Background

LGBTQ+ young people are more likely to report mental health concerns, such as symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as suicidality, in comparison to their straight and cisgender peers (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020). These mental health issues are often tied to experiences of minority stress, a term coined to describe the unique stressors encountered by individuals with marginalized identities (Meyer, 2003; Rich et al., 2020). A meta-synthesis conducted by Duke (2011) found that LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities experience discrimination, a form of minority stress, in numerous contexts due to their various identities (e.g., sexual orientation, gender identity, disability). Disabilities can include “emotional and behavioral disorders, physical disabilities, as well as developmental and learning disabilities” (Turner et al., 2011, p. 1). As a result of minority stress, these experiences of discrimination place them at a higher risk for mental health concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety, suicidality). Prior publications by The Trevor Project found that LGBTQ+ young people with autism, as well as those who were Deaf (i.e., broad term for all forms of deafness), report heightened rates of mental health concerns compared to their allistic or hearing LGBTQ+ peers, respectively (The Trevor Project, 2022ab), likely tied to these experiences of minority stress. It is also well-documented that LGBTQ+ people and people with disabilities have faced systemic oppression and discrimination for decades, which has impacted their health (Rodríguez-Roldán, 2020). However, limited research has quantitatively explored the mental health and experiences of LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities using a large, national sample. This brief will expand upon previous work by examining differences in reported disability and exploring the relationship between disability-related variables and mental health among LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities, using data from The Trevor Project’s 2023 National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ+ Young People.

Results

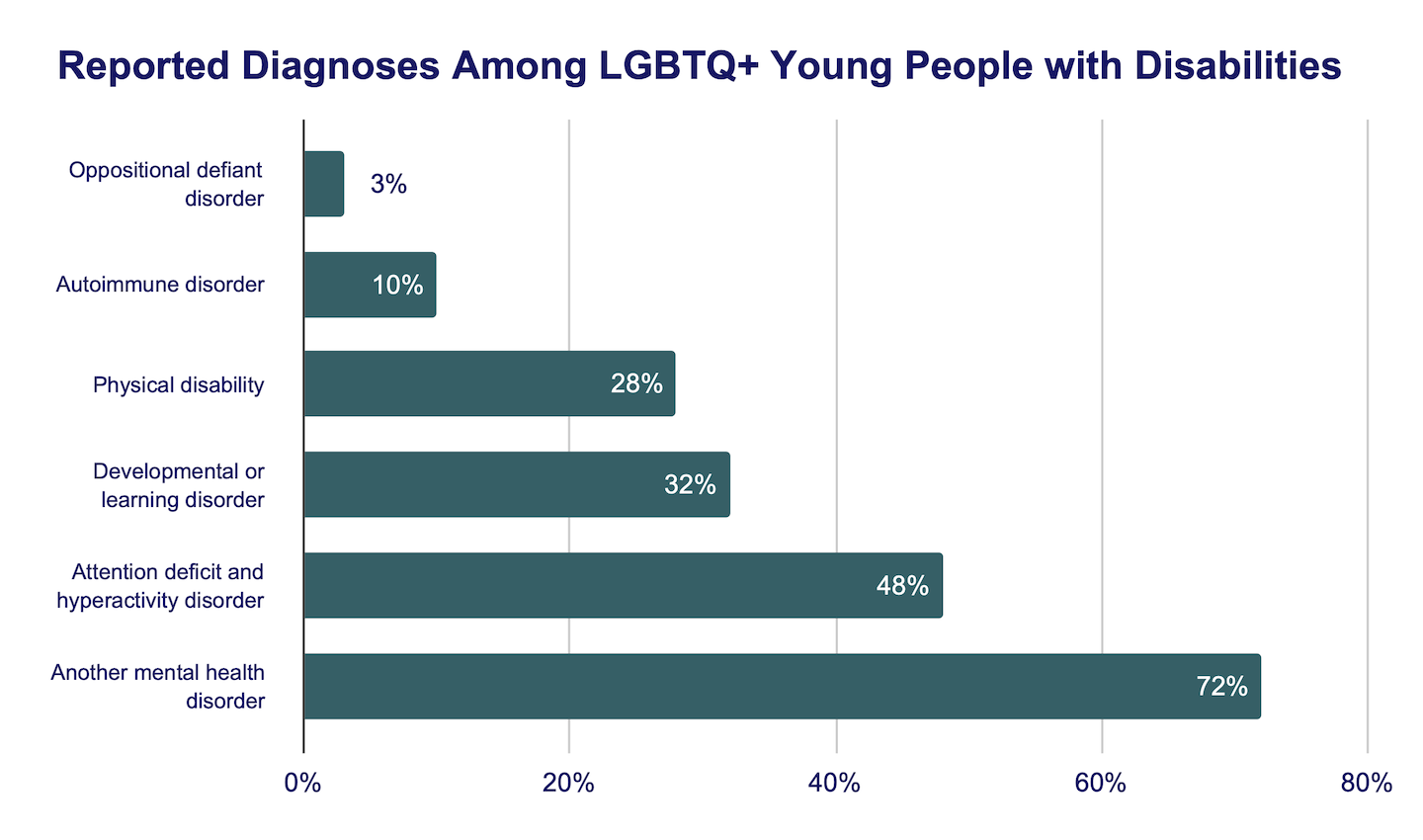

In the overall sample of LGBTQ+ young people, nearly one third (29%) identified as someone with a disability. Within this group, specific diagnoses were reported, aligning with categories commonly recognized as disabilities by health professionals and the academic literature (Turner et al., 2011). For instance, of those who reported having a disability, 48% reported being diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), 32% with a developmental or learning disorder (e.g., Autism Spectrum Disorder, Specific Learning Disorder), 28% with a physical disability (i.e., physical health or medical problem affecting daily living), 10% with an autoimmune disorder (e.g., HIV, Diabetes, Lupus, Rheumatoid Arthritis), 3% with Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and 72% with another mental health disorder (e.g., Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder). Notably, 31% reported having a single diagnosis from the aforementioned categories, 37% had two diagnoses, and 32% had three or more diagnoses.

Different demographic groups reported varying rates of disability identification. Older LGBTQ+ young people aged 18 to 24 reported identifying as someone with a disability more frequently (37%) compared to their younger peers aged 13 to 17 (25%). Regarding sexual orientation and gender identity, those identifying as multisexual (e.g., bisexual, pansexual, queer; 29%) and transgender or nonbinary (36%) reported higher rates of disability than their monosexual (e.g., gay, lesbian; 27%) and cisgender (18%) peers. More specifically, rates of having a disability were highest among queer (38%), asexual (37%), and gender diverse young people who were assigned female at birth (i.e., transgender boys and men (41%) and nonbinary individuals (40%)). Although White LGBTQ+ young people generally reported higher rates of disability compared to their peers of color (30% vs. 28%), when examining specific identities, Native/Indigenous (36%) and multiracial (35%) LGBTQ+ young people reported the highest rates.

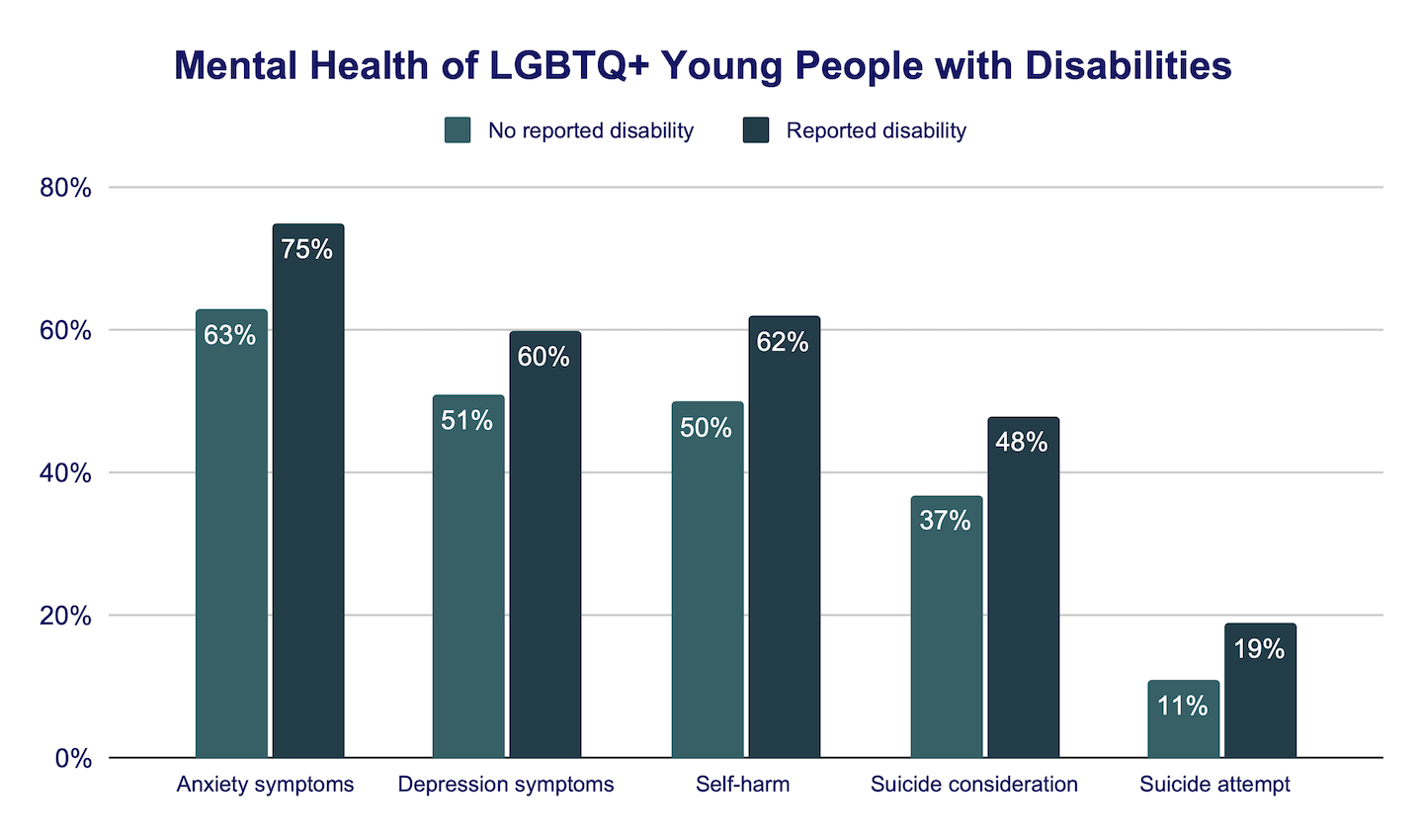

LGBTQ+ young people who identified as someone with a disability reported higher rates of mental health symptoms and suicidality in comparison to their peers who did not. Among those who reported having a disability, higher rates of recent depression (60% vs. 51%) and anxiety (75% vs. 63%), as well as seriously considering suicide (48% vs. 37%) and attempting suicide (19% vs. 11%) in the past year, were observed compared to LGBTQ+ young people without disabilities. LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities had over one and a half times the odds of reporting a suicide attempt in the past year compared to LGBTQ+ peers without disabilities (aOR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.60-1.91, p < 0.001).

Just under two thirds (65%) of LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities reported feeling discriminated against for their actual or perceived disability in the past year. LGBTQ+ young people with a disability who were discriminated against for their actual or perceived disability reported higher rates of recent depression (65% vs. 52%) and anxiety (80% vs. 66%) compared to those who were not. Additionally, they reported higher rates of attempting suicide in the past year (23% vs. 11%). LGBTQ+ young people who reported having a disability and experiencing disability-related discrimination had nearly two and a half times higher odds of reporting a suicide attempt in the past year compared to their LGBTQ+ peers with a disability but no reported disability-related discrimination (aOR = 2.38, 95% CI = 2.02-2.80, p < 0.001).

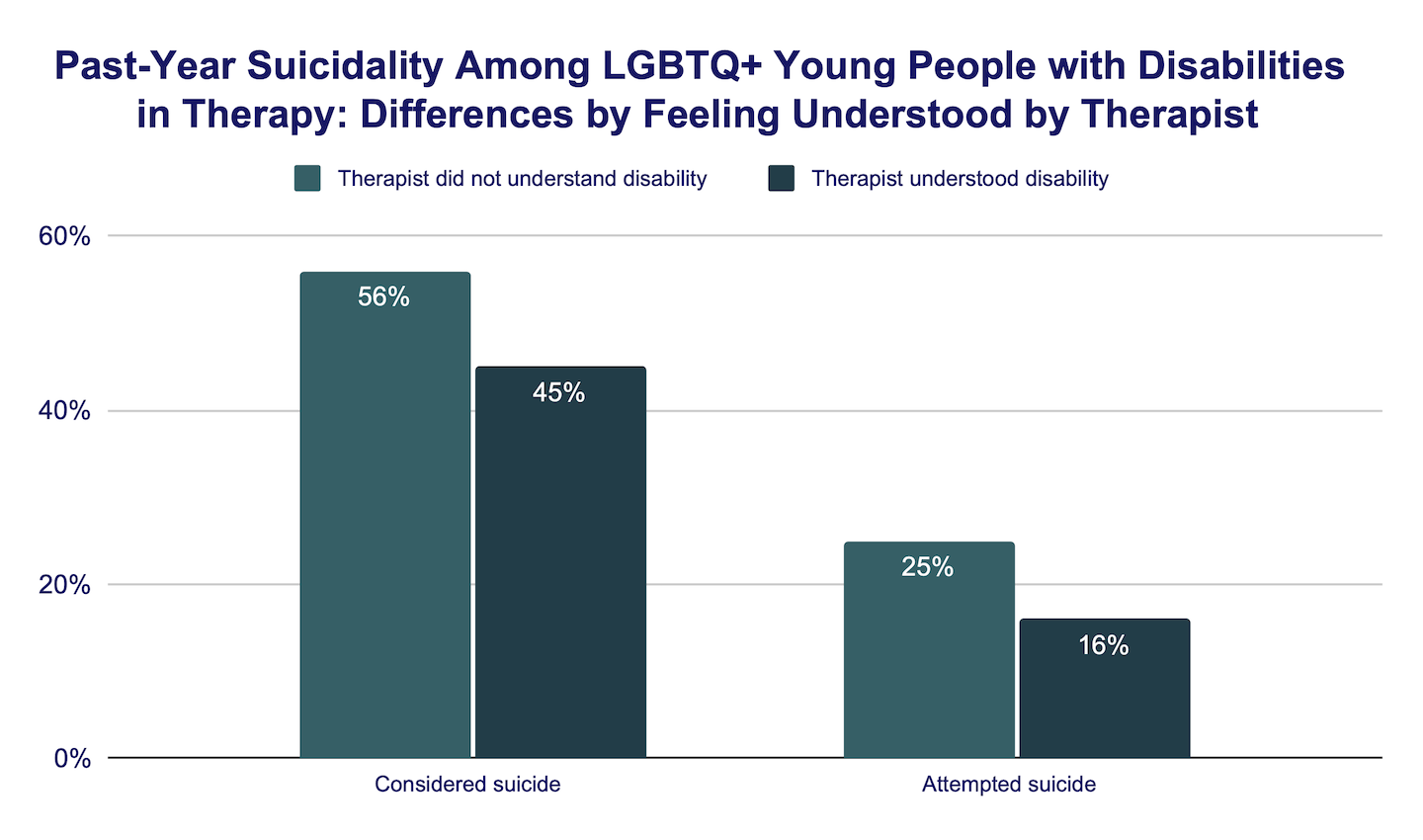

After obtaining therapy, nearly two thirds (68%) of LGBTQ+ young people with a disability felt their therapist understood their disability somewhat or a lot, which was related to lower rates of suicide attempts in the past year. Compared to peers who felt their therapist understood their disability a little or not at all, LGBTQ+ young people who felt understood by their therapist reported lower rates of considering (45% vs. 56%) and attempting (16% vs. 25%) suicide in the past year. LGBTQ+ young people with a disability who went to therapy and felt their disability was understood had 30% lower odds of a past-year suicide attempt compared to those who had a therapist that did not understand their disability (aOR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.60-0.83, p < 0.001).

Methods

Data were collected through The Trevor Project’s 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People. In total, 28,524 LGBTQ+ young people between the ages of 13 to 24 were recruited via targeted ads on social media. For analyses with LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities, 7,780 (29% of the sample) identified as a “disabled person or someone with a disability” and were included.

Questions assessing past-year suicidality were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Johns et al., 2020). Participants were also asked “Do you identify as a disabled person or a person with a disability?” and could answer Yes or No. Regarding diagnoses, they were asked “Has a health professional ever diagnosed you with any of the following conditions? Please select all that apply” followed by a list of different diagnoses to select. Additionally, they were asked “During the past 12 months, have you felt discriminated against for your actual or perceived physical or mental disability?” and could answer Yes or No. Finally, for those who had been to therapy, they were asked “How well did the counselor(s) or mental health care professional(s) you talked to understand your disability(ies)?” and could answer Not at all, A little bit, Somewhat, and A lot. For analysis, this item was dichotomized into Did not Understand (Not at all, A little bit) and Understood (Somewhat, A lot). Chi-square tests were used to examine differences between groups. All reported comparisons are statistically significant at least at p < 0.05. This means there is less than a 5% likelihood these results occurred by chance. After checking necessary assumptions, adjusted logistic regression models were run to determine the association between disability variables and suicidality in the past year, controlling for age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and socioeconomic status.

Looking Ahead

These findings suggest that LGBTQ+ young people report high rates of having a disability, and that these rates vary depending on demographic factors. For example, young people who identified as queer, asexual, transgender boys/men, and nonbinary (assigned female at birth) reported the highest rates of having a disability, as did older individuals (ages 18 to 24), and those identifying as Native/Indigenous or multiracial. Additionally, our data revealed that LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities reported higher rates of mental health concerns in comparison to their peers without disabilities. These heightened rates are likely related to compounding experiences of minority stress due to their LGBTQ+ identity (Meyer, 2003) and disability (Lund, 2020).

Our data also highlighted risk and protective factors for LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities. The majority of individuals who reported having a disability also reported being discriminated against in regard to their disability in the past year. These experiences of discrimination were consistently related with increased rates of mental health concerns, including suicide attempts, when compared to their peers with disabilities who did not experience such discrimination. On the other hand, LGBTQ+ young people who accessed therapy to assist with their mental health concerns and felt their therapists understood their disability reported lower rates of past-year suicide attempts compared to peers whose therapist lacked such understanding. These findings highlight the importance of preventing individual and systemic discrimination against LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities, as well as providing access to disability-informed mental health services to those in need.

Future research on LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities should examine the mental health of individuals with specific disabilities and comorbidities. Additionally, longitudinal and intervention work is always recommended, whenever possible. Given the high prevalence of disability-related discrimination and its relationship with poor mental health, proactive interventions at both personal and structural levels are imperative. Furthermore, providing adequate training to mental health providers on understanding and working with LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities is critical. For those interested in learning more on how to support LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities, The Trevor Project has published a guide on Supporting LGBTQ Young People with Disabilities and a blog on Being There for LGBTQ Young People with Disabilities.

At The Trevor Project, our Crisis Services team works 24/7 to help LGBTQ young people in crisis, including LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities. We also provide training to LGBTQ+-facing adults, including professionals who work with young people (e.g., counselors, educators, nurses, social workers), as a means to increase understanding of LGBTQ+ people with disabilities, as well as provide guidance on trauma-informed suicide prevention efforts that are applicable to individuals with disabilities. Additionally, Trevor’s Research team is committed to the ongoing dissemination of research that explores the experiences of LGBTQ+ young people with disabilities as a means to prevent suicide for a particularly vulnerable community.

Recommended Citation: The Trevor Project. (2023). The Mental Health of LGBTQ+ Young People with Disabilities.

References

- Duke, T. S. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth with disabilities: A meta-synthesis. Journal of LGBT Youth, 8(1), 1-52. DOI: 10.1080/19361653.2011.519181

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., & Underwood, J. M. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 States and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R. R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., Suarez, N., & Underwood, J. M. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students — youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69(Suppl-1), 19–27. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3external

- Lund, E. M. (2021). Examining the potential applicability of the minority stress model for explaining suicidality in individuals with disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 66(2), 183. DOI: 10.1037/rep0000378

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- National Institutes of Health. (2023). Writing respectfully: Person-first and identity-first language.

- Rich, A. J., Salway, T., Scheim, A., & Poteat, T. (2020). Sexual minority stress theory: Remembering and honoring the work of Virginia Brooks. LGBT health, 7(3), 124-127. DOI: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0223

- Rodríguez-Roldán, V. M. (2019). The Intersection between Disability and LGBTQ Discrimination and Marginalization. Am. UJ Gender Soc. Pol’y & L., 28, 429. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/jgspl/vol28/iss3/2

- The Trevor Project.a (2022). Mental health among autistic LGBTQ youth.

- The Trevor Project.b (2022). Mental health of Deaf* LGBTQ youth.

- The Trevor Project. (2023). 2023 U.S. national survey on the mental health of LGBTQ young people. [Data set].Turner, H. A., Vanderminden, J., Finkelhor, D., Hamby, S., & Shattuck, A. (2011). Disability and victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Maltreatment, 16(4), 275-286. DOI: 10.1177/1077559511427178

For more information please contact: [email protected]