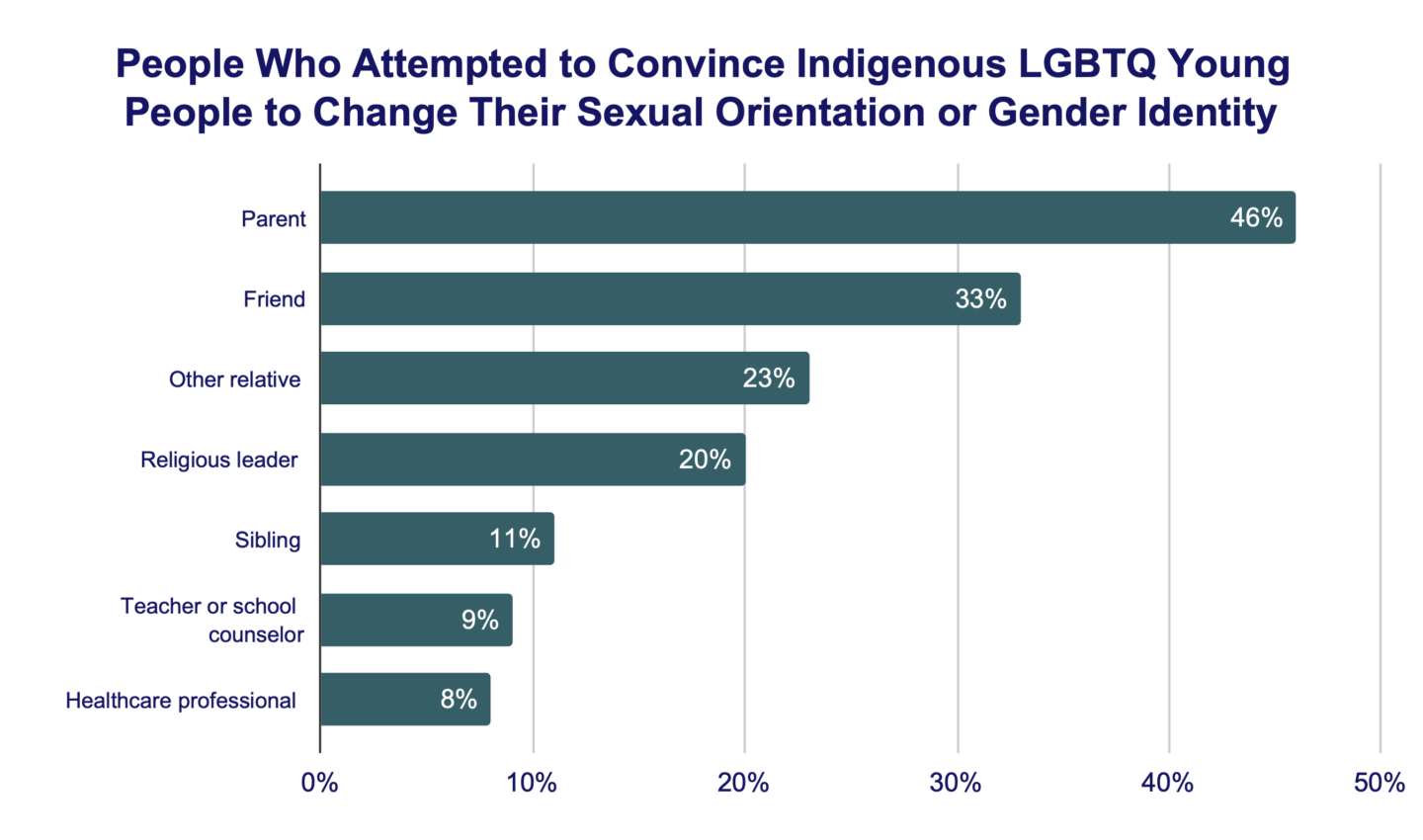

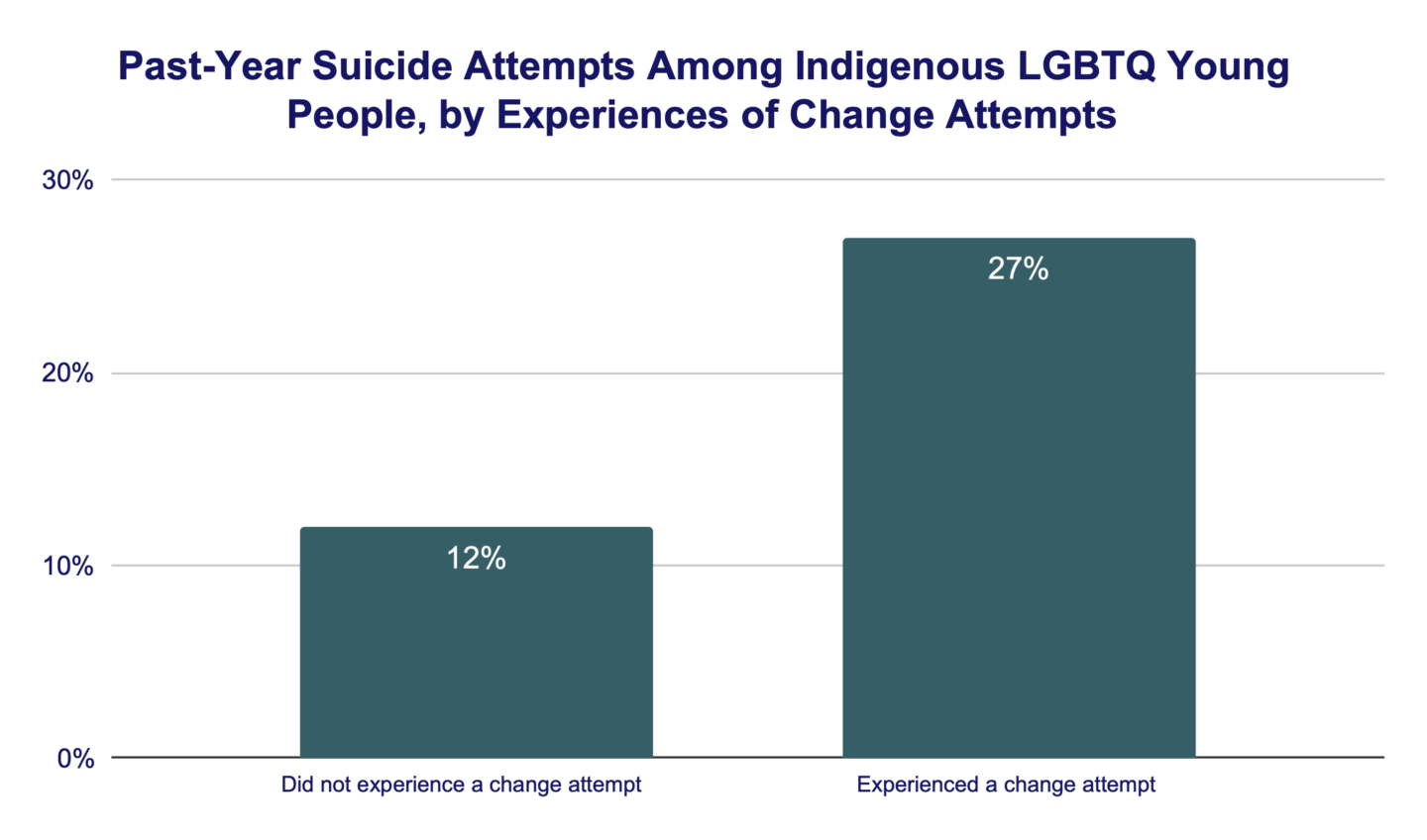

Broader than conversion therapy, “change attempts” encompass informal words or actions aimed at convincing LGBTQ young people to alter their sexual orientation or gender identity. Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of experiencing identity change attempts than the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Over two thirds of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (70%) reported that they had experienced a change attempt, compared to 56% in the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. These change attempts came from a wide variety of individuals in young people’s lives. Nearly half of Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported experiencing a change attempt attributed it to a parent (46%), while 33% reported change attempts from friends, 23% from other relatives, 20% from religious leaders, 11% from a sibling, 9% from a teacher or school counselor, and 8% from a healthcare professional. Change attempts were also associated with higher suicide risk. Over a quarter of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (27%) who reported at least one change attempt in the past year also reported a past-year suicide attempt, compared to just 12% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people who did not experience any change attempts. Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported experiencing a change attempt had nearly two and a half times higher odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR= 2.48, 95% CI [1.72, 3.57], p<0.001).

Structural Inequities

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) has identified five social determinants of health, including economic stability (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion 2020). This stability, encompassing factors such as housing stability and food security, plays a crucial role in the mental health of young people.

Homelessness

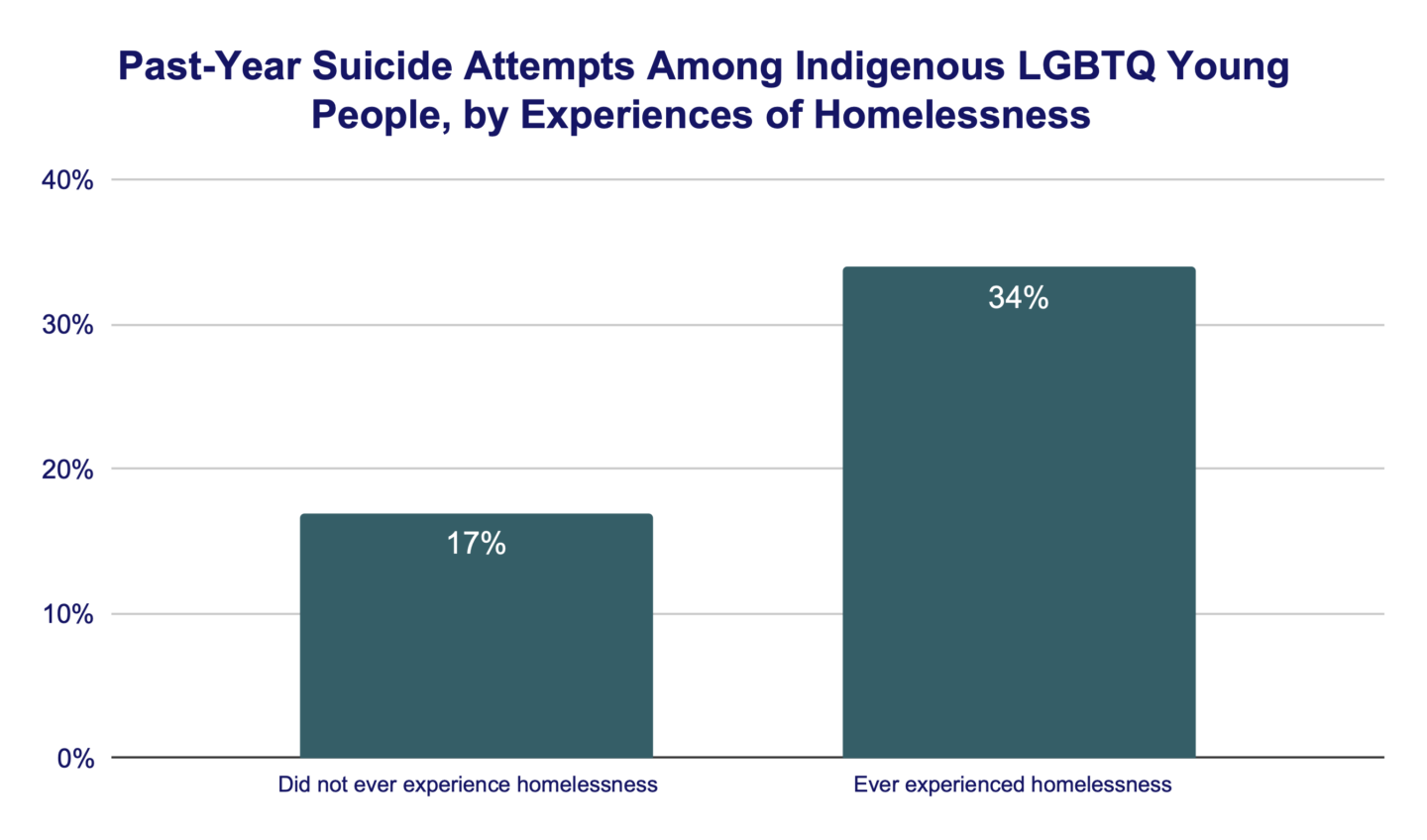

Over a third (34%) of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported being homeless either at the time of the survey or at some point in the past, even if only for a short period of time. This rate is more than double the rate of homelessness among the broader sample of LGBTQ young people (16%). Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people reported higher rates of homelessness than their cisgender LGBQ peers (37% vs. 27%) as did Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 18 to 24 compared to their younger peers aged 13 to 17 (41% vs. 31%). Current or past homelessness was associated with higher rates of suicide risk. Indigenous LGBTQ young people who had a history of homelessness reported past-year suicide attempts at twice the rate of Indigenous LGBTQ peers who did not experience homelessness (34% vs. 17%).

Foster Care

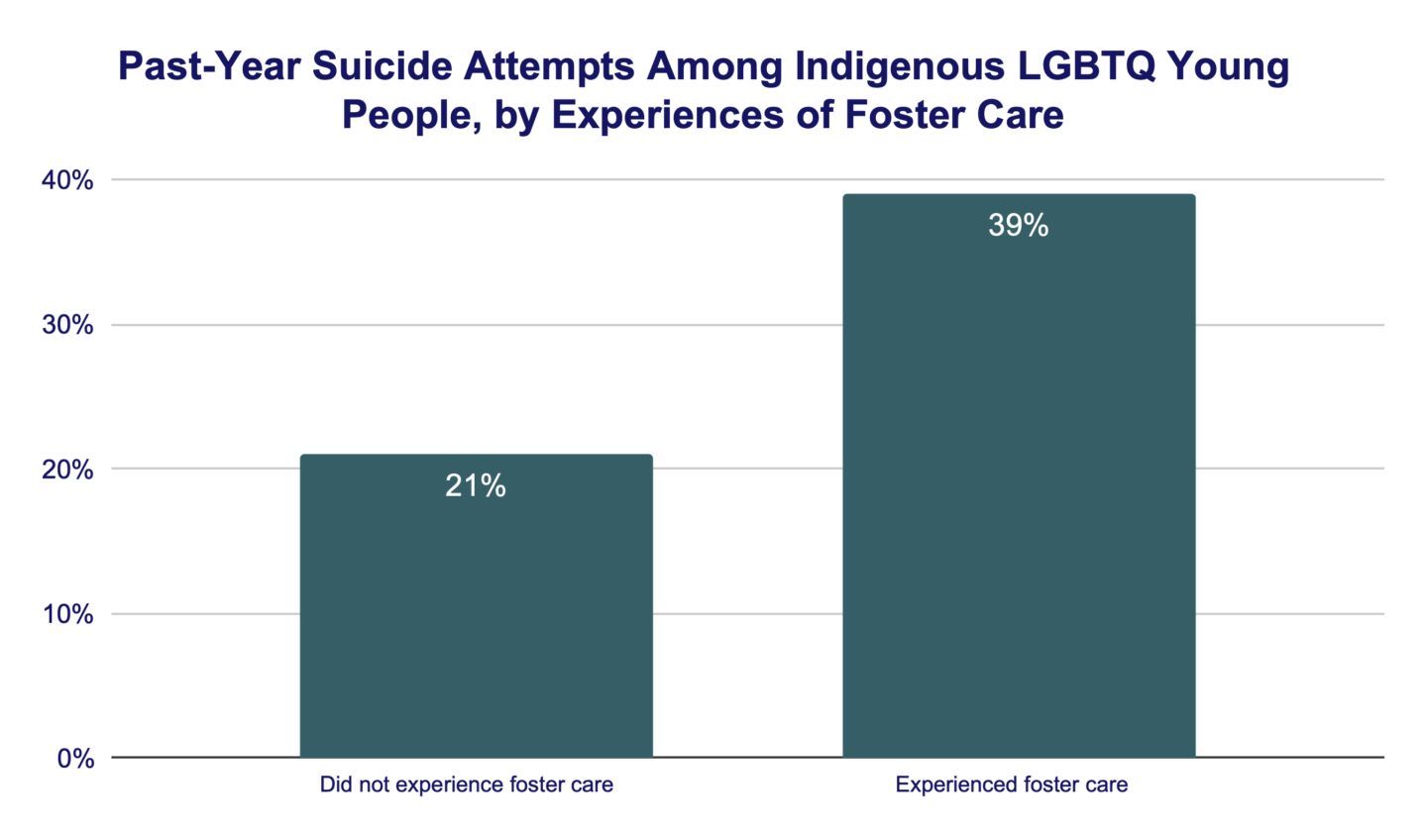

More than one in ten (12%) Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported experiences of being in foster care or residing in a group home, even if only briefly. In contrast, only 5% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people reported similar experiences. Having been in foster care or a group home was associated with higher rates of suicide risk. Nearly two in five (39%) Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported having been in foster care also reported past year suicide attempts, compared to only 21% of their Indigenous LGBTQ peers who did not report such experiences.

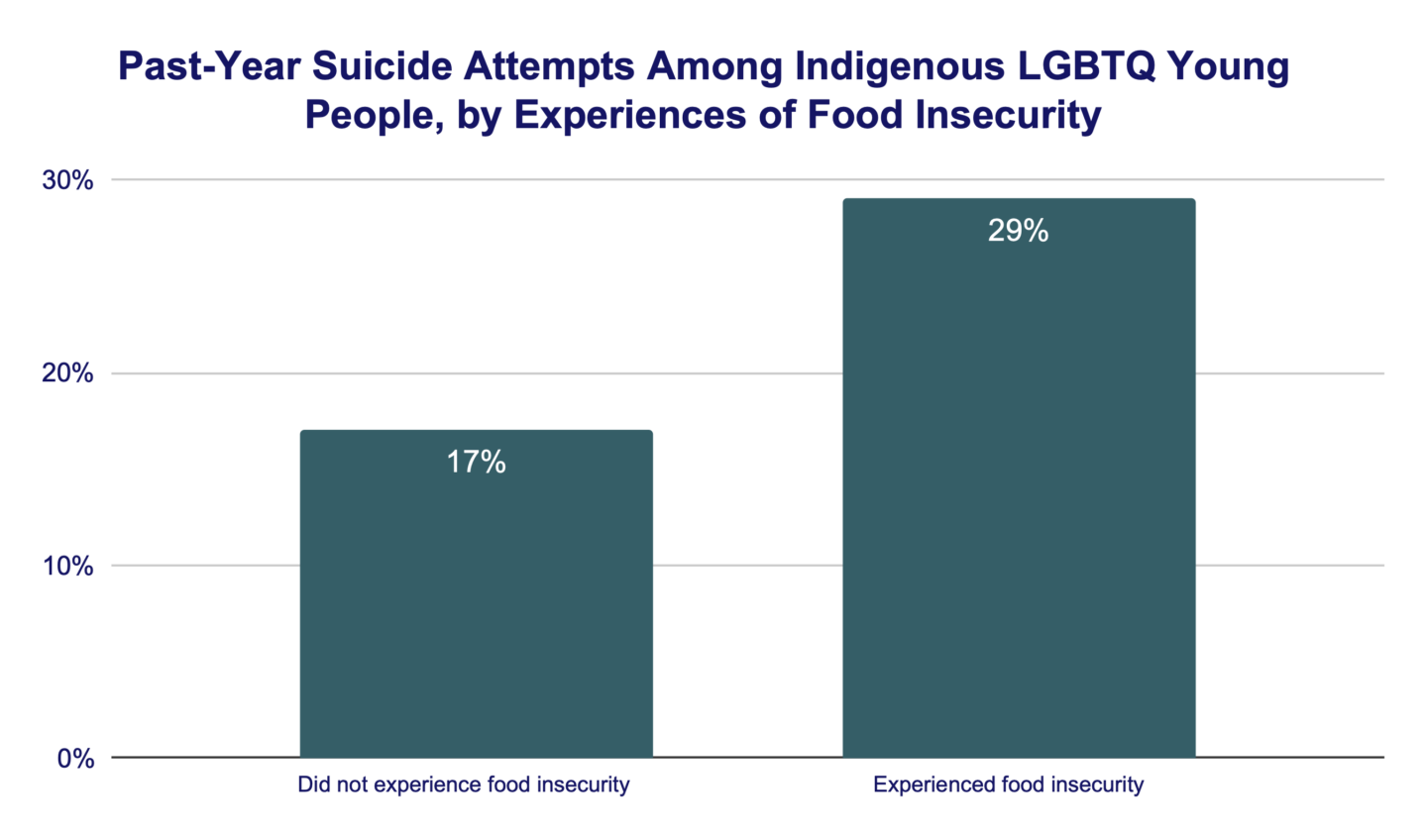

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity is defined as a scarcity of food or the disruption of eating patterns due to financial constraints or limited resources (Yousefi-Rizi et al., 2021). Nearly half of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported experiencing food insecurity, compared to just under a third of the broader sample LGBTQ young people (48% vs. 29%). Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people reported higher rates of food insecurity than their LGBQ cisgender peers (51% vs. 39%) as did Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 when compared to their older peers aged 18 to 24 (53% vs. 45%). Food insecurity was also associated with higher rates of suicide risk. Nearly a third of Indigenous LGBTQ young people who experienced food insecurity reported a suicide attempt in the past year (29%) compared to 17% of their Indigenous LGBTQ peers who did not report experiencing food insecurity.

Discrimination and Victimization

Discrimination

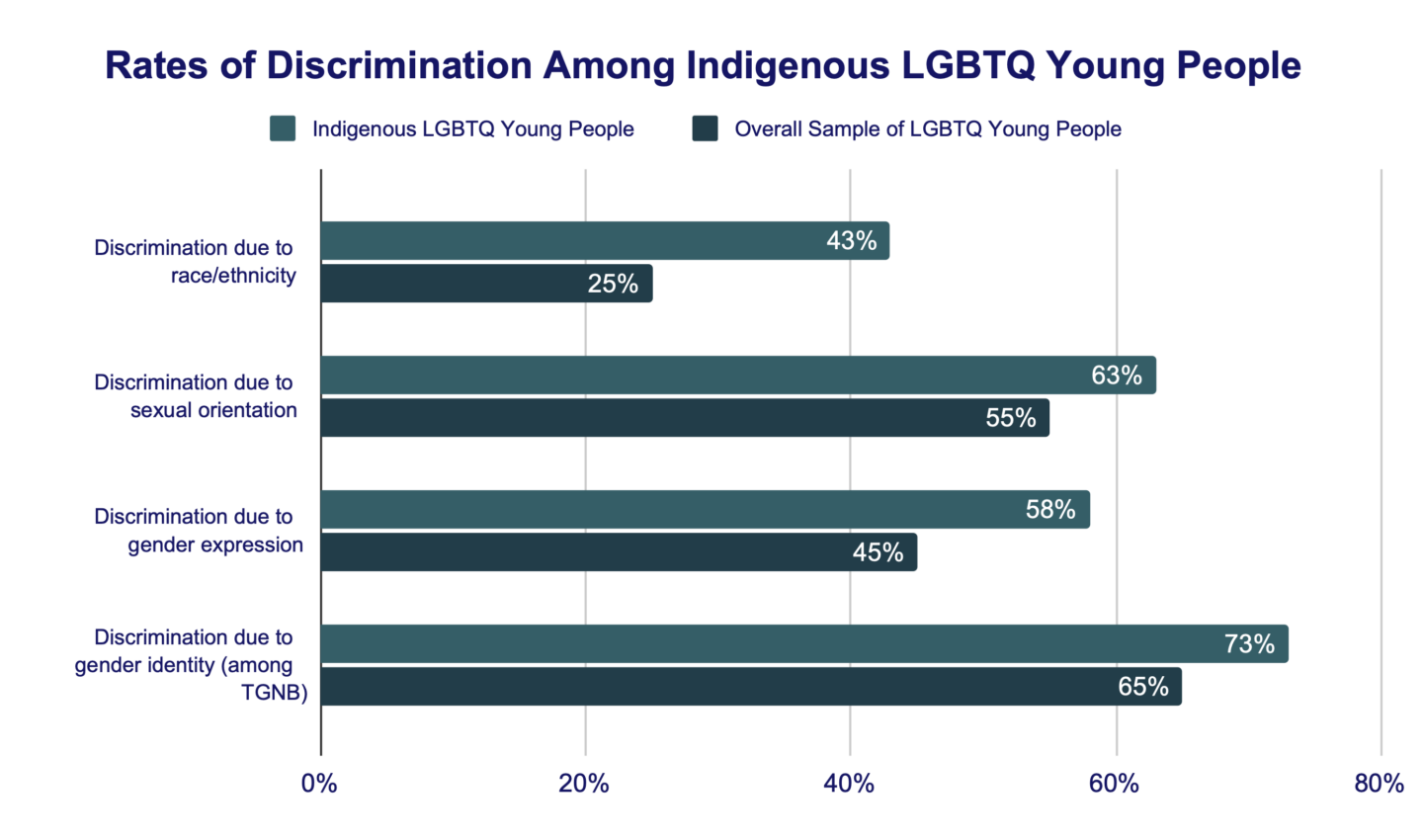

Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of anti-LGBTQ discrimination than the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. Nearly two-thirds of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (63%) reported experiencing discrimination due to their sexual orientation in the past year, compared to 55% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Nearly three-fourths of Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people (73%) reported experiencing discrimination due to their gender identity in the past year, compared to 65% of the overall sample of transgender and nonbinary young people. Over half of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (58%) reported experiencing discrimination due to their gender expression in the past year, compared to 45% of the broader sample of LGBTQ young people (sample included both transgender/nonbinary and cisgender identities). This is significant given the historical context of colonization, where Indigenous individuals were often punished for or prohibited from expressing their genders in traditional ways.

Anti-LGBTQ discrimination is not the only discrimination faced by Indigenous LGBTQ young people. Nearly half (43%) of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported experiencing discrimination due to their race or ethnicity in the past year. Multiracial Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported significantly higher rates of race-based discrimination in the past year (45%), compared to their LGBTQ peers who identified as exclusively Indigenous (36%).

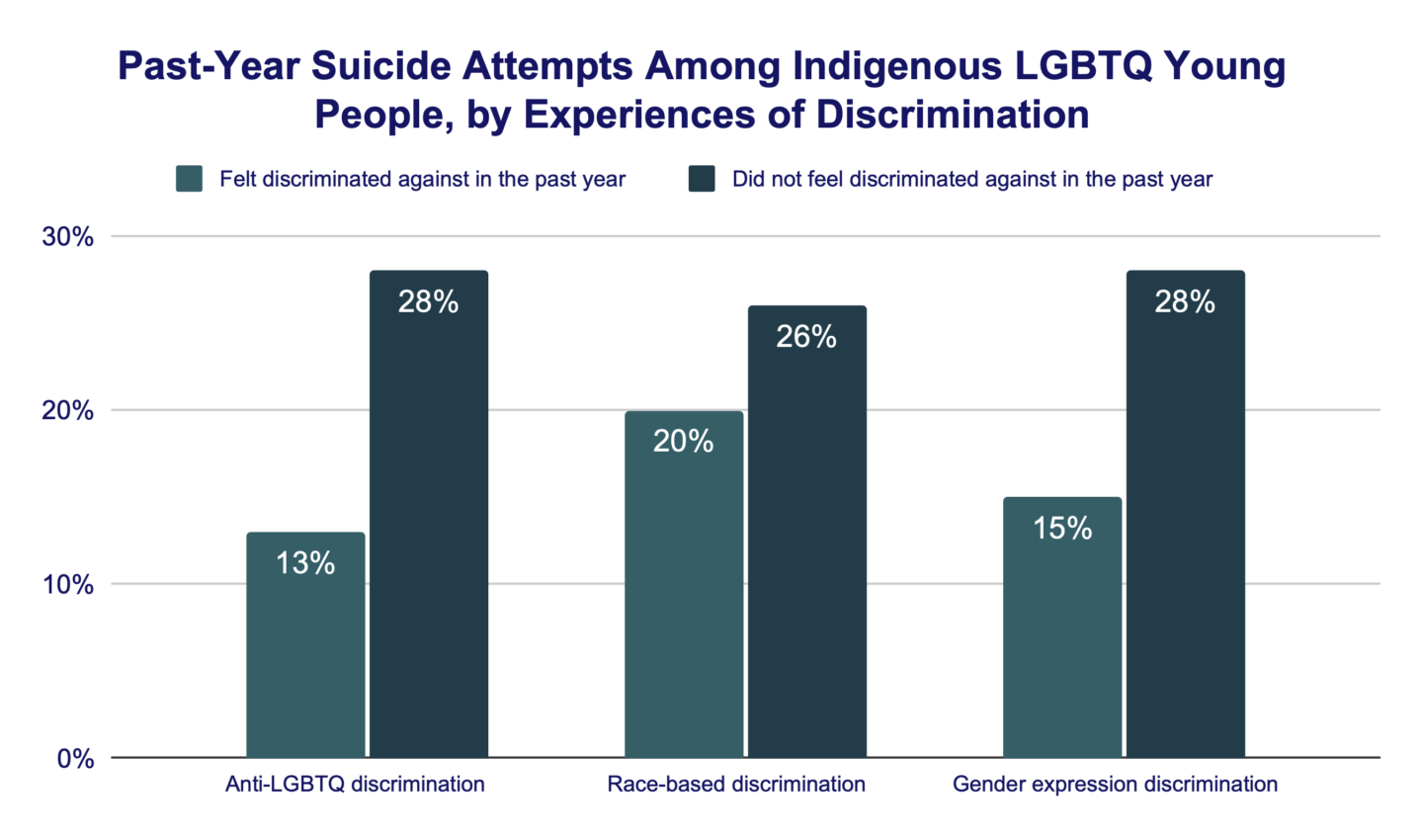

Experiencing discrimination in the past year is associated with higher suicide risk among Indigenous LGBTQ young people. Those who reported encountering anti-LGBTQ discrimination in the past year had more than twice the odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR= 2.26, 95% CI [1.60, 3.19], p<0.001) compared to their Indigenous LGBTQ peers who did not report such discrimination. Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported experiencing discrimination based on their gender expression in the past year had nearly one and a half times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR= 1.44 (1.10, 1.89), p<0.001) compared to Indigenous LGBTQ young people who did not report such discrimination. Finally, Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported experiencing race-based discrimination in the past year had over one and a half times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR= 1.66 (1.23, 2.26), p<0.001) compared to their Indigenous LGBTQ peers who did not report such discrimination.

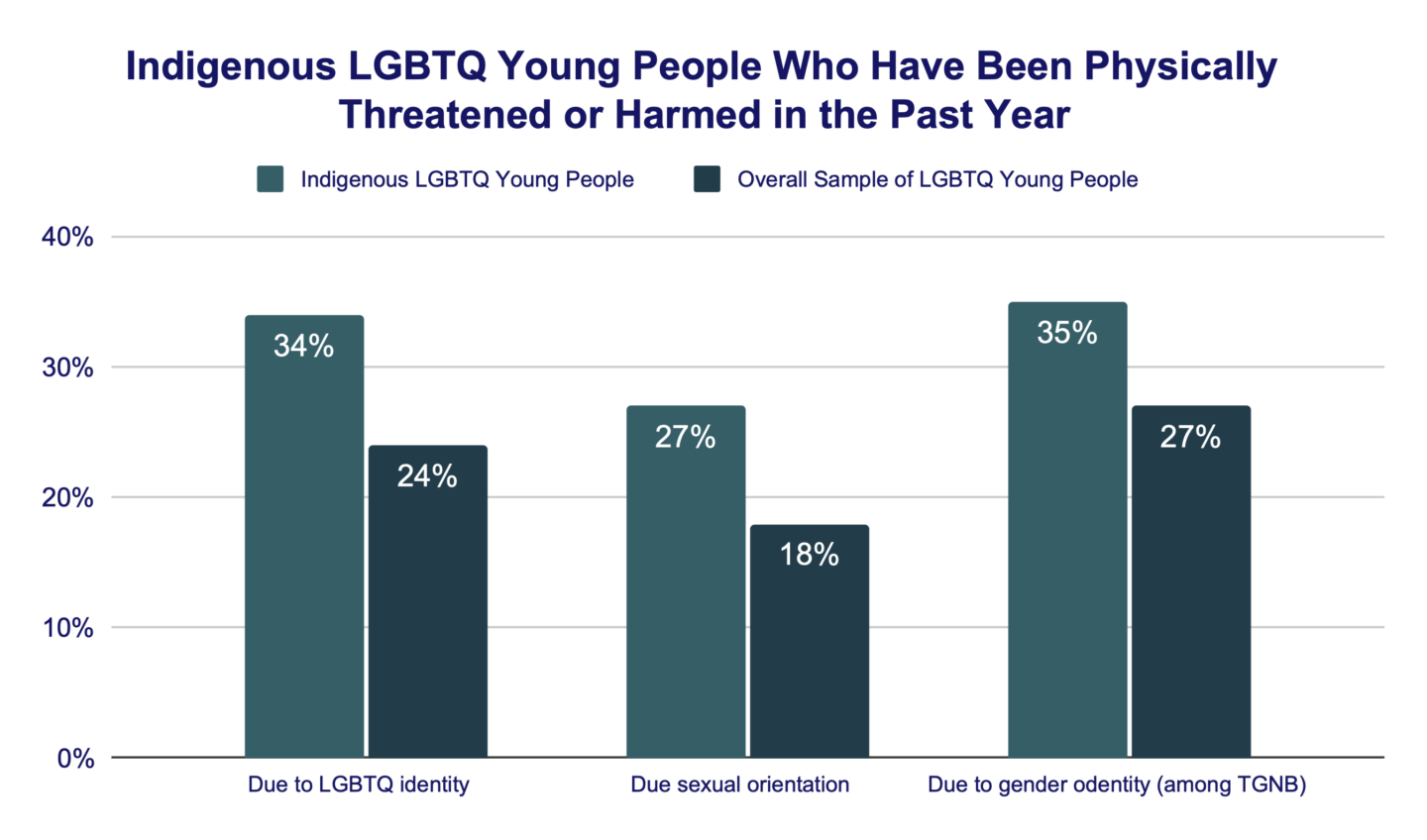

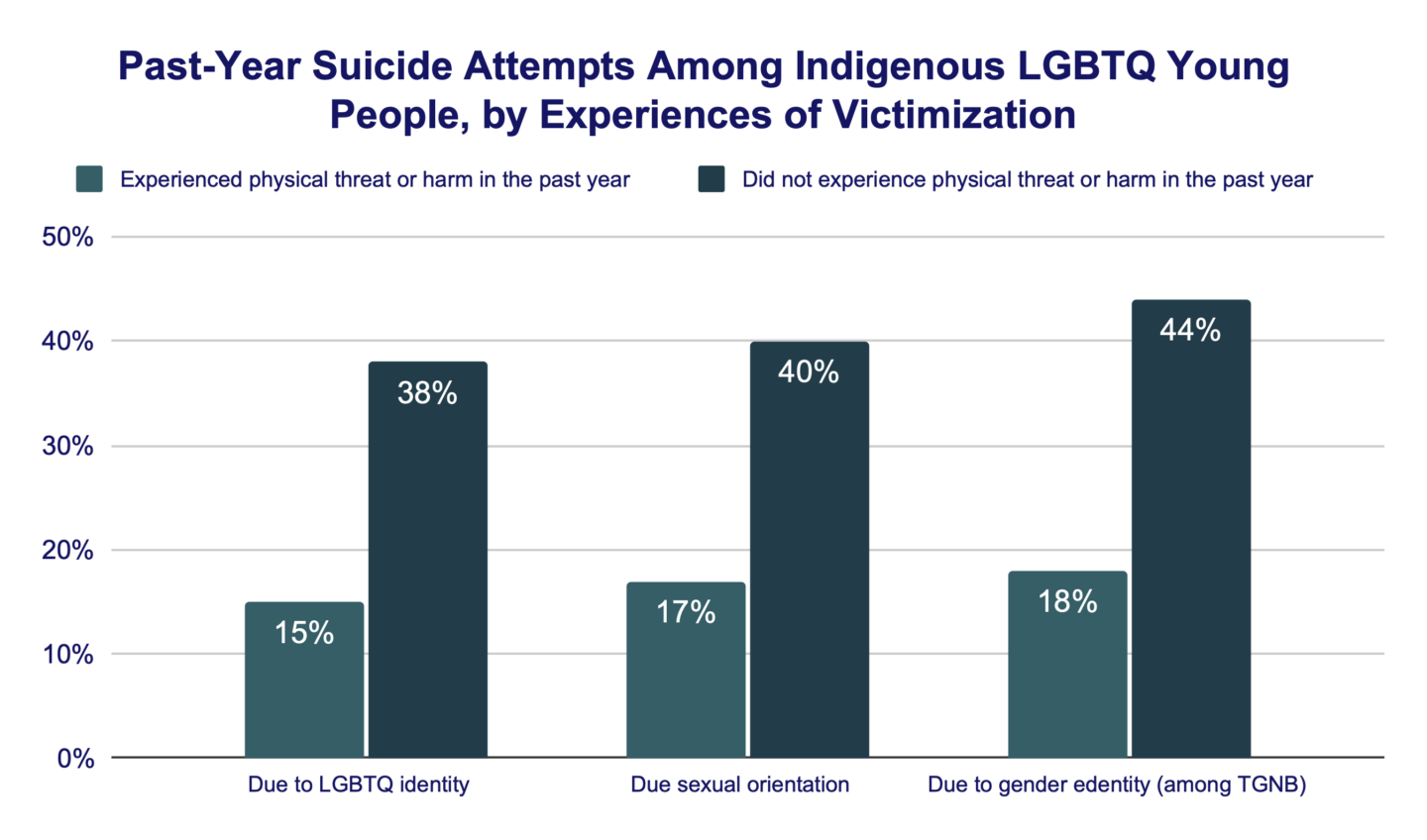

Victimization

Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of anti-LGBTQ victimization – being physically threatened or harmed due to one’s LGBTQ identity – than the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. Over a third of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (34%) reported being victimized due to their LGBTQ identity in the past year, compared to 24% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Over a quarter of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (27%) reported being victimized due to their sexual orientation in the past year, compared to 18% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Moreover, 35% of Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people reported being victimized due to their gender identity in the past year, in contrast to 27% among the wider sample of transgender and nonbinary young people.

Experiences of anti-LGBTQ victimization were associated with higher suicide risk among Indigenous LGBTQ young people. Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported being victimized due to their LGBTQ identity in the past year had over two and a half times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR=2.70, 95% CI [2.05, 3.58], p<0.001), compared to their Indigenous LGBTQ peers who did not report such victimization. Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported experiencing victimization specifically due to their sexual orientation in the past year had over two and a half times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR=2.61, 95% CI [1.95, 3.49], p<0.001), compared to their Indigenous LGBTQ peers who did not report such victimization. Furthermore, Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people who reported being victimized due to their gender identity in the past year had over three times greater odds of attempting suicide in the past year (aOR= 3.23, 95% CI [2.33, 4.47], p<0.001), compared to their Indigenous transgender and nonbinary peers who did not report such victimization.

Protective Factors

Supportive People

Friends and family are important sources of support for LGBTQ young people (Green et al., 2021; Price & Green, 2021), and Indigenous LGBTQ young people are no exception. Importantly, family support is associated with lower suicide risk. Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported high levels of general support (not LGBTQ-specific) from their families reported past-year suicide attempts at nearly half the rate compared to those who reported low to moderate levels of general family support (13% vs. 24%). However, Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported lower rates of general support from their family (19%) compared to the overall sample of LGBTQ young people (25%). Significantly lower rates of general family support were reported by Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people compared to their cisgender LGBQ peers (15% vs. 29%) and Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 compared to their older peers aged 18 to 24 (16% vs. 24%). Over two-thirds of Indigenous LGBTQ young people (67%) reported high levels of general support from their friends, although this was not significantly different from the overall sample nor was it associated with differences in suicide risk.

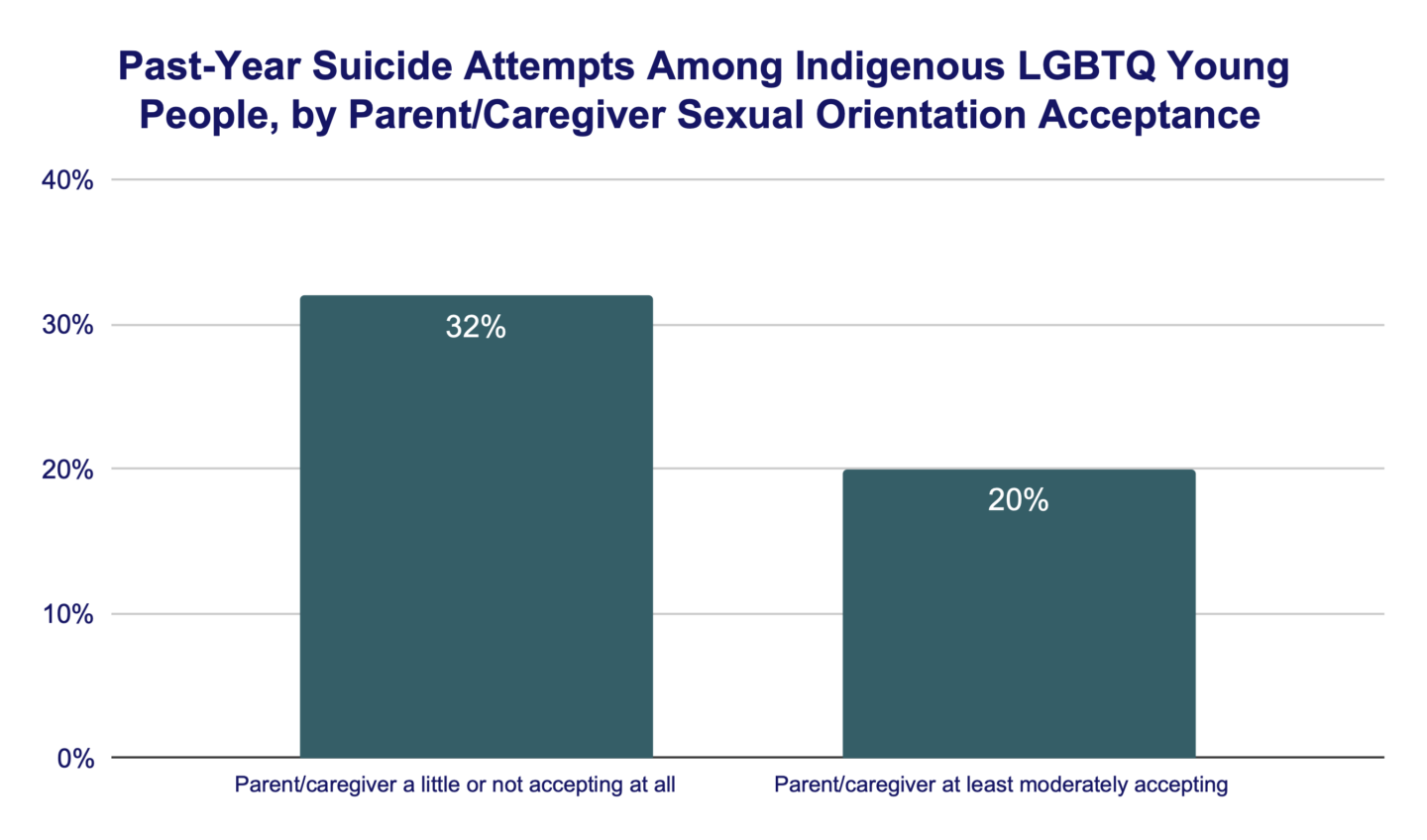

In terms of supporting a young person’s sexual orientation, 66% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported that their parent or caregiver was at least moderately accepting of their sexual orientation, which was not significantly different from the 69% of parents of caregivers observed in the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. Overall, 21% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people were not out to parents or caregivers about their sexual orientation, which was comparable to 28% of the overall sample of LGBTQ young people. Indigenous cisgender LGBQ young people reported significantly higher rates of parental sexual orientation support than their Indigenous transgender and nonbinary peers (77% vs. 63%). LGBTQ young people who identified as exclusively Indigenous reported significantly higher rates of parental sexual orientation support than their peers who identified as multiracial Indigenous (68% vs. 65%). Parental support for sexual orientation is associated with lower rates of suicide risk. One in five (20%) Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported that their parent or caregiver was at least moderately accepting of their sexual orientation reported a past-year suicide attempt, compared to 32% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people who said their parent or caregiver was only a little or not at all accepting of their sexual orientation.

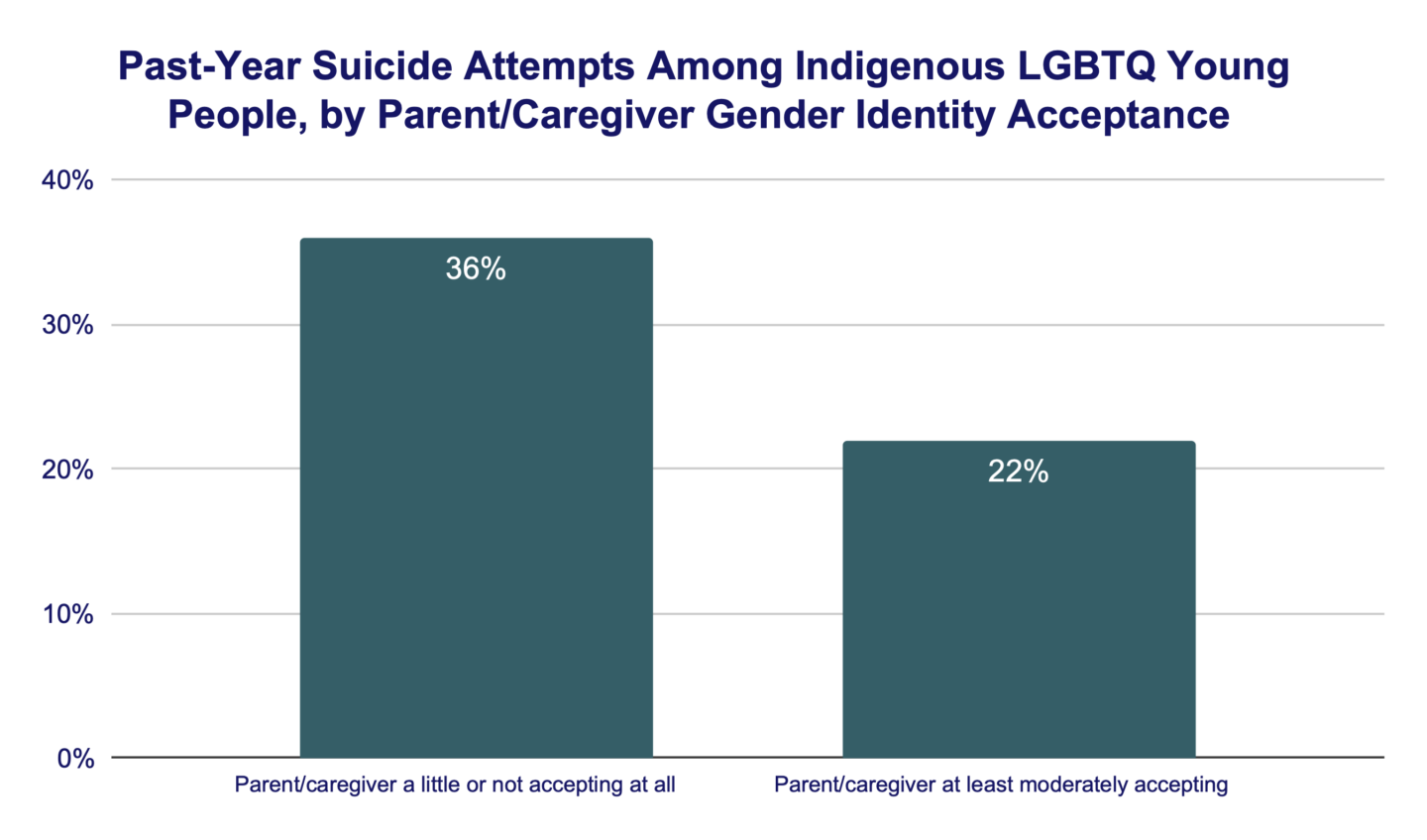

Similar trends were observed in parental support of a young person’s gender identity among Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people. A third of Indigenous transgender and nonbinary (33%) young people reported that they were not out to their parent or caregiver about their gender identity, compared to 40% of the overall sample of transgender and nonbinary young people. There were no significant differences in outness between age groups or race/ethnicity (exclusively Indigenous vs. multiracial Indigenous). Parental support for gender identity was associated with lower rates of suicide risk. Over one in five (22%) Indigenous transgender or nonbinary young people who felt their parent or caregiver was at least moderately accepting of their gender identity reported a past-year suicide attempt, compared to 36% of Indigenous transgender or nonbinary young people who said their parent or caregiver was only a little or not at all accepting of their gender identity.

Respect for pronouns is an important act of support for transgender and nonbinary young people and is associated with lower suicide risk among Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people. A quarter of Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people (25%) reported that all of the people who live with them respect their pronouns, while 22% reported that some of the people they live with respect their pronouns, and over half (51%) reported that none of the people they live with respect their pronouns. Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people who reported full pronoun respect, or that all of the people who live with them respect their pronouns, reported a past-year suicide attempt at nearly half the rate compared to those who reported no pronoun respect, or that none of the people who live with them respect their pronouns (17% vs 33%, respectively). Just over one in four Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people (26%) who reported some pronoun respect had attempted suicide in the past year.

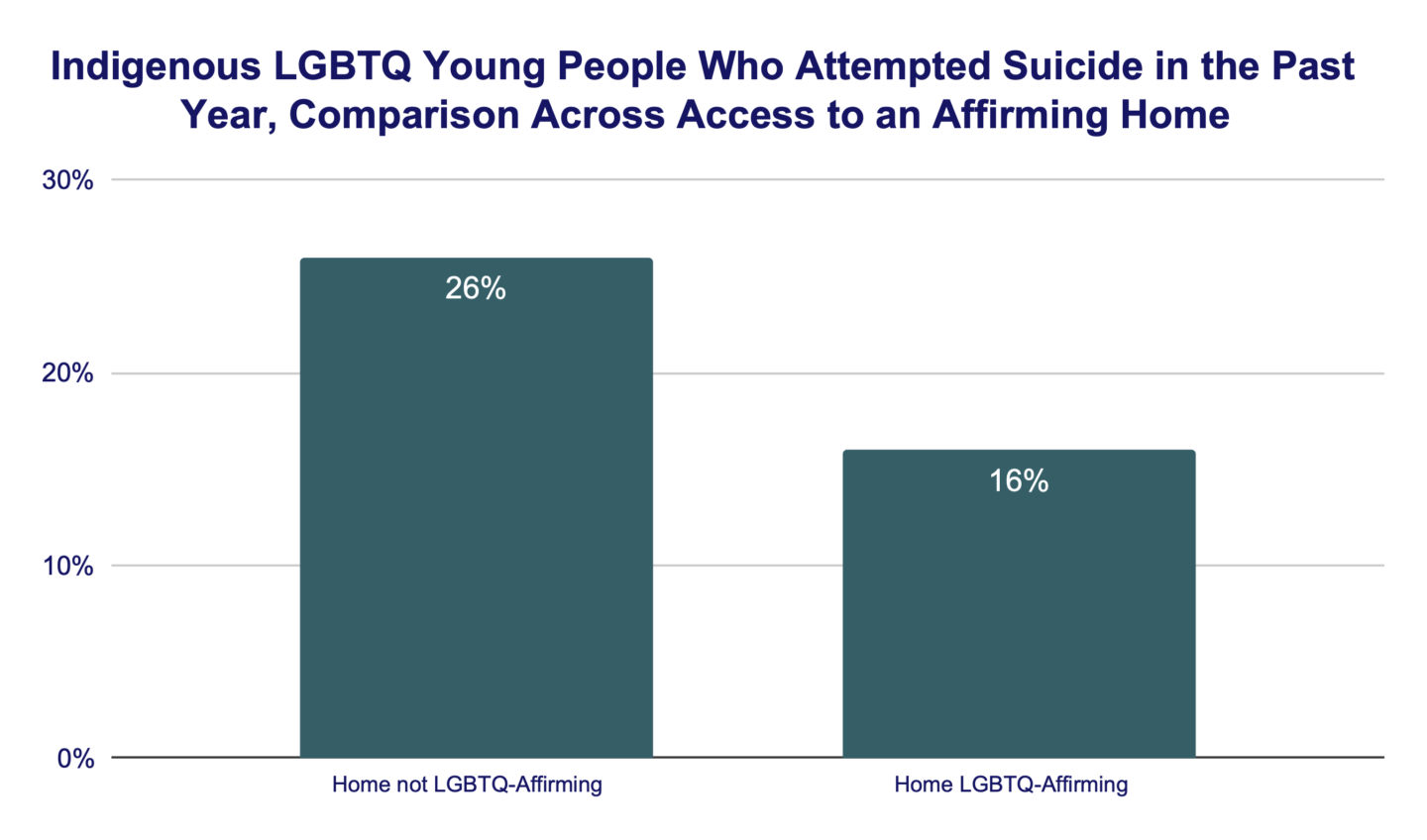

Supportive Places

A total of 38% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people indicated that their home was affirming of their LGBTQ identity, a figure which aligns with the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. However, Indigenous transgender and nonbinary young people reported significantly lower rates of their home being affirming than their cisgender LGBQ peers (35% vs. 48%) as did Indigenous LGBTQ young people aged 13 to 17 compared to their older peers aged 18 to 24 (29% vs. 53%). Living in an affirming home was associated with lower suicide risk. Only 16% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people with an affirming home reported attempting suicide in the past year compared to 26% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people who reported living in non-affirming homes. Notably, access to an affirming home was associated with 30% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year among Indigenous LGBTQ young people (aOR= 0.70, 95% CI [0.50, 0.97], p<0.05).

When examining other affirming spaces, 48% of Indigenous LGBTQ young people enrolled in school reported their school was affirming, 34% of those employed described their workplace as affirming, and 14% identified community events as affirming of their LGBTQ identity. These rates are not significantly different from the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. In addition, they did not differ significantly by gender identity or age, and they were not associated with significant differences in suicide risk.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our survey findings continue to demonstrate the sheer diversity among Indigenous LGBTQ young people found in previous studies. These findings show that Indigenous LGBTQ young people are diverse in regard to sexual orientation, gender identity, and background, both within their own group and compared to other LGBTQ young people. Among Indigenous LGBTQ young people in our sample, just over a quarter identified as exclusively Indigenous and three quarters identified as multiracial Indigenous. Over a quarter of Indigenous LGBTQ young people identified as Two-Spirit, and Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of gender diversity than the broader LGBTQ youth sample. Furthermore, Indigenous LGBTQ young people have rates of anxiety, depression, self-harm, seriously considering suicide, and attempting suicide that were significantly higher than the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. Despite these elevated rates, more than half of Indigenous LGBTQ young people who wanted psychological or emotional counseling were not able to get it. These findings are consistent with other scholarship documenting elevated mental health problems and suicide risk among Indigenous LGBTQ people (Robinson, 2022; Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto, 2018; Schuler et al., 2023) and highlight the urgent need for culturally-grounded mental health support for this particularly vulnerable population. Additionally, transgender and nonbinary Indigenous young people along with Indigenous young people aged 13 to 17 reported worse mental health outcomes and higher suicide risk relative to their cisgender LGBQ peers and peers aged 18 to 24, respectively. Such disparities highlight the need for accessible mental health services that are not only affirming of young people’s gender identities but are also developmentally appropriate for younger youth. Indigenous LGBTQ young people deserve mental health care that affirms and respects all aspects of their identities and lived experiences: their LGBTQ identities, their age, and their tribal cultures and traditions.

Indigenous LGBTQ young people face a number of challenges that impact their mental health. Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported high rates of anti-LGBTQ and race-based discrimination and violence. Both anti-LGBTQ discrimination and anti-LGBTQ victimization were associated with higher odds of reporting a past-year suicide attempt. They also reported higher rates of both formal conversion therapy and informal attempts to change their LGBTQ identity when compared to the broader sample of LGBTQ young people. This has important implications for Indigenous LGBTQ young people’s mental health, as experiencing either conversion therapy or change attempts were associated with higher odds of a past-year suicide attempt. Indigenous LGBTQ young people also reported higher rates of structural inequities such as homelessness, having been in foster care, and food insecurity. These findings align with other scholarly literature (Sarche & Spacer, 2008) and illustrate the lingering effects of historical trauma. The enduring impact of lost ancestral territories, the historical practice of forcibly removing children from their families, and the historical and contemporary under-investment in tribal communities have created extreme economic disadvantages for Indigenous individuals. Economically, a third of Indigenous LGBTQ young people reported that their household incomes were only sufficient enough to meet basic economic needs. This finding aligns with previous research about high rates of poverty among Indigenous people (Krogstad, 2014). There is an urgent need to decolonize and indigenize systems that oppress Indigenous LGBTQ young people and to increase funding to essential services like Native Health Services, which provide suicide intervention and prevention for Indigenous communities. This may include cultural competency training for healthcare providers and developing initiatives led by Indigenous communities, ensuring that suicide prevention strategies are culturally relevant and community-specific. Indigenous LGBTQ young people also reported high rates of anti-LGBTQ and race-based discrimination and violence. Both anti-LGBTQ discrimination and anti-LGBTQ victimization were associated with higher odds of reporting a past-year suicide attempt. These findings illuminate the interpersonal costs of White Supremacy and anti-LGBTQ bias, as well as the need to support Indigenous LGBTQ young people who have experienced discrimination, harassment, or violence.

Supportive families and affirming places offer a buffer for the negative experiences Indigenous LGBTQ young people face. Indigenous LGBTQ young people who indicated living in a home that affirms their LGBTQ identity had 30% lower odds of attempting suicide in the past year, compared to their Indigenous LGBTQ young people in non-affirming homes. These findings underscore the need for culturally-relevant resources to equip parents/caregivers of Indigenous LGBTQ young people to be able to better support the young people in their lives. This can include working with tribal leaders and institutions to provide culturally-specific education for parents about LGBTQ identities and how to support their children and prevent mental health symptoms or crises. Intergenerational trauma, especially trauma from residential boarding schools, may make it more challenging for Indigenous families to discuss emotions or LGBTQ topics. Culturally-grounded family therapy may be an effective intervention to help families support one another and their mental health. Indigenous LGBTQ young people also reported significantly higher rates of their religion or spirituality being important or very important to them than their non-Native LGBTQ peers. These findings align with other research on the importance and positive mental health effects of feeling connected to one’s ethnicity, traditions, and community (Ferlatte et al., 2019; Fieland et al. 2007; Meyer-Cook & Labelle, 2004; Taylor & Peter, 2011). Mental health practitioners working with Indigenous LGBTQ young people should leverage these protective factors in their work. More support is needed for mental health interventions grounded in Indigenous cultures and traditions.

More research is needed on the mental health needs of Indigenous LGBTQ young people. While our survey includes a large sample of Indigenous LGBTQ young people, it is not designed to capture the nuances and complexities of this diverse community. For example, we did not ask about Indigenous LGBTQ young people’s access to traditional practices or knowledge. Future research must consider the unique traditions and context, including the economics, of each tribal community. Historically, many Indigenous individuals and communities harbor distrust toward researchers due to a legacy of mistreatment by government and academic institutions. A notable instance includes the non-consensual sterilization of Indigenous women by the Indian Health Service (Pacheco et al., 2013). Community-based and Indigenous-led research can help build trust with communities and lead to more rigorous and accurate insights about Indigenous communities’ needs. Moreover, investigations employing large datasets and population studies should aim to capture more detail about Indigenous identities and experiences for more localized understandings of unique Indigenous communities. The Trevor Project is dedicated to improving the mental health and well-being of Indigenous LGBTQ young people. Our mission to end suicide among LGBTQ young people recognizes the inadequacy of a “one-size-fits-all” approach, understanding that each young person deserves affirmation in all aspects of their identity. Beyond this report, our efforts include an examination the mental health needs of Indigenous LGBTQ young people in our prior brief, American Indian/Alaskan Native Youth Suicide Risk. Our research team will continue efforts to explore and disseminate findings specific to Indigenous LGBTQ young people to support a better understanding of their unique experiences and address the mental health and well-being of Indigenous LGBTQ young people.

| The authors of this report acknowledge and extend our deepest thanks to Eustacia John for providing feedback and guidance on the creation of this report. |

About The Trevor Project

The Trevor Project is the leading suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, & questioning (LGBTQ) young people. The Trevor Project offers a suite of 24/7 crisis intervention and suicide prevention programs, including TrevorLifeline, TrevorText, and TrevorChat as well as the world’s largest safe space social networking site for LGBTQ young people, TrevorSpace. Trevor also operates an education program with resources for youth-serving adults and organizations, an advocacy department fighting for pro-LGBTQ legislation and against anti-LGBTQ policies, and a research team to examine the most effective means to help young LGBTQ people in crisis and end suicide. If you or someone you know is feeling hopeless or suicidal, our trained crisis counselors are available 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386, via chat TheTrevorProject.org/Help, or by texting 678-678.

This report is a collaborative effort from the following individuals at The Trevor Project:

Jonah P. DeChants, PhD

Senior Research Scientist

Myeshia N. Price, PhD

Director of Research Science

Ronita Nath, PhD

Vice President of Research

Steven Hobaica, PhD

Research Scientist

Kasey Suffredini

Interim Senior Vice President of Prevention

Recommended Citation: DeChants, J.P., Price, M.N., Nath, R., Hobaica, S., & Suffredini, K.(2023). The Mental Health and Well-Being of Indigenous LGBTQ Young People. The Trevor Project.

Media inquiries:

[email protected]

Research-related inquiries:

[email protected]

REFERENCES

- Alaers, J. (2010). Two-Spirited People and Social Work Practice: Exploring the History of Aboriginal Gender and Sexual Diversity. 11(1). https://doi.org/10.22329/csw.v11i1.5817.

- Baams, L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038994

- Balsam, K. F., Huang, B., Fieland, K. C., Simoni, J. M., & Walters, K. L. (2004). Culture, trauma, and wellness: a comparison of heterosexual and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and two-spirit native americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(3), 287. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.287

- Brooks VR: Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1981.

- Canadian Institutes for Health Research Institute of Gender and Health (2020). What and who is Two-Spirit? https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/igh_two_spirit-en.pdf

- Evans-Campbell, T., Walters, K. L., Pearson, C. R., & Campbell, C. D. (2012). Indian boarding school experience, substance use, and mental health among urban two-spirit American Indian/Alaska Natives. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 421–427. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.701358

- Fast, E., & Collin-Vézina, D. (2020). Historical trauma, race-based trauma and resilience of Indigenous peoples: A literature review. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(1), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069069ar

- Findling, M. G., Casey, L. S., Fryberg, S. A., Hafner, S., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of Native Americans. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1431–1441. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13224

- Ferlatte, O., Oliffe, J. L., Salway, T., Broom, A., Bungay, V., & Rice, S. (2019). Using photovoice to understand suicidality among gay, bisexual, and two-spirit men. Archives of sexual behavior, 48(5), 1529-1541.

- Fieland KC, Walters KL, & Simoni JM. (2007). Determinants of health among two-spirit American Indians and Alaska Natives. In The health of sexual minorities: public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. Edited by Meyerm IH, Springer:268–300.

- Forsythe, A., Pick, C., Tremblay, G., Malaviya, S., Green, A., & Sandman, K. (2022). Humanistic and economic burden of conversion therapy among LGBTQ youths in the United States. JAMA pediatrics, 176(5), 493-501.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0042

- Gaylor, E.G., Krause, K.H., Welder, LE., Cooper, A.C., Ashley, C., Mack, K.A., Crosby, A.E., Trinh, E., Ivey-Stephenson, A.Z., Whittle, L. (2023). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among high school students —Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 72, 45-54.

- Green, A. E., Price-Feeney, M., & Dorison, S. H. (2021). Association of sexual orientation acceptance with reduced suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning youth. LGBT health, 8(1), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0248

- Green, A. E., Price, M. N., & Dorison, S. H. (2022). Cumulative minority stress and suicide risk among LGBTQ youth. American journal of community psychology, 69(1-2), 157-168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12553

- Jacobs, S. E. (1997). Two-Spirit people: Native American gender identity. Sexuality, and spirituality. University of Illinois Press.

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Underwood, J. M.(2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students — 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

- Jones, N., Marks, R., Ramirez, R., & Rios-Vargas, M. (2020). Census illuminates racial and ethnic composition of the country. United States Census Bureau.

- Joseph, A. S. (2021). A modern trail of tears: The missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIW) crisis in the US. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 79, 102136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2021.102136

- Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., Truong, N. L., & Zongrone, A. D. (2020). The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/NSCS-2019-Full-Report_0.pdf

- Krogstad JM. One in 4 Native Americans and Alaskan natives are living in poverty. Fact Tank Pew Research Center. June 13, 2014. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2014/06/13/1-in-4-native-americans-and-alaska-natives-are-living-in-poverty Accessed Oct 20, 2023.

- Lehavot, K., Walters, K. L., & Simoni, J. M. (2009). Abuse, mastery, and health among lesbian, bisexual, and two-spirit American Indian and Alaska Native women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(3), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013458

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Meyer-Cook, F., & Labelle, D. (2004). Namaji: two-spirit organizing in Montreal, Canada. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 16(1), 29-51.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Social determinants of health. Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople

- Pacheco, C. M., Daley, S. M., Brown, T., Filippi, M., Greiner, K. A., & Daley, C. M. (2013). Moving forward: Breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2152–2159.https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301480

- Pellicane, M. J., & Ciesla, J. A. (2022). Associations between minority stress, depression, and suicidal ideation and attempts in transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 91, 102113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102113

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

- Price, M. N., Green, A.E, & Davis, C. (2021). Multisexual Youth Mental Health: Risk and Protective Factors for Youth Who are Attracted to More than One Gender. The Trevor Project.

- Price, M. N., & Green, A. E. (2021). Association of gender identity acceptance with fewer suicide attempts among transgender and nonbinary youth. Transgender Health, X:X, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0079

- Price, M. N., DeChants, J. P., & Davis, C. K. (2022).The mental health and well-being of multiracial LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

- Price, M. N., Green, A. E., DeChants, J. P., & Davis, C. K. (2021).The mental health and well-being of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

- Price, M.N., Nath, R., DeChants, J.P., Hobaica, S., Suffredini, K.(2023). The Mental Health and Well-Being of Latinx LGBTQ Young People. The Trevor Project.

- Price-Feeney, M, Green, A.E. & Dorison, S. (2020). All Black lives matter: Mental health of Black LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project.

- Price-Feeney, M., Green, A. E., & Dorison, S. (2020). Understanding the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), 684–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.11.314

- Pruden, H. (2019). Two-Spirit conversations and work: Subtle and at the same time radically different. In A. Devor, A.H. Thomas (Eds.), Transgender: A reference handbook (pp. 134-137). ABC-CLIO. Santa Barbara, CA.

- Pruden, H. (2020). TWO-SPIRIT turns 40!! Two Spirit Journal. Available at: https://twospiritjournal.com/?p=973 Accessed on Oct 20, 2023.

- Richardson, L. P., Rockhill, C., Russo, J. E., Grossman, D. C., Richards, J., McCarty, C., McCauley, E., & Katon, W. (2010). Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 126(6), 1117–1123. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0852

- Robinson, M. (2022). Recent insights into the mental health needs of two-spirit people. Current Opinion in Psychology, 48, 101494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101494

- Sarche, M., & Spicer, P. (2008). Poverty and health disparities for American Indian and Alaska Native children: Current knowledge and future prospects. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136, 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.017

- Schuler, A., Wedel, A., Kelsey, S. W., Wang, X., Quiballo, K., Beatrice Floresca, Y., Phillips, G., & Beach, L. B. (2023). Suicidality by sexual identity and correlates among American Indian and Alaska Native high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.07.020

- Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto. (2018). Our health counts Toronto: two-spirit mental health. Seventh Generation Midwives; http://www.welllivinghouse.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/ 02/Two-Spirit-Mental-Health-OHC-Toronto-1.pdf.

- Sium, A., Desai, C., & Ritskes, E. (2012). Towards the ‘tangible unknown’: Decolonization and the Indigenous future. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), I–XIII.

- Taylor, C., & Peter, T. (2011). Every class in every school: Final report on the first national climate survey on homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia in Canadian schools. Egale Canada Human Rights Trust.

- Walters, K. L., Evans-Campbell, T., Simoni, J. M., Ronquillo, T., & Bhuyan, R. (2006). “My spirit in my heart”: Identity experiences and challenges among American Indian two-spirit women. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 10(1–2), 125–149. https://doi.org/10.1300/J155v10n01_07

- Walters, K. (2010). Critical Issues and LGBT-Two Spirit Populations: Highlights from the HONOR Project Study. Indigenous Wellness Research Institute, University of Washington.

- Woolford, A., Benvenuto, J., & Hinton, A. L. (Eds.). (2014). Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822376149

- Yousefi-Rizi, L., Baek, J. D., Blumenfeld, N., & Stoskopf, C. (2021). Impact of housing instability and social risk factors on food insecurity among vulnerable residents in San Diego County. Journal of Community Health, 46, 1107–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-00999-w

- Zongrone, A. D., Truong, N. L., & Kosciw, J. G. (2020). Erasure and resilience: The experiences of LGBTQ students of color, Native American, American Indian, and Alaska Native LGBTQ youth in U.S. schools. New York: GLSEN.

| Table 1: Indigenous LGBTQ Young People Characteristics | |||

| Age (n =1,792) | Race and Ethnicity (n = 1,792) | ||

| Under 18 | 35% | Exclusively Indigenous | 26% |

| 18 and over | 65% | Multracial Indigenous | 74% |

| Sexual Orientation (n = 1,777) | Tribal Affiliation (n = 361) | ||

| Bisexual | 25% | Cherokee | 12% |

| Pansexual | 25% | Choctaw | 2% |

| Lesbian | 13% | Navajo | 2% |

| Queer | 12% | Ojibwe | 1% |

| Asexual | 11% | Pronouns (n = 1,782) | |

| Gay | 11% | She or he only | 36% |

| I am not sure | 5% | Pronouns outside of the gender binary | 64% |

| Straight | 0.4% | Just Meeting Basic Needs (n = 1,015) | 34% |

| Gender Identity (n = 1,752) | Region (n = 1,792) | ||

| Nonbinary | 47% | South | 36% |

| Cisgender woman | 22% | West | 32% |

| Transgender man | 16% | Midwest | 24% |

| Questioning | 7% | Northeast | 9% |

| Cisgender man | 5% | U.S. Immigrant Status | |

| Transgender woman | 3% | Youth born outside of the U.S. (n =1,783) | 3% |

| Speak a Language Other Than English at Home (n= 1,754) | 4% | At least one parent/caregiver born outside of the U.S. (n =1,757) | 16% |

© The Trevor Project 2023